Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators.

Below are some highlights of the current rotation, including a special installation in the Rotunda entitled Fighting to Learn: Black Enfranchisement and Education in the Gilder Lehrman Collection. Drawn from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, these artifacts explore the Black community’s persistent struggles for emancipation, enfranchisement, and the right to quality education, highlighting how these efforts have intersected during the past two centuries. Among the items are an early example of Black women’s history from the perspective of a Black woman--The Work of the Afro-American Woman by Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855–1948)—as well as others related to key moments and figures—from the Civil War to Josephine Bruce (1853–1923) to the Little Rock Nine—all of which point to a multigenerational political project of resistance and respectability.

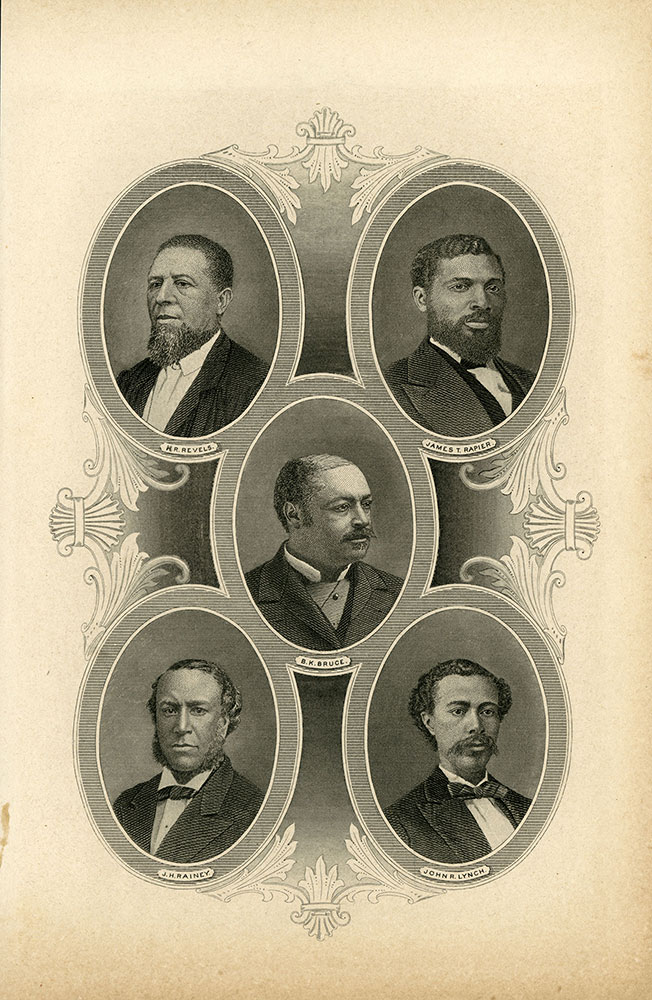

Rising with Reconstruction

The “power couple” Blanche Kelso Bruce and his wife, Josephine Bell Willson Bruce, symbolized the ambitious goals of Reconstruction: political enfranchisement, property ownership, and career and educational advancement. Blanche (1841–1898) is depicted among his contemporaries in this portrait of Black congresspeople from the Reconstruction era. He was born enslaved and, after emancipating himself during the Civil War, made an unsuccessful attempt to join the Union Army. Unable to serve in the military, however, he focused his attention on education, first in teaching, and later, in 1864, organizing Missouri’s first school for Black children. As a politician, Bruce was only the second Black American to serve in the US Senate and the first elected to a full term.

