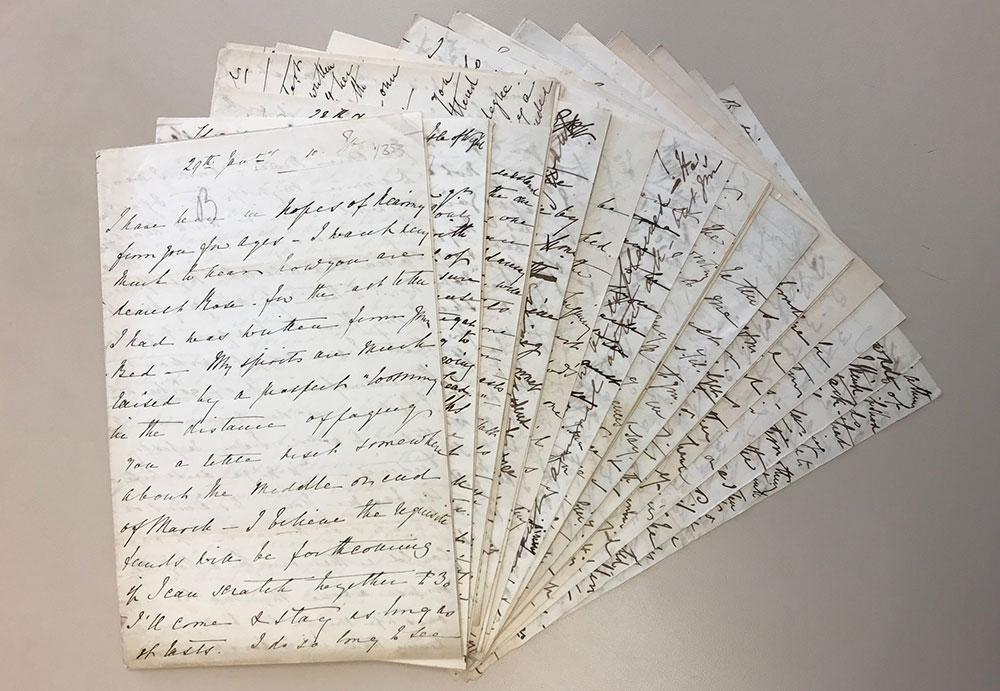

The shelves of most rare book and manuscript libraries contain their fair share of mysterious items of unidentified origin or authorship, residing in obscurity beside works by the famous and celebrated as a lingering challenge to contemporary catalogers and researchers. The reasons for their anonymity may vary, such as a lack of accompanying documentation, handwriting that is difficult to decipher, lack of a legible signature, or the obscurity of the subject or creator. Of particular interest are those materials related to the histories of marginalized or underdocumented groups of people which may have lain fallow for years owing to the challenges inherent in bringing the lives of their subjects to light. As the Gordon Ray Cataloger at the Morgan Library & Museum, I was recently faced with the task of cataloging a group of fifteen unidentified letters bequeathed to the Morgan by collector and literary scholar Gordon N. Ray (1915–1986) as part of a larger collection of manuscript correspondence addressed to the Anglo-French novelist, journalist, and political writer Rose Blaze de Bury (1813–1894). A notable figure in her day, she is today almost entirely forgotten despite her prolific career as an author of novels, journal articles, and numerous works of social and political commentary, as well as her unusual status as a woman actively engaged in the world of European politics. The letters, signed only with the initials “FMB”, appear in Ray’s own original inventory with his brief description:

“Written by a young unmarried lady living at 10 Grosvenor Square. They provide a lively picture of English literary and political society, set forth with great candor. Worth publishing.”

