The Morgan has acquired thirteen letters written by the American writer J.D. Salinger (1919–2010) to his editor at The New Yorker in the 1940s and 50s, Gustavus “Gus” Lobrano (d. 1956). The letters are part of a larger acquisition of letters, manuscripts, and printed books related to Gus Lobrano and his daughter, Dorothy “Dotty” Lobrano Guth (1928–2016), who also worked at The New Yorker.

Lobrano was fiction editor at The New Yorker from 1938 to 1956 and played a central role in publishing the short fiction of writers like J.D. Salinger, editing several of the author’s most famous stories. Lobrano has generally been acknowledged for influencing and shaping J.D. Salinger’s short story writing, but very little of his correspondence with Salinger survives (what survives is part of the New Yorker Archives held at New York Public Library).

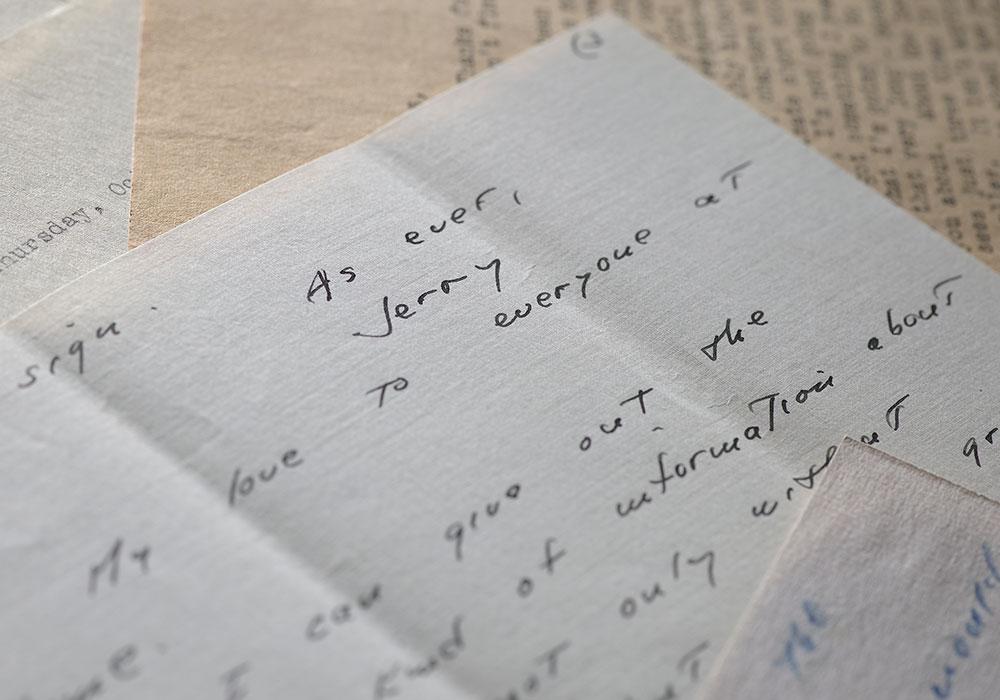

The correspondence offers an extraordinarily intimate view of the relationship between an author and his editor. Nearly every letter contains significant literary content—rare for Salinger correspondence—specifically about the composition, revision, and/or publication of “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” “Teddy,” “Franny,” “Zooey,” “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” and several unidentified and/or lost stories.

In two of the letters to Lobrano, Salinger discusses the rejected (and now lost) story “Requiem for the Phantom of the Opera,” revealing new details about the work that centered on Holden Caufield’s younger brother, Allie, referenced at several points in The Catcher in the Rye. Lobrano’s rejection letter survives at New York Public Library, but the two letters Salinger wrote Lobrano directly before and after receiving that rejection illuminate not only the content of the story but the difficulties Salinger faced writing about another Caufield family member in the wake of Catcher. He even compares the process of writing the piece to his experience working with Lobrano on “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” one of his most famous stories. That was a time when, in Salinger’s words, he had “that old discipline and forbearance”—something he wishes he could capture yet again.

The letters are particularly revealing of the composition of “Zooey,” as it was revised from a larger book project titled “Ivanoff the Terrible” into a story first published by The New Yorker in 1957. Very little was previously known about Salinger’s composition of “Ivanoff the Terrible”/ “Zooey.” The letters reveal how much Salinger struggled to write and revise this work in 1955:

I’ve never had so much trouble with my writing in my life. So many times I’ve all but abandoned the book—and the profession—and thought about selling the house and going off somewhere….For over six months now I’me [sic] been working on just one single weekend sequence of the book. And not even a whole weekend, but just a single Saturday morning, afternoon, evening, and night…. This Saturday now runs close to 200 pages, and there are three fair-size scenes to go still…. I wonder if I ought not to shelf the whole book and break it down into three or four independent short stories. I really don’t want to do that, though. I’m so unattracted to that idea. In a way, ever since The Laughing Man, I’ve never been really attracted to the form. I know I’ve done good stories since then—including the Esme story, and Teddy—but in my own mind, at least, I hit some sort of apogee, to put it dramatically, while the Laughing Man was in the works.

The correspondence also contains numerous references to Salinger’s famously private personal life. In this letter, announcing his move to rural New Hampshire in 1953, he describes how the new setting is conducive to his work:

I’ll spare you an introspective analysis of How I Work Best—you know all that, anyway—but I will just say that I’ve always liked working under these or similar conditions. That is, when I’m absolutely alone and unconditionally obscure. I haven’t even a phone …

In the long, final letter of the group, sent to Lobrano when he was dying of cancer in early 1956, Salinger expresses how aimless he would feel without his editor’s guiding hand: “I’d never write for the magazine again. My God I’d be so lost.” Letters such as these show just how close Salinger was to Lobrano: they were not just colleagues but close friends, their letters as likely to mention tennis and trout fishing as the craft of the short story writer.

The Morgan now has one of the most significant collections of J.D. Salinger letters in the world, with correspondence dating from the 1940s to the 2000s. The letters to Gus Lobrano fill a previous gap covering his literary work in the 1950s, when Salinger was at the prime of his career.

The Salinger letters have come to the Morgan as the generous gift of Dorothy Jean Guth—Gus Lobrano’s granddaughter—in memory of her mother, Dorothy Lobrano Guth. Dorothy “Dotty” Lobrano Guth was a long-time New Yorker editor, like her father, and published The Letters of E.B. White (Harper Collins, 1976). White was one of her father’s best friends and also her godfather. Many of the books and letters contained in the archive acquired by the Morgan are addressed to Dotty.

The remainder of the archive comprises letters and manuscripts written by or to Gus and Dotty Lobrano, including correspondence with E.B. White, Carson McCullers, John Cheever, and Kay Boyle, as well as New Yorker editorial staff members such as Harold Ross, Katharine White, and Bill Shawn.

The collection also includes over a hundred printed books by mid-century American writers, most inscribed by their authors to Gus and/or Dorothy Lobrano. Highlights include a copy of E.B. White’s Stuart Little bearing the following inscription: “Gus, this book is outwardly rich and generally tedious and has been refused admittance to the NY Public Library because the writer is a 'bitter frustrated man' and the central character is a monster. Hope you like it - Andy.”

The collection will be cataloged in the coming months and made available for consultation in the Morgan’s Sherman Fairchild Reading Room.

Philip Palmer

Robert H. Taylor Curator and Department Head

Literary and Historical Manuscripts

Morgan Library & Museum