Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, artistic techniques, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators.

To coincide with an exhibition on view this summer in the galleries, J. Pierpont Morgan's Library: Building the Bookman's Paradise, the current East Room installation of Collections Spotlight focuses on examples of Morgan’s major acquisitions leading up to the construction and decoration of the historic building. In the Rotunda is a special presentation, Inside the Bookman’s Paradise, which features preliminary drawings and elevations by Alessandro Marcocchia, August Reuling, and H. Siddons Mowbray for the library’s interiors.

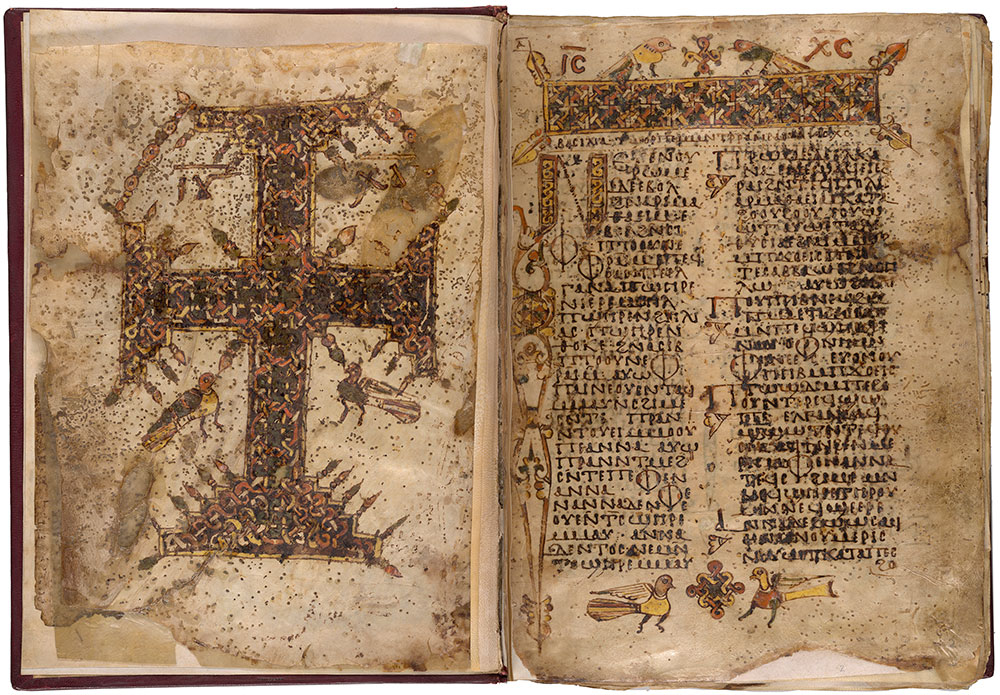

A Manuscript from Egypt

This manuscript, containing the Old Testament book of Samuel, is among sixty Coptic manuscripts acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan. The Copts were native Egyptians who played an important role in the history of Christianity and greatly contributed to the development of monasticism. The precious volumes purchased by Morgan once belonged to the Monastery of St. Michael in the Fayum district of Egypt (south of Cairo) and were discovered in 1910 in nearby Hamouli. Embellished with a cross frontispiece, this manuscript contains a note, dated 893 c.e., which states that it was a gift to the monastery. Further notes reveal the names of the scribes, Apaiouli and Isak.

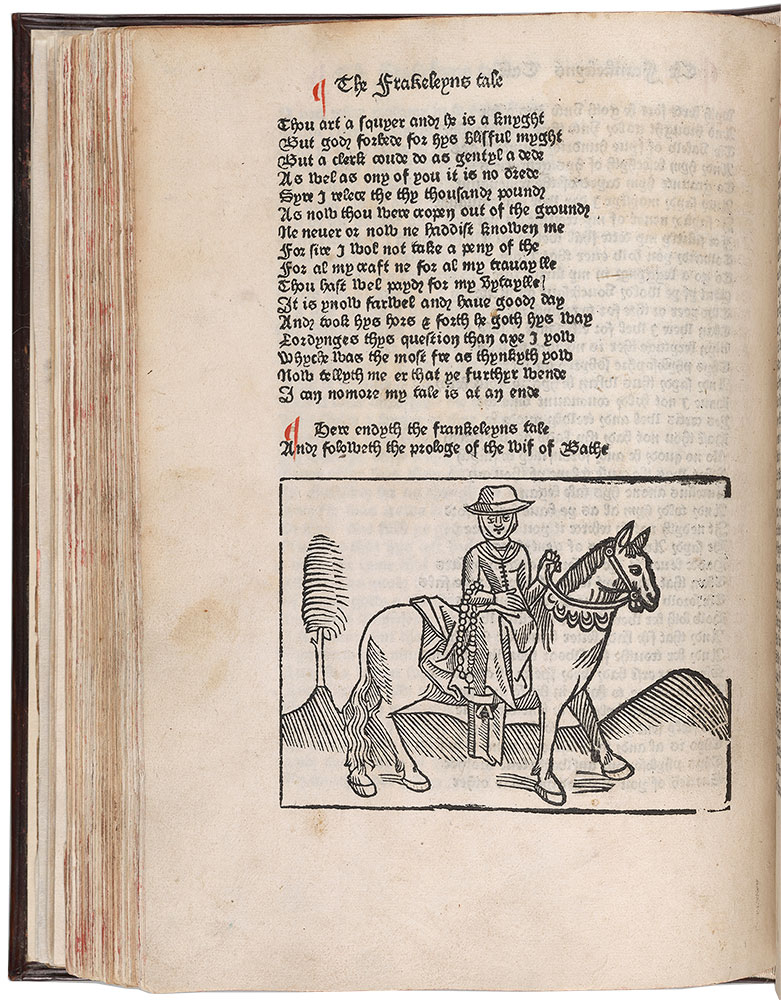

Printing on the Ceiling

In 1476 William Caxton published the first edition of The Canterbury Tales, perhaps the first English book printed in England. For this second edition, he added illustrations of each of the pilgrims that Chaucer described in the narrative, including this image of the Wife of Bath. In building his book collection, J. Pierpont Morgan specifically sought out works that Caxton printed, acquiring twenty-seven of his publications with the purchase of Richard Bennett’s library in 1902. Around 1904, Morgan instructed H. Siddons Mowbray, who was commissioned to paint the ceiling of the library’s East Room, to exchange the portrait of German printer Johann Gutenberg for one of Caxton. Visitors can see Caxton portrayed in the upper-right lunette above the main door.

