RITE AND RITUAL

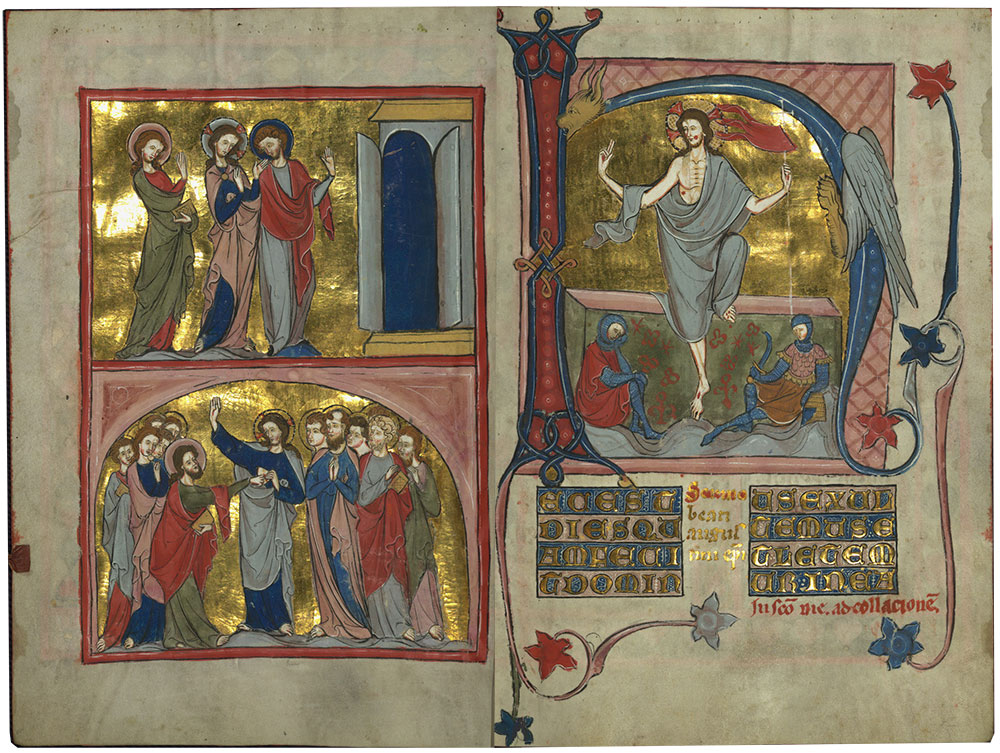

In its profuse use of gold, whether in the burnished backgrounds or the display scripts, this collection of homilies emulates the lavish aesthetic of imperial manuscripts of the early Middle Ages, despite its adoption of Gothic conventions. The homilary—a collection of sermons—was made for and in part by a community of Cistercian nuns. A reform order, the Cistercians traditionally eschewed such luxury, but not here. In its monumentality, the grand initial of the Resurrection rivals that of the full-page miniature on the facing page, which depicts two of Christ’s appearances to the apostles after his Resurrection: Christ as a pilgrim on the road to Emmaus and the Doubting Thomas.

Homilary, in Latin

Germany, Westphalia, ca. 1330

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.148, fols. 45v–46r

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This richly painted book contains a collection of sermons for use during the Easter season. It is part of a pair, of which the other volume—now in Oxford—gathers together sermons for Christmas time.

Both manuscripts were made for a Cistercian convent in Westphalia, a region in northwestern Germany. In the High Middle Ages, the Cistercians were celebrated for their austerity, which led them to reject all forms of luxury, including the visual arts. In this book, however, no trace of such restraint remains.

A team of at least three professional artists painted most of the miniatures. Set against sheets of burnished gold, their elegant, elongated figures reflect the latest developments in painting from France. Shown here, at left, are two scenes that demonstrate Christ’s resurrection: above, is Christ on the Road to Emmaus, where he appears to two apostles who previously thought him dead; below is the Doubting Thomas, who needed physical proof that Christ had risen from the dead, and thus presses his finger into the wound in Christ’s side. At right, filling the oversized initial H, is the Resurrection itself. Two small soldiers are shown sleeping as Christ rises from the tomb. The composition evokes statues of the Resurrection that were a common fixture of Cistercian convents in Westphalia and played an important role in the Easter liturgy, as did this manuscript.

Gold is also used for the display scripts and the massive frames that adorn nearly every page of the manuscript. Several of these text pages were painted by the nuns for whom the manuscript was made. The extravagant use of gold represents just one of a number of archaic features that appear to have been deliberately adopted to evoke the lavish commissions characteristic of imperial female foundations of the earlier Middle Ages.