Would it match your idea of the hard-eyed, beetle-browed, iron-jawed financial ogre of the comic supplement cartoonist to be told that one of the strongest personal traits of the man is …that he is absurdly fond of small dogs…

(New York Times, April 14, 1912)

A pair of mythical beings, “Titan” and “Lion Dog,” offers an apt entry point to explore the connection between J. P. Morgan and his favorite Pekingese dog, Shun.1 The great financier’s legendary accomplishments frequently inspire outsized adjectives, and the fabled origins of the diminutive Pekingese conferred a mystical aura. While Morgan’s attachment to Shun garnered scant mention among the notable deeds and exploits of the banker’s well-chronicled life, little things can illuminate larger themes. Morgan’s enthusiasm for Pekingese suggests aspects of his character and taste. In 1900, admiration of Pekingese dogs signaled awareness and appreciation of a narrowly constructed view of Chinese culture. As a banker, Morgan viewed China as a risk with commercial potential. As a collector of antique porcelain, Morgan respected China as a vaunted ancient civilization. As an owner and breeder of Pekingese dogs, Morgan displayed not only a tender side to his more famously exacting nature, but also adherence to the numerous misconceptions that constituted popular understanding of Chinese culture in the West. A brief exploration of the history and distinctive characteristics of Pekingese, the facts and fantasy, will give insight into the Gilded Age interpretation of Chinese culture that shaped Morgan’s predilection for the diminutive dog.

PEKES IN CHINA

Attributed to Zhou Fang, Ladies Wearing Flowers in Their Hair, (detail) c. late eighth–early ninth century, handscroll, ink and color on silk, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang province, China.

Since the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), small dogs, periodically, were coveted playthings of the Chinese elite. Contrary to the mythology built up around Pekingese dogs by nineteenth century Europeans and Americans, the custom of owning toy-sized dogs was neither constant nor exclusively imperial. Dogs, useful for hunting and scavenging, were not universally admired in Chinese culture. Miniature dogs bred to serve as mere playful companions for elegant ladies were an accessory available only to the very wealthy.

While the dog has been honored by the Chinese as one of twelve animals in the Chinese zodiac and admired for its industry and loyalty, it also carried negative connotations, particularly among Han Chinese. Historically, dogs enjoyed higher status among the nomadic tribes along China’s northern and western borders. In written language, the dog radical has been used by Han Chinese since the fourth century for words to connote something foreign and of a savage or barbaric nature.2 When the Manchus conquered the Han in 1644, the lowly station of dogs improved. Dog, a dish enjoyed by the preceding Ming court, was removed from the imperial menu.The ban on eating dog meat stemmed from Manchu hunting culture and the belief that a dog provided critical aid to Nurhaci (1559–1626), the esteemed Jurchen leader who united the tribes and initiated the attack on the Ming.3 The Manchu tradition of valuing dogs extended beyond large mastiffs and hunting hounds to a type of small dog. During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the tiny. short-legged, short-snouted happa dogs, originally used for scavenging and ratting, were repurposed and miniaturized to serve as living toys for elite women—compact accessories that could be carried within the sleeve of a silk robe.4

Bred to look like miniature lions, the dogs served a dual role of guardian and companion. In China, as in the West, the lion symbolizes power, loyalty, and strength, but also carries spiritual significance as a guardian of Buddhist teachings. For centuries stone and metal pairs of lions were placed at temple and imperial palace entryways as guardians of the liminal space between secular and spiritual realms. By the twelfth century, the lions were depicted as male, with a paw atop a beribboned ball, and female (yet still physically a male), with a paw resting on a small cub. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the lions, still muscular and assertive, became more dog-like. By the mid-Qing dynasty, the figures, transformed to mythical creatures known as Buddhist Dogs or Foo dogs, are floppy-eared and playful. The aggregate prestige of Buddhism and Empire emblemized by the lion-dog served as impetus to breed pocket-sized embodiments of privilege and power.

“The Empress Dowager Cixi surrounded by attendants in front of Renshoudian, Summer Palace, Beijing” Hai Lung or Sea Otter in the foreground, ca. 1900, Photograph Free Gallery of Art Archives, Washington D.C. FSA A.13 SC-GR-275.

The most influential advocate for the Pekingese was the Empress Dowager Cixi who ruled as regent from 1861 to1908. Some twenty dogs were housed in the imperial kennels, which she visited frequently to cast a critical eye on the merits and flaws of each animal.5 Her favorite, named Sea Otter, is described by Yü Der Ling, one of ladies-in-waiting.