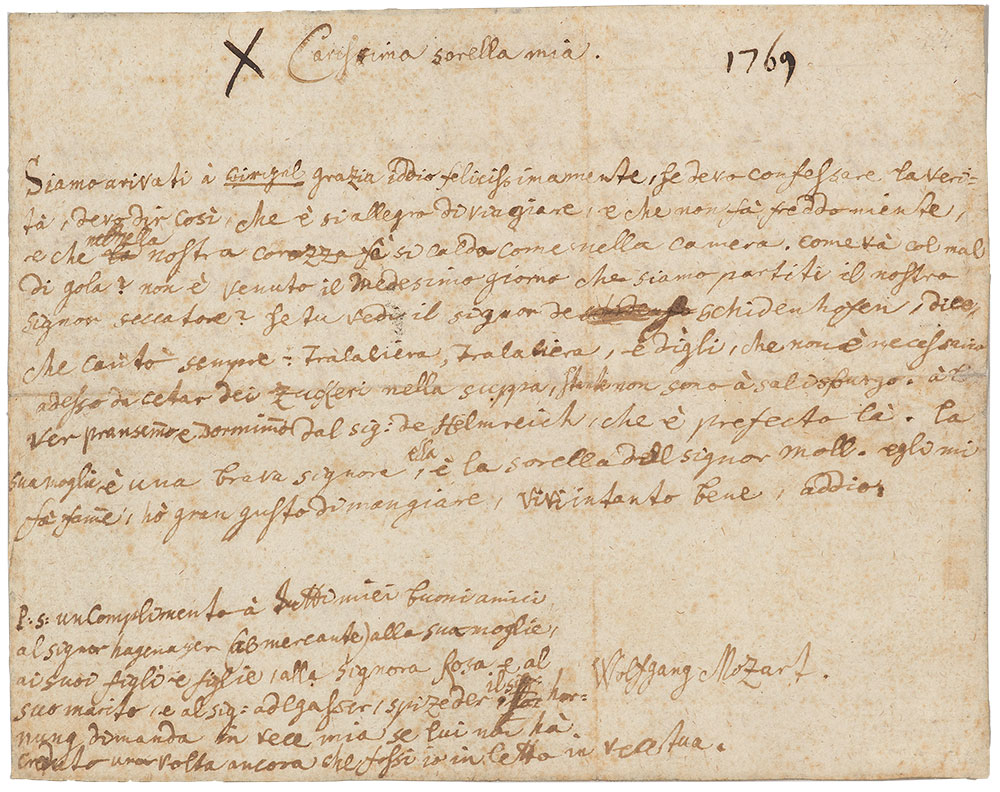

One of Mozart’s Earliest Surviving Letters Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his father, Leopold, left Salzburg for their first visit to Italy on 13 December 1769. The following day Leopold wrote to his wife about their trip, and the thirteen-year-old Wolfgang added a postscript. On the verso of this letter is an additional note by Wolfgang, this one addressed to Nannerl, his sister, and written in Italian. He asks after her health, inquires about friends, and tells her how he is enjoying the journey. In March Wolfgang would secure a commission to write an opera for Milan, Mitridate, rè di Ponto, which postponed their return home until well after the work’s successful premiere in December 1770. They arrived back in Salzburg in March 1771.

A Favorite Bookseller

The Benedictine Psalter was the second dated book from the Mainz printing shop of Johann Fust (Johann Gutenberg’s former partner) and Peter Schoeffer. All surviving copies are on vellum. When the London bookseller Bernard Quaritch acquired this copy at auction in 1884, it was the highest price ever paid for a printed book. He had difficulty reselling it, however: it wasn’t purchased until 1900, when J. Pierpont Morgan began to patronize Quaritch’s shop (then run by the bookseller’s son, Bernard Albert). The Psalter, significantly reduced in price, was one of twenty-one volumes Morgan acquired on a single day.