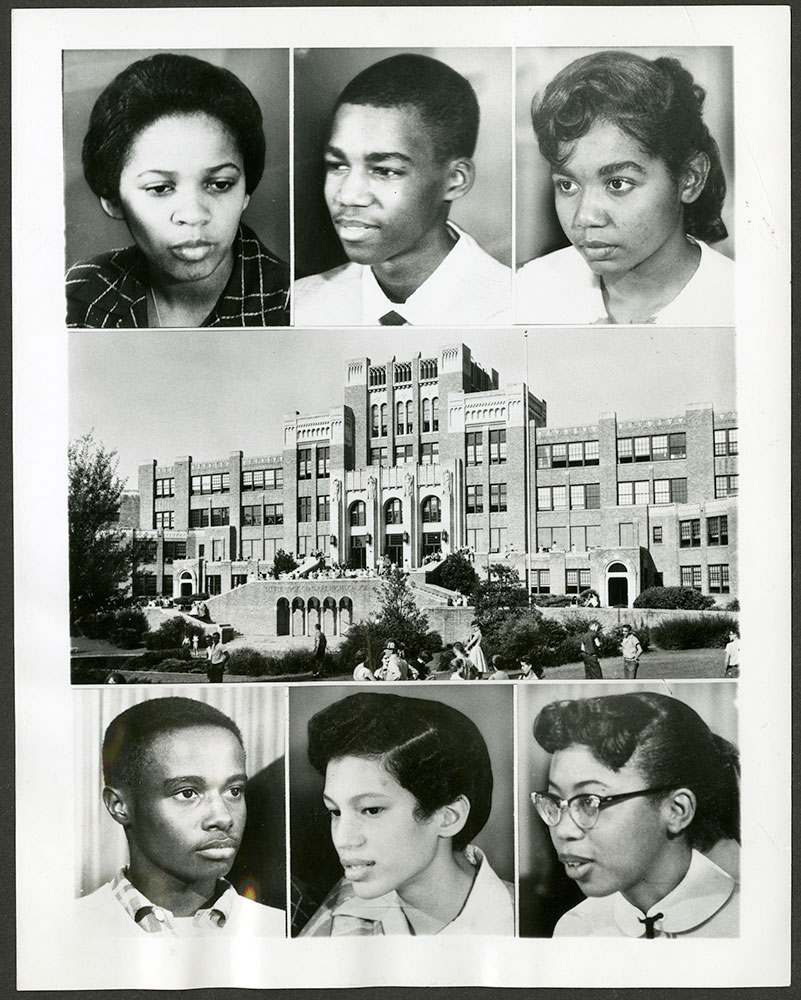

Education Is a Right

Black Americans have been organizing for equal rights in education for generations. In 1957 the struggle to desegregate schools in the South reached a tipping point at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. In response to violence against protesters and a gubernatorial effort to block integration, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the US Army’s 101st Airborne Division to escort nine Black teenagers as they courageously entered the school. It was the first presidential deployment of troops in the South since Reconstruction. Seen in this Associated Press photograph, from left to right, are six of the Little Rock Nine (top to bottom, left to right): Gloria Ray, Terrance Roberts, Melba Pattillo, Jefferson Thomas, Carlotta Walls, and Thelma Mothershed.

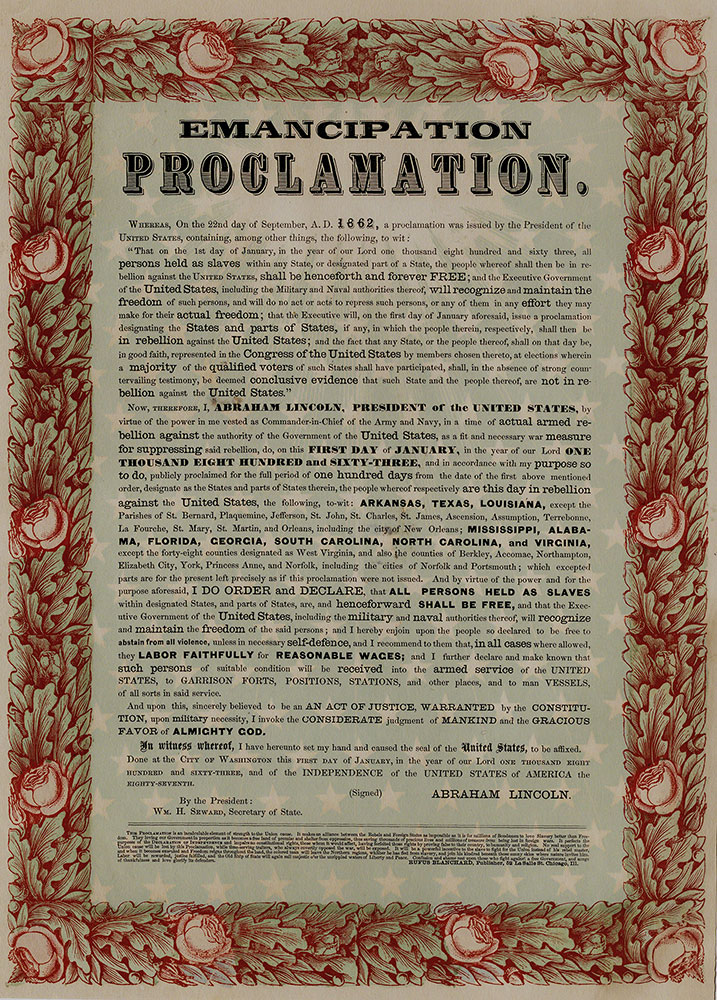

Proclaiming Freedom

On 1 January 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order effectively declaring freedom for all enslaved peoples held in “rebellious states.” Even though the proclamation did not officially end the institution of slavery in the United States, it was marked by “Grand Celebration” events across the nation, from Massachusetts to Missouri. This broadside edition of the proclamation was published by the bookseller Rufus Blanchard (1821–1904). Over several decades, Blanchard authored and published several books and maps, including his 1882 collection of poetry, Abraham Lincoln: The Type of American Genius.

