Figure 1: Peter Burra.

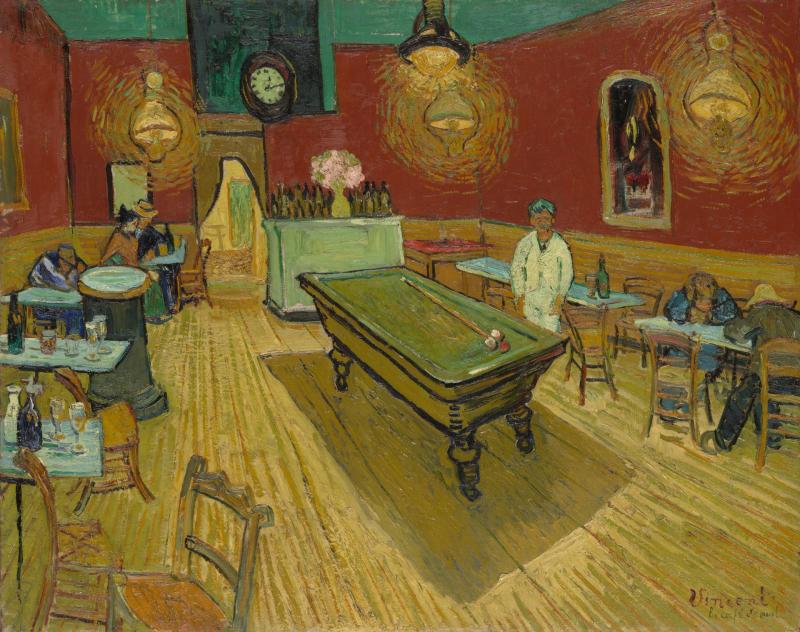

Figure 2: Letter from Van Gogh to Bernard, June 19, 1888, with sketches of Wheatfield with the Setting Sun and the leg of his easel staked to the ground. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, MA 6441.7.

Douglas Cooper’s acclaimed 1938 translation of Vincent van Gogh’s Letters to Émile Bernard owes a debt to the uncompleted work of author and critic, Peter Burra, who died in a flying accident in April 1937 (Figure 1). Intended or not, Cooper (writing under the pseudonym Douglas Lord) failed to acknowledge the work that Burra had already undertaken on the Bernard Letters with the result that his contribution to Van Gogh scholarship has been overlooked (Figure 2).

Burra was only twenty-seven when he died. In a memorial tribute, E. M. Forster described him as “the best critic of his generation” and wrote further, “had he lived he would certainly have won fame as a creative artist too, his most important publications [being] his books on Van Gogh and on Wordsworth.”1

Such praise from an author of Forster’s stature reflects the high regard in which Burra was held during the 1930s. The painter, A. S. Hartrick, whom Burra met in 1933 to discuss his personal recollections of Van Gogh in France, wrote how “truly grieved” he was on receiving the news, adding, “I was much interested in his views on art and think his small “life of Van Gogh” much the best account of that much discussed artist that has appeared.”2