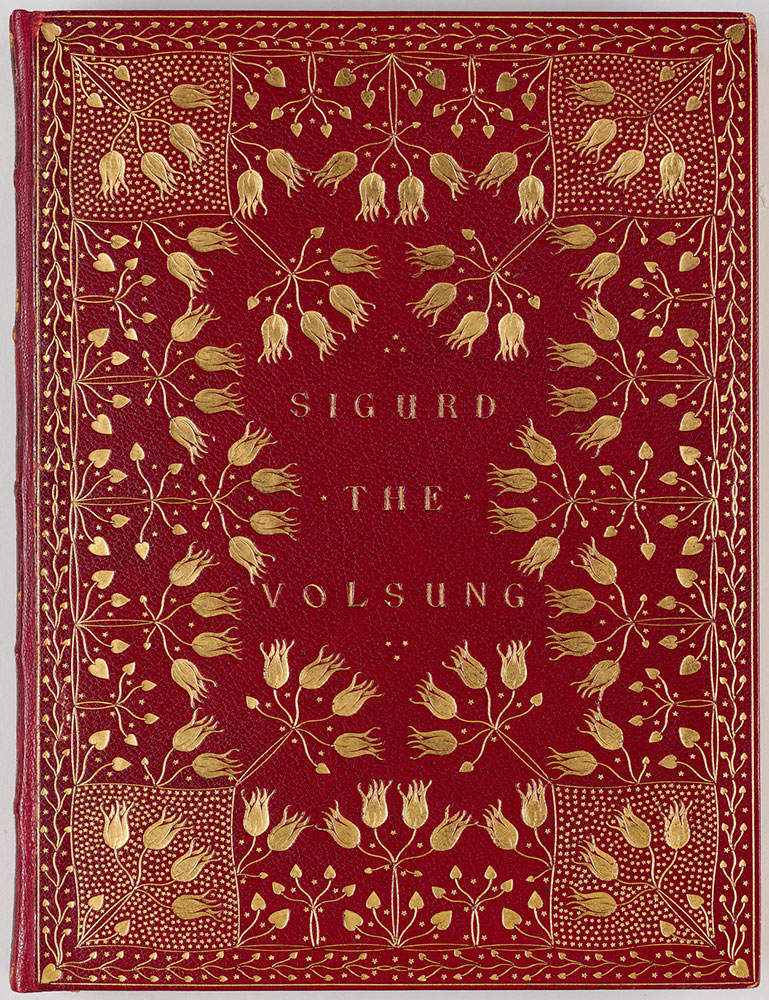

From Barrister to Binder

The revival of fine printing in the late nineteenth century was part of the Arts and Crafts movement, spearheaded in England by the writer and artist William Morris. The movement privileged hand production in the decorative arts in response to increasing industrialization. A key figure in Morris’s circle was Cobden-Sanderson, who abandoned a legal career in the 1880s to take up bookbinding. His delicate floral patterns, exemplified by this copy of Morris’s epic poem, revolutionized the aesthetic of bookbinding. By 1893 Cobden-Sanderson had established his own workshop, the Doves Bindery, which was closely allied to Morris’s Kelmscott Press.

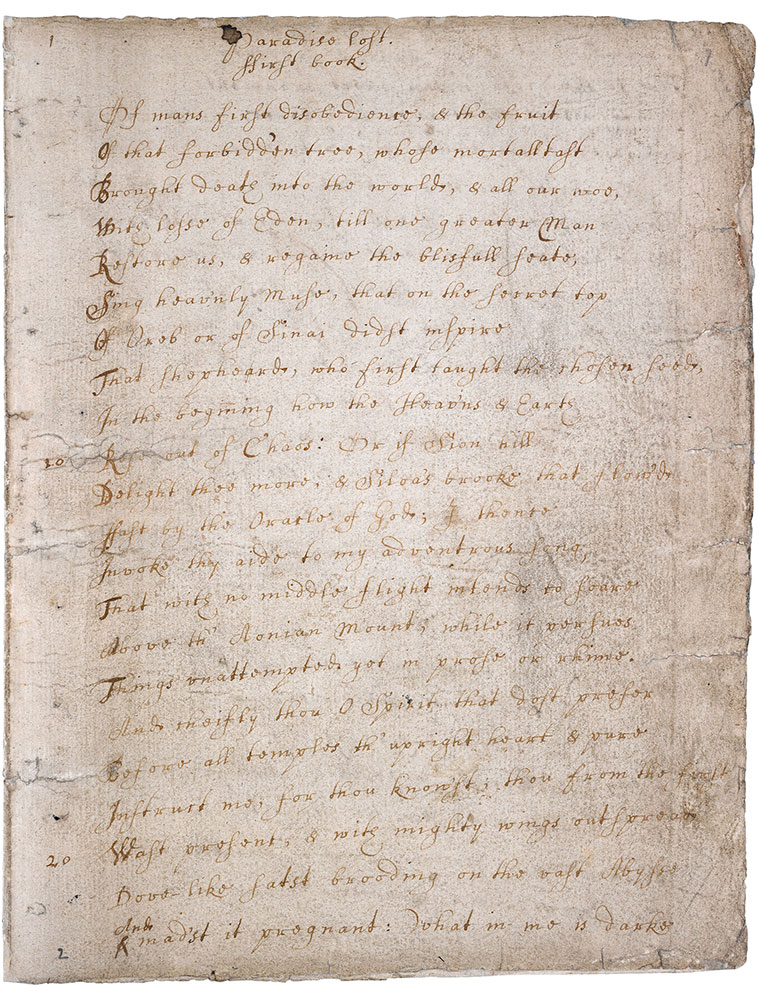

Things Unattempted Yet

This is the only surviving fragment of the manuscript used to print Paradise Lost, Milton’s epic poem of the Edenic fall. Driven to achieve “things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme,” Milton adopted innovative thematic and formal approaches, sourcing his characters from the Bible (rather than British history) and composing his lines in blank verse instead of heroic couplets, which were more fashionable at the time. The final words on this page—“what in me is darke / [Illumine]”—allude to the ocular troubles that had left Milton blind in the 1650s. This fair copy of the poem’s first book was transcribed by an amanuensis (literary secretary) and bears further annotations by the printer and compositors.