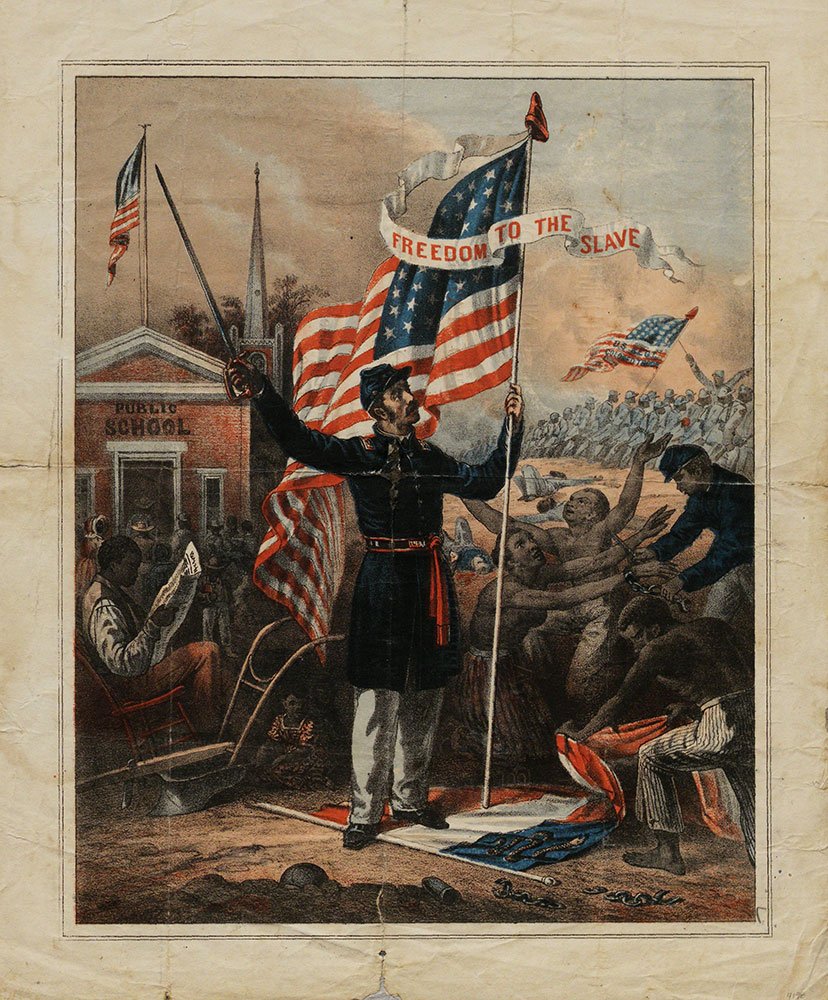

A Sacrifice for Future Generations

The Emancipation Proclamation included a provision that enabled Black men to enlist in the Union Army and Navy. Recruiting Black servicemen in the war effort would prove critical to realizing the proclamation’s stated promise of mass liberation—nearly 200,000 Black men had served by the end of the Civil War. This illustrated broadside, shown above, celebrates Black volunteer military service in an attempt to recruit more Black soldiers. It also shows newly emancipated citizens entering a public school, illustrating the idea that victory over slavery would lead to new educational opportunities for future generations of Black Americans.

Tokens of the True Image

According to pious legend, as Jesus was carrying his cross to his place of execution, a woman stepped forward to wipe the sweat and blood from his brow. Her handkerchief was imprinted with Christ’s face and became a holy relic: the Vera Icon (True Image). Fittingly, the woman was christened Veronica. These badges attest to the popularity of the relic, which existed in several versions and was venerated by pilgrims in Rome and elsewhere. Such tokens could be fastened to hats, cloaks, bags, and walls, as well as sewn into prayer books. Painted copies were also included in the borders of manuscripts. Aristocrats, including the dukes of Burgundy and their families, were among the most devoted to the Vera Icon.

