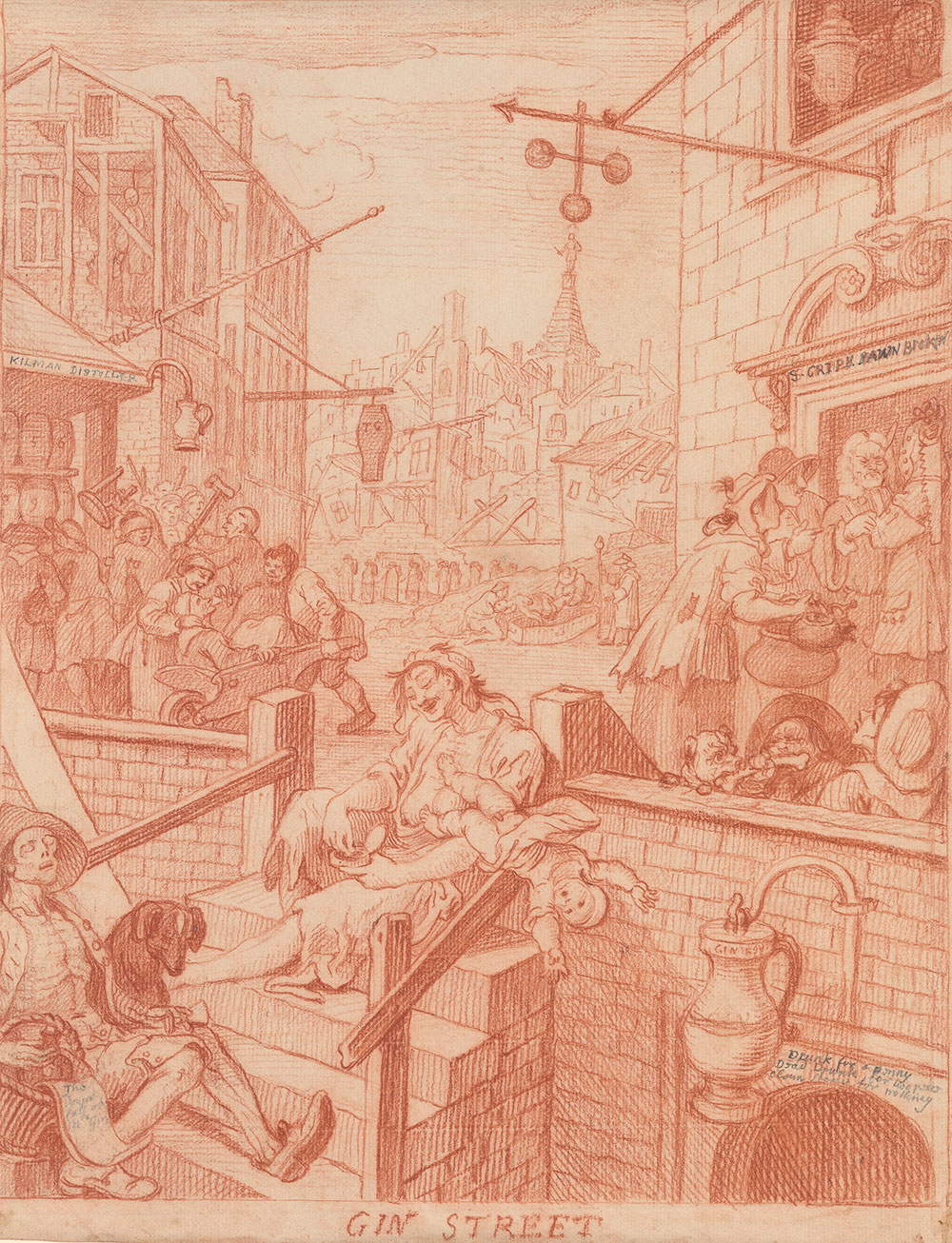

The more alarming events in Gin Lane explore the degradation that went hand in hand with drinking imported gin, a scourge that was thought to target women in particular. At center, a drunken mother seated on stairs above a gin cellar drops her baby as she reaches for a pinch of snuff. Others caught up in the Gin Craze pawn their clothes and kettles to buy the drink, while their fellow Londoners fight dogs for bones or attack each other outside the aptly named Kilman Distillery. At upper left a suicide hangs from the rafters, while a burial takes place beneath a coffin maker’s shop sign. The recognizable setting—with the tower of St. George’s, Bloomsbury, in the distance—is the impoverished and derelict district of St. Giles in Westminster.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Gin Street

1750–51

Red chalk, over traces of black chalk (in left foreground), with graphite, incised with stylus; verso rubbed with red chalk for transfer.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909

The Morgan Library & Museum, III, 36.

Jennifer Tonkovich:

Hello. I'm Jennifer Tonkovich, the Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints here at the Morgan.

The term gin craze refers to a period in the 18th century, from roughly about 1720 until 1760, during which gin had a major social impact in London. Dutch-made gin became widely available around 1700, and as London grew as a city, gin's popularity soared. In response to the moral panic brought about by such widespread consumption, and its effects, several gin acts were passed to govern the distillation and distribution of gin, beginning in 1729.

Not long after Hogarth published his prints, Beer Street and Gin Lane, his friend, the novelist and magistrate, Henry Fielding, published his inquiry into the causes of the late increase in robbers linking the rise in crime to the consumption of gin. Shortly thereafter, parliament passed the Gin Act of 1751, which did indeed reduce the amount of gin sales in London.

The public effects of gin drinking were dramatic and Hogarth seized on examples with contemporary relevance. For instance, the mother jettisoning her infant as she grabs a pinch of snuff, would've reminded viewers of the scandal of Judith Dufour, who, in 1734, strangled her two-year-old daughter, and sold the clothes she wore to buy gin. In Beer Street, the scene is much more jovial, although when Hogarth completed the print, which he had revised a few times, it had become much rowdier and bawdier, but still less dire than the scene on Gin Street.

The gin craze finally began to wane by the 1760s after legislation cracked down on the number of suppliers and a grain crisis led to a brief ban on distilling. Hogarth's images, however, have remained iconic representations of the anxiety generated by alcohol consumption.