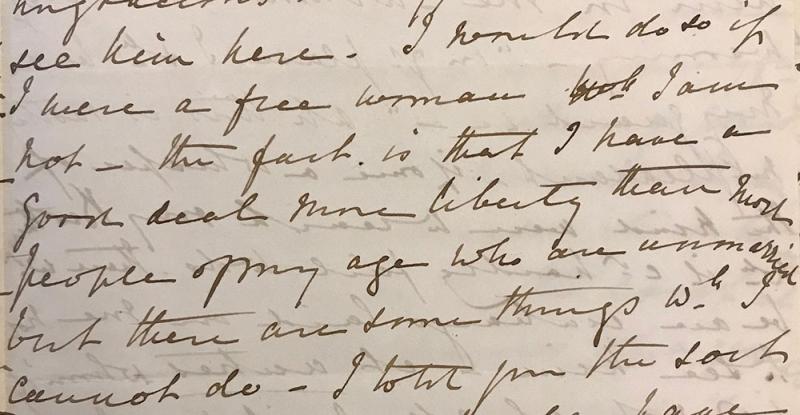

A preliminary review of the letters bears out Ray’s assessment. The unknown woman who sent them was evidently actively involved in the intellectual and artistic circles of 1850s London, and her observations on literary and political topics, as well as on contemporary society, are written with engaging humor and frankness. But who was she? The letters are full of references to friends and acquaintances, as well as to a brother (“John”) and various extended family, but include nothing that sheds light on the surname or identity of the writer. The address proved similarly unhelpful. It was not until I came across a reference to a second brother, Edward, along with the information that he was shortly departing aboard the HMS Cressy, that I was able to pursue a clue to the writer’s identity. The names of individual ships in the Royal Navy, along with their specifications and officers lists, were published year after year as a matter of general interest. Consulting the entry for the HMS Cressy in The Navy List of 1854, I lit upon the name of Lieutenant E. A. Blackett. Further digging revealed his full name, Edward Algernon Blackett, along with the names of his brothers, John Fenwick Burgoyne Blackett and Montagu Blackett, and most importantly, a sister, Frances (“Fanny”) Mary Blackett (1822–1895), better known to her contemporaries as Madame du Quaire following her marriage to Claude Felix Henry du Quaire in 1857. (Blackett’s marriage ended shortly thereafter with her husband’s death in 1860). A close friend and confidante of Matthew Arnold and Robert Browning, Du Quaire maintained a wide circle of artistic and literary acquaintances throughout her life, counting among her close friends a number of prominent literary figures of the day, as well as a wider circle of associates that included Henry James, de Tocqueville, Oscar Wilde, Rossetti, Whistler, and Augustus Hare.

List of officers for the HMS Cressy, with the name of E. A. Blackett, who was appointed Lieutenant on December 31, 1853 (The new Navy list. London: Parker, Furnivall, and Parker, 1854, page 227; accessed through Google Books)

By all accounts a memorable and imposing figure, Blackett was widely known for her generosity and cheerful disregard for the more narrow dictates of social convention and decorum: “Did you ever hear of Miss Blackett, whom we knew in Paris - the sister of the member of parliament?” writes Elizabeth Barrett Browning to her sister-in-law, Sarianna Browning, “She is a very clever person, of the most advanced school of liberalism, and has married a rigid Catholic & Legitimist– She tells me that he bears with her much better than she bears with him–which is really a confession.”1 Blackett is the subject of an affectionate and elegiac tribute by Henry James which appeared in his 1903 volume William Wetmore Story and his friends. She is described by the author as “Of old Northumberland race, married to a Frenchman, then widowed, childless, and loving the world, of which she took an amused view” and fondly recalled for the “boundless extent of her acquaintance and the emphasis of her kindness to those she judged most in want of it.”2 An anecdote in the diary of Augustus Hare appears to be in keeping with her fearless liberality of spirit, if somewhat startling in its particulars:

“Dined with Madame du Quaire—her table like a glorious Van Huysum picture from the fruit and flower piece in the centre. The hostess is famous for the warmth and steadfastness of her friendships. Mrs. Stewart says—‘Fanny du Quaire is the only person I know who would do anything for her friends. If it were necessary for my peace that I should have poison, I should send for Fanny du Quaire, and she would give it me without flinching.”3