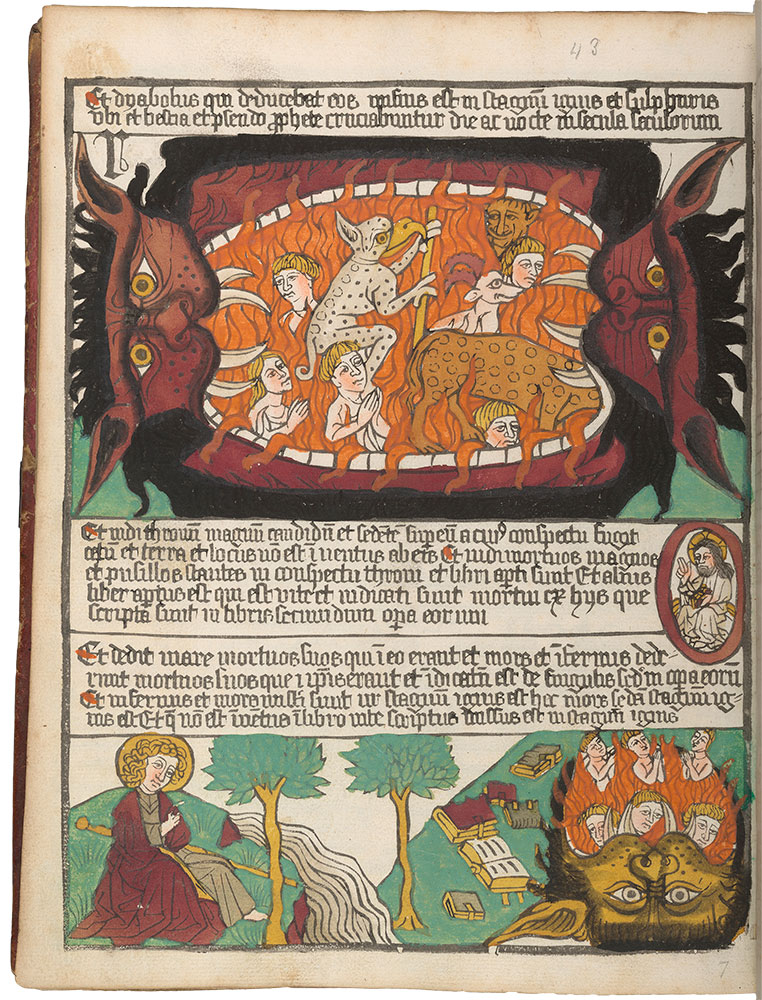

Competition for Gutenberg

When Johann Gutenberg was developing typographic printing in Mainz, competitors were producing volumes entirely from woodcut, now known as blockbooks. This blockbook presents the book of Revelation (Apocalypse) in the Christian New Testament. Shown here is an image of demons in hell, represented by the giant animal mouth, while St. John, Revelation’s author, looks on from below describing his vision. The original buyer could have purchased this book in two formats: either with image pages facing each other or with each image facing a blank, as here, likely intended for manuscript notes or commentary on the illustration.

The Art of the Book

An inscription on the first leaf of this Gospel lectionary states that it was written in 1436 for Pietro Donato, bishop of Padua. An ardent bibliophile and patron of the arts, Donato commissioned Peronet Lamy, a French painter active at the ducal court of Savoy, to create the miniature of the Nativity shown on the left. The miniature on the right, painted by an anonymous Paduan artist, illustrates a passage from Luke’s Gospel in which the emperor Augustus orders a census of the world. Fifty-two miniatures, the work of this same Italian hand, complete the decorative program. Both the miniatures and the distinguished provenance would have appealed to J. Pierpont Morgan, who had only started to build his manuscript collection when he bought the volume.

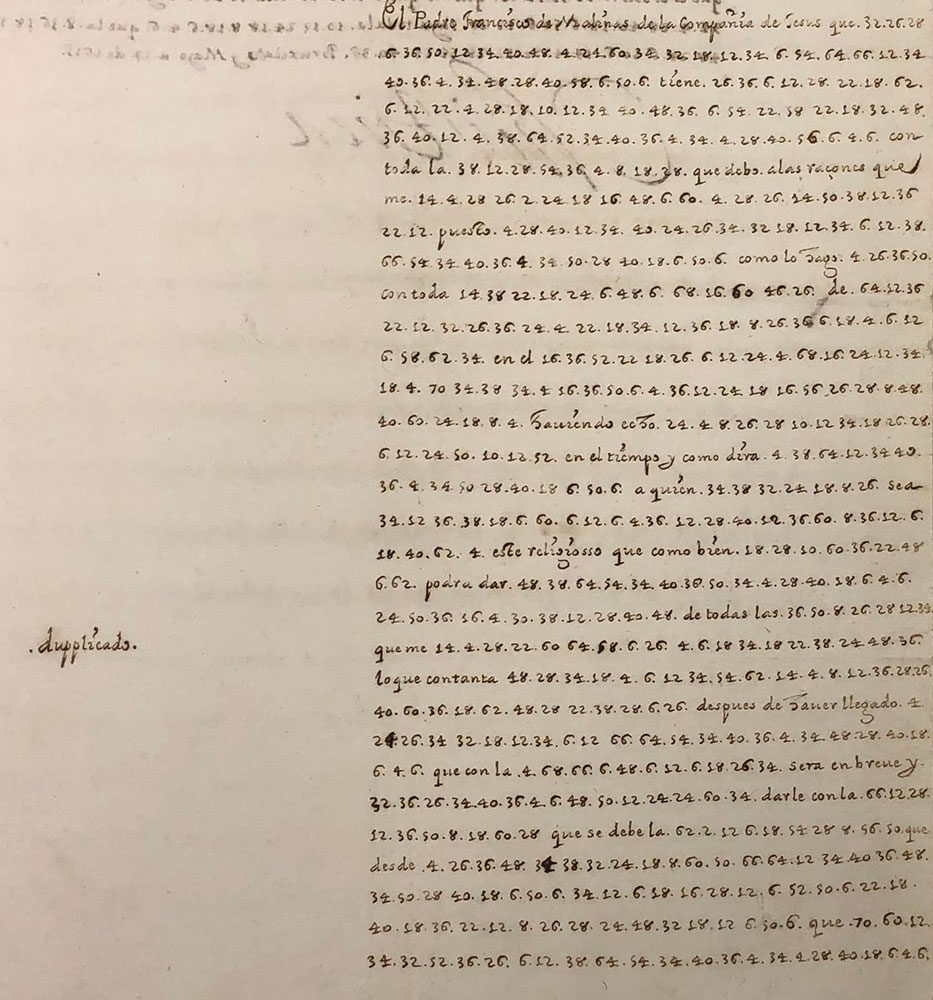

The Queen’s Code

Famous for her library, command of languages, arts patronage, and gender defiance, Queen Christina ruled Sweden from 1632 until her abdication in 1654. In this letter to Pope Alexander VII, sent the year after she ceded the throne, Christina deploys a substitution cipher to conceal its content. She references her recent secret conversion to Catholicism, which she would not publicly declare for several months. The copy (dupplicado) of her letter is accompanied by a Spanish transcription as well as a key to the cipher: vowels are represented by multiple numbers to strengthen the encryption.