Master of the Burgundian Prelates

This Book of Hours is the finest surviving manuscript painted by an anonymous artist active in Burgundy around 1470–90. One of the most original illuminators of the era, his work was esteemed by local clerical patrons, which is why he has been christened “the Master of the Burgundian Prelates.” His inventiveness is evident in the remarkable miniatures in this book. All are full page (a rare feature) and blur traditional distinctions between miniatures and borders. His subject matter also departs from the norm. Central compositions, including this Crucifixion, are embellished with subsidiary scenes. Many of these represent parallel events from the Old Testament drawn from the Biblia pauperum, a copy of which is also on display.

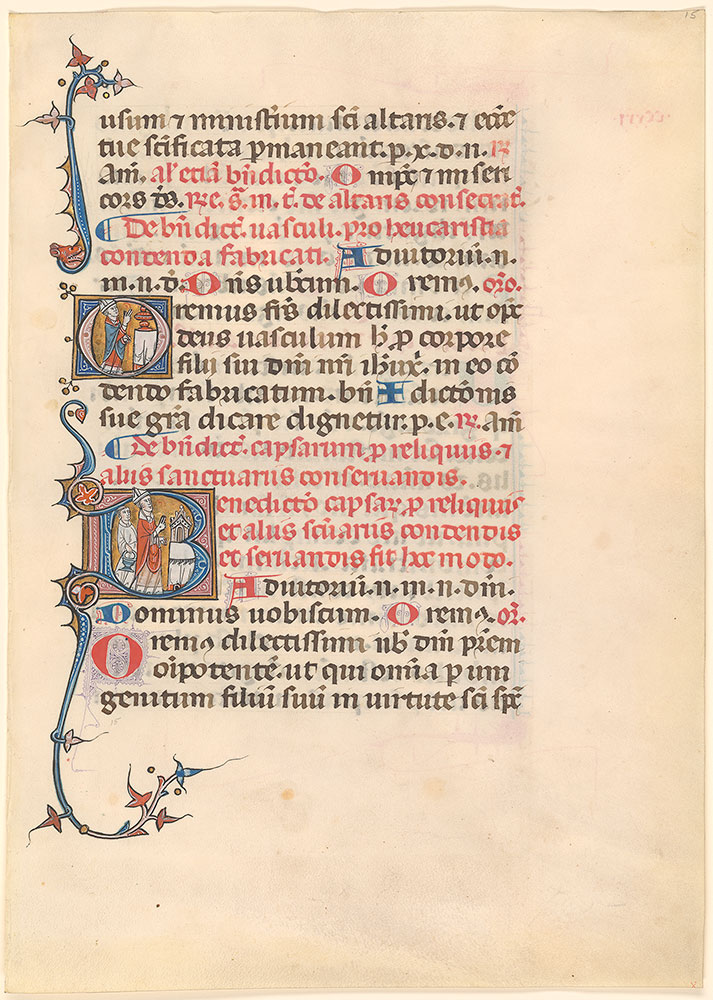

Initial Blessings

This leaf is from a Pontifical, a book containing liturgical services performed by popes or bishops. Its illuminated initials not only enhance its appeal but also illustrate the ceremonies described in the surrounding text. Within an O, a bishop blesses a vessel resting on an altar. Below, in a B, another bishop blesses a reliquary. The leaf was originally part of a grand liturgical book made in Avignon, the seat of the Roman papacy from 1309‒76. Over time, at least ninety-eight pages from this manuscript were removed and dispersed. The volume still survives, however, in Seville’s Biblioteca Colombina, founded by Fernando Colón, son of Christopher Columbus.

Ars moriendi (The art of dying), Netherlands, ca. 1466–67. Purchased on the Gordon N. Ray, Curt F. Bühler, L. Colgate Harper D-1, and Henry S. Morgan Reference Funds, and as the gift of T. Kimball Brooker, Martha J. Fleischman, Mr. G. Scott Clemons and Ms. Karyn Joachino, Marguerite Steed Hoffman and Tom Lentz, and Lucy and Lawrence Ricciardi, 2022; PML 198786

