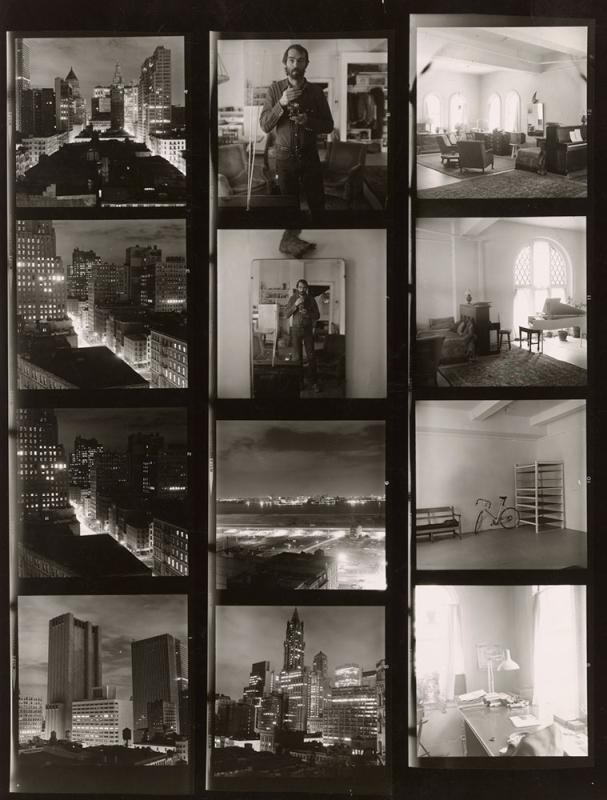

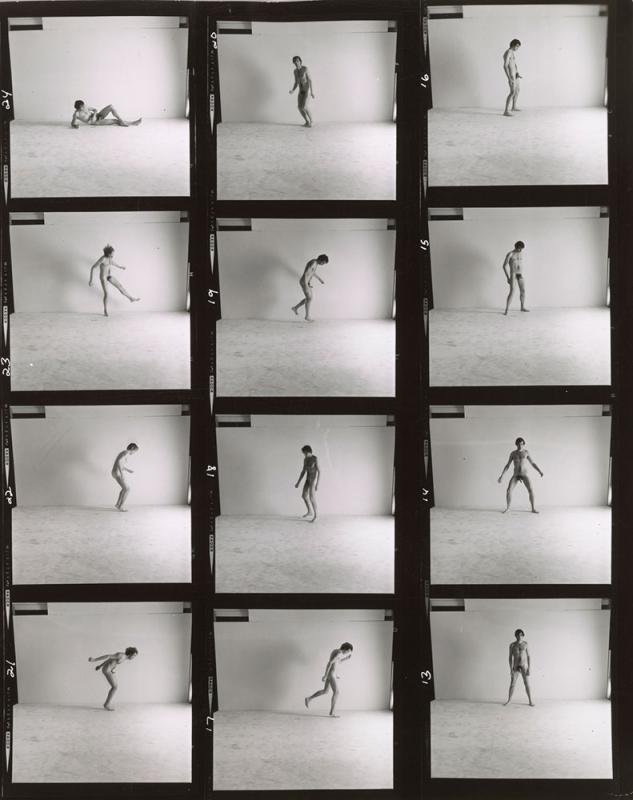

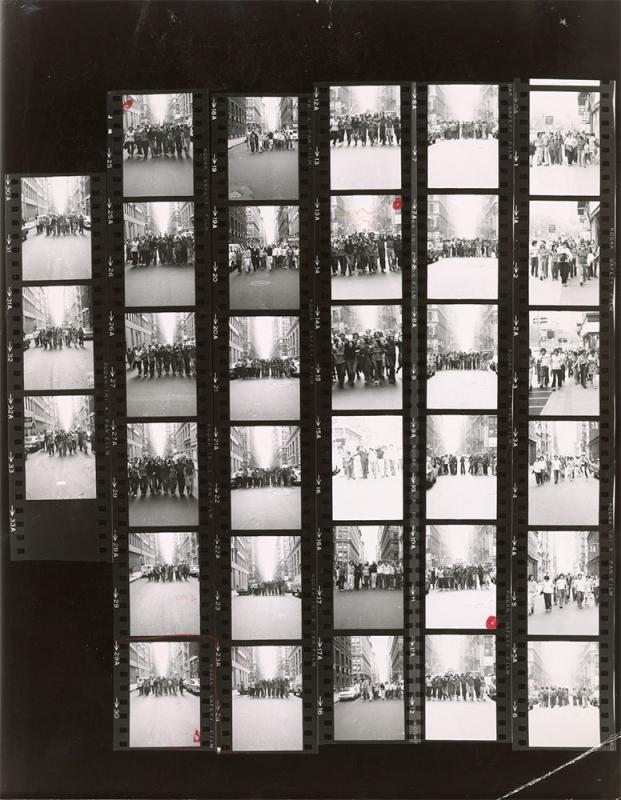

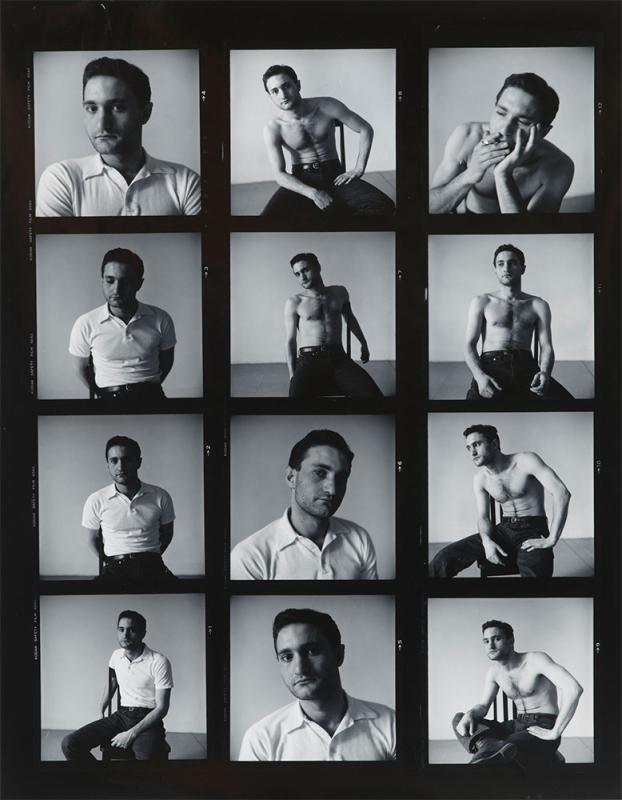

In 2013 The Morgan acquired one hundred photographs by Peter Hujar and, along with them, a vast collection of material including correspondence, job books, and contact sheets. The contact sheets were made between 1955, when Hujar was in his early twenties, and 1986, shortly before he died of AIDS-related pneumonia, and they demonstrate the range of Hujar’s practice. Contact sheets—test prints made from film negatives in contact with printing paper—are a tool for editing that often provide the photographer with a first glimpse of the contents of a roll of film. Eric Dean Wilson’s 2019 blog post “The Peter Hujar Collection: A Self-Portrait” highlights the relevance of Hujar’s contact sheets, describing “hauntings,” or parallels between the subject matter represented in Hujar’s photographs and Wilson’s own New York City summer so many years later. He writes, “Of course, in my three months at the Morgan, I didn’t get to every contact sheet, but I did manage to see a great many of them, if only with a glance.” Three years earlier, I did exactly that: I looked at every one of Hujar’s 5,783 contact sheets.

In summer 2016 I was one of the inaugural CUNY Graduate Center/Morgan Library & Museum Fellows. After the first week, following discussions with the photography department, I was struck by the existence of three independent organizational systems associated with the material. Hujar had his own method for numbering his contact sheets, assigning them what are known as “job numbers”; he often wrote this number across the verso of the sheets corresponding to a job. After his death, the Estate of Peter Hujar created their own numbering system. And when the sheets came to the museum, each was given a unique Morgan accession number. Upon learning that there was no concordance yet linking these three sets of identifying systems, I proposed spending the 120 hours of the fellowship period creating a spreadsheet that could later be uploaded to the museum’s collection database.

