Fig. 1. Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). The Picture of Dorian Gray. First page of the autograph manuscript [1889–90]. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1913; MA 883.11.

Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fézensac was the arch-aesthete of the Decadent era. Titled, rich, perfectly groomed, and exquisitely attired, he turned himself into a work of art as precious as the poetry he composed and the bibelots he collected. He was a model for the Des Esseintes and Baron de Charlus characters in À rebours and À la recherche du temps perdu. Oscar Wilde emulated his eccentricities in The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which the title character is corrupted by reading À rebours. The Morgan’s manuscript of that work (fig. 1) shows how Wilde set the scene for this moral parable, which includes perfervid descriptions of the Decadent lifestyle..

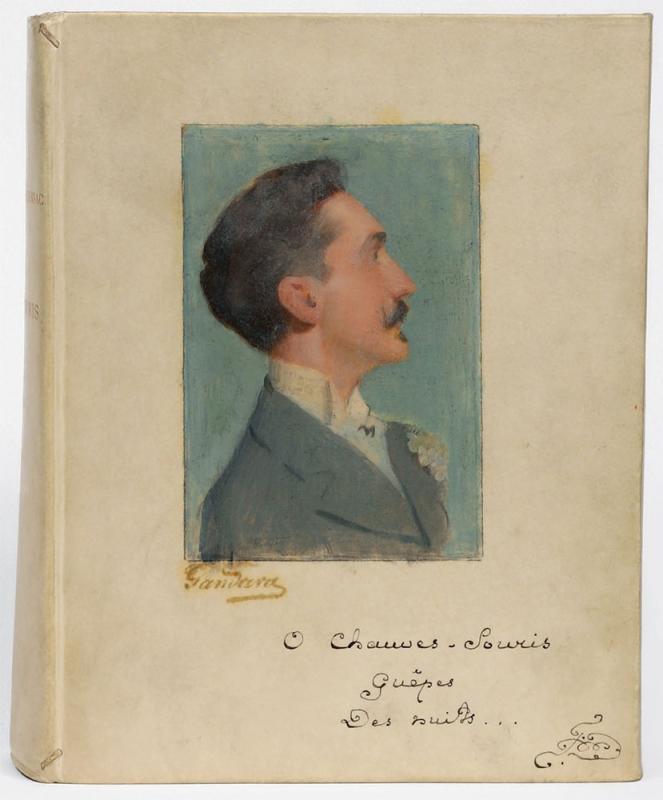

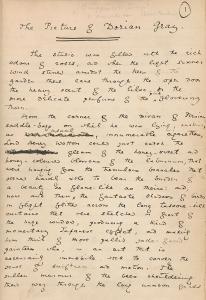

Montesquiou looked the part, a dandy personified in portraits by Whistler, W. Graham Robertson, and Antonio de La Gándara. He was at the height of his fame when Robertson made this drawing of him (fig. 2) in a studiously affected pose designed to display to best effect his elegant outfit and sinister expression. Robertson visited him in Paris and greatly admired the way he had furnished his apartment, “like a vague dream of the Arabian nights translated into Japanese.” Perhaps this drawing was made on that occasion.

The Gándara portrait is even more revealing (fig. 3). The Morgan obtained it last year when it bought a copy of Montesquiou’s Les chauves-souris at auction. This large quarto collection of his poetry gets its title from the bat motif he took as his personal emblem: it figures in the silk doublures of some copies and in the watermarks of a hundred fine-paper copies intended for presentation to friends and colleagues. He gave this one to the critic and collector Edmond de Goncourt, who commissioned Gándara to paint a portrait of the author on the front cover of the binding.

Between 1890 and 1896, Goncourt built a collection of twenty-nine portrait bindings executed by his favorite artists such as Renoir, Rodin, Chéret, Bracquemond, and Tissot. Some did their work in watercolor, others in oil, and Renoir delivered his on a canvas, which had to be fastened to the binding. Zola, Mirbeau, Daudet, and Huysmans were among the authors immortalized in his collection. Each of the books was on special paper, and most of them contained an autograph manuscript. Goncourt made a special effort to enhance the association value of his pictorial Les chauves-souris: he inserted a dedicatory letter by the author and had him write a quotation on the front cover followed by a bat-motif monogram. The collector put his mark on the book by having his monogram stamped in gilt on the back cover and by writing an account of the portrait on a flyleaf. If that was not enough, later owners of the Morgan’s copy of Montesquiou’s Les chauves-souris laid in engraved portraits of Montesquiou after Whistler and a four-page autograph letter the poet wrote to the society hostess Léontine Charlotte Arman de Caillavet. This personalizing process set a trend in book collecting still prevalent in France but also evident wherever book lovers have learned about the powers of provenance.

Fig. 4. John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). Dr. Pozzi at Home, 1881. Oil on canvas. 79 3/8 x 40 1/4 in. (201.6 x 102.2 cm). The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

The Morgan has another copy of Les chauves-souris presented to the celebrity physician Samuel Pozzi. Why do we need two copies? By noting provenance, we can use them to chart intertwining connections in the cultural elite at the turn of the century. Famous in his own day as a pioneering gynecologist, Dr. Pozzi is best known now for John Singer Sargent’s portrait of him (fig. 4) in that unforgettable crimson dressing gown. Sargent introduced Montesquiou to Henry James who introduced him to Whistler who painted him with a chinchilla cape that belonged to the great beauty and clothes horse Comtesse Greffulhe. Montesquiou owned a sketch of one of Greffulhe’s outstanding attributes, her chin, executed by Gándara. Both Gándara and Sargent painted portraits of another Parisian beauty, Virginia Gautreau, otherwise known as Madame X. One of her lovers was Dr. Pozzi, who introduced her to Sargent. More connections could be cited, and many of them lead back to Montesquiou, a central figure in literary circles and the art world at the turn of the century.

John Bidwell

Astor Curator and Department Head

Printed Books & Bindings

The Morgan Library & Museum