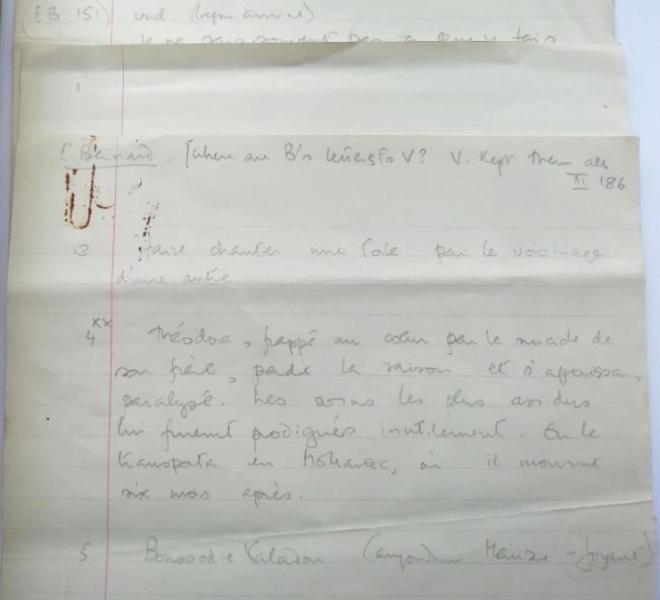

In a letter of condolence to Burra’s mother, Douglas Cooper, the twenty-six-year-old art collector wrote (Figure 3): “I am most terribly sorry to read the sad news of Peter’s sudden end. Having been out of the country for six months I have not seen him since I spent a week at Foxhold in November [1936]. But I kept up a long correspondence with him during my absence and indeed have been working for him in the U.S.A. on the subject of Van Gogh, the results of which I never even had time to tell him about.”3

Sadly, that correspondence is missing, believed destroyed when Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears cleared “sensitive material” (without permission) belonging to Burra at Foxhold, the cottage in which he was living at the time of the accident.4 As young gay men, they had reason to fear the consequences of such material falling into the wrong hands given the harsh indecency legislation in force in Britain at the time.

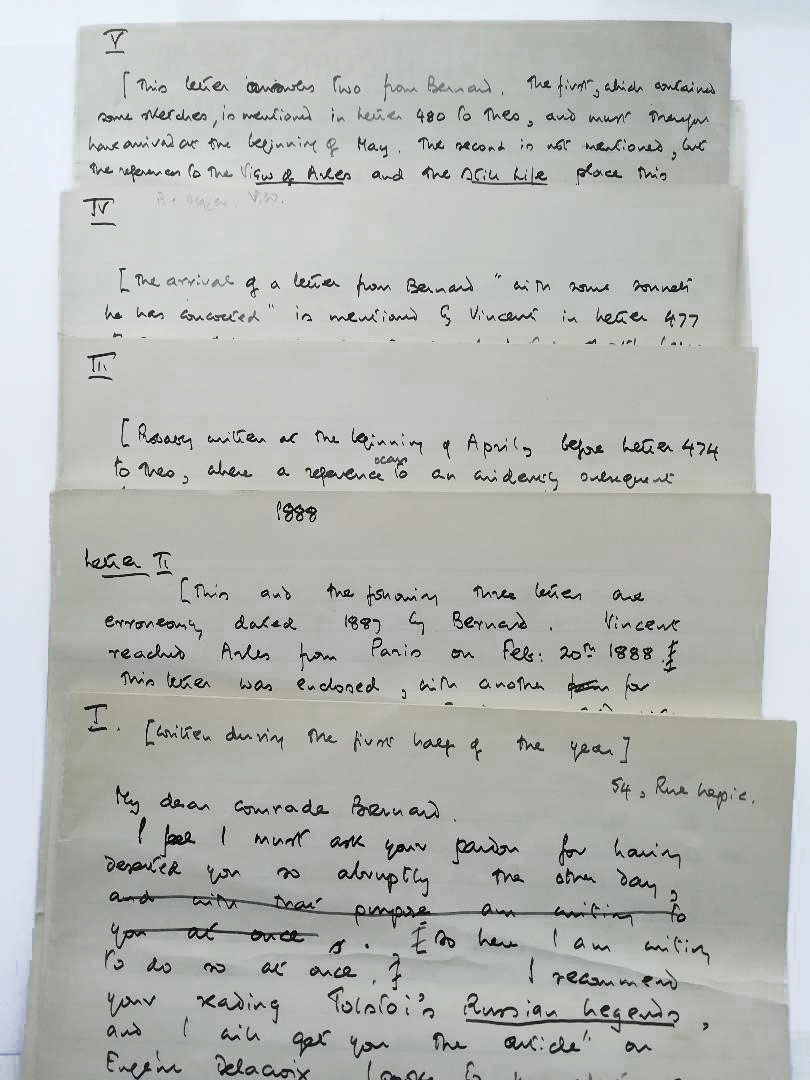

In July 1938, fifteen months after Burra’s tragic death, his mother received a large buff envelope containing numerous handwritten pages of her son’s translations of letters that Vincent van Gogh had written to his fellow artist and friend, Émile Bernard (Figure 4). She knew that the translations had been made from the Lettres de Vincent van Gogh à Émile Bernard, published by Ambroise Vollard in 1911,5 but not that Cooper had been in possession of them since the end of 1936. She was also unaware that he was returning them shortly before the publication of his own 1938 English language version of the letters entitled: Van Gogh, Letters to Émile Bernard.6

Figure 3: Douglas Cooper’s letter of condolence to Ella Burra, 5 January 1937.

