This is a guest post by Eric Dean Wilson, writer, educator, and doctoral student in English at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

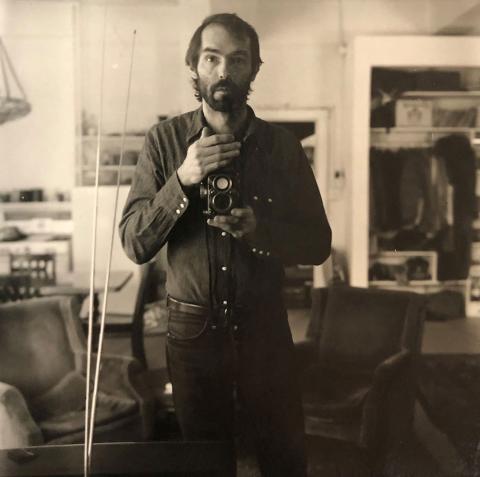

Self-portrait of Peter Hujar in 2nd Avenue apartment mirror, New York City, 1976. © The Peter Hujar Archive / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

I’d spent two weeks in the Morgan Library & Museum Sherman Fairchild Reading Room when María Molestina offered to take me to see where they store the Peter Hujar Collection. It’s a humbling experience to see spread before you a life in boxes. I knew that every item within these thirty or so variously sized boxes related, in some way, to the life and career of Hujar. Since I’d combed through the eighteen-page finding aid, I also knew that the collection amounted to “Approx. 18 linear feet,” a difficult quantity to picture. How much space is filled by thirty-one containers?

As a doctoral student in the English Program at CUNY’s Graduate Center, I’d come to the Morgan to be one of their summer fellows. I was to work on a project related to photographer Peter Hujar (1934–1987). The Morgan had acquired the transcript of a 1974 interview between Hujar and the writer Linda Rosenkrantz, a close friend of his. In the interview, Hujar recounts everything he did on the previous day in vivid—at times, humorous—detail. My task was to locate materials in the collection that could flesh out the context of people and places Hujar mentions: letters, postcards, audio, and, of course, photographs.

Hujar’s morning starts with a phone call from Susan Sontag, who wants to see his photography show in SoHo but isn’t sure where Broome Street is. (“A little out of touch” is Rosenkrantz’s response to that.) Afterward, a French editor from Vogue rings Hujar’s Second Avenue apartment to pick up the prints of a commercial shoot with supermodel Lauren Hutton. In the afternoon, Hujar walks to Avenue C to shoot a portrait of a grumpy and distrustful Allen Ginsberg for The New York Times. At night, Vince Aletti—Hujar’s close friend, who would later become art editor for The Village Voice—drops by to use his shower and order Chinese food. Finally, after some work developing prints (he’s unhappy with the Ginsberg shots), he plays a Bach piece on his harpsichord (!) and falls asleep to the “shop talk” of the sex workers on the street.

The interview was part of a larger, unrealized project. Rosenkrantz had planned to conduct a number of interviews with different artists, each conversation a kind of day-in-the-life, a textual portrait of the artist. But, as you can guess from the above description, the interview is as much a portrait of a certain slice of 1970s New York as of Hujar. The transcript is a snapshot of the kinds of intimate artistic communities once possible in downtown Manhattan, now rare, if extant at all.

Standing before the banker’s boxes and shoebox-like containers, I was surprised to be able to see the collection all at once. And yet the visibility is an illusion. The boxes fail to reflect the vibrant life—lives, really—concealed within them. At the end of my fellowship, after 120 hours in the Reading Room, I would feel that I’d only glanced at some of the items in the collection.

Hujar is best known for his portraits of visionary artists, poets, intellectuals, musicians, and queer icons around New York City in a period spanning roughly the late-1950s to the mid-80s. In one of these boxes, a copy of a 1975 issue of Art Direction quotes Hujar himself identifying his work as “[p]rimarily people…and usually in black and white.” Even so, his picture-taking exceeds this simple description. His portraits extend to people whose names would never be known, to careers that would never quite launch, to people on the street, to men he cruised on the pier. His subjects also transcend the category of the human: a boa constrictor named Skippy, for instance; or a stately Shar-Pei named Will; or the nameless cows and sheep on a New Jersey farm; or three circus elephants, their feet in chains, staring with eyes that appear to reflect total exhaustion. I would even categorize his photographs of trees, grasses, the Hudson River waves, and the derelict Chelsea piers as portraits of the material world. And though Hujar worked primarily in the genre of portraiture, some of his most stunning work is better categorized as street photography or erotica.

The eight boxes of photographic contact sheets are the crown jewels of the Peter Hujar Collection. There are about 5,783 sheets. Each complete contact sheet from his medium-format Rolleiflex—which is to say, the vast majority—contains twelve square images, small tests to see whether or how he wanted to print larger versions. That’s around 60,000 images, most of them never before published or otherwise made public outside of the archive. And the descriptions of each contact sheet are still a work in progress, which means that, at times, as I pulled out a folder with a label like “Night flash New Jersey / 2) Andy Warhol,” I was never quite sure what I would see. (In that particular case: trees, a diner, telephone poles taken with a bright flash, and yes, in the corner, two images of Andy Warhol reading a newspaper).