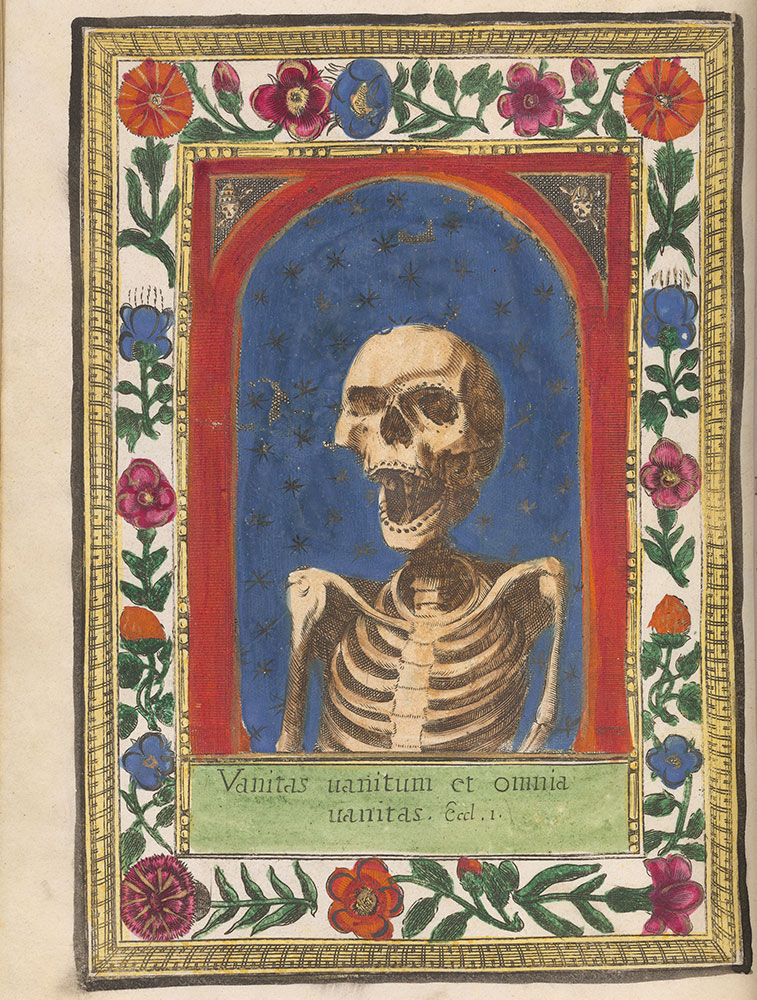

A Memento Mori for Nuns

With its mouth gaping in a silent scream, this skeleton would have served as a potent memento mori, or reminder of death, for the manuscript’s original readers: the nuns of the Convent of St. Agatha in Padua. Below the grim figure, a biblical verse declares the vanity of worldly things. A calendar on the facing page records the death dates of the women who lived at the convent in the seventeenth century. Prayers would have been said and services held on the anniversary of their deaths. The manuscript contains the Rule of St. Benedict, providing instructions for monastic living, followed by various religious works. Notably, the volume mixes handwritten text and printed images carefully colored by hand.

Demons Doing What Demons Do

The Ars moriendi was a popular late medieval narrative in which demons tempt a person on their deathbed to commit mortal sins. Each temptation is immediately followed by the appearance of saints and angels, who rally the dying to embrace the opposing virtue. In this panel, demonic figures point to sins the moribund person may have committed—acts of fornication, perjury, and murder—in order to cause them to despair of God’s mercy. Both the images and facing text were reproduced from engraved wooden blocks. Such blockbooks, as they are now called, were printed “on demand” at a customer’s request. Other than the Morgan’s copy, only one other copy of this book is known to survive.

Jeweled Binding Made for Judith, Countess of Flanders

Judith’s father, Count Baldwin IV of Flanders, named her after Charles the Bald’s daughter, who married the first Count Baldwin. In 1051 she and her husband Tostig (the son of Godwin, brother of King Harold) went to England. Exiled in 1065 and widowed at age thirty-eight in 1066, in 1071 she married Welf IV of Bavaria, whose ancestral monastery was Weingarten. She died in 1094, leaving her books to Weingarten, where she was buried. The binding, possibly Germanic work combining delicate filigree and cast figures representing Christ in Majesty and the Crucifixion, was added in the last third of the eleventh century. The title on the cross, “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” is of translucent green enamel.

An Art Nouveau Binding for a Poet and Muse

A dazzling conversationalist, artist’s muse, and author who sensuously captured a love of nature, Anna de Noailles is among the Belle Époque’s most celebrated poets. Dubbed by some scholars as the “midwife” of Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time, she was the Paris-born daughter of a Romanian prince. Proust lauded her work for achieving the effects of Impressionist art in literature.

In many of Noailles’s poems a butterfly symbolizes fleeting life. This art nouveau binding on her collection Les éblouissements features sculpted and incised leather butterfly wings, accented with opalescent and semiprecious stones—a nod, no doubt, to the title, which evokes dazzling lights.