His name was Hai Lung, sea otter, because he so much resembled one of those animals. He was a Pekingese pug, dark brown, with long silky hair…. He was probably the best pedigreed dog; in the Middle Kingdom, and Her Majesty adored the little brute…. His harness was of red- silk-covered leather, and under his neck were three bells, two small ones and one, the central one, somewhat larger…. One always knew when the dog;-eunuch took his charge anywhere. When it trotted the bells could be heard for some distance.6

PEKES IN THE WEST

A crime of opportunity instigated the first appearance of the small, silken-haired dogs in Europe. In October 1860, Lord Elgin (1811–1863), acting on behalf of the British Empire to avenge the imprisonment and torture of thirty-nine British, Indian, and French soldiers, staged a stark display of martial dominance by ordering the destruction of Yuanmingyuan, an eighteenth-century, European-style, imperial complex of palaces not far from Beijing. Wholesale looting of art, jewels, robes, furs, weapons, and furnishings occurred before the buildings were burned to rubble and ash. During the ransacking a few British soldiers encountered some tiny dogs. A portrayal of the event, available on the American Kennel Club website, makes a vivid impression.

Amid the jade carvings and bronze statues at the Old Summer Palace, as the royal compound was called, the military men stumbled across living treasures–five Pekingese that somehow hadn’t been killed to keep them out of foreign hands when the emperor and his family fled. The dogs were found in an apartment belonging to the emperor’s aunt, who had committed suicide as the military forces approached.7

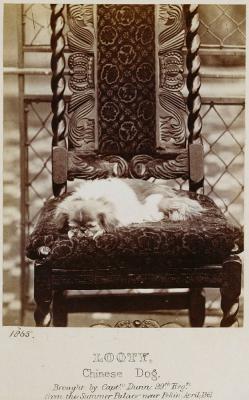

William Bambridge (1810–1879) Looty the Pekingese 1865. Albumen print. Royal Collection Trust, London, RCIN 2105644.

The term “living treasures” simultaneously highlights the elevated status of the dogs and identifies them as imperial plunder. The paragraph infuses dramatic tension into the scene by mentioning the unsubstantiated yet often-repeated suicide of an imperial family member. The five dogs from Yuanmingyuan, along with thousands of artifacts, sailed to England. The two dogs taken by a naval officer, Sir George Fitzroy, were given to his cousin, the Duchess of Richmond. Admiral Lord John Hay kept a pair, and the fifth dog, carted off by General (then lieutenant) Dunne was presented to Queen Victoria who brazenly named it Looty.

The exotic nature of the new breed was reinforced by the Western name “Pekingese,” which locates it to China’s imperial city. The oriental “otherness” was subsequently amplified by the pseudo-Chinese names often given to the dogs by their British and American owners. Names such as Ah Cum or Mee Foo lent an air of authenticity. Chinese-style names merged with English names such as Tsang of Downshire or Goodwood Lo enhanced lineage. The five Yuanmingyuan dogs could not mate fast enough to satisfy growing demand for the “little lions.” In the 1880s and 90s, diplomats and officers were pressed by leading ladies of English society to secure more Pekingese in order to improve the breed in England—an ironic fact about which the scholar Sarah Cheung aptly observes, “that the real contribution of the Summer Palace five may well have been more mythical than material.”8 While the deeds of Yuanmingyuan loomed large, it was the Empress Dowager Cixi who deserves the lion’s share of credit for popularizing the breed in the West. Her passion for the animals and habit of gifting Pekingese from the imperial kennels to favored courtiers and illustrious foreign visitors assured notoriety. British and Americans, granted a visit to her court or honored with the gift of a puppy, tended to relate these encounters in glowing terms, often embellishing the truth. For instance, the most famous guide for the appearance and care of Pekingese, “Pearls Dropped from the Lips of Her Imperial Majesty Tzu Hsi Dowager Empress of the Flowery Land” reputedly in the possession of the Pekingese Club, London, first appeared in a pamphlet by Mrs. Ashton Cross.9 This unprovenanced document, supposedly written by Cixi, advised that the dogs dine on “shark’s fins” and “curlews’ livers,” and be trained to bite “foreign devils,” observe the Confucian principle of “venerating ancestors,” and insisted that the ears should be “sails set like a War Junk.”10 The florid, fanciful language, embedded with menacing foreign references, mimics Chinese writing style. Attributing authorship to the empress dowager effectively established a direct link between the dogs, their owners, and the Chinese imperial court.

