ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

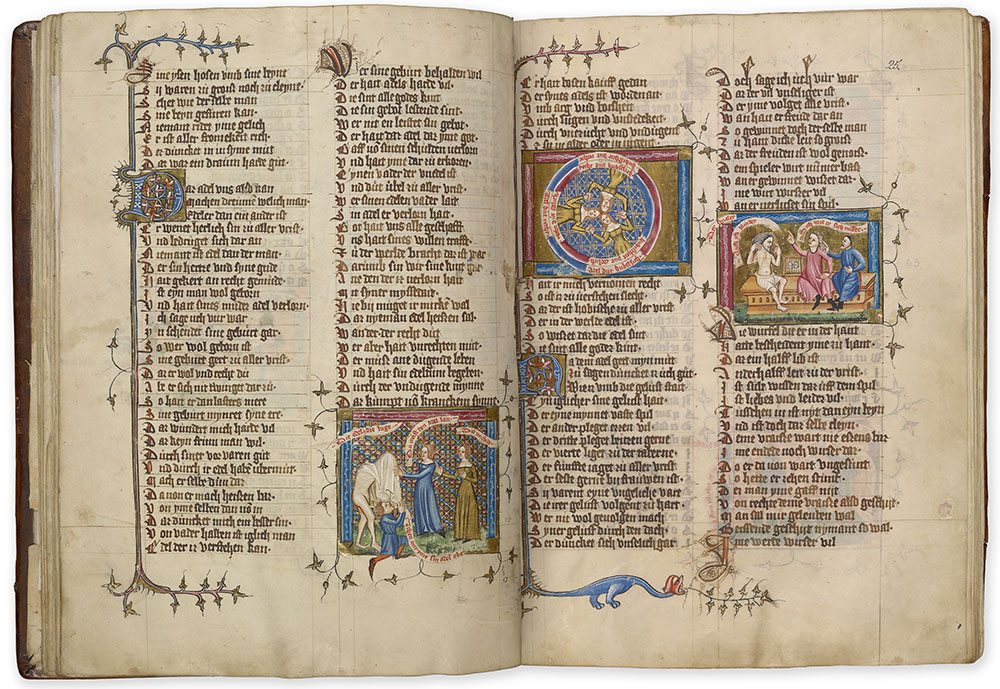

Written around 1215–16, The Italian Guest is the sole surviving poem by Thomasin von Zerclaere, a canon at the court of the German-speaking patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli (northern Italy). The work seeks to educate noblemen in the rules and norms of courtly love, chivalry, ethics, rulership, and good manners. The illustrations constitute a critical part of the work’s didactic program and enhanced its appeal to lay readers. At left, personifications of vices rob a nobleman of his clothing. At right, Justice, Nobility, and Courtliness join hands in a circle; a second miniature shows the winners and loser of backgammon, a critique of gambling. This copy was commissioned by Kuno von Falkenstein (1320–1388), archbishop elector of the imperial city of Trier.

Thomasin von Zerclaere

Der wälsche Gast (The Italian Guest), in German

Germany, Trier, ca. 1380

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.54, fols. 24v–25r

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Aristocratic patronage made its mark on secular illustration, as exemplified by The Italian Guest, a didactic poem written around 1215–16. The sole surviving work of Thomasin von Zerclaere a canon at the court of the German-speaking patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli at the northern end of the Adriatic Sea, it seeks to educate noblemen in the rules and norms of courtly love, chivalry, ethics, rulership, and what we would call good manners. The poem reflects the perceived need to lend the court, which by the thirteenth century had emerged as a cultural center independent of ecclesiastical control, its own ethical rationale. The illustrations, which comprise as many as 125 separate subjects, constitute a critical part of the work’s didactic program and certainly enhanced its appeal to lay readers. This fourteenth-century copy of the work made for Kuno von Falkenstein, the archbishop-elector of the Free Imperial City of Trier, speaks to its crossover appeal to both clerical and aristocratic audiences.

The three miniatures on this opening, indebted in style to contemporary French illumination, focus on the Virtues and Vices. Rather than prefacing sections of the text, the images have been inserted directly into the relevant passages of the narrative, enhancing their immediacy.

The first, on the verso, shows a nobleman robbed of his clothing by personifications of the vices, literally stripping him of his nobility. Kneeling below the unfortunate noble is a personification of Wickedness; to the right stand two women exemplifying Deceit and Inconstancy.

Two miniatures on the facing page represent, respectively, the affinity among Justice, Nobility, and Courtliness—expressed by means of their joining hands in a circle—and, in a scene reminiscent of later genre paintings, the winners and loser of a board game, in this case backgammon, a critique of gambling. Whereas the loser has lost even his clothes and bewails his blindness, his opponents exclaim, “See how he cries out!” Harking back to famous literary heroes, Thomasin asks: “Where are Erec and Gawain, where are Parzival and Iwein? . . . The virtuous people are all hidden away.”