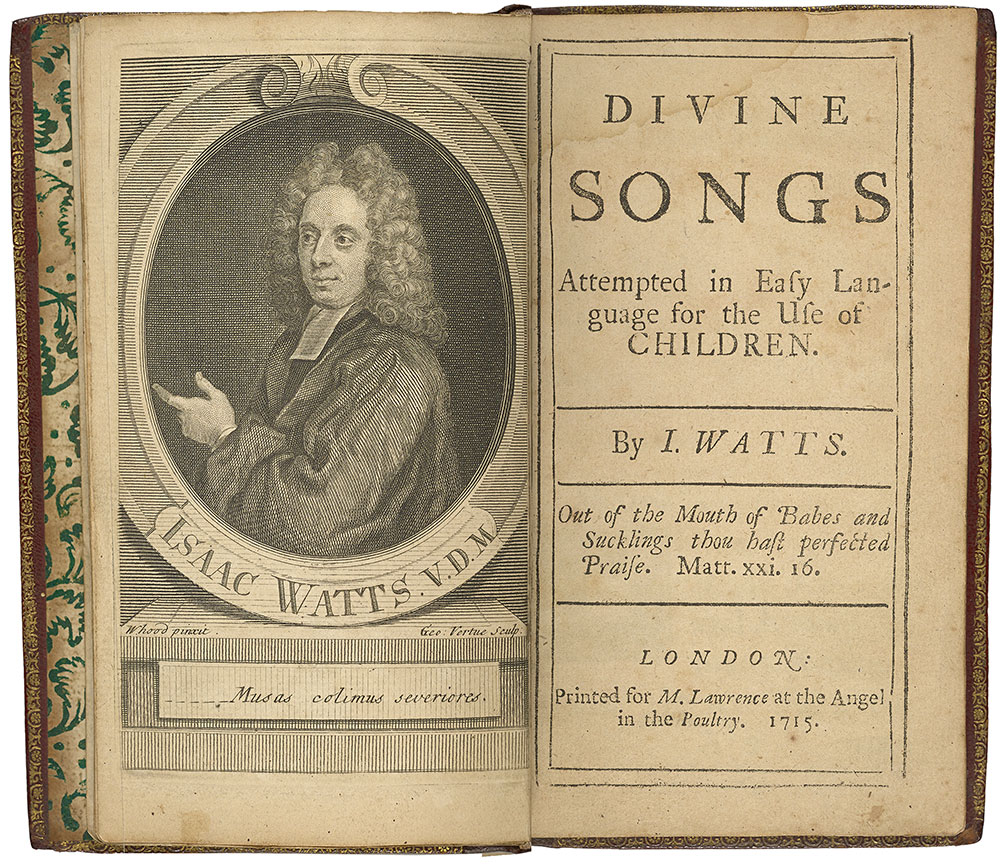

The Bane of Lewis Carroll

One of the distinguishing qualities of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) was that it lacked a moral. Rather than aiming to teach or, ideally, teach and delight, Lewis Carroll’s book was solely intended to delight and inspire. Carroll was rebelling against the continuing popularity of works such as Watt’s Divine Songs, a collection of poetry and hymns meant to cultivate reverence and morality in the minds of youths. In Alice’s Adventures, Carroll mocks one of Divine Songs’ most famous poems by changing Watts’s verse about a hardworking bee into one about a crafty crocodile. Works both by Watts and Carroll were among the few examples of children’s literature collected by J. Pierpont Morgan.

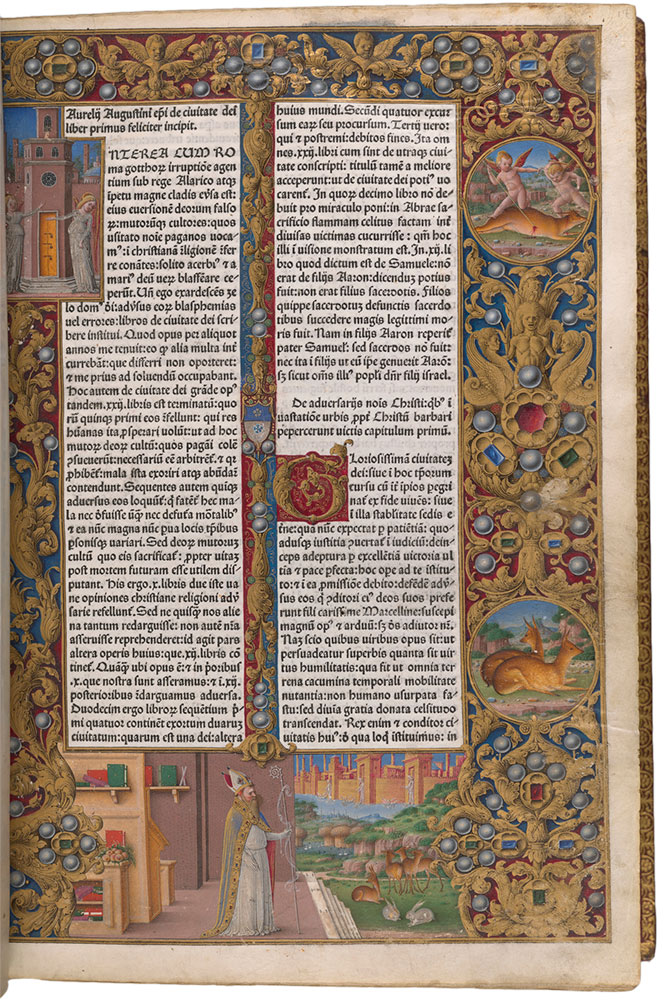

A Gem of a Book

Augustine’s City of God, one of the most significant works of Christian philosophy, was incredibly popular throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. This printed edition was dedicated to Pietro Mocenigo (1406–1476), chief magistrate of Venice, for whom the lavishly illuminated frontispiece was added by Girolamo da Cremona. The bottom scene represents Augustine in his study. To his right is a minuscule landscape showing the City of Man with the City of God’s imposing walls looming in the heavens above. Girolamo’s decorative motifs include typical putti and deer but also representations of pearls and precious gems, glorifying both Mocenigo and Augustine’s text.

