How does a story begin? French author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1900–1944) came to New York in 1940, a few months after Germany invaded France. In 1942, at the height of the Second World War, he crafted a tale about an interstellar traveler in search of friendship and understanding. The bulk of the surviving working manuscript pages and preliminary drawings for The Little Prince are in the Morgan’s collection and presented here. They reveal the stops and starts, decisions and excisions Saint-Exupéry made as he created what has become one of the world’s favorite books.

The manuscript

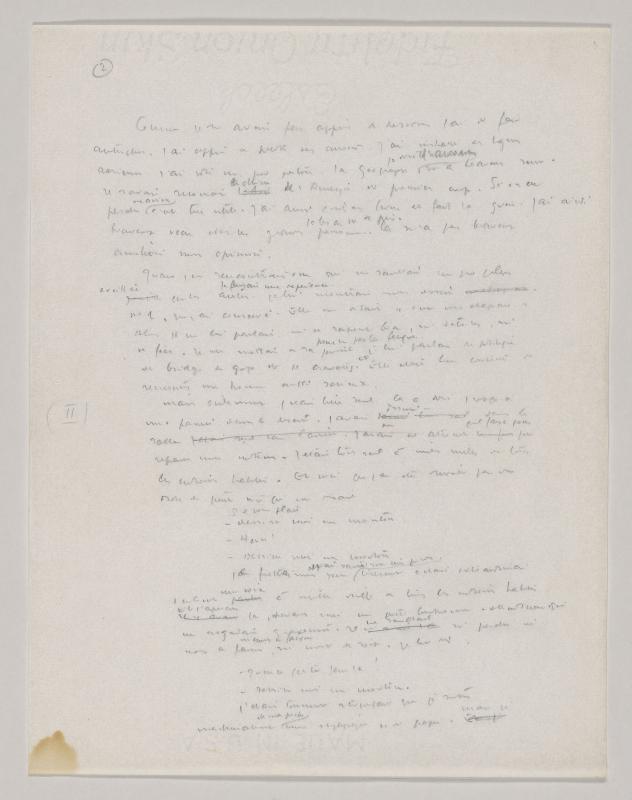

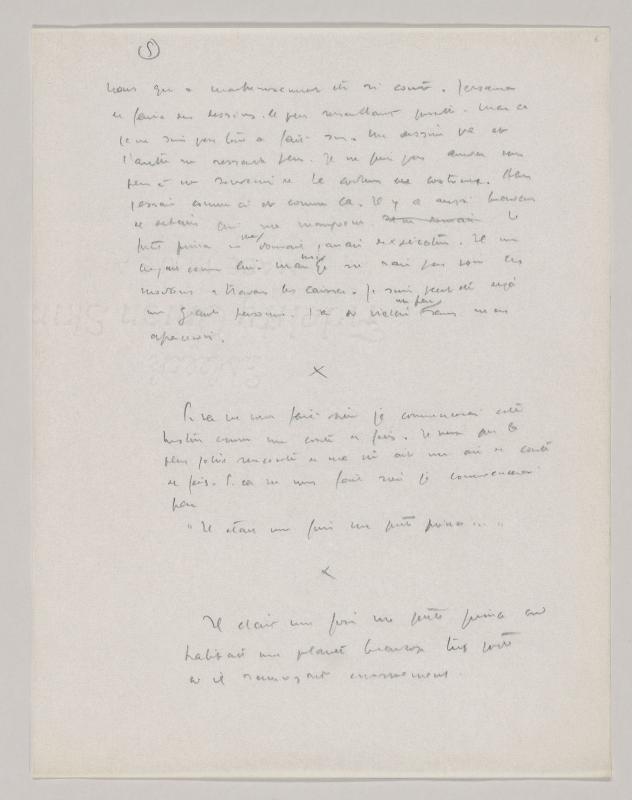

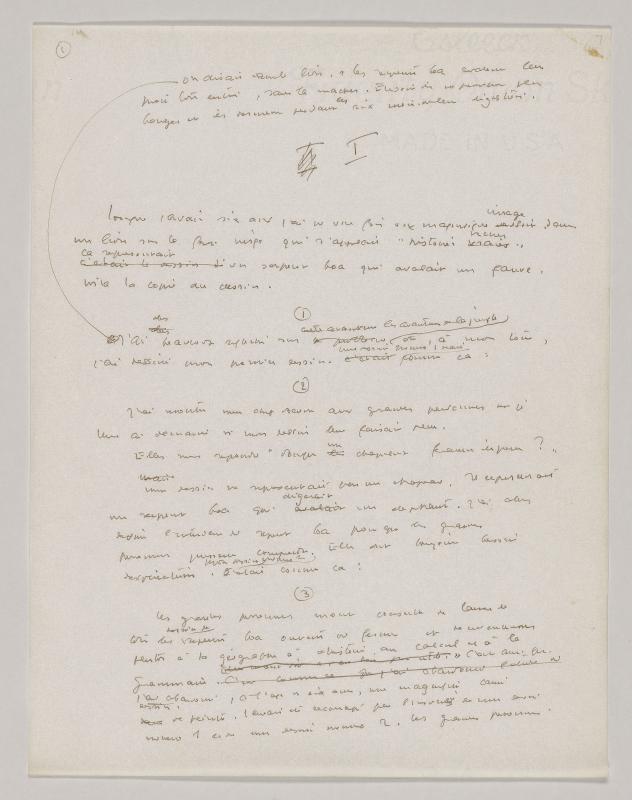

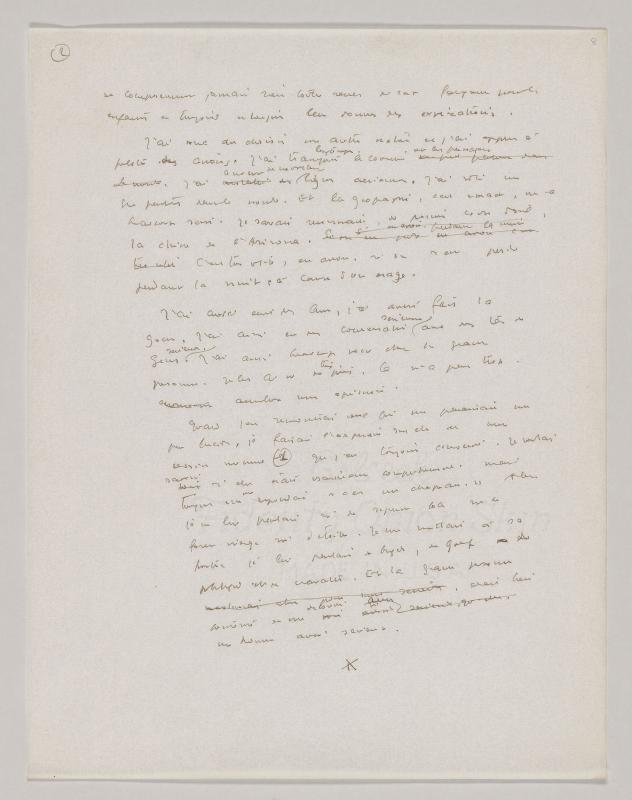

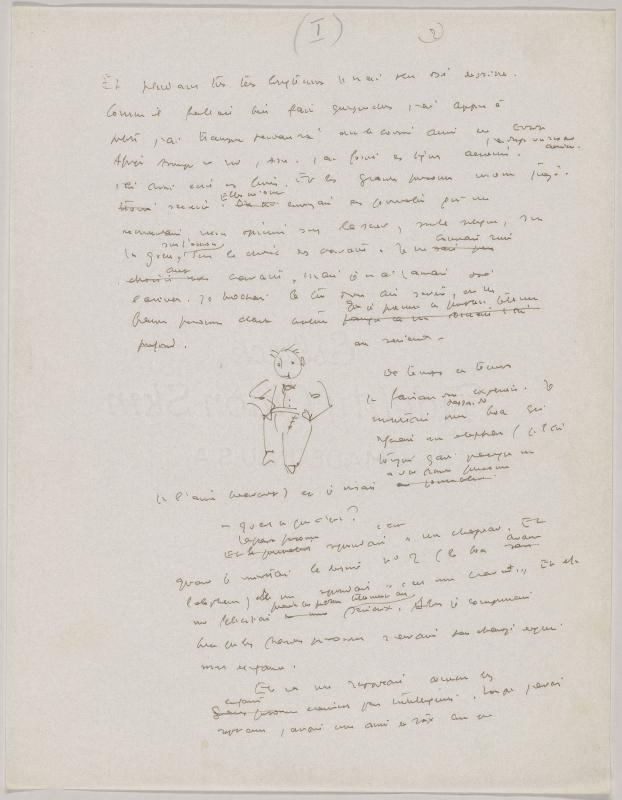

