Over six hundred drawings by Rick Barton were contained within one document box at the time of my visit to UCLA Library Special Collections on October 18, 2018. The collection has since been fully inventoried and rehoused. Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

In early 2018, I received the welcome news that UCLA Library Special Collections would consider lending drawings by Rick Barton to an exhibition at the Morgan. Moreover, more than 600 drawings that had not been located at the time of my visit were now available to view. My next opportunity to travel to Los Angeles would not arrive until October of that year. But in the interim, I made a number of crucial discoveries.

In the first and second parts of this serial, I discussed an online text (now removed) by Dave Archer. In his 2002 memoir, Archer recounted in remarkable detail his tumultuous relationship with Barton, including stories Barton told him about his life. Barton was active primarily in San Francisco, but he had been born and raised in New York City. He was a veteran and claimed to have spent time in China, where he became enamored of traditional ink painting. Archer shared more with me in a long phone conversation shortly after I returned from Los Angeles, including the detail that after their relationship had ended, Barton relocated to San Diego. Knowing Barton’s place of birth and possible death, as well as the fact that he was a veteran, I was able to gather vital statistics from various indices on Ancestry.com. Richard William Barton was born on May 13, 1928, in Manhattan and died in San Diego on December 19, 1992. I found his dates of enlistment in the Navy and his social security number, which enabled me to obtain his military records from the National Archives.

I was relieved to realize that many of the biographical details that Barton shared with Archer were likely to have been true, something Archer seemed unsure of. Archer’s account added color to the cold contours of the data I found. For example, when speaking about his hardscrabble childhood, Barton used to sing an old song, "Down on Thoity Thoid and Thoid.” The 1940 Census lists Barton’s childhood address as 232 E. 26th Street, between Second and Third Avenues, just blocks from the corner of 33rd Street and Third Avenue in what was then a poor and working-class neighborhood.

When I returned to Los Angeles in fall 2018 to see the rest of the drawings at UCLA, I was greeted by members of the Special Collections staff, who were now as excited about the discovery of Barton’s work as I was. They showed me Henry Evans’s correspondence with the Library from 1971, when he donated the drawings: “I want them to stay together and be available so that when poor Rick is dissected by the graduate students and/or art historians they will have something of his to look at, instead of just repeating the bizarre stories about his admittedly bizarre life.”

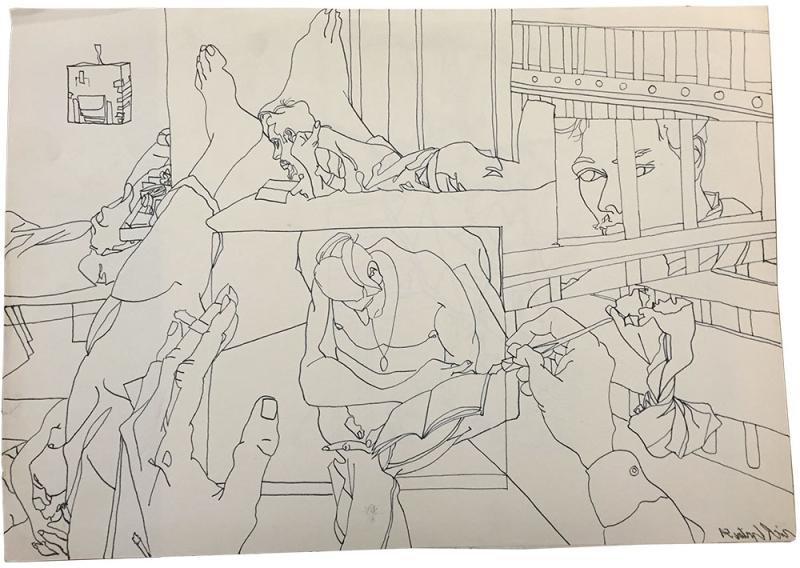

In this sensitive drawing, Barton draws his fellow inmates reading and peering through bars. He holds a cigarette in his left hand and a pen in his right. It is characteristic of Barton to include himself within a composition. Rick Barton (1928–1992), Untitled, 1959, pen and ink, 10 1/4 x 14 1/2 inches (26 x 36.8 cm). Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

