Although there are many gaps in its history, few manuscripts can claim such a fascinating and diverse provenance. Assuming that Louis IX (1214–1270) owned the manuscript, it may have passed to his younger brother, Charles of Anjou (1226–1285), who conquered Naples in 1266 and founded the Angevin Dynasty. Sometime after his death, probably in the fourteenth century, Latin captions were added to the manuscript.

CRACOW: The first documented owner, however, was Cardinal Bernard Maciejowski (1548–1608), Bishop of Cracow, who may have acquired the manuscript in Italy while studying for the priesthood or when he went there on behalf of Emperor Sigismund III (r. 1587–1632). He was elevated to cardinal by Pope Clement VIII in early 1604. According to the inscription on fol. 1, “Bernard Maciejowski, Cardinal Priest of the Holy Roman Church, Bishop of Cracow, Duke of Siewierz, and Senator of the Kingdom of Poland with sincere wishes offers this gift to the supreme King of the Persians at Cracow the mother city of the kingdom of Poland on the seventh of September 1604.” (translation by Daniel Weiss). The unnamed monarch would have been Shah ‘Abbas the Great (1571–1629), who became Shah at age sixteen in 1587. In 1598 he moved his capital from Qazvin to Isfahan and created one of the most beautiful cities in the world. The gift was occasioned by Pope Clement VIII’s papal mission to Shah ‘Abbas to secure tolerance toward Christians and to seek help against the Turks, their common enemy. Because it was too dangerous to go by sea, they went by land, stopping in Cracow. When asked for a suitable diplomatic gift, the cardinal offered the Crusader Bible.

ISFAHAN: After a delay due to Pope Clement VIII’s death (March 3, 1605) and that of his successor Leo XI (April 27, 1605), the papal mission returned to Cracow for new presentation letters from Paul V, and finally, after three and one-half years, reached Isfahan on December 2, 1607. The manuscript was formally presented to Shah ‘Abbas on January 3, 1608. Cardinal Maciejowski did not live long enough to receive a thank-you letter, as he died sixteen days later. According to a printed account of the trip, the Shah did convey thanks to the mission and “turned the sacred pages with care and admiration.” Thereafter, he requested one of the missionaries to explain the meaning of the pictures and had the Persian inscriptions added. He also added his seal of ownership on folio 42v, inscribed with the words “Shah in Shah ‘Abbas” (‘Abbas, King of Kings). The versos of the leaves were then foliated in Arabic numerals starting from the back as if it was a Persian manuscript. All forty-eight leaves were then present. Shortly thereafter some leaves depicting the story of Absalom’s rebellion were removed and a new foliation added as well as a note stating there were forty-three leaves.

It has been suggested that the leaves were removed because they might provide an inappropriate model for the Shah’s son, even though the death of Absalom is depicted. On the other hand, Shah ‘Abbas might have removed them in 1615, having expressed great regret and remorse following the execution of his son and crown prince, Mohammud Baqir Mirza, for treason. The Absalom story could have reminded him of his own deed, the result of unwarranted suspicion. After the death of Shah ‘Abbas in 1629, the throne and probably the manuscript passed to his grandson Shah Safi and then to his son Shah ‘Abbas II.

At a later date, perhaps when the Afghans conquered Isfahan in 1722, the royal library and treasury were looted. At some point, the manuscript fell into the hands of a Persian Jew, who had the Judeo-Persian inscriptions added. He apparently knew some of the Old Testament stories better than the Christian cleric who had added the Latin inscriptions, since he corrected them.

CAIRO: The book eventually made its way to Cairo, where it was purchased by John d’Athanasi, a Greek who secured Egyptian antiquities for English collectors, including Lord Amherst of Hackney, whose papyri collections were purchased by John Pierpont Morgan in 1912. Athanasi had the remarkably good fortune of buying the manuscript for three schillings.

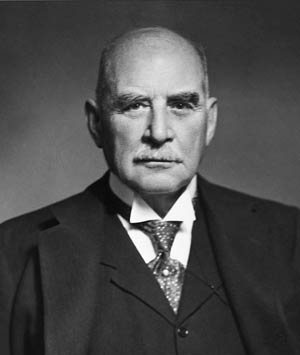

Sir Thomas Phillips, ca. 1860

LONDON: In 1833 Athanasi sold the manuscript at Sotheby’s (March 15, lot 201) in an auction consisting primarily of Egyptian antiquities, such as papyri and splendid mummies. The manuscript brought 255 guineas and was purchased by the London dealers Payne and Foss, who in turn sold it to Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872), the self-proclaimed “perfect vello-maniac.” He bought anything on vellum and assembled some 60,000 manuscripts before his death. He made no plans specifically for the disposition of the collection. Thirlstaine House (Cheltenham) and its contents, including the manuscripts, were left in trust to Katherine (1823–1913), his youngest daughter and wife of Reverend John E. A. Fenwick (1824–1903). His will also gave, after Katherine, a life interest to her third son, Thomas Fitzroy Fenwick (1856–1938), who proved to be a good manager of the collection. Although the will prevented any books from being sold, judicial approval was given, because of financial need, to gradually sell items after 1885.

