This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

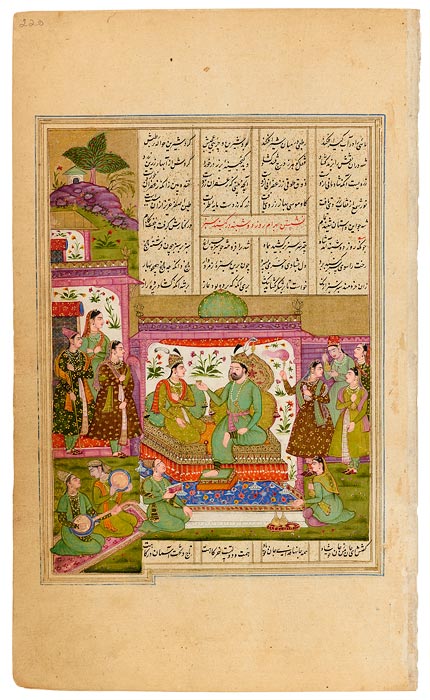

On Monday, the day of the Moon, Bahrām Gūr, dressed in green, asks Nāzpāri for a story.

Good Bāshr, of the country of Rum, loved his books above women but was smitten by a beautiful woman whose face was revealed when a wind lifted her veil. Unable to open his books and forget her, he made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. On the way back, he was joined by evil Malikha, a know-it-all. Not realizing a large vessel with a ceramic rim was a well, Malikha bathed in it and drowned. Bāshr buried him, gathered his valuables, and took them to Malikha's wife. When she lifted her veil, Bāshr recognized the face that had been revealed by the wind. With the wicked husband dead, the good Bāshr joyfully married his widow.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.