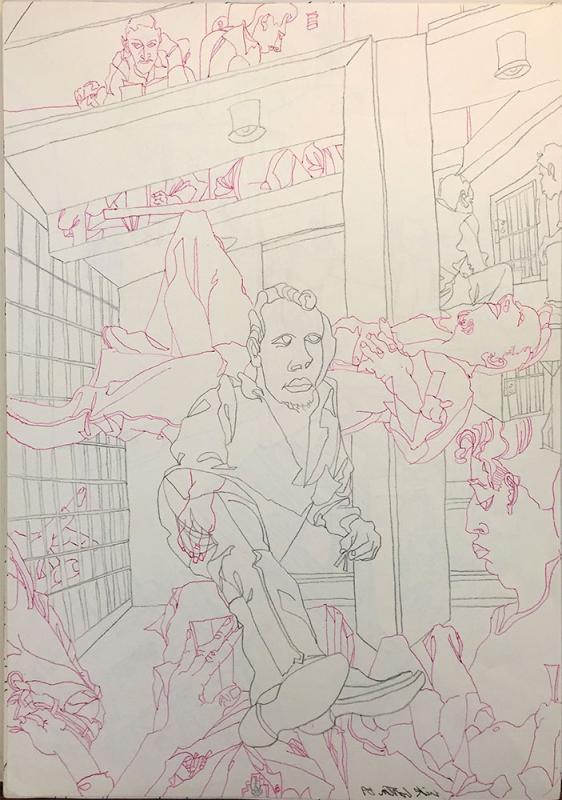

I was jittery with excitement when I entered the reading room. Well over six hundred sheets, nearly all dating from 1959 to 1962, were divided among eleven folders in a single archival document box. The first folder contained drawings Barton made in prison in 1959. This dovetailed with a discovery I had made earlier. On July 3, 1959, the Daily Independent Journal, a local paper out of San Rafael, reported that Barton had been arrested on narcotics charges in Sausalito, which was in those days a bohemian outpost of San Francisco. Barton rarely used color, but among the drawings he made while in prison were two-tone drawings in red and black or blue ink or graphite. The portraits Barton made of fellow inmates in 1959, and again in 1962, are profoundly humanizing. One drawing that I find particularly touching focuses on the activity of reading as a way to pass the time. Barton was himself an autodidact and an intellectual who sometimes imagined himself at the helm of an academy, which he dubbed the Academia Vinciana, in reference to an informal school of fifteenth-century Milanese intellectuals to which Leonardo da Vinci is thought to have belonged. (This is one possible explanation for Barton’s use of mirror writing.)

After an exhilarating few days at UCLA, I spent several hours at the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. It had been suggested to me by Dean Smith, an artist and archivist at The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, that Barton’s drawings resemble illustrations in gay liberation magazines of the 1970s. I wondered if I might identify the work of a follower, or even Barton himself, in their pages. New York Public Library’s “Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender periodical collection” had already provided me with an extensive overview, but there were a few loose ends I was hoping to tie up. Two artists I am particularly curious about are Nicholas Kouninos and another who signed his work as both Kenerin Murphy and Charles Murphy. Contributors to LGBTQ journals and chapbooks often used pseudonyms and the trail was fairly cold. Although this line of inquiry turned out to be relatively unfruitful, it is one I’m nevertheless grateful to have had the opportunity to explore.