She was likewise the confidant to whom Robert Browning protested so vigorously when she stated a preference for his poetry over that of Elizabeth Browning:

“You are wrong—quite wrong—she has genius; I am only a painstaking fellow. Can't you imagine a clever sort of angel who plots and plans, and tries to build up something—he wants to make you see it as he sees it—shows you one point of view, carries you off to another, hammering into your head the thing he wants you to understand; and whilst this bother is going on God Almighty turns you off a little star—that's the difference between us. The true creative power is hers, not mine.”4

Group portrait including a woman identified as Frances Mary Blackett (seated); identified on the verso as “Cousin Robert Ingham with Frances Mary Blackett, (Unknown Female) & John F B Blackett -or- Montagu Blackett." Image courtesy of Jesse McKay.

Finally, she is the subject of a striking character sketch by the poet Marc-André Raffalovich (1864–1934), who, writing for the New Blackfriars in 1929 under the pseudonym “Alexander Michaelson,” recalled that “One liked to pretend that Fanny Blackett (sister of John Burgoyne Blackett, M. P. for Newcastle-on-Tyne) had invented marriage, widowhood, and Chevalier du Quaire, so as to be freer than a Victorian spinster. How comic to imagine that Madame du Quaire, tall, powerful, red haired, plain of speech, without any human respect whatever, needed widowhood to be free.”5

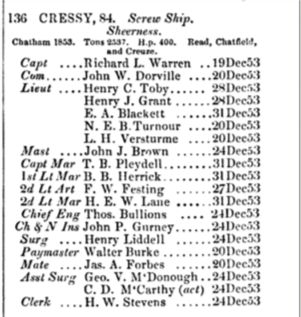

In 1853–1854, however, when the Morgan letters were written, Fanny Blackett was over thirty years of age and a spinster by popular reckoning. She was also, as her letters make clear, far from free. The same letters recounting her active participation in the cultural, political, and social life of London also include pointed expressions of frustration at the constraints constantly placed upon her by the familial authority of her brother John as well as an implied chorus of censorious relations. Blackett’s father had died, and her elder brother had assumed the title and replaced him officially as the head of the family. As an unmarried sister, Blackett was essentially his ward and financial dependent. Writing in one letter that her plans for an upcoming visit to Paris have been "knocked on the head," Blackett asks Madame Blaze de Bury if there is any "decent respectable sort of woman" with whom she might stay while there; adding that it cannot be a "pension" as "The idea of my going to a pension wd. set all my people screaming," and they would "very likely shut me up in a mad house." She enjoins her friend not to tell anyone of her intentions, as her family might get wind of it and "set upon him and say that the idea was utterly monstrous.”6

Reproduction of an engraved portrait of Frances (“Fanny”) Blackett’s elder brother, John Fenwick Burgoyne Blackett, 1852 (Newcastle Libraries, Newcastle upon Tyne, England, accessed through Flickr)

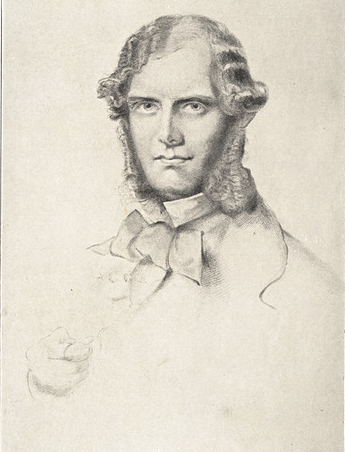

Several of the letters from Blackett to Blaze de Bury concern the German pianist Ernst Haberbier, who toured widely during this time period and visited London in 1854. Blaze de Bury had evidently recommended him as a protegee to her friend, and Blackett’s letters recount her ongoing efforts to introduce him into London society and assist him in procuring professional engagements. Over time however, the letters chronicle Blackett’s growing impatience with the musician and her increasing skepticism regarding his intentions, as she reports his repeated appeals for money coupled with his habitual refusal to perform for potential patrons. Worse still, Haberbier’s general lack of discretion and integrity in financial matters served to make him a social liability of the kind that Blackett, as a single woman, could ill afford. Finally, fed up with his “extraordinary mendacity,” she informs Blaze de Bury of her resolve to sever the connection, explaining her position with:

“I would do so if I were a free woman but I am not—the fact is that I have a good deal more liberty than most people of my age who are unmarried but there are some things wh. I cannot do—I told you the sort of prejudice my people have against artists—I sh. get into an irremediable scrape with all of them my brother at the head if I were to see much of him"7

A few years later, as Fanny du Quaire, Blackett would gain her freedom and the right to openly consort with the artistic and literary circles of London and Paris.

Portrait of German pianist and composer Ernst Haberbier (Bergen Public Library Norway, accessed through Flickr)

Fanny du Quaire (nee Blackett) is only one of a varied and cosmopolitan network of female correspondents represented in the collected letters of Rose Blaze de Bury. With the exception of the letters themselves, however, there is little to be learned of her life before her marriage. It is largely through her relationships with her male relatives, friends, and associates that any information about her may be gleaned from available sources, and the results yield only a fragmented if intriguing picture. It was, after all, the first name of her brother and his profession as a naval officer that allowed me to establish her identity. The general exclusion of women from the professional, political, and academic sphere and, by extension, from related bodies of published and archival documentation, limits the sources available for studying women’s lives. As previously noted, Rose Blaze de Bury is herself a neglected subject, and despite the exceptional scope of her achievements as a writer, her reputation quickly lapsed into obscurity following her death in 1894. No biographical studies, collection of published correspondence, or in-depth considerations of her life and work appeared over the course of the twentieth century. It wasn’t until the twenty-first century that a study dedicated to Blaze de Bury’s life and work appeared in the form of a dissertation by historian Rachel Egloff entitled, A study of the life and works of Blaze de Bury : a counter-narrative of a transcultural woman's involvement in nineteenth-century European politics.

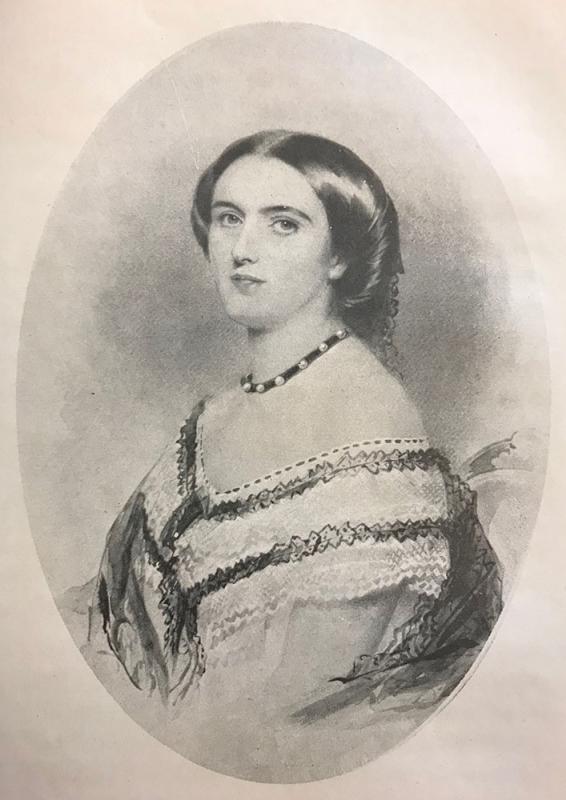

Reproduction of a watercolor portrait of Baronne Rose Blaze de Bury (Pailleron, Marie-Louise. Les derniers romantiques. Paris: Perrin, 1923, facing page 192)

