This is a guest post by Madeleine Barnes, a writer, visual artist, and doctoral candidate in English Literature at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

This summer, I was given the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to research and write detailed catalog descriptions of nineteenth-century women’s letters during a summer fellowship at the Morgan Library & Museum. As a doctoral candidate studying English Literature at The Graduate Center, CUNY, I was honored to have the opportunity to work on letters from the collection of scholar Gordon N. Ray, who bequeathed his holdings to the Morgan.

Under the supervision of Senior Cataloger Sandra Carpenter, I worked on a group of fifty-one letters written by Maria Tunno (1783–1853), a resident of Buckinghamshire who had a large family and a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. The letters span 1816– 1821, when Maria was in her early thirties. I could not have anticipated the tremendous impact this project would have on my life and studies. As COVID-19 reconfigured life in New York City and beyond, I traveled back in time, learning from Maria Tunno’s creativity and resilience.

Maria Tunno’s Life and Letters

My research focuses on how women use forms of self-expression coded and denigrated as feminine, like weaving and embroidery, to regain agency in the aftermath of violence, or in the absence of other forms of communication. I study women’s correspondence and diaries to see what they reveal or omit about women’s lives in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so I read Maria Tunno’s letters with an eye toward topics that people might misconstrue as “unimportant,” interested in how her letters maintained and fortified bonds between women in her family.

Because she was unmarried, much of Maria’s life is undocumented. She was born in America, the first daughter of Scottish emigrants John and Margaret Tunno. John Tunno and his brothers originally moved from Kelso, County Fife, to South Carolina in search of better economic prospects. Shortly after Maria’s birth, her family was exiled to England due to her father’s Loyalist sympathies during the American Revolution. Several Tunno brothers remained in America to continue successful mercantile careers and appear to have been involved in the slave trade to some extent—a fact that goes unmentioned in these letters and merits further research.

Omissions in letters are fruitful ground for questions regarding gender roles, letter-writing, privacy, and legacy. What aspects of family life were off-limits? Jane Austen’s family burned and cut out passages from her letters after her death. Curiously, Barbara L. Bellows writes that John Tunno’s children were not told about their cousins in America. 1 It is possible that Maria was told something in private about her uncle’s lives, but we currently have no way of knowing. She may have been disinclined to discuss anything improper, or she may have been entirely uninformed.

Women faced pressure regarding what they wrote in letters. In the introduction to Jane Austen’s selected letters, Vivien Jones writes about how E. M. Forster deemed Austen’s personal letters bereft of “important” topics: “She takes no account of politics or religion, and none of the war…” 2 Austen corresponded with her sister Cassandra about daily life, including domestic issues, anxieties about marriage and money, family news, and humorous accounts of social events. Jones calls Austen’s letters to Cassandra a “resource for the subordinated,” noting that “The primary resource is the intimate emotional bond between the sisters, but of almost equal importance is writing itself, through which that intimacy is enacted and sustained.” 3

The Materiality of Care

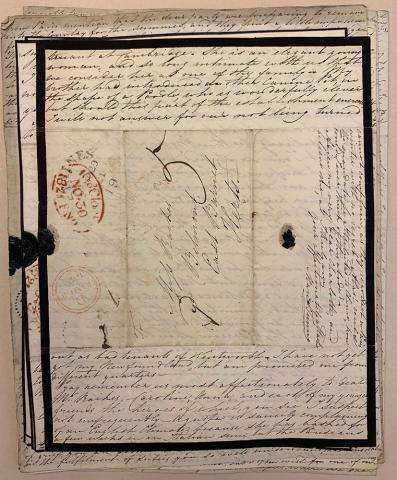

Studying the letters, I was captivated by their tactile elements. Some letters are written on black-edged mourning stationery—like a mourning dress, this stationery is used when a person is in mourning, as Maria often was. A recipient of a letter on this paper would immediately understand that the sender was grieving. Mourning stationery is an interesting artifact to hold and touch—the visual representation of loss adds gravity to time-worn letters. We are living through a period of collective grief and sorrow that invites us to re-examine unusual objects that mitigated grieving processes of the past. The practice of using mourning stationery has origins in the seventeenth century and remained popular for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. 4 The mourner would begin with paper that had a thick black border, which would narrow and eventually disappear as their grief dissipated. I suspect that present-day society could benefit from material representations of grief and its stages, which can be difficult to communicate and picture.

MA 14344.37, autograph letter signed from Maria Tunno, with postmarks and seal, written on black-edged mourning stationery, 1821, page 4.

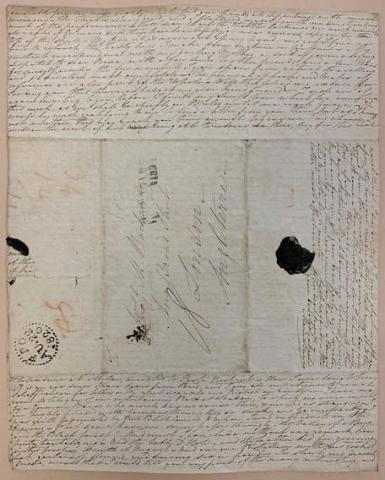

Maria’s letters are housed in intricately painted portfolio boards. She used a variety of wax seals, some featuring thistles, Scotland’s national emblem. One seal displays a butterfly and the Italian phrase, “Vita non lunga ma felice”, which roughly translates to, “not a long life, but a happy one,” a sentiment informed by the reality of early death in the nineteenth century. Letter writing was a way for women to console and support one another through life’s uncertainties. Maria signs most of her letters with the farewell salutation, “Your devotedly attached, Maria Tunno.” Her letters are filled with subtle and overt expressions of care. Writing about care communities in nineteenth-century literature, Talia Schaffer observes that Victorian literature “is a literature that centrally thinks, and mourns, about care.” 5 My engagement with correspondence from this century has deepened my interest in the materiality of care.