In 1905, one of the more notable American visitors to the imperial palace in Beijing, Alice Roosevelt, was presented by the empress dowager with a black Pekingese named Manchu. Another famous American frequently mentioned as recipient of a dog from Cixi is J. P. Morgan, but there seems to be no evidence to support this claim.11 Despite a youthful fancy, Morgan never traveled to China and, to date, there is no documentation of direct contact between the empress dowager and Morgan.12 There is, however, ample evidence that by 1900 Morgan, along with other members of his family, were proud owners of several Pekingese.

PEKES AND MORGAN

Morgan’s introduction to Pekingese most likely occurred shortly before 1900 in England where the dogs, famed for their exotic, mythical, and imperial pedigree, would have appealed to Morgan as both a dog lover and a collector. It was reported that Morgan was given a Pekingese by Lady Algernon Gordon-Lennox. Lady Gordon-Lennox13 was the daughter-in-law of the Duchess of Richmond, the recipient of two of the original five dogs taken from Yuanmingyuan. Pekingese from Gordon-Lennox boasted an impeccable imperial pedigree. The connection to Gordon-Lennox, and her famed Goodwood strain of Pekingese, establishes at least an indirect link between Morgan and the Qing imperial court that may have been sufficient to fuel the rumored gift from Cixi. Morgan, who was irresistibly drawn to rare, beautiful things, would naturally have been among the first of American elite society to own Pekingese. In 1900, although the breed was not officially recognized, dogs boasting the finest imperial pedigree were exorbitantly expensive. By 1913, at the height of their popularity in the West, Pekingese competed for prizes in the top shows, and the names of the dogs and their owners took up ten pages of the 1913 American Kennel Stud Book.14 A 1912 article in The New York Times relays Morgan’s fondness for his Pekingese.

It is not an uncommon sight in England to discover the Great Man of Wall Street riding about in his motor car with a tiny Pekingese spaniel in his lap, or walking about the grounds of Dover House, his big suburban estate out Putney way from London, with the same dog tucked under his arm. This is "Sing," the successor of a Pekingese given him by Lady Gordon-Lenox some years ago. The original "Sing" was the beginning of a whole brood of tiny dogs now kept at Dover House. This little fellow became the inseparable companion of his master, even being privileged to a lap-seat at quiet dinners.15

It is tempting to speculate that Shun was the “original Sing,” the first of Morgan’s Pekingese and the one gifted to him by Lady Gordon-Lennox. Morgan esteemed objects that were unique au monde.16 A fashionable gift from a notable member of the British aristocracy would have been gratifying and enhanced by its distinguished, exotic origins. Shun was a “living treasure," a Pekingese whose bloodline could be traced back to the imperial dogs from Yuanmingyuan, an exclusive group that included Queen Victoria’s Looty. The prestige alone might have been sufficient to give Shun a special place in Morgan’s affections. It is apparent from family photographs that Morgan was extremely fond of Shun, who accompanied the banker on his extensive travels.

As in other aspects of his life, once affected by an idea or thing, Morgan’s advocacy was all-out. In 1904, the Pekin Palace Dog Association of Britain (later the Pekingese Club) was founded with Lady Gordon-Lennox as its President and J. P. Morgan serving as Vice Chairman. In 1909, the Pekingese Club of America was established with Mrs. Morris Mandy as President and J. P. Morgan in the role of Honorary President. Its first show was held in 1911 at the ballroom of the Plaza Hotel, “suitably decorated with Chinese silks and bronze Foo dogs,”17 with Morgan in attendance for the presentation of the Pierpont Morgan cup, a trophy still awarded today.

Morgan’s naturally competitive spirit extended to his animals, and at least one of his Pekingese, Sing, was a prize winner. Two medals awarded to Sing are retained in the Morgan Library Collection and eloquently convey the persistent effort to communicate the exoticism of Pekingese. Both feature the Chinese mythological male lion-dog in its assertive stance with one paw atop a ball, symbolizing both playfulness and dominance. The design of the medals, a compelling cultural compression, may be interpreted as mediators navigating a tense period of growing disenchantment between China and the West.

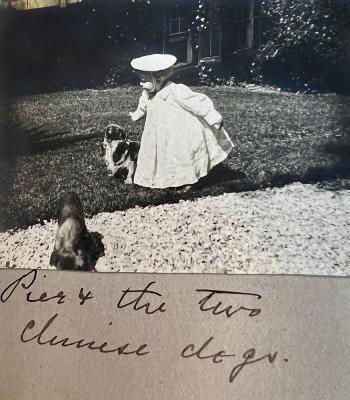

Morgan’s enthusiasm for Pekingese spread quickly to other family members, especially his daughters, Louisa and Anne, and daughter-in-law, Jane. Numerous photographs from the Morgan Library archives affirm the family connection to Pekingese.