In her chapter describing Blaze de Bury’s life in Europe and political connections, Egloff addresses the methodological challenges inherent in studying women’s engagement in nineteenth-century political and intellectual life. In particular, she notes the lack of available resources for studying social networks of female correspondents, whose activities and relationships might contribute to our understanding of the subject. She notes that Blaze de Bury’s own correspondence survives in a scattered and fragmented form, often preserved in collections of letters of more prominent individuals, and that her study treats “only a sample of individual network-links.” As she explains:

“A potential consequence of this is the lack of women represented in Blaze’s network. Many women writers were written out of the canon by what Michel Foucault called ‘rules of exclusion’. We assume that Blaze corresponded with more women than are currently canonised or can be traced. This gap is widened by the lack of information about some of her female acquaintances. Because women generally lacked an official profession and their status was usually dependent on their male family members, women’s estates, like Blaze’s, tended to be fragmented, lost, or to remain uncatalogued.”8

Exclusion tends to beget exclusion. Lack of available primary sources stymies research and leads to gaps in the secondary literature that might otherwise inspire or inform the work of current researchers. This absence of a foundation in the form of available scholarship means that the researcher interested in establishing the facts of a subject’s life must resort to original research, locating and pulling together information from a range of scattered available sources. Of course, these are challenges familiar to any researcher intent on locating information on members of any social group who have been systematically excluded from or underrepresented in the traditional historical record. The fact that members of Blaze de Bury’s circle proved difficult to document should invite us to consider how daunting it may be to study the lives of women who lived in less privileged circumstances and who are often more difficult to research and resurrect from obscurity and neglect.

Catalogers inhibited by time constraints and production quotas may be compelled to perpetuate the longstanding neglect of unstudied subjects. Under pressure to meet workplace expectations, they may be unable to perform the remedial “ground up” research necessary to identify an obscure subject or create a useful description of an item that includes even the basic elements of an individual’s biography. The preliminary work required to puzzle through letters and documents by unidentified individuals inevitably adds to the time required to catalog them. Available historical documentation for many women, even the educated and comparatively affluent women like those who Blaze de Bury counted among her correspondents, tends to be limited in comparison to that available for men of comparable socio-economic status. Consequently, letters and manuscripts by and about women frequently demand a greater investment of time to catalog at a level comparable to that of their male peers.

As a cataloger at the Morgan, I have been part of a larger initiative aimed at critically re-evaluating our collection descriptions and improving access to rare and unique materials relating to the history of marginalized and underdocumented cultures and social groups. It is an ongoing and concerted effort that has proven both challenging and rewarding, and it is my own hope that efforts like ours may, in time, contribute to a knowledge and recognition of those who have been too long forgotten or systematically excluded from our historical consciousness.

Sandra Carpenter

Gordon Ray Cataloger

Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Sarianna Browning, [letter postmarked 5 November 1857]. In The Brownings’ correspondence (Winfield, Kansas: Wedgestone Press, 1984-), volume 24, 203–205

- James, Henry. William Wetmore Story and his friends: from letters, diaries, and recollections (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1903), 120–122

- Hare, Augustus John Cuthbert. The story of my life (London: George Allen, 1896–1900), volume 3, 566

- Orr, Alexandra, et al. Life and letters of Robert Browning (London: Smith, Elder, & Co, 1891), 355

- Michaelson, Alexander. “Parallels.” Blackfriars 10 (1929), 780

- Frances Mary Blackett du Quaire (1822–1895) Letter to Baroness Marie Blaze de Bury, London, 1853 August 21. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987. MA 14300.131

- Frances Mary Blackett du Quaire (1822–1895) Letter to Baroness Marie Blaze de Bury, London, [1853]. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987. MA 14300.139

- Egloff, Rachel. “A Study of the Life and Works of Blaze de Bury: A Counter-Narrative of a Transcultural Woman’s Involvement in Nineteenth-Century European Politics” PhD diss. Oxford Brookes University, 2020, 65