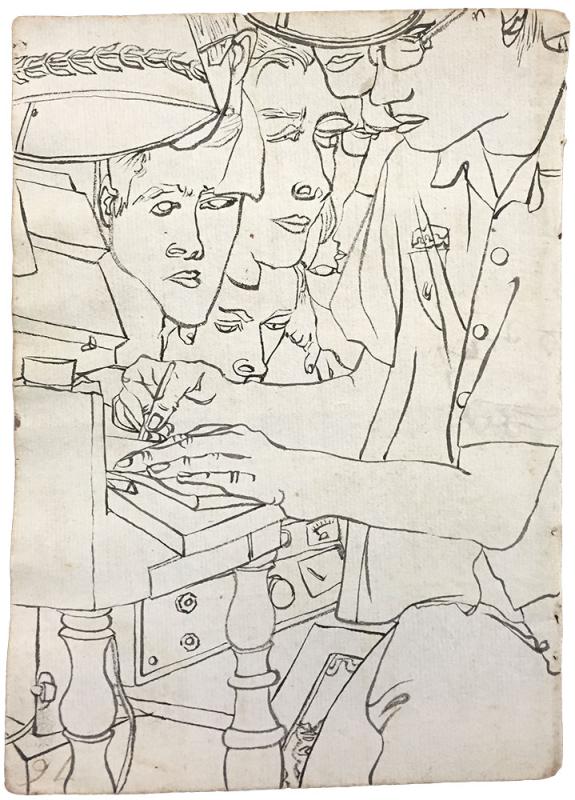

This small drawing of Barton’s hand inscribing his name backwards on a café table is a kind of self-portrait of the artist. Rick Barton (1928–1992), Untitled, 1961, pen and ink, 8 x 5 1/4 inches (20.3 x 13.3 cm). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

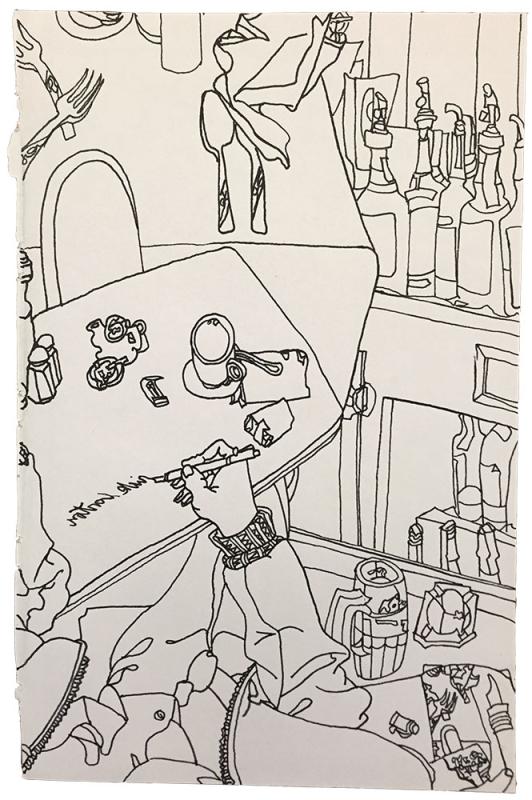

I like to think of this drawing as a representation of Barton’s Academia Vinciana, with eager pupils gathered around a master or fellow acolyte. Rick Barton (1928–1992), Untitled, pen and ink, 7 3/4 x 5 3/4 inches (19.69 x 14.61 cm). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Before returning to New York, I stopped in Chicago, where I visited the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University. I had noticed early on in my research that Northwestern owned many of the print portfolios that Barton published with Henry Evans between 1958 and 1962, as well as ten sketchbooks, several of which were described online as containing “panoramic pen and ink drawing[s] including many portraits and some places in San Francisco such as Foster’s [Cafeteria].” I was welcomed by the collection’s curator, Scott Krafft, with whom I had been corresponding for over a year. He had purchased the sketchbooks after becoming acquainted with Barton’s printed works, which entered the collection before his tenure. I knew from Archer, as well as from Etel Adnan’s 1998 essay, “The Unfolding of an Artist’s Book,” that the accordion-folded book was an important format for Barton, yet none were represented in the collection at UCLA. After seeing the books, which when extended range from approximately eight feet to nearly twenty, I was convinced that any exhibition of Barton’s work should include a sampling.

Several weeks after my trip, I presented my findings to colleagues at the Morgan, suggesting that Barton’s work fell into several distinct thematic groupings, such as “Ritual and Architecture” and “Intimate Interiors.” My co-workers quickly became Barton enthusiasts, encouraging me to expand the size of the exhibition. “Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton,” as the exhibition is called, will include some sixty drawings, two accordion-fold sketchbooks, and several print portfolios. Tentatively scheduled to go on view at the Morgan in the early months of 2022, it will mark the culmination of the activities I have described in this curatorial serial. I’m excited to share more of Barton’s extraordinary work—and the fruits of my ongoing research—in the exhibition and catalogue.

Images

All photos in this post are the author’s.

Rachel Federman

Associate Curator

Modern and Contemporary Drawings