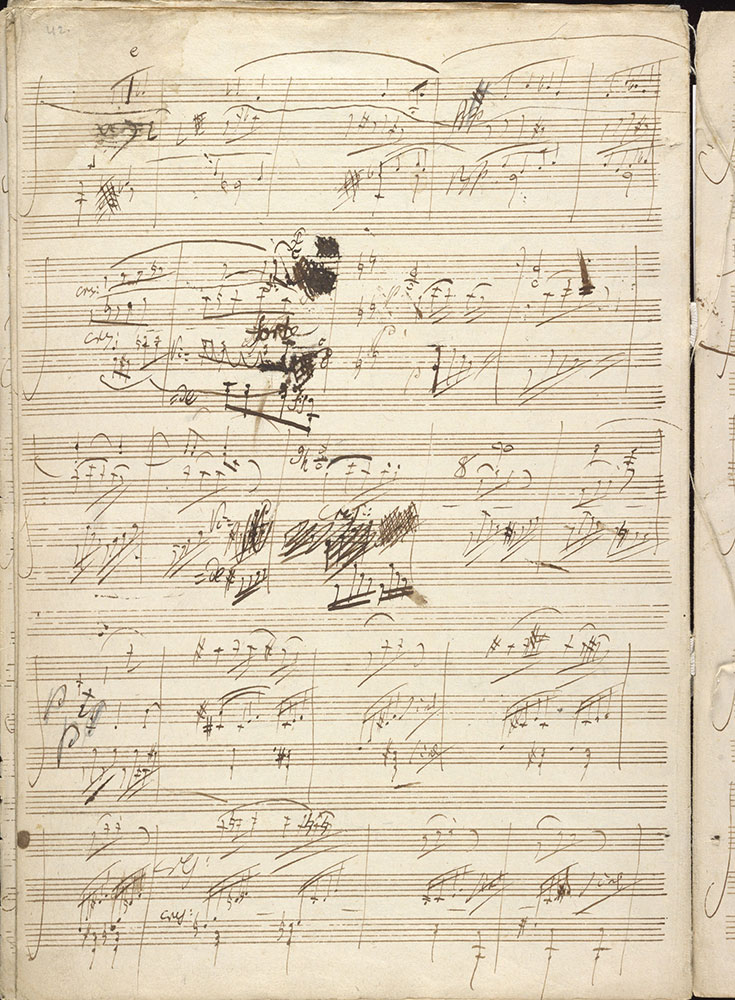

Morgan Spots a Musical Gem

When the noted Florentine bookdealer Leo Olschki acquired this long-lost manuscript of Beethoven’s last sonata for violin and piano, the press reported that musicians performed it in his home from this manuscript. (They must have been familiar with the music beforehand, as Beethoven’s notations are not easy to read at sight.) After meeting J. Pierpont Morgan, Olschki had quickly become the collector’s colleague and a trusted source of information. When Morgan was alerted to Olschki’s acquisition, he visited Florence and seized the opportunity to purchase this score.

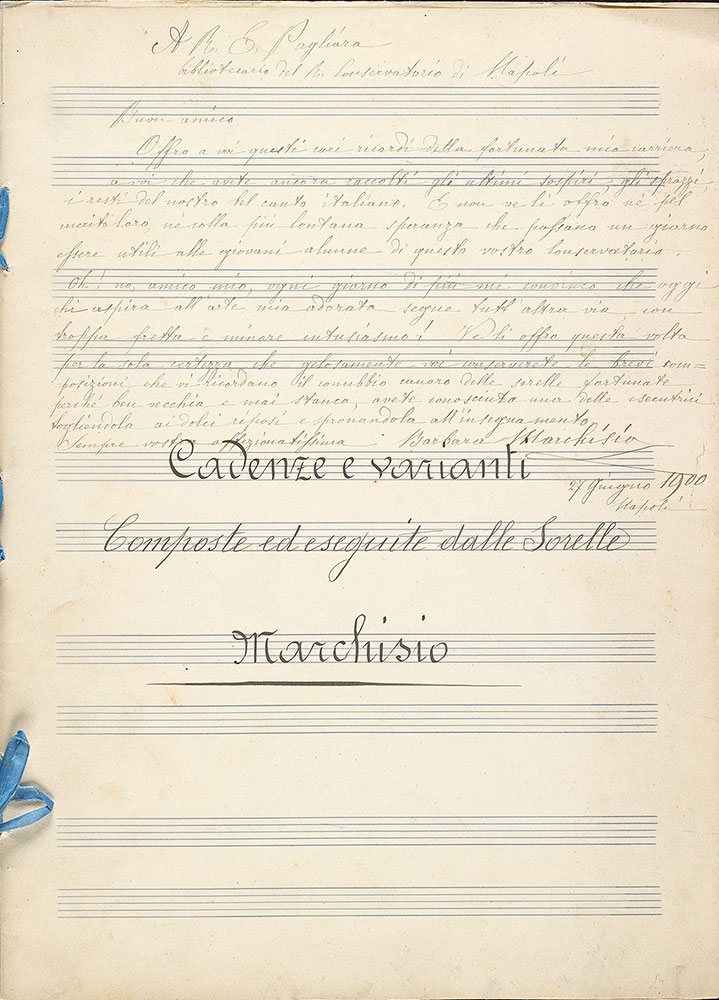

A Bel Canto Star Looks Back

At age sixty-seven Barbara Marchisio, teaching at a Naples conservatory, inscribed this manuscript to the school’s director as a souvenir of the “last sighs” of bel canto opera. In their prime, Barbara and her sister, Carlotta, had ranked among Europe’s finest bel canto singers, friends and favored voices of Rossini’s and other Italian opera composers. Cadenzas— unaccompanied passages like those the sisters created for their performances of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville—were improvised or composed in advance by the performer and inserted at fermatas (pauses) in the score. By 1900 this performer’s prerogative to expand a composer’s work had faded, yielding to rigid fealty to the printed music, an ethos that became common in the twentieth century.

“The Unfinished Hours”

This Book of Hours was illuminated by two outstanding painters, Enguerrand Quarton and Barthélemy d’Eyck. Here, the Evangelist Matthew, equipped with eyeglasses, reads from a copy of his Gospel. Though much of the manuscript’s decoration was left incomplete, the artists’ intentions are indicated by sketches, notes, and blank spaces reserved for motifs. J. Pierpont Morgan’s interests paralleled those of British aristocratic collectors of an earlier generation, and he purchased items from their libraries when they came onto the market. He obtained this manuscript from the library of Bertram, fourth Earl of Ashburnham (1797–1878), from whose collection Morgan also acquired the late ninth-century Lindau Gospels preserved in a jeweled binding.