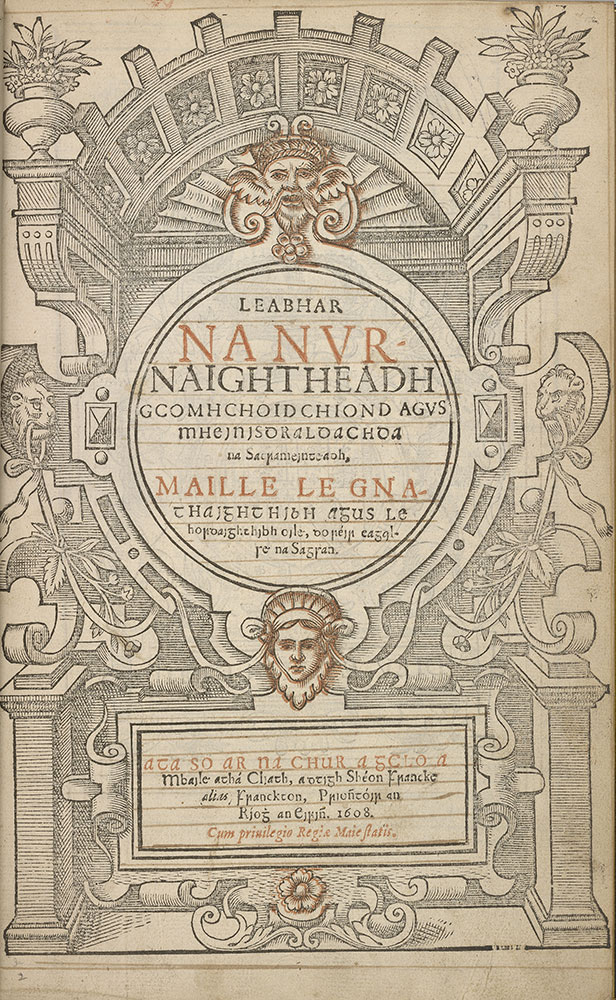

One of the First Uses of Gaelic Type

This copy of the first Irish translation of the Book of Common Prayer belonged to Sir Arthur Chichester, the British-born lord deputy of Ireland from 1605 to 1616. Chichester had sponsored the translation shortly after England’s royal army (partly under his command) brought most of Ireland under British rule. Despite centuries of occupation, Ireland had maintained a flourishing culture and language. The Gaelic type used here was not created until 1570, however, when it was commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I to disseminate Protestant literature. For this Book of Common Prayer, the royal printer based in Dublin added one character to Elizabeth’s font: the letter c with an overdot (ċ), indicating a more sonorous consonant, now transliterated as ch.

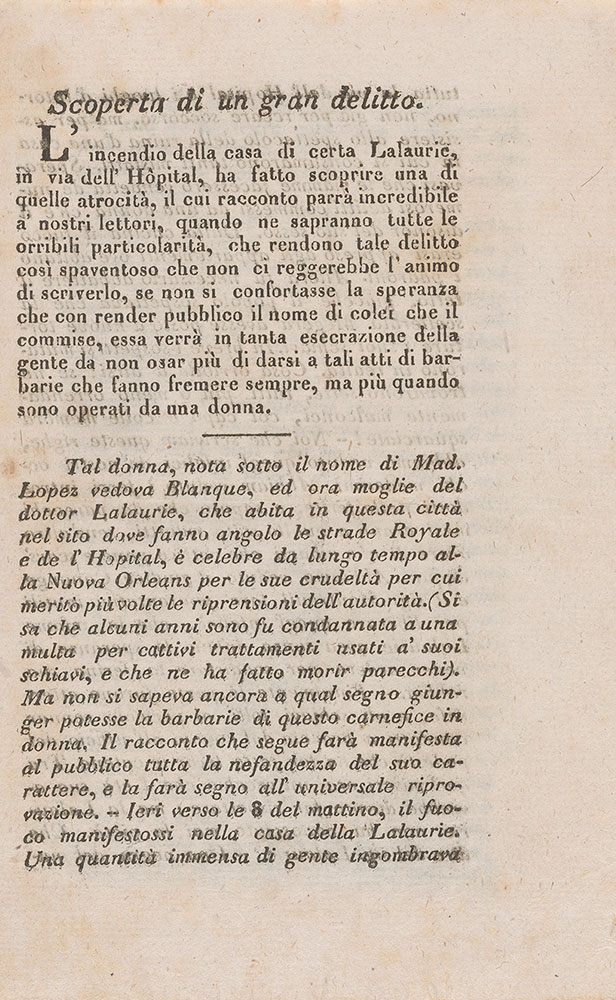

The Horrors of Enslavement

On 10 April 1834, people responding to a fire in the New Orleans mansion of Leonard and Delphine LaLaurie discovered that the couple was brutally torturing enslaved inhabitants of their household. Inside, a Black woman was bound by an iron collar, with heavy chains on her feet; another had a severe head wound. The scene was allegedly so horrific that the public turned on the LaLauries, ransacking and destroying their mansion the following day. The incident, which became known as the Affaire LaLaurie, was widely reported in Europe and America, garnering sympathy for the antislavery movement. This leaflet is the only known copy of contemporaneous reporting of the affair in Italy.

