Profanity was a common occurrence on cabaret stages in the 1890s. Jehan Rictus and Aristide Bruant were well-known for using what was then euphemistically called the “mot de Cambronne.” That a serious actor uttered a word that sounded like “shit” on the stage of a formal theater was something else altogether. The crowd booed and whistled for around fifteen minutes when Firmin Gémier delivered his first line; another lengthy interruption occurred later in the play when an actor’s hand served as a doorknob. The shouting doubled in volume after Gémier said Jarry’s name at the curtain.

Jarry had published an essay on the theater a few weeks before the premiere to prepare critics for Ubu roi. His radical ideas were summed up in the title: “The Futility of the Theatrical in the Theater.” For Jarry, actors and naturalist sets were the most “hideous and incomprehensible objects” cluttering the stage. He advocated for minimal props, to be moved around by handlers in plain sight. The use of cardboard masks and unnatural voices could transform performers into symbols, almost like letterforms, to express the writer’s ideas. By dispensing with the illusion of reality, a figure on stage could be a “walking abstraction” in service to the creator’s vision.

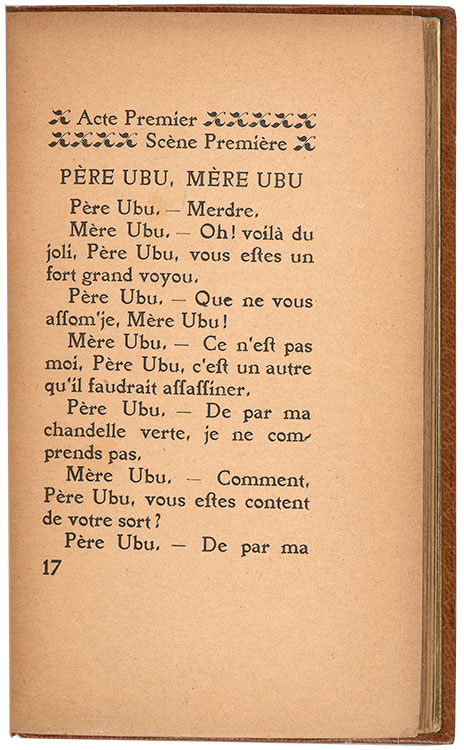

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.