Figure 4: The buff envelope containing Burra’s translations from Vollard, which Cooper returned to Ella Burra in July 1938. Her handwritten note in pencil, “4 Bernard letters Translated,” should have read “5.”

An Unlikely Partnership

Douglas Cooper and Peter Burra were both precociously talented, sharing a taste for European art and culture and an admiration for great artists like Van Gogh and Picasso who flouted convention. Unlike Burra, Cooper was wealthy, having inherited a substantial fortune at the age of twenty-one, and able to indulge his passion for collecting Cubist works of art. Described as “fiendish” funny, and outrageous,7 he could afford to travel first class to America on the great transatlantic liners.

By comparison, Burra was a struggling writer and critic, albeit with a growing reputation, who relied on newspaper editors to pay his expenses while travelling around Europe. Described as “charming, sensitive [with] a discerning and fastidious mind,”8 his biographies of Van Gogh and Wordsworth9 reflect his identification with artists and writers for whom life and creativity are inextricably linked.

‘Impressionism’ in the Letters of Van Gogh (1932)

It was while Burra was writing for The Times in Germany in 1932 that he became interested in the notorious Wacker “fakes trial” taking place in Berlin. Art dealer Otto Wacker stood accused of passing thirty fake Van Gogh paintings onto the open market.10 In December that year, he was found guilty of fraud. His conviction seriously embarrassed a number of leading art experts including J. B. de la Faille, editor of the 1928 catalogue raisonné of Van Gogh’s works.

Burra wondered how these experts could have been duped by Wacker given their intimate knowledge of the paintings and the availability, since 1927, of the extraordinarily detailed letters that Van Gogh had written to his brother, Theo. It seemed to Burra that the letters gave a unique insight into the mind of the painter as he was creating his works. The words, in other words, were as much part of Vincent’s signature as the paint.

In the autumn of 1932, he wrote an article (or essay) entitled Impressionism in the Letters of Van Gogh in which he expressed the view that:

The most interesting documents in the history of the later stages of Impressionism are the letters of Vincent Van Gogh, which are published in three volumes by Mssrs. Constable and Company… Van Gogh’s letters are the most wonderful literary performances in the history of Art, and their magnificence in poetry and sentiment has quite obscured their interest with regard to Vincent’s own pictures and the general progress of Impressionism… Modern historians number him with Gaugin (sic) and others as one of those who did most to complete Impressionism, bring it to an end and take painting somewhat further. Stated thus, it sounds as if this was his conscious aim. The letters show exactly how the progression of events really seemed to him.11

In this article Burra makes no mention of the letters from Van Gogh to Émile Bernard, which suggests that he was not yet acquainted with them. However, his personal archive still holds the four-volume set of de la Faille’s 1928 catalogue raisonné and Johanna van Gogh-Bonger’s three English language volumes of The Letters of Vincent van Gogh to His Brother, which he used throughout the time he was writing about Van Gogh.