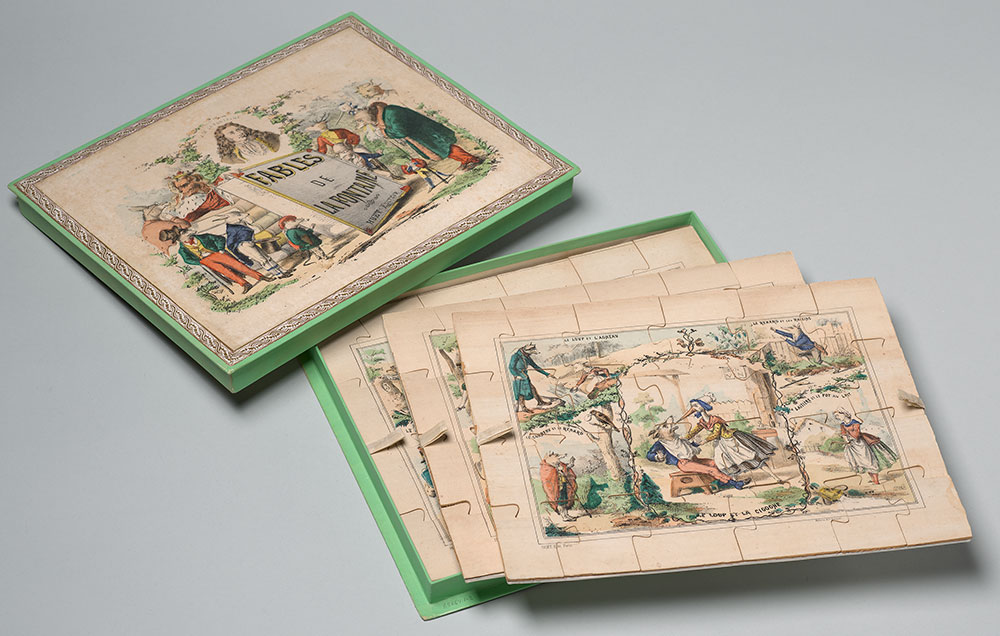

Fabulist Games for Children

La Fontaine wrote twelve volumes of fables in verse between 1668 and 1694. Many of these tales are liberal adaptations of works by Aesop, though La Fontaine also drew on a range of European and South Asian sources. His books were initially aimed at adults (indeed, some volumes were dedicated to King Louis XIV’s mistress). By the eighteenth century, however, La Fontaine’s fables were published as picture books and games, marketed for children’s amusement, memory exercises, and moral instruction. This game comprises three puzzles, each depicting multiple fables. Shown here are images illustrating “The Wolf and the Stork,” “The Fox and the Grapes,” “The Crow and the Fox,” and “The Milkmaid and Her Pail.”

