VIENNA: IMPERIAL RIVALRY AND HABSBURG AMBITION

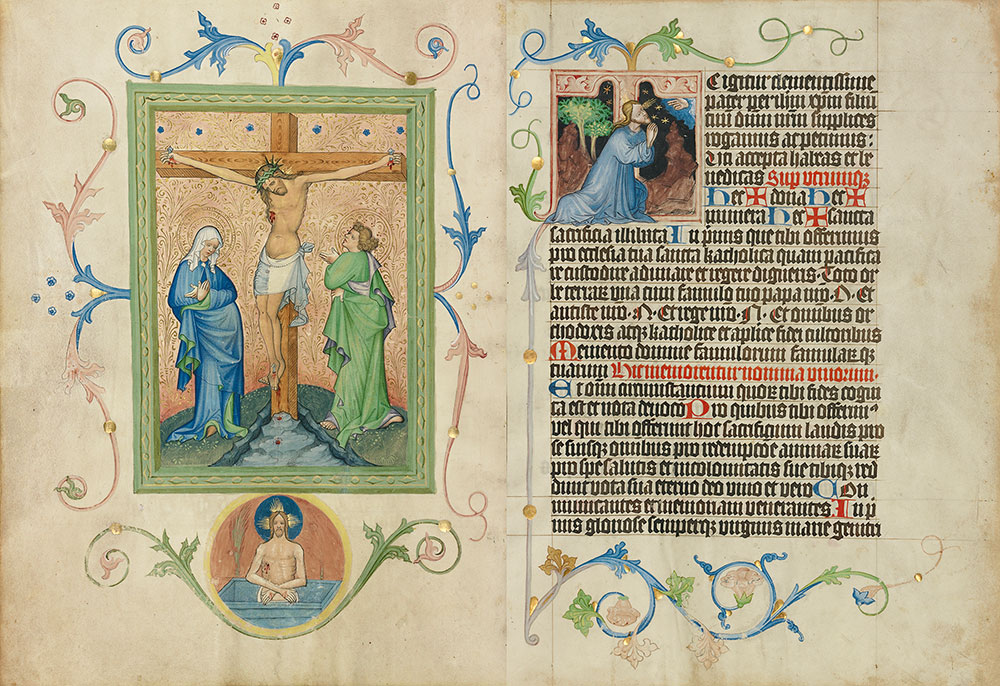

This Mass book may have been commissioned as an imperial gift to the college of theology at the University of Vienna. In the Crucifixion, the figures of Mary and John are elongated and contorted, in dramatic contrast to the placid figure of Christ, whose blood flows copiously from his feet. Below the Crucifixion, a smaller image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows was intended for the priest to kiss during Mass. At right, an initial T marks the beginning of the Eucharistic prayer. The embedded depiction of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane omits any narrative elements, focusing solely on Christ in prayer. The facing miniatures were painted by two different itinerant artists who regularly collaborated on important commissions.

Missal for the Collegium Ducale, in Latin

Illuminated by the Master of the Kremnitz Stadtbuch and Master Michael

Austria, Vienna, ca. 1420–30

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS Ludwig V 6, fols. 147v–148r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

As the seat of Habsburg rule, Vienna became an important artistic center. Its court, which included a powerful patrician class, its churches, and its university all had need for elaborately illuminated manuscripts. Commissioned in the early fifteenth century, this unusually large missal belonged to the Collegium Ducale, the college of theology at the University of Vienna. T

The opening on display stems from two artists. An anonymous craftsman contributed the Crucifixion of the left, whose prominent frame resembles a panel painting. The other artist, known only as Master Michael, painted the scene of the Agony in the Garden in the initial on the facing page. The scene is self-referential in that it provides the priest celebrating mass a model for his own prayer.

Set off by symmetrical acanthus in alternating blue and pink—a hall mark of both Bohemian and Austrian manuscripts of the period—the Crucifixion is paired with an osculatory of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, a small image for the priest to kiss during mass. In the main miniature, the figures of Mary and John are not only elongated and hipshot, but also contorted, in dramatic contrast to the placid figure of Christ. Although John turns his left shoulder to the viewer, his right hand, grasping his garment, occupies the foreground; his left arm, which wraps around his twisting torso, all but disappears, lending still greater emphasis to the almost disembodied hand gesturing toward the body of Christ.

Of the three figures, that of the dead Christ is the most restrained. His loincloth seems about to slip from his partially revealed groin. Christ’s blood flows copiously from his feet, forming not one, but two separate pools, as it drips down from one level of the rocky outcrop to the next. The motif implies that with time the blood will flow out of the image into the chalice on the altar.