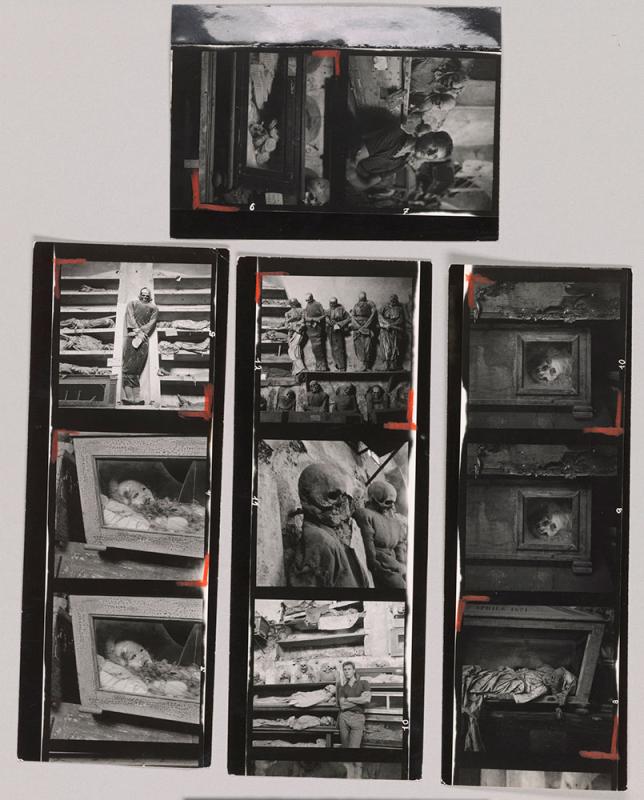

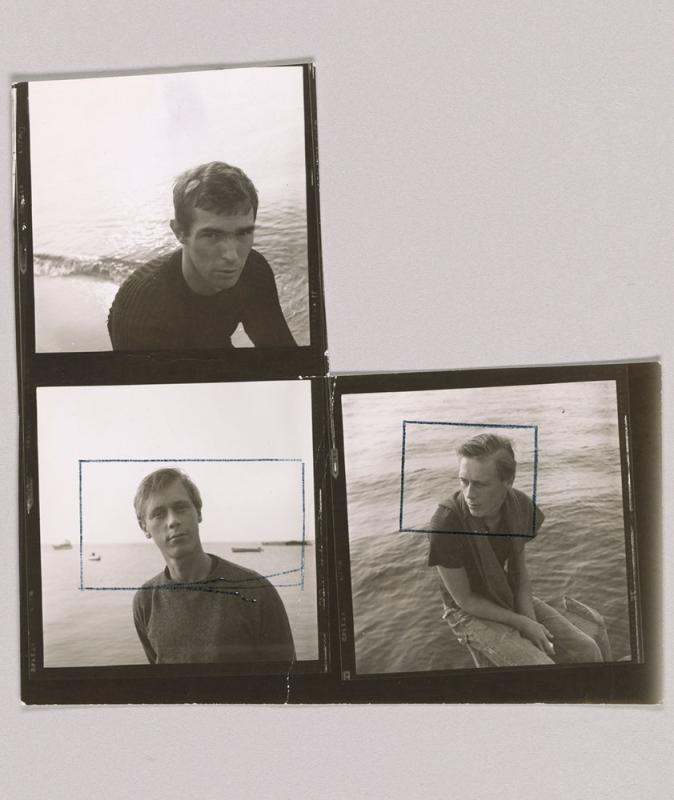

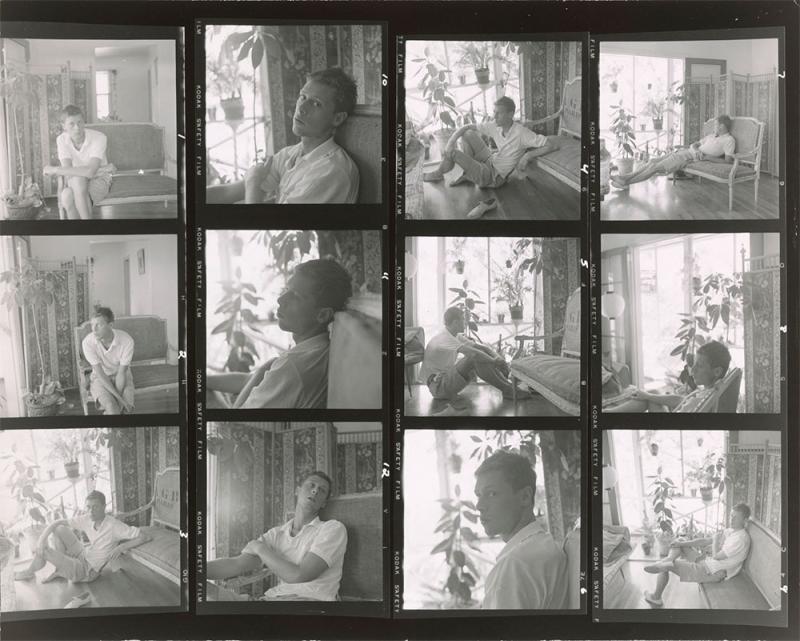

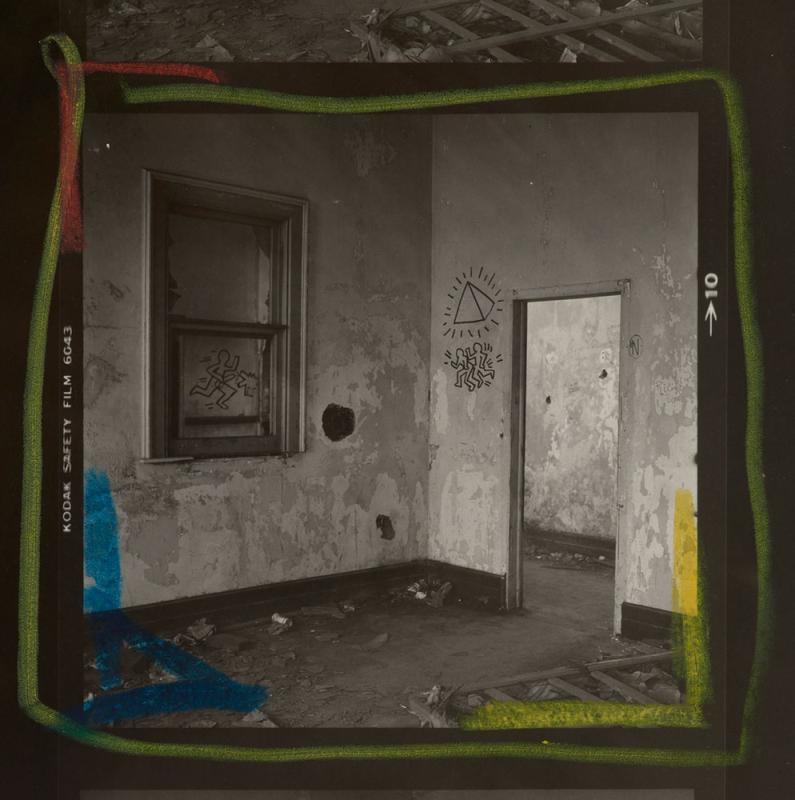

As a historian of photography, I generally learn about a photographer’s career through the artist’s final prints. By contrast, my introduction to Hujar’s oeuvre consisted of thumbing through thousands of test prints. Many of the contact sheets reflect paid work, most often portraits. Others show quiet moments at home, or intimate sexual encounters. Some of the contact sheets exist in pieces—instead of an 8x10 inch sheet exhibiting all twelve of the exposures on a roll of 120mm film, what survives are strips of two or three squares, or a sheet with frames cut out and missing. On occasion Hujar would give a contact frame to the subject or mail one to a friend, without regard for the completeness of his file records. (The Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, which administers the artist’s estate, retains his negatives).

Over the fellowship period, I systematically worked my way through all eight of the bankers boxes filled with Hujar’s contact sheets. Within the boxes, the contact sheets are held in folders organized by job numbers (chronological, for the most part). I labeled each folder with all three of the corresponding numbering systems, while making sure that each contact sheet was safely stored in a polypropylene photo sleeve. Most of my time was spent examining each print to verify that it had a unique Morgan number, and then collating all of the existing information into the spreadsheet. The result was not a finished product with polished information on each roll of film Hujar exposed, but rather a starting place for future scholars to embellish (and, in the meantime, a way to make a contact sheet identifiable by any of the three numbering systems). While the work was largely tedious, it also provided a unique view into the life of a photographer.

Often, as I progressed through the bankers boxes, I found myself cautious of intruding on Hujar's privacy. I followed his travels to Italy, to Mexico, and back to Italy. The contact sheets also chronicle a period of gay life in New York City, from afternoons spent with his friends on Fire Island to cruising on West Side piers. There is an intimacy that comes not only from the subject matter, but from the format of photographs: on contact sheets, each image is seen at the palm-sized scale Hujar saw when he looked down into the ground glass of his camera. These contact sheets, marked with grease pencils to highlight a preferred frame or a note for cropping a future print, filled with outtakes and mistakes, are the artist’s rough drafts: like so many treasures at the Morgan, objects never intended for public consumption that are, nonetheless, full of lessons for anyone who appreciates an artist’s mastery.

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life—on view at the Morgan from January 26 through May 20, 2018—presented one hundred and forty photographs by this enormously important and influential artist.

All images: Gelatin silver print contact sheet. © The Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Leila Anne Harris

Edith Gowin Curatorial Fellow

Photography Department

The Morgan Library & Museum