Introduction

In 1999 and 2005, the Morgan Library & Museum acquired the voluminous archives of The Paris Review. Comprising the complete extant editorial, production, and business correspondence, as well as records from over forty years of operation, the archives chronicle one of the liveliest and most respected literary journals of our time. Various materials related to many of the twentieth century's most important writers, particularly postwar Americans, are also among the contents, which span from 1952 to 2003.

A number of authors are represented by correspondence, galley proofs, and other manuscript materials. They include Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges, Paul Bowles, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Truman Capote, T. S. Eliot, Gabriel Garcìa Marquez, Allen Ginsberg, Nadine Gordimer, Ernest Hemingway, John Irving, James Jones, James Laughlin, Doris Lessing, Norman Mailer, David Mamet, Arthur Miller, Toni Morrison, Iris Murdoch, Ezra Pound, Philip Roth, J. D. Salinger, Neil Simon, Susan Sontag, John Steinbeck, Tom Stoppard, William Trevor, John Updike, Wendy Wasserstein, Eudora Welty, Tennessee Williams, and William Carlos Williams, among many others. The collection is housed within the department of Literary and Historical Manuscripts and may be consulted by appointment in the Morgan's Sherman Fairchild Reading Room.

Background on The Paris Review

George Plimpton with writers outside of Café Tournon, Paris, 1950s. Front row, from left: Vilma Howard, Jane Lougee (with Fuki), Muffy Wainhouse, Jean Garrigue. Second row: Christopher Logue, Richard Seaver, Evan Connell, Niccolò Tucci, unidentified, Peter Hyun, Alfred Chester, Austryn Wainhouse. Back row: Eugene Walter, George Plimpton, Michel van der Plas, William Pène du Bois, James Broughton, William Gardner Smith, Harold Witt.

An international literary quarterly, The Paris Review was founded in Paris in 1953 by Peter Matthiessen (1927–2014), Harold L. Humes (1926–1992), and George Plimpton (1927–2003). Dissatisfied with the emphasis on criticism in the literary magazines of the time, Matthiessen and Humes conceived of a new review to feature original works of fiction and poetry rather than “writing about writing.” Matthiessen invited George Plimpton, then a student at Cambridge University, to become editor, a position he held until his death. Subsequent generations of editors have had a hand at editing the magazine as well, lending a vitality rare in a literary undertaking of such longevity.

William Styron, one of the publication's advisory editors, stated the purpose of The Paris Review and defined its editorial policy in a letter in the first issue. “Dear reader,” he wrote,

The Paris Review hopes to emphasize creative work—fiction and poetry—not to the exclusion of criticism, but with the aim in mind of merely removing criticism from the dominating place it holds in most literary magazines and putting it pretty much where it belongs, i.e., somewhere near the back of the book. I think The Paris Review should welcome these people into its pages: the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and non-axegrinders. So long as they're good.

The Paris Review upheld these principles. Jack Kerouac's earliest work was first published in its pages, as were the first stories of Nadine Gordimer, Philip Roth, Gina Berriault, Evan S. Connell, Leonard Michaels, Terry Southern, James Salter, George Steiner, Italo Calvino, Richard Ford, and V. S. Naipaul, and as was the poetry of A. Alvarez, W. S. Merwin, Adrienne Rich, and many others. Jay McInerney, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Rick Bass, and Mona Simpson were all first published by the magazine. Selections from Samuel Beckett's novel Molloy appeared in the fifth issue, his first work published in the United States. The journal also published a number of excerpts from works now widely read, such as William Styron's Confessions of Nat Turner; Philip Roth's Goodbye, Columbus; Ned Rorem's Paris diaries; Peter Matthiessen's Far Tortuga; Donald Barthelme's "Alice;" and Jim Carroll's Basketball Diaries.

As The Paris Review began to attract attention, works by more established writers, such as Jorge Luis Borges, John Updike, Pablo Neruda, Henry Miller, Malcolm Lowry, Allen Ginsberg, Ernest Hemingway, John Hersey, Margaret Atwood, Grace Paley, E. L. Doctorow, Harold Brodkey, William Faulkner, Ezra Pound, and Norman Mailer began to appear alongside those of talented newcomers.

In addition to the focus on creative work, The Paris Review's editors found another alternative to criticism—letting the authors talk about their work. The first issue featured an interview with E. M. Forster, who spoke on the art of fiction, recounting how he first conceived of the classic Marabar Caves sequence in A Passage to India. This was the first in the acclaimed “Writers at Work” series, which now includes over four hundred interviews ranging from Ernest Hemingway (conducted by George Plimpton—perhaps the best known) and William Faulkner to Joseph Brodsky, Gabriel Garcìa Marquez, and Toni Morrison.

Contents of the Archive

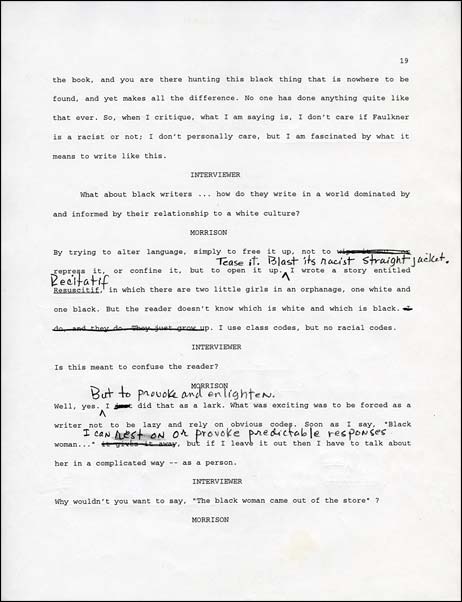

Typed transcript page of Claudia Brodsky Lacour, Elissa Schappell, and George Plimpton interviewing Toni Morrison (1993), with the author's autograph corrections and additions. © 2020 The Paris Review

The archives of The Paris Review contain the following materials. For more information consult the finding aid:

- General editorial correspondence

- Published work (fiction, poetry, interviews, and features); in most cases the publication process can be traced from submission through development, editing, and authorial revision

- Interview manuscripts, correspondence from the interview subjects, author portraits, and galley revisions by the editors, the interviewers, and the subjects interviewed. Also includes some original pages of literary drafts supplied by interview subjects

- Interview correspondence and production notes pertaining to The Paris Review's various book publication projects, including Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, collected in nine volumes, published by Viking Penguin, The Paris Review Anthology, published by W. W. Norton, and, most recently, Women Writers at Work, Beat Writers at Work, and The Writer's Chapbook, all Modern Library publications

- Unpublished editorial material—stories, interviews, and features that were commissioned or submitted but never published in the magazine

- Audiotaped interviews with the authors for the magazine's interview series. These audio interviews have been digitized and are available for research consultation in the Morgan’s Sherman Fairchild Reading Room.

- Miscellaneous memorabilia, including photographs, clippings, and bound notebooks

- Annotated manuscripts from the editorial consideration process

- Layout boards and signatures

- Financial and commercial records

- Forty years of "common books"—bound logs containing telephone messages, memoranda, editorial announcements, minutes, random musings, and office jottings; financial and commercial records; and subscription requests