Once the doors were open, scholars and collectors were admitted. In 1899 Pual Durrieu regarded the Picture Bible as the pearl of the collection. Sotheby’s, on behalf of the Phillipps Trustees, offered the manuscript to Pierpont Morgan on December 14, 1910, for £10,000, saying that £6,000 had been offered by more than one party. It is not known if Morgan or Belle da Costa Greene ever saw the book itself or, understandably, thought the price excessive. It might have made a difference if the book had been associated with Louis IX as Morgan was fascinated by royal provenance and had purchased Louis’s Moralized Bible fragment in 1906. In any case, Morgan died on March 29, 1913, bringing all acquisitions to a halt.

Belle Greene was devastated by the death of her “Big Chief” and the uncertainty it brought for the future. The library and the collections were inherited by his son, John Pierpont Morgan, Jr., (1867–1943), who was not inclined at first, because of World War I, to make additions. But in the end, he decided that the library would continue and that Belle Greene would be retained as librarian. On July 22, 1915, she wrote to Quaritch, the London book firm, that Morgan would allow her to go on collecting after the war.

Belle da Costa Greene in Egyptian Costume. ca. 1910

NEW YORK: On November 21, 1916, although the war was not over, Belle Greene visited Fenwick and daringly bought the manuscript without Morgan’s approval for the same price at which it was offered to Pierpont six years earlier. Fenwick was taken aback when she accepted the asking price without hesitation. According to her friend, Anne Haight, who never finished her biography of Belle Greene, “She examined the manuscript, stuffed it at once into her enormous handbag, saying, ‘I’ll take it, you will receive a check.’” However, either Haight or Greene in relating the incident to her may have captured the spirit rather than the fact of the transaction, for Fenwick wrote to her on December 1, 1916, that the Court of Chancery sanctioned the sale of the manuscript, and that he was now free to turn it over to her representative when payment had been received. Belle Greene herself then wrote to Fenwick on January 3, 1917, that she was pleased that the manuscript had been “released.” She did, however, purchase it on her own initiative, not wanting to lose it a second time. But then she had to inform her boss of what she had done. The letter, dated November 24, three days after her visit to Fenwick, is a model of persuasiveness, making the manuscript seem like an irresistible bargain.

My dear Mr. Morgan,

On my visit to Cheltenham this week I purchased from the present owner, Mr. Fitzroy Fenwick, his famous 13 century French manuscript of the Bible Historiée, the finest example of French art of the period in private hands. It consists alas of only 43 leaves – there are two others in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris (now in course of publication by the Comte de la Borde) and one at Cambridge – for this latter single sheet they paid, several years ago, £300. I agreed to pay Fenwick £10,000 for his 43 leaves. [If one does the math, £300 times forty-three equals £12,900.]

The transaction makes me feel better about my ‘torpedoed ‘ letter of credit as Quaritch offered to try to obtain it for us for £15,000 plus his commission of 5% and Yates Thompson thought I would have to pay much more for it. Mr. Fenwick is coming to London to see me today, when we will arrange terms of payment and talk over 5 other manuscripts. I should like to have, or to have the promise of. If I had been able to stay here several weeks longer I know I could have bought every important manuscript in private hands in England. [Morgan must have been relieved that she was on the next boat home.] There was not time to get to the Duke of Northumberland’s collection (Duveen has just bought his Bellini.) but I may be able to do something by correspondence.

Sincerely, Belle Greene

Jack Morgan

On the same day, Belle Greene received a letter from Sydney Cockerell stating that “the manuscript you were clever enough to secure in Cheltenham is an incomparable treasure and would be cheap at any price. I have long regarded it as the most covetable manuscript of the thirteenth century in private hands.” After she returned to New York she wrote (December 12, 1916) one of her longest letters to Cockerell, regretting she “did not carry you off with me as I did the Fenwick leaves.” Morgan, she said, was “very keen to see the manuscript but quite thoroughly approves of my purchasing it, which is a good omen (for me) for the future.” Morgan also expressed his approval in another way. In 1927 he produced a lavish facsimile of the Picture Bible as his Roxburghe Club obligation and hired Cockerell to do much of the commentary.

The acquisition of the Crusader Bible proved to be an important turning point in the history of the library. It was Morgan’s first great manuscript purchase, one that was followed by many others. In 1919 Belle Greene wrote to Edmund Dring of Quaritch that the present Mr. Morgan “is a continual joy to me as a collector. In his sense of appreciation, discrimination, of rapidly increasing knowledge and sure recognition of the best he will (I fear) soon surpass even his great father. He has a very fine eye and an astonishing memory, and, being a voracious reader, is appallingly knowledgeable. I doubt if there is today another collector his equal, in an all-round way.”

Belle Greene, of course, was hoping that the collections would be preserved through institutionalization, and her hopes were fulfilled when Morgan founded the library in 1924. One suspects that his early purchase of the Crusader Bible played a fundamental role in his vision of the library, to which he continued to make important contributions up to the time of his death. While he only added about 200 manuscripts to the collection, in terms of importance and quality, they certainly matched those of his father, who acquired about 600.