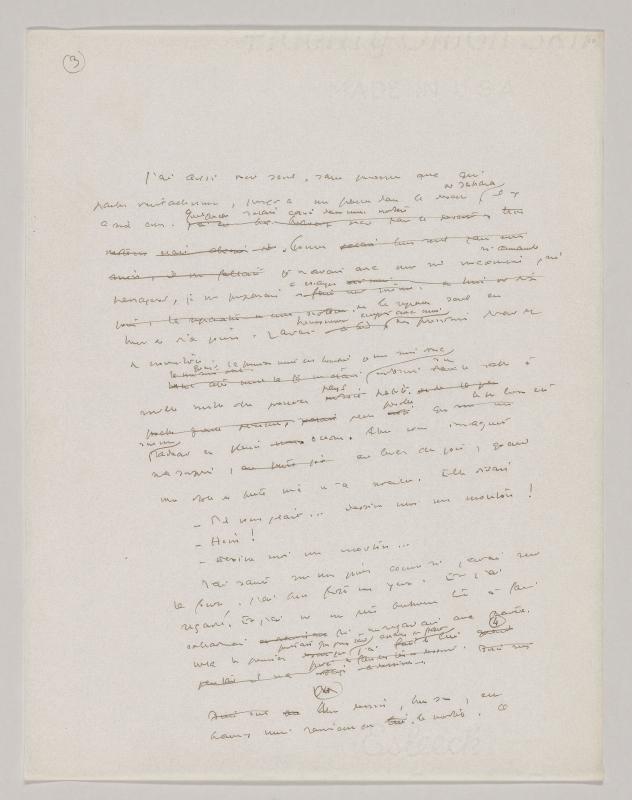

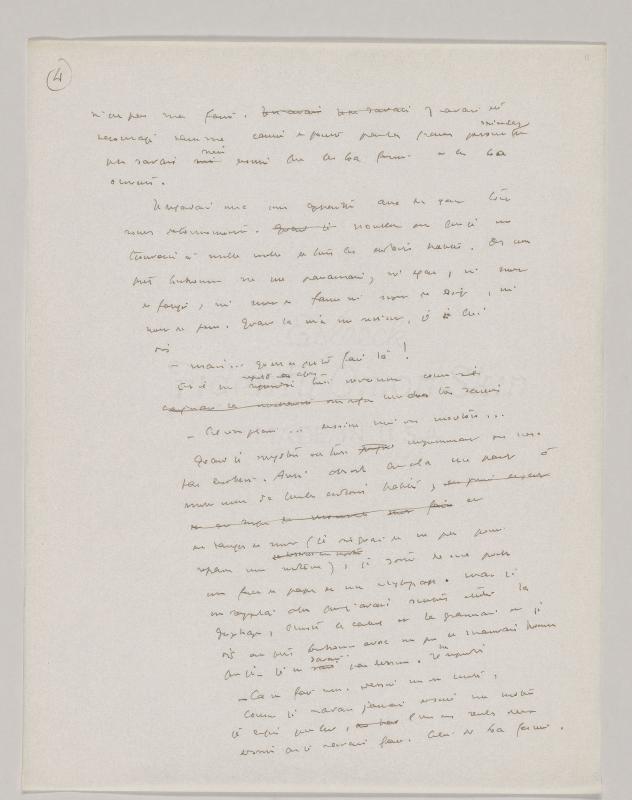

The Morgan manuscript of The Little Prince is an extraordinary physical record of the author’s creative labor. Saint-Exupéry often wrote late into the night, a cigarette in his mouth and a cup of coffee or tea on hand. He thrived on the responses of those he trusted, thinking nothing of calling a friend at two in the morning to read a few pages aloud. He drafted The Little Prince on a thin paper manufactured in western Massachusetts. The watermark, which is visible when the sheets are held up to the light, reads Fidelity Onion Skin. Made in U.S.A.

Saint-Exupéry generally produced multiple drafts of a single chapter, refining dialogue, wording, and tone. But he also deleted entire passages and episodes, paring the text to its essential elements. After completing an early draft, he would sometimes use a Dictaphone (purchased in New York at the extravagant price of $683) to revise orally before entrusting the work to a typist.

The 140-page preliminary manuscript in the Morgan’s collection does not represent the complete record of Saint-Exupéry’s composition of the text of The Little Prince. He discarded some draft pages as he worked, and a handful of preliminary draft pages have made their way into other collections. He made further revisions, not represented in the Morgan drafts, before submitting the text to his publisher.

The foliation of the Morgan manuscript (marked in the upper right corner of each sheet) begins with f. 2; presumably there was once a cover sheet numbered 1, but it does not survive.

The drawings

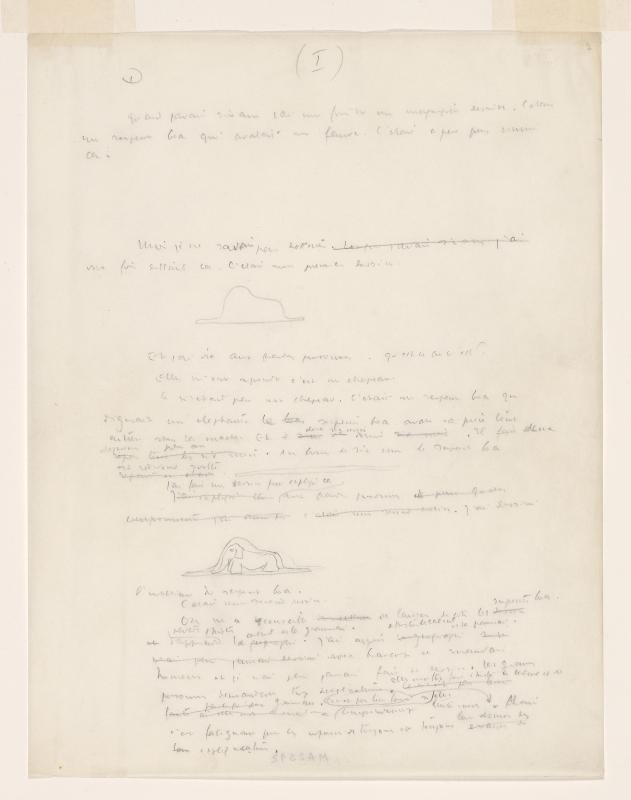

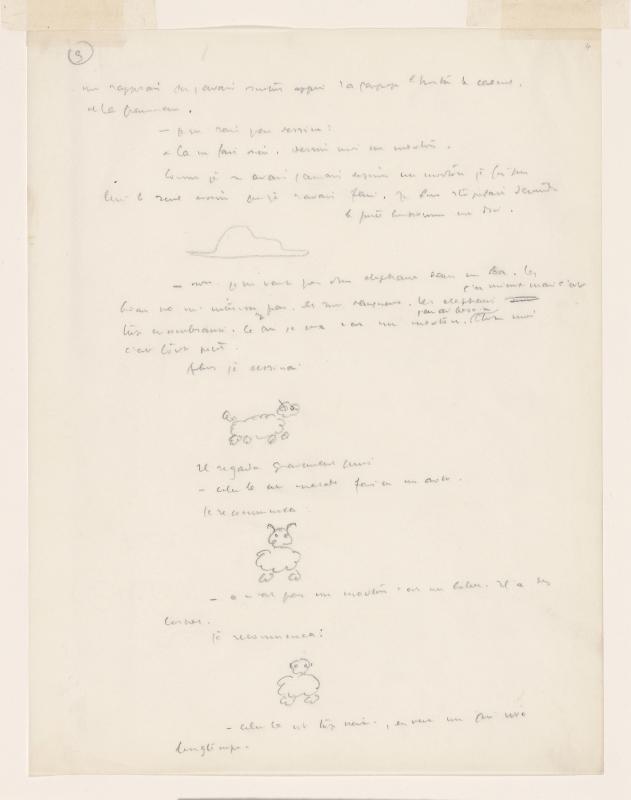

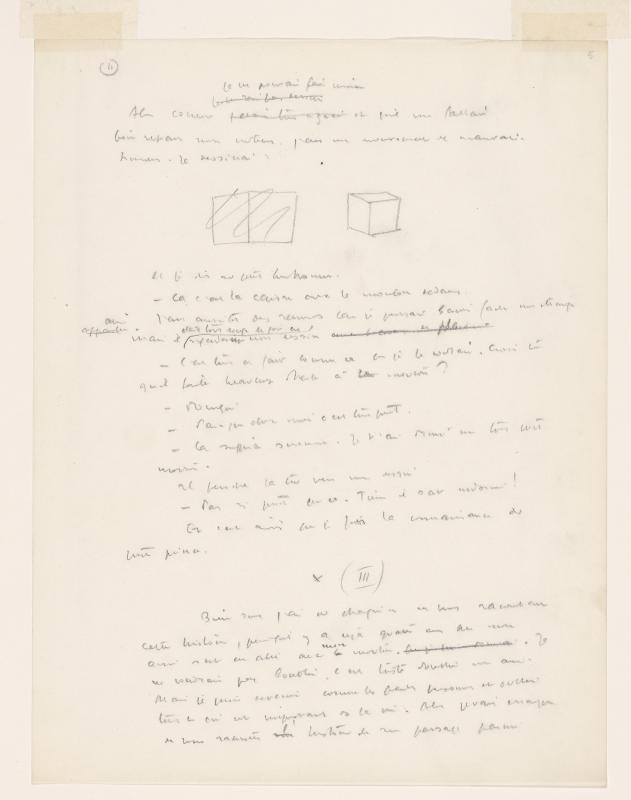

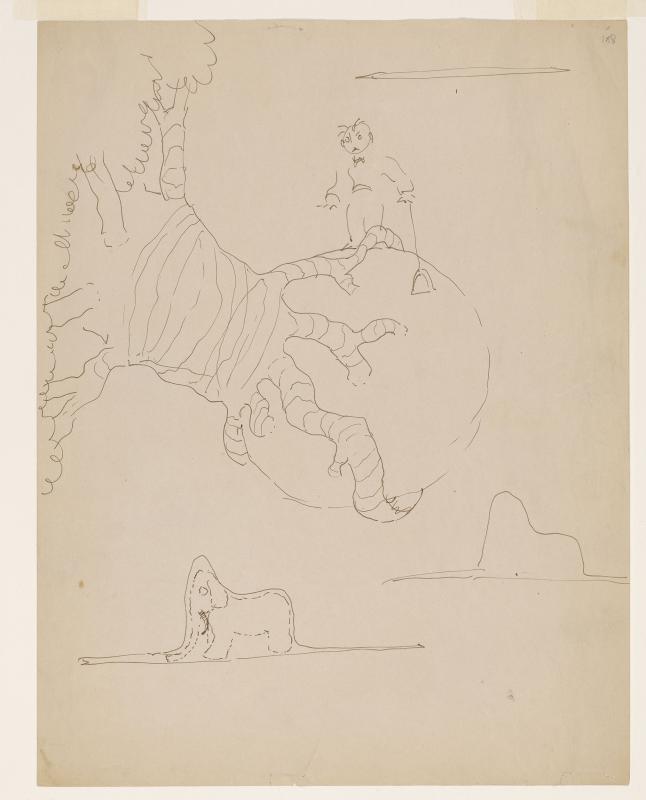

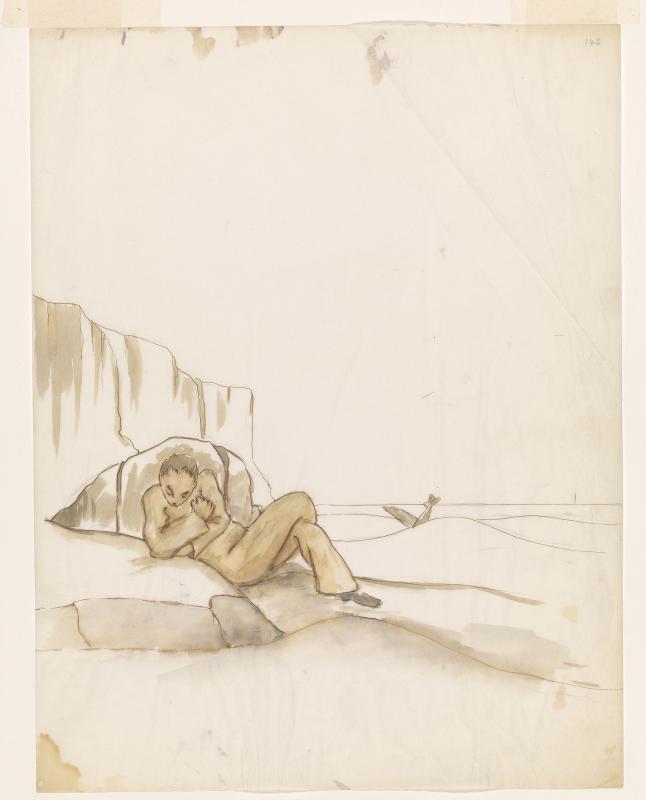

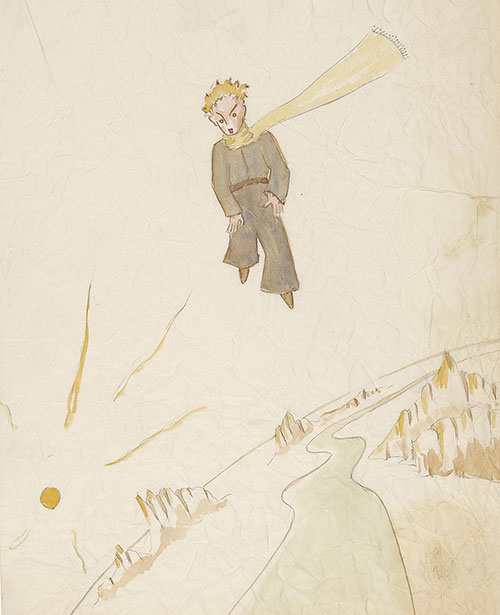

Though Saint-Exupéry had made drawings from the time he was a boy and spent a few unproductive months in architecture school when he was twenty, he had no formal training as an artist and had never illustrated a book before embarking on The Little Prince. He was, however, an inveterate doodler. His American publisher had engaged independent artists for Saint-Exupéry’s earlier titles, but the author chose to illustrate The Little Prince himself. He had been sketching versions of the title character in the margins of letters and manuscripts for quite some time.

The Morgan drawings—mostly ink and watercolor with some pencil—differ dramatically from the published illustrations. Some were excluded from the book altogether; most were substantially reworked; a handful were published with minor revision. In addition to the 35 full-page drawings in the Morgan’s collection, eight pages of the manuscript (p. 2, 4, 5, 9, 19, 41, 140, 141) incorporate sketches.

Publication history

This preliminary draft contract for The Little Prince was drawn up in November 1942, just after Saint-Exupéry had finished writing the story, and went through several revisions before it was finalized in January 1943. The publisher, Reynal & Hitchcock (whose offices were located on Park Avenue near Fifty-Fourth Street), granted the author a $3,000 advance for two books, The Little Prince and a second volume (never completed) about France’s place in the modern world.

The Little Prince was first published in New York, in both English and French, in April 1943. Although Reynal & Hitchcock had published Saint-Exupéry’s earlier books in English, this was the first and only time it issued one of his works in the original French. But World War II had upended the European publishing industry.

The first editions of The Little Prince appeared in near-identical volumes, both priced at $2, though the type of the English-language edition is slightly smaller than that of the French. The translation, made by journalist Katherine Woods, comprises some 17,000 words—3,000 more than the French original. Saint-Exupéry took a strong hand in the layout, stipulating the position, size, and captions for the illustrations.

Just as The Little Prince went into production, Saint-Exupéry learned that he would be redeployed with his old air force squadron, the 2/33 Reconnaissance Group, under Allied command. He took leave of friends and sailed for North Africa carrying a single copy of the newly printed French-language edition. On 31 July 1944, he took off from Corsica on a lone reconnaissance mission over southern France. Like the little prince, who disappeared without a trace from the Sahara, Saint-Exupéry never returned. Just weeks later, Allied troops marched into Paris. The liberation of France was at hand.

The French publisher Gallimard, with offices in German-occupied Paris, would not release its own edition of Le petit prince until 1946. Saint-Exupéry did not live to see his work appear in his native country.

Provenance

Saint-Exupéry wrote much of The Little Prince in a house that he and his wife, Consuelo, had rented on the north shore of Long Island during summer 1942. But he also spent many hours writing at the Upper East Side apartment of his friend and lover Silvia Hamilton (later Reinhardt), with her black poodle as a model for the sheep and a mop-top doll standing in for the title character.

As he prepared to leave the city to return to wartime service, Saint-Exupéry appeared at Hamilton’s door wearing an ill-fitting military uniform. She later recalled that he said, “I’d like to give you something splendid but this is all I have.” He tossed a rumpled paper bag on her entryway table; inside were the manuscript and drawings for The Little Prince. Over the years, Silvia (Hamilton) Reinhardt gave a handful of the sheets to friends and family, but she sold the bulk of Saint-Exupéry’s preliminary manuscript and drawings to the Morgan in 1968.

Credits

Introduction by Christine Nelson, former Drue Heinz Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, 2021. The Morgan is grateful to Stacy Schiff for her scholarship and advice, to Dr. Ruth Kraemer for her scholarly work on the manuscript, and to Olivier d’Agay of the Succession Saint-Exupéry-d’Agay for his longtime support. A published facsimile of the manuscript, with a full transcription of the French, edited by Alban Cerisier and Delphine Lacroix, is available from Gallimard.

This digital facsimile is presented with permission of Gallimard and the Succession Saint-Exupéry-d’Agay for study, enjoyment, and personal or teaching use. To secure publication-quality images, please request permission from the Morgan’s department of Imaging and Rights, and contact the Succession Saint-Exupéry-d’Agay to inquire about intellectual property rights.