The rules associated with cataloging instilled a sense of order during a summer destabilized by an illness that thrives on our biological need for human connection. I appreciated the objects in the cataloging office and worked surrounded by bone folders, magnifying glasses, rulers, foam wedges, hi-polymer erasers, pencils, acid-free paper, and soft brushes. I liked the protocols: wash your hands, bring a sweater—the room is kept cool to slow chemical reactions that may cause materials to deteriorate. Working on-site at the Morgan during a time of reopening was astonishing. To see firsthand that people still need art was moving.

MA 14344, Portfolio Boards of Maria Tunno, 1783-1853.

Reflections on Interdependence

I lived vicariously through Maria’s descriptions of her journeys to cities like Brussels, Geneva, Paris, Edinburgh, and Rome. She and her family went abroad after her father died, hoping that a change of scene would restore their spirits. True Scots, they followed a route in the Scottish Highlands that paralleled Sir Walter Scott’s poetic romances. As the eldest sister, Maria had been heavily involved in managing her father’s care at home; the importance of distancing herself from his deathbed cannot be overstated. She wrote of the unphilosophical horror she experienced during his last eight hours, during which she never left him.

MA 14344.27, autograph letter signed from Maria Tunno, Paris, France, to Mrs. J.M. Raikes, 1820, page 4.

The most memorable letters are those in which Maria contemplates sublime scenes that drew her mind out of itself. One letter describes hiking Mount Rigi and reflecting on the life of a Mountaineer:

The range of Mountains which first presents itself on gaining the summit of the Rigi is truly striking to the English eye—infinitely more than the fourteen lakes and vast extent of country over which the eye bounds in looking from the height…I could then for the first time trace the characteristic independence of the Mountaineer, who, in an insulated locality accustomed to rely only upon his God and his own exertions becomes insensible to the sympathy in which his more gregarious fellow creatures feel necessary to existence. To one who has been used to the atmosphere of human sympathy, independence would be but a bad exchange, and much as I enjoy a peek at the mountains, I never felt more in humor with our netherworld, than when experiencing even a day’s residence so far above its level.

Due to my research focus on women’s agency and independence, I was surprised by this passage—Maria looks down from Mount Rigi and is overcome with the feeling that independence would be a “bad exchange” to anyone who has known “human sympathy.” Maybe I wanted this moment to serve as a welcome respite from her bereavement and social responsibility. Instead, her hike and the surrounding splendor lead to an appreciation of people and care. Although solitude can be fruitful, the pandemic taught me the irreplaceability of human connection, making this passage understandable.

Notes on Critical Cataloging

When I started this project, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to learn more about how women’s letters and other primary sources are professionally cataloged at the Morgan. I learned that how we describe items from underrepresented cultures, groups, and individuals holds great significance, and that catalogers have an opportunity to intervene and ensure that the language we consciously use does not perpetuate systemic bias and discrimination. As I worked, I was guided by the Morgan’s Statement on Critical Cataloging, which reminds us that the goal is “to improve access to these works by enhancing their descriptions in a sensitive, respectful, and accurate manner.” I felt that my role as one of the few people reading Maria Tunno’s letters was to catalog them to the best of my ability and ensure that they were described in detail and with respect. It was a joy to learn about critical cataloguing processes at the Morgan as I studied women’s lives and letters; most of all, I loved working with people who ensure that women’s letters live on.

Endnotes

- Barbara L. Bellows, Two Charlestonians At War: A Civil War Odysseys of a Lowcountry Aristocrat and a Black Abolitionist (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2018) p. 27.

- Vivien Jones, introduction to Selected Letters by Jane Austen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. xi.

- Jones, introduction to Selected Letters by Jane Austen, p. xxiv.

- David Barton, Nigel Hall, Letter Writing as a Social Practice (Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2000), p. 99.

- Talia Schaffer, Communities of Care: The Social Ethics of Victorian Fiction (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2021), p. 64.

Madeleine Barnes is a writer, visual artist, and doctoral candidate in English Literature at the Graduate Center, CUNY. Her research focuses on women’s domestic embroidery, poetry, and life writing as forms of public and private resistance in Early Modern and Victorian England. She is the author of the full-length poetry collection You Do Not Have To Be Good, published by Trio House Press in 2020, as well as four chapbooks, including The Memory Dictionary, forthcoming from Ethel Press in fall 2022. She is a Mellon Foundation Public Humanities Fellow with the PublicsLab and serves as Poetry Editor at Cordella Press. Find her at madeleinebarnes.com.

Madeleine Barnes is a writer, visual artist, and doctoral candidate in English Literature at the Graduate Center, CUNY. Her research focuses on women’s domestic embroidery, poetry, and life writing as forms of public and private resistance in Early Modern and Victorian England. She is the author of the full-length poetry collection You Do Not Have To Be Good, published by Trio House Press in 2020, as well as four chapbooks, including The Memory Dictionary, forthcoming from Ethel Press in fall 2022. She is a Mellon Foundation Public Humanities Fellow with the PublicsLab and serves as Poetry Editor at Cordella Press. Find her at madeleinebarnes.com.