The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh (1932)

Inspired by his reading of the Vincent-Theo letters, Burra now wrote an extended essay entitled The Letters of Vincent van Gogh in which he sought to explain why art was Vincent’s life:

The pictures that he describes in words are dazzlingly vivid. He saw Nature as none had ever seen her before… He saw almost visibly the fertility in the trees, the sap in the flowers, the moments of growth and the riots of life. He saw the link of that life with the life of man… Who else could have written words like these, words that reproduce exactly the effect of his paint… The success of Van Gogh as a painter lies in this: that he conveys to us exactly what we know from his letters that he wished to convey: “the thing represented” was “absolutely in agreement and one with the manner of representing;” and “the thing represented was the life in living things.12

Keep in mind that Burra was writing ninety years ago when Van Gogh scholarship was in its infancy. Even then he saw the letters as central to recognizing Vincent’s unique identity in the paintings. It was in this essay that he first quotes from a letter by Van Gogh to Émile Bernard concerning Gaugin’s Christ in the Garden of Olives, where Vincent states: “One can give the impression of fear without going direct to the historical Gethsemene and one can paint a comforting and gentle subject without depicting the chief actors in the Sermon on the Mount.”

This translation from the French is from Letter XXI in the 1911 Vollard edition of Lettres de Vincent van Gogh à Émile Bernard.13 Burra’s detailed handwritten notes show that he worked through the book translating relevant passages as he went along. It is these notes that date his initial translations of the letters to 1932–3 (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Burra’s 1932/3 handwritten page-by-page translation notes from Vollard 1911. Note the reminder to himself to find out where Bernard’s letters to Vincent are.

Making use of both the letters to Theo and the letters to Bernard, he began cross-referencing them to clarify the dates on which they were written. On reading the postscript to Letter 538 in J. vG-Bonger III, where Vincent tells Theo: “I am keeping all Bernard’s letters… there is quite a bundle already,”14 he wrote a note to himself: “Where are B’s letters to V? V. kept them all. III 186’.”15

Whether he intended to publish this essay in a journal is unclear, but his archival papers show that he submitted it to Duckworth publishers at the end of 1932 as a proposal for a book he intended to write. George Milsted, a director of the company, recommended it to his fellow directors saying:

I have talked to Burra & he sends a short study he had already done of Van Gogh… He would like to expand it, re-write it & alter its construction & make 35,000 words of it, or more. The subject is one in which he is enthusiastic & he wants to do the life-story, with quotations from the letters (which only a few people read in an expensive publication); his own ideas & interpretation of the subject’s significance, & not too much technical talk about paint.16

Burra’s Van Gogh (1934)

The book, simply entitled Van Gogh, was commissioned on 20 February 1933 and scheduled for inclusion in Duckworth’s biographical Great Lives series the following year. Burra wasted no time in contacting key personnel and assembling source materials for his research work, which he planned to carry out in Holland and Belgium between May and June 1933. In preparation, he read Elizabeth Duquesne van Gogh’s Personal Recollections of Vincent van Gogh (1913), Julius Maier-Graefe’s Vincent: A Life of Vincent van Gogh (1922), Gustave Coquiot’s Vincent van Gogh (1923), Louis Pierard’s The Tragic Life of Vincent van Gogh (1925), Paul Colin’s Van Gogh (1926) and, on meeting A. S. Hartrick, read his privately printed recollections of Van Gogh in Post Impressionism (1916).17

In May he wrote to V. W. van Gogh, the painter’s nephew, asking him if he still held the letters from Émile Bernard to Vincent, perhaps expecting to meet when he was in Amsterdam.18 Once in Holland, he visited Breda, Etten, and other towns and villages in which Vincent had lived. He spent time in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and found the Van Gogh collection “thrilling.” After a further six days in the Hague, he moved on to “villages in the south before going to Antwerp.”

On his return to England in June, he settled down to write his biography, using the V G-Bonger and Vollard volumes as primary sources. Evidence of his translations from Vollard can be found throughout his original typescript. An example is the reference to the Café de Nuit on page 85, where he writes (Figure 6):

[Vincent] was fascinated with ideas about night painting, and experimented with the ways of expressing starlight, or the gas-flares of the Cafés. He spent three whole nights in the famous “Café de Nuit”, which he assured Bernard, was not a brothel, but simply a café where the night-wanderers ceased to be night-wanderers by stretching themselves out on the tables.19.