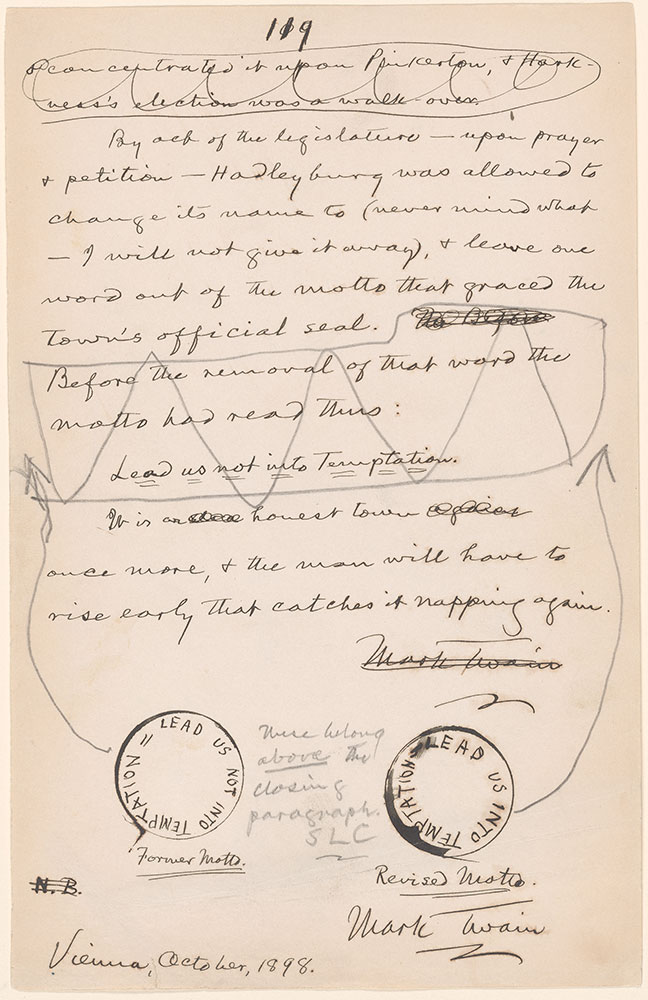

Virtue Untested

In Mark Twain’s classic tale of self-righteousness humbled, a stranger tests the virtue of the citizens of Hadleyburg, a town immoderately proud of its reputation for honesty. The stranger leaves in the town a sack of what appears to be gold coins, along with a note describing himself as the grateful recipient of good advice from a Hadleyburg resident many years ago. The bag can be claimed, he writes, by the individual who repeats, word for word, that advice. The coins that Twain has drawn on the last page of the manuscript contain, respectively, the phrase that will be the town’s undoing—“lead us not into temptation”—and a crucial tweak to Hadleyburg’s motto, which dispenses with the word “not.”

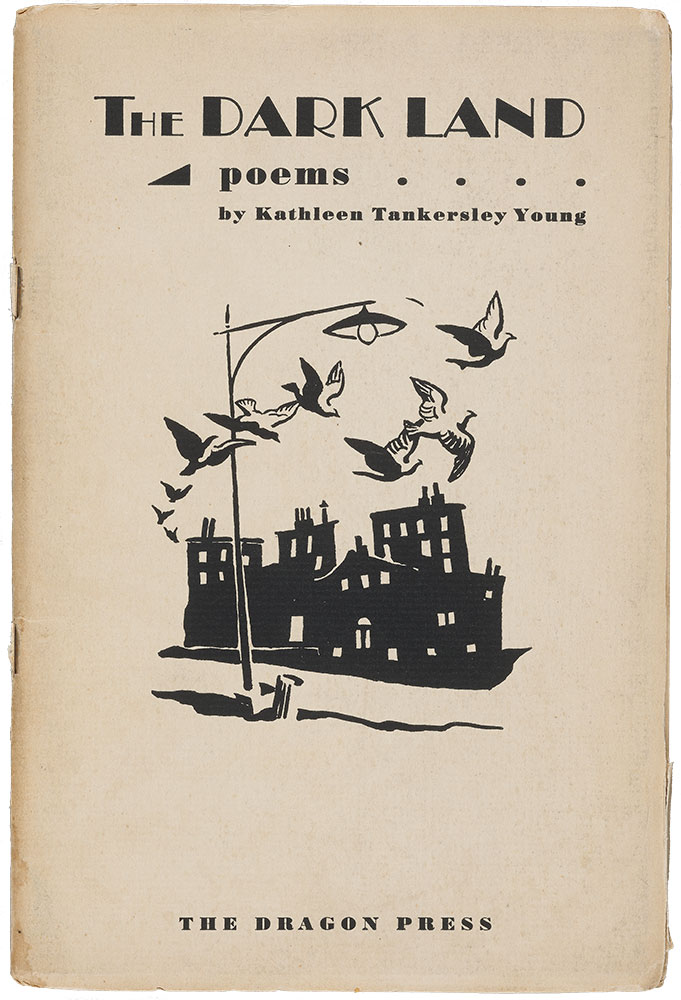

A Modernist Emerges from the Shadows

Kathleen Tankersley Young coedited the avant-garde magazine Blues in 1929 with Charles Henri Ford, published her own poetry and prose in journals and booklets, and created one of the first small-press imprints focused on American modernist poets. Her Modern Editions Press (1932–33) issued beautifully designed pamphlets by Kay Boyle, Bob Brown, and Paul Bowles, among others. Young, who lived most of her life in Texas and New York City, died in Mexico when she was barely thirty, apparently by suicide. Her writing is just now emerging from obscurity with Sublunary Editions' recent publication of her collected works.