CONCLUSION

The end of the nineteenth century witnessed the decline of the Chinese imperial system, a shift significantly hastened by Western imperialism. J. P. Morgan was the indisputable embodiment of the Western confidence and determination required in the high-stakes competition for global economic dominance. In the fast-paced Gilded Age, China, as a waning power, was expediently relegated to the realm of nostalgia, reframed as a cultural concept admired for the splendor and excess of its imperial past. The foregrounding of the sumptuous brilliance of imperial China, as emblemized by Pekingese, allowed Western powers to safely bask in its afterglow without having to linger over present tensions. Morgan’s engagement with Chinese culture through money, art, and his beloved Shun, reflects the values of the period. The scale on which Morgan invested, collected, and, in the case of his living emblems of China, nurtured, was virtually unprecedented. His championing of Pekingese was all the more noteworthy when considering the gender issue. As Sarah Cheang observes, “Early twentieth-century Pekingese (peke) dog breeding, showing, and mythologizing in Britain was a resolutely feminine, upper-class, and “Chinese” affair.”18

J. P. Morgan seated aboard his yacht, the Corsair. The Pekingese in his lap being admired. Photograph. Archives of the Pierpont Morgan Library, ARC1451.

Society women took charge of the clubs, societies, and periodicals dedicated to Pekingese. High-profile figures such as Lady Gordon-Lennox, Alice Roosevelt, Edith Wharton, and Elsie de Wolfe appeared with their dogs on the pages of fashionable magazines and newspapers, bolstering the lofty status of both the Pekingese and their owners. Morgan’s unabashed admiration for Pekingese, within a mostly feminine sphere, evinces his confidence in his opinions and his ease with fame. Morgan's legendary status, particularly in his final decades, afforded him the freedom to declare his affection for Pekes without repercussion. The man who could shape markets with a whisper, played a titanic role in promoting the Pekingese, and all the legend and lore that it entailed, as a most desirable companion.

Cynthia Volk

Independent Scholar and Senior Consultant, Chinese Works of Art, Sotheby's New York

ENDNOTES

- Jean Strouse, Morgan, American Financier (New York: Random House, 1999), 1129.

- Claire Huot, “The Dog-Eared Dictionary: Human-Animal Alliance in Chinese Civilization.” The Journal of Asian Studies74, no. 3 (2015), 604.

- Evelyn S. Rawski, The Last Emperors (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 47.

- Claire Huot, “The Dog-Eared Dictionary: Human-Animal Alliance in Chinese Civilization.” The Journal of Asian Studies 74, no. 3 (2015), 603.

- Princess Der Ling, Imperial Incense (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1934), 182–187.

- Princess Der Ling, Imperial Incense (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1934), 83.

- Denise Flaim, “Pekingese History: Lost Legends of the Imperial Breed,” American Kennel Club, (blog), June 01, 2020.

- Sarah Cheang, “Women, Pets, and Imperialism: The British Pekingese Dog and Nostalgia for Old China.” Journal of British Studies 45, no. 2 (2006), 365.

- Sarah Cheang, “Women, Pets, and Imperialism: The British Pekingese Dog and Nostalgia for Old China.” Journal of British Studies 45, no. 2 (2006), 372.

- Sarah Cheang, “Women, Pets, and Imperialism: The British Pekingese Dog and Nostalgia for Old China.” Journal of British Studies 45, no. 2 (2006), 371.

- Dorothy Quigley, The Quigley Book of the Pekingese (New York: Howell Book House, 1964), 11. Quigley’s book is often mentioned in regard to the claim, but the author does not cite a source.

- Jean Strouse, Morgan, American Financier (New York: Random House, 1999), 161.

- “J. Pierpont Morgan will be 75 Years Old this Week,” New York Times, April 14, 1912.

- American Kennel Stud Book, vol. XXX, (New York:1913), 395–404.

- “J. Pierpont Morgan will be 75 Years Old this Week,” New York Times, April 14, 1912.

- Jean Strouse, Morgan, American Financier (New York: Random House, 1999), 1129.

- Dorothy Quigley, The Quigley Book of the Pekingese (New York: Howell Book House, 1964), 11.

- Sarah Cheang “Women, Pets, and Imperialism: The British Pekingese Dog and Nostalgia for Old China.” Journal of British Studies 45, no. 2 (2006), 360.