This derives from Letter XVII of Vollard: “Il y a que je t’ai déjà écrit mille fois que mon café de nuit n’est pas un b[ordel], c’est un café où les rôdeurs de nuit cessant d’être des rôdeurs de nuit, puisque, avachis sur les tables, ils passent là toute la nuit sans rôder du tout”.20

The assurance to Bernard about the café not being a brothel does not appear in a similarly expressed passage in Letter 518 from Vincent to Theo: “It is what they call here a Café de Nuit (they are fairly frequent here), staying open all night. Night prowlers can take refuge there when they have no money to pay for a lodging, or are too tight to be taken to one.’”21

Burra submitted his biography to his publishers in August 1933. Three months later, he received the long-awaited reply from V. W. van Gogh saying: “It is not through unkindness that I did not reply to your letters… my wife having died in the end of August. I have been looking if I do have letters by Bernard to Vincent, but did not find any yet. However, I will soon see again amongst another bunch of letter[s] where there might be some; if so, I will let you know.’”22

When Van Gogh was published in March 1934, Burra sent a signed copy to V. W. van Gogh, who thanked him for the book but made no mention of the Bernard-Vincent letters.23

Douglas Cooper

The success of Van Gogh significantly raised Burra’s profile, though not his income. The constant demands of journalism clashed with his work as a creative writer. His archive shows that between 1934 and 1936, while writing his biography of Wordsworth, he was fully engaged as a literary, drama, and music critic, which left him little time to further his interest in the Van Gogh letters.

It is not clear exactly when Burra met the young Douglas Cooper, but in all probability it was at the much-vaunted Surrealist exhibition in London on 19 June 1936. A month later he received a postcard from Cooper, showing the Romanesque cloister of Saint-Paul de Mausolé in St Remy, saying: “This cloister in which Vincent lingered, brings naturally the tenderest thoughts of you to my mind… I trust your summer proves successful. Arles is heavenly and the sun giving new life. D.C.”24

By now Burra was regarded as an authority on the Van Gogh correspondence. In October, the Times Literary Supplement published his review of Rela van Messel’s English translation of the Van Gogh-Van Rappard letters, which he considered “a rich mine for research,” though “carelessly assembled.”25 The following month, he wrote a longer review of the book for The Listener entitled The Taste of Van Gogh, in which he defended Van Gogh’s eclectic “disposition to be pleased.” by all he found good in art and true to the artist’s intentions.26

Figure 7: Burra’s translations of Letters 1 –5 from Vollard, 1911. Cooper used Burra’s five full translations and translation notes throughout the main text, as well as in the “Emendations to the Published text” and the bibliography.

It was during November 1936 that Cooper stayed for a week with Burra at his Berkshire cottage, which is when Burra must have given him his translations of the V G-Bernard letters (Figure 7). The question is why did he do this? Cooper was about to leave for America having agreed to undertake work on behalf of Burra while he was there. Without their “long” correspondence, one can only speculate as to what that actually meant in practice. What is known is that Burra was dissatisfied with the Vollard version of the letters. Editorial omissions limited their accuracy in translation from the French and having already translated the first five of these in full, he could see that there was a need to access the originals in order to correct deficiencies before continuing.27 From his perspective, it was a natural progression to produce a definitive version of the letters and, in Cooper, he had found the perfect person to assist him.

There is no evidence to suggest that Burra intended handing the translation project carte blanche to Cooper, though they may have agreed on some form of cooperation, or perhaps even joint authorship of the first English translation of the letters. Burra knew that the letters had passed into the ownership of the Baroness Marie-Anne von Goldschmidt-Rothschild in Berlin, which concerned him. His experience of Goebbels’ Kulturkampf in Germany warned of the danger of them falling into the hands of the Nazis. If they were at one of her private residences in Europe, they needed to be photographed to provide a facsimile record of their existence. This would then enable a new—and complete—set of the letters to be made in translation.28

A surviving postcard from Cooper dated 21 January 1937, written from the Hotel Barbizon Plaza, New York, reads: “Van Gogh has reopened here again, but only for a week. It’s a good opportunity of seeing several I haven’t seen before… Love D.C.’”