Through the weeks of sifting through these contact sheets, I began to feel as if I were being haunted by the subjects. One weekend I went to IFC to see the remastered version of Frank Simon’s 1967 film The Queen, which documents the Miss All-America Camp Beauty Contest (a drag queen beauty pageant) held that year in New York City. The film is famous for a moment toward the end, when Crystal LaBeija, a Black queen representing Manhattan, is awarded third place. In protest, she walks offstage, calling foul play after the pageant has concluded. (A young white queen from Philadelphia wins.) When LaBeija claims that the contest was rigged, one of the white organizers snaps back that LaBeija lost because she’s “showing [her] color.” LaBeija, in a moment of gorgeous ferocity, shouts back: “I have a right to show my color, darling! I’m beautiful, and I know I’m beautiful.” Partly due to that experience, LaBeija would go on to help found the New York City ballroom scene, whose participants were mostly queens of color, and the legendary house of LaBeija that’s immortalized in Paris is Burning, not to mention the current FX show Pose. A week after seeing The Queen, I opened a folder labeled “Drag Ball / Palm Gardens,” and there, in the bottom-left corner, was, unmistakably, Crystal LaBeija. The date is 1966, the year before she got snubbed. Hujar had caught a legend in the making.

Another haunting came soon after. The city was gearing up for World Pride, the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Images of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two trans activists of color who were vital leaders in the struggle for gay rights, appeared all over the city. The week following Pride, I looked at a contact sheet from 1976 described as “Easter Sunday at St. Patrick’s / pier / buildings / plus view from World Trade Center.” Hujar had trekked from Midtown to the West Side and, finally, to the Financial District, taking photos along the way. At the piers, Hujar stopped to cruise (presumably) and shoot portraits of a beefcake in impossible short shorts and knee socks. Among these are four shots of an almost unrecognizable Marsha P. Johnson, dressed curiously in a white robe and keffiyeh-like headdress, the “Om” symbol emblazoned on her chest. In only one of them does Johnson smile—and the smile gives her away. Later, in a contact sheet from Halloween night 1979, Hujar runs into her again, this time in her usual regalia: a white chiffon dress, heavy make-up, and a flower in her flowing hair.

These two encounters are only an infinitesimal fraction of the narrative that emerges from the contact sheets, a narrative that spills from the historical bounds of Hujar’s time and touches our own. Of course, in my three months at the Morgan, I didn’t get to every contact sheet, but I did manage to see a great many of them, if only with a glance. Unlike many of his fellow portrait photographers, Hujar caught not only the lives of his subjects but the city that gave them life as well. And in preserving the tumultuous New York decades from post-War prosperity to the height of the AIDS crisis, Hujar—deeply complicated man that he was—managed to capture himself, fragmented and spread throughout tens of thousands of exposures.

On one of my last days in the reading room, I felt as if I were visited by the presence of Hujar himself. From the finding aid, I ordered “Peter Hujar’s Wallet.” It wasn’t immediately relevant to the interview I was working on—but why not? As far as I could tell, this was Hujar’s last wallet, the one he owned when he was admitted to the hospital and, later, died of AIDS-related complications in November of 1987. It arrived in a manila folder. Inside, a gray-and-navy velcro wallet lay open, Hujar’s Chemical Bank and CitiBank cards immediately visible, his Medicaid card tucked behind those, and a white card with the label CLINIC: 403, with hospital information. Inside one of the velcro pockets were two quarters and two subway tokens, which would never be used. A second pocket revealed a green fabric scapular with an image of the sacred heart of Mary, a heart dripping with blood. Around the heart are the words: “Immaculate Heart of Mary, pray for us now and at our hour of death.” For the first time all summer, I had the distinct feeling that I’d somehow crossed a line, as if I had invaded his privacy. I carefully returned the cards and tokens to their respective pouches. I found myself silently asking someone—was it Hujar?—for forgiveness.

Perhaps it’s unfair to call the collection, as I did, “a life in boxes.” No life—certainly not one so protean as Peter Hujar’s—can be condensed to the archival shelf. And yet this is, perhaps, the closest experience we have to conjuring the dead. That way of framing certainly falls in line with Hujar’s monograph: Portraits in Life and Death. Susan Sontag, in her introduction to the book, claims that “Photography…converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also—wittingly or unwittingly—the recording-angels of death.” And so, in a way, are the archivists—at the Morgan and elsewhere—who, in attending to the objects of the dead, cultivate life.

Special thanks to Photography Curator Joel Smith and to the gracious staff of the Reading Room: María Isabel Molestina, Polly Cancro, Sylvie Merian, Sophie Harding, and Hannah Laren. Thank you for an incredible summer.

Eric Dean Wilson is a writer, educator, and doctoral student in English at the Graduate Center, CUNY. His research typically falls within the realm of Environmental Humanities as it intersects with visual culture and American queerness. A graduate of The New School's MFA program, he's published a number of creative nonfiction pieces and is currently working on a book that explores the history of Freon and the impact of air conditioning on the climate crisis. He teaches writing at Queens College.

Eric Dean Wilson is a writer, educator, and doctoral student in English at the Graduate Center, CUNY. His research typically falls within the realm of Environmental Humanities as it intersects with visual culture and American queerness. A graduate of The New School's MFA program, he's published a number of creative nonfiction pieces and is currently working on a book that explores the history of Freon and the impact of air conditioning on the climate crisis. He teaches writing at Queens College.