NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

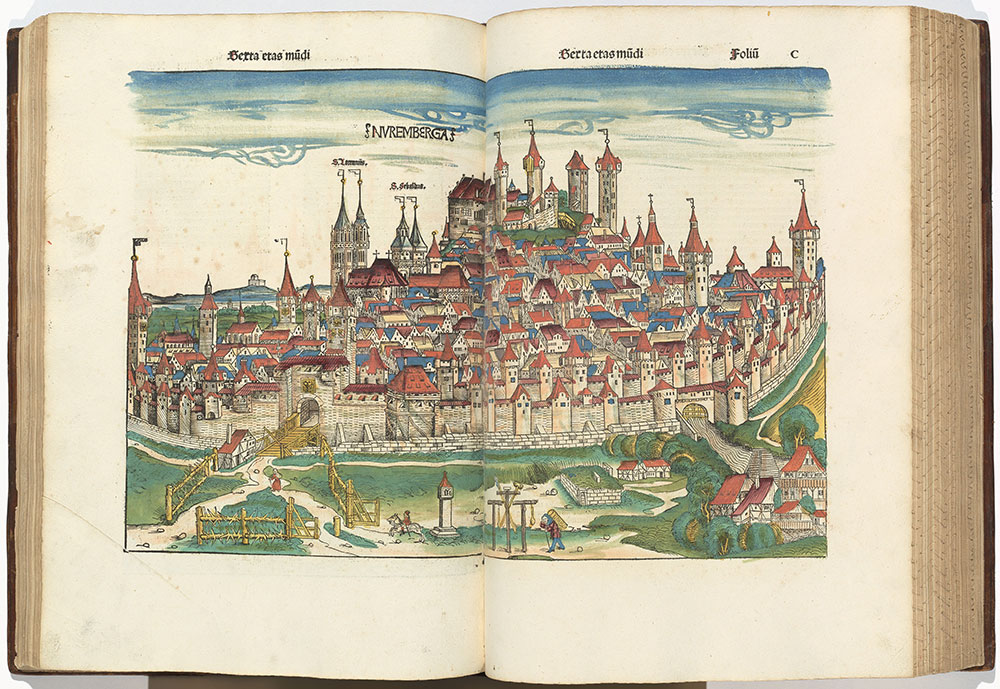

Structured around the seven ages of the world, from Creation to the Last Judgment, the “Nuremberg Chronicle” stands in the long tradition of universal chronicles, many of which also highlight the importance of a specific city. Deliberately placed at the beginning of the sixth age, the Christian era, this view of Nuremberg presents the city as the New Jerusalem. At left are the towers of its most important parish churches: St. Sebald and St. Lawrence. The Women’s Gate occupies the left foreground, with its double-headed eagle identifying Nuremberg as an imperial city. A stele occupies the foreground alongside a group of three crosses. These features, together with the raised platform to the right, where criminals were beheaded, mark the site as a place of execution. Salvation for some presumed punishment for others.

Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514)

Woodcuts by workshop of Michael Wolgemut (1434–1519)

Liber chronicarum (“Nuremberg Chronicle”), in Latin

Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Paul Mellon Collection, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1991.7.1, fols. 99v–100r

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Of the Free Imperial Cities, none is better known than Nuremberg, and no artifact associated with it more famous than the extensively illustrated world history known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, compiled by the physician and Italian-trained humanist Hartmann Schedel. An immensely ambitious work, the Chronicle was commissioned by the Nuremberg merchants Sebald Schreyer and his son-in-law, Sebastian Kammermeister, and published in 1493 by Anton Koberger. The original edition was in Latin, shortly followed by a German translation.

Structured around the seven ages of the world, spanning from Creation to the Last Judgment, the Chronicle stands in the tradition of earlier universal chronicles, many of which were heavily illustrated and also carried world history forward to highlight the importance of a specific city.

Comprising over 1,800 woodcut illustrations, printed from 645 blocks, the Chronicle’s extensive visual program was executed under the supervision of the painter Michael Wolgemut, whose workshop Albrecht Dürer was trained.

Among the Chronicle’s most famous illustrations are the spectacular city views, particularly that of Nuremberg, for which a deliberate effort was made to ensure that the city—originally planned for later in the volume—would be positioned instead toward the beginning of the sixth

age, which starts with the birth of Christ. Nuremberg thus appears as the New Jerusalem.

As was common in the art of the period, the Chronicle’s city views combined precise observation with conventional motifs, both of which contribute to the making of meaning. The view of Nuremberg—the only one that fills a two-page spread to the exclusion of the main text—impresses on account of its selective accuracy. At right center, atop a high bluff at the northern periphery of the city, stands the Burg, or imperial castle, which often hosted visiting German kings and emperors. To the left can be seen the twin towers of the church of St. Lawrence, for which the Geese Book, exhibited nearby, was made.