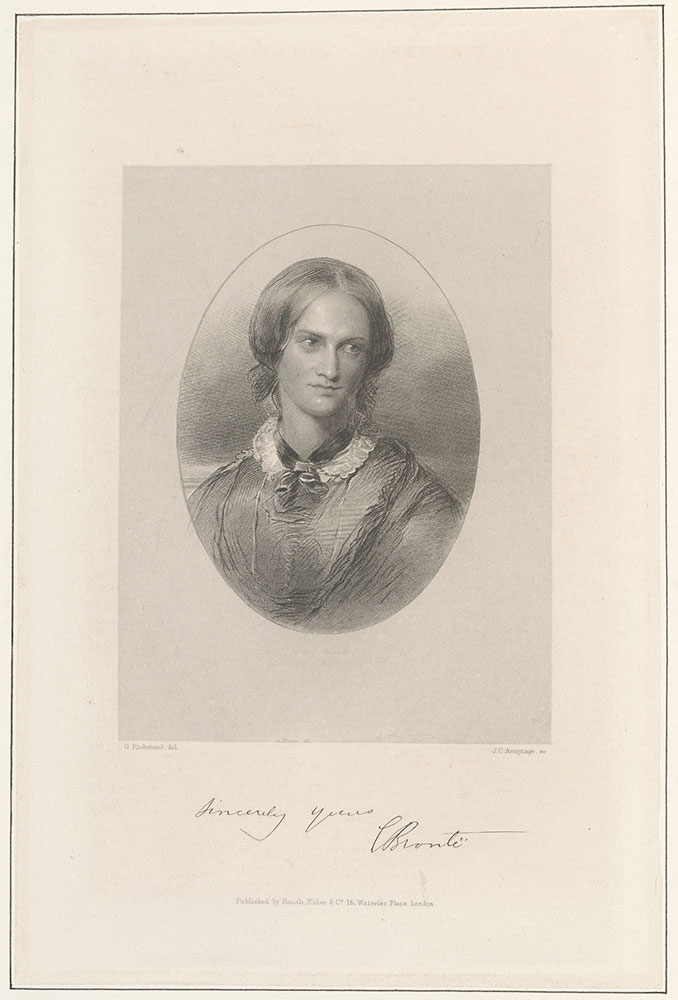

Charlotte Brontë’s Minuscule Arthuriana

More than a decade before Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë cowrote a series of short tales with her siblings Branwell, Emily, and Anne. They inscribed these stories within handmade books to share with one another. Their fictional worlds of Glass Town, Angria, and Gondal are populated with characters the children invented when Branwell received a box of toy soldiers as a gift. Each soldier became a character; Charlotte’s favorite was Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Zamorna and son of the Duke of Wellington. On view in the East Room is Brontë’s manuscript of Arthuriana, or, Odds and Ends , which contains short tales and poems about Arthur’s life. As with the other manuscripts the Brontë siblings made as adolescents, it combines various prose and verse genres and is written in a miniature script.

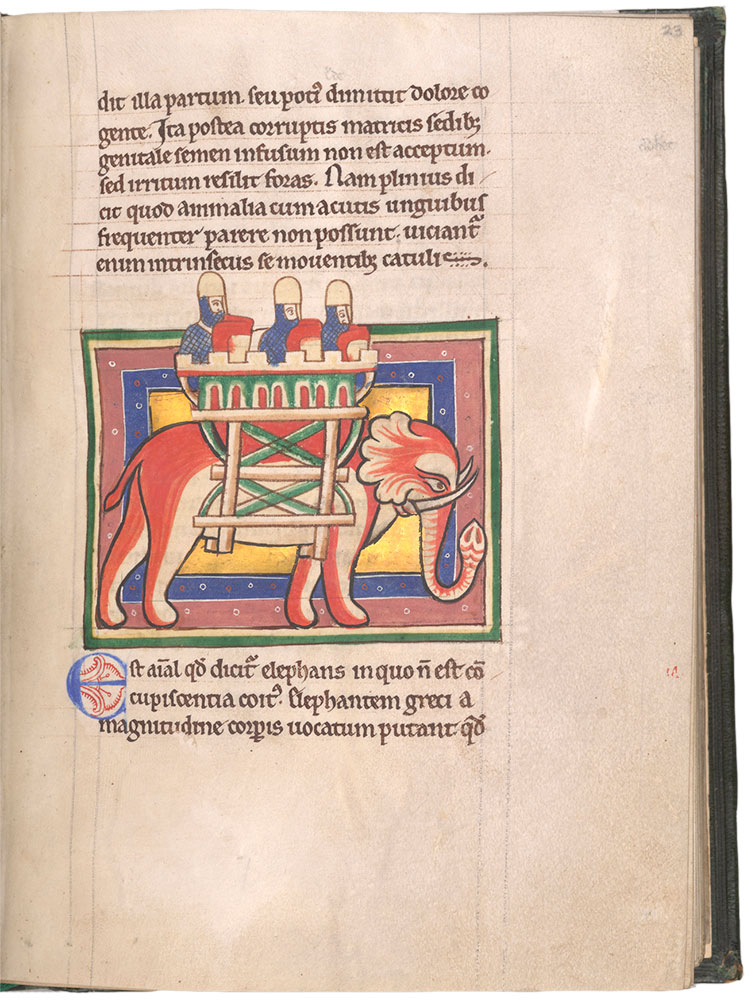

A Manuscript Menagerie

This miniature in the Worksop Bestiary, a book of beasts both real and imagined, shows how Persians and Indians placed howdahs (wooden towers) on elephants to carry warriors into battle. The bestiary, one of the finest extant, was acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1902 from the English industrialist Richard Bennett (1849–1930). Of the 107 manuscripts Morgan obtained from Bennett, 30 had previously been owned by the famous designer and revolutionary thinker William Morris. As this purchase demonstrates, Morgan efficiently augmented his holdings by buying entire libraries formed by discriminating European collectors. Junius Spencer Morgan (1867–1932) brokered the sale and later catalogued the Bennett manuscripts for his uncle.

Other items on display in the East Room, not pictured here, include Morgan’s 1897 acquisition of the manuscript of Discorsi del poema eroico (Discourses on the Heroic Poem), written around 1594 by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso (1544–1595); MA 462.26. The first manuscript J. Pierpont Morgan acquired that featured full-page miniatures is also on view–a splendid Indian Ragamala (Garland of Ragas), inscribed in Braj Bhasha, a western dialect of Hindi, probably in Jaipur, India, around 1800; MS M.211, fols. 13v–14r. In 1905, Morgan bought a manuscript by the inventor Samuel Morse (1791–1872) from the journalist John Mullaly, who was Morse’s secretary during the early stages of the laying of the transatlantic cable. Currently on display is Morse’s elegant diagram, titled The Original Telegraph made in the N. York city University in the autumn of 1835; MA 901.5. The museum’s formidable collection of music manuscripts was chiefly built over the century following Morgan’s death and continues to grow. A recent example featured in this rotation is the 1948 autograph manuscript of Le soleil des eaux by twentieth-century French composer Pierre Boulez (1925–2016).

Inside the Bookman’s Paradise

The desire to preserve and display manuscripts, rare books, and artworks inspired the creation of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, which the New York Times called “the paradise of the bookman” in 1908. Architect Charles Follen McKim presented his initial designs for the space in 1902, and construction was largely completed by 1906, although decoration of the rooms continued until Morgan’s death in 1913.

Making an Entrance

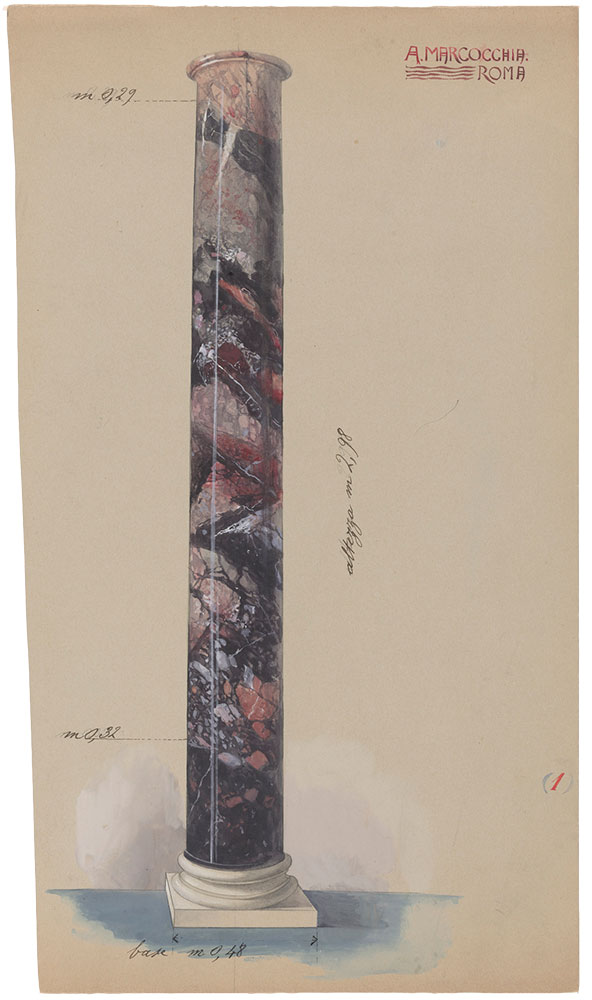

Charles Follen McKim’s initial elevations for the Library’s Rotunda included sculptural reliefs over the doors in a tripartite (three-part) design. A construction photo likely dating to late 1905 reveals that this scheme was at least partly realized before the decision was made to replace them with painted lunettes, designed by H. Siddons Mowbray. Mowbray’s panels were among the last elements of the decorative scheme to fall into place: they were installed in 1906, when interior work was nearly complete. One further modification, indicated in pencil in the elevations, was the raising of the stylobate, or the pilasters’ base—perhaps to align the pilasters with the green cipollino-marble columns sourced to flank the entrances to the East and West Rooms.

By fall 1905, three years into the process of designing and building Morgan’s Library, the architect Charles Follen McKim secured four freestanding marble columns from Roman art dealers. Two columns, in black-veined Africano marble, came from Alessandro Marcocchia; another pair, in rose-toned breccia, was supplied by George Williams. The renowned American lighting designer E. F. Caldwell fitted these four columns with alabaster bowls carved with delicate classical-themed reliefs. The columns replaced Caldwell’s bronze standards topped with globe lights, which had struck a discordantly modern note in the Morgan’s Renaissance-inspired interior.

Look Up!

McKim’s earliest designs for the Rotunda’s dome were based on Raphael’s ceiling frescoes in Pope Julius II’s personal library at the Vatican’s Stanza della Segnatura. McKim modified Raphael’s layout slightly, and the artist H. Siddons Mowbray ultimately made twelve paintings for the dome: four roundels, four rectangular panels, and four small quadrangular ones. Mowbray’s roundels portray female personifications of the Renaissance ideals of humanist learning— Art, Science, Philosophy, and Religion—surrounded by putti. The figures and their flowing pastel garments convey both the appeal of Raphael’s graceful forms and an appreciation for the High Renaissance palette. Mowbray adapted Raphael’s models, however, as is most evident in the image of Religion. Though based on Raphael’s depiction of Philosophy, Mowbray’s Religion has shifted her pose and holds a cross, obfuscating part of her throne.

McKim’s initial proposal for the apse reveals that his plan was based on the garden loggia of the Villa Madama, Rome, which Raphael designed around 1518. The artist H. Siddons Mowbray diligently followed McKim’s general scheme, although he simplified the palette to blue and white with touches of gold. This study for the center octagonal relief in the lower register depicts the Roman goddess Diana hunting. The figures are slightly distorted to compensate for the angled view from below and the lighting from the oculus.

Collections Spotlight is funded in perpetuity in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker.