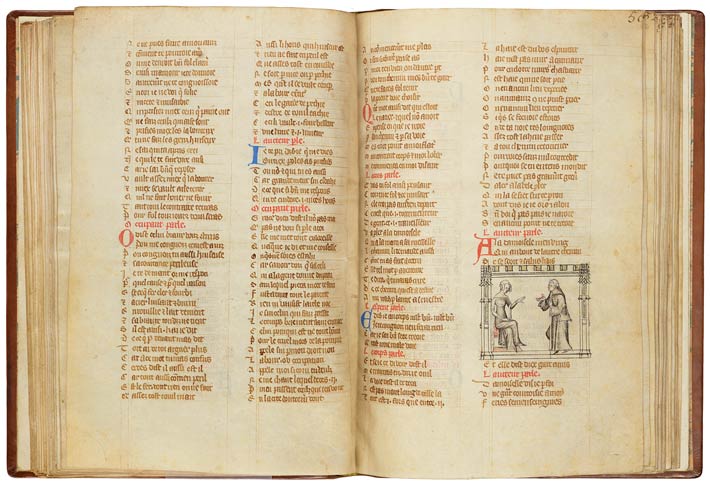

In this allegorical treatise, Idleness is personified as a lazy but beautifully dressed and perfectly coiffed young woman. The tight bodice of her surcot cinches her high, narrow waist, emphasizing the curves of her bosom and belly. Slender tippets fall from her elbows, and the pointed tips of her narrow shoes poke from beneath her hem. A low neckline exposes her neck and the tops of her shoulders, while braided hair frames her face. She gestures condescendingly toward the humble pilgrim, dressed like a monk and equipped with a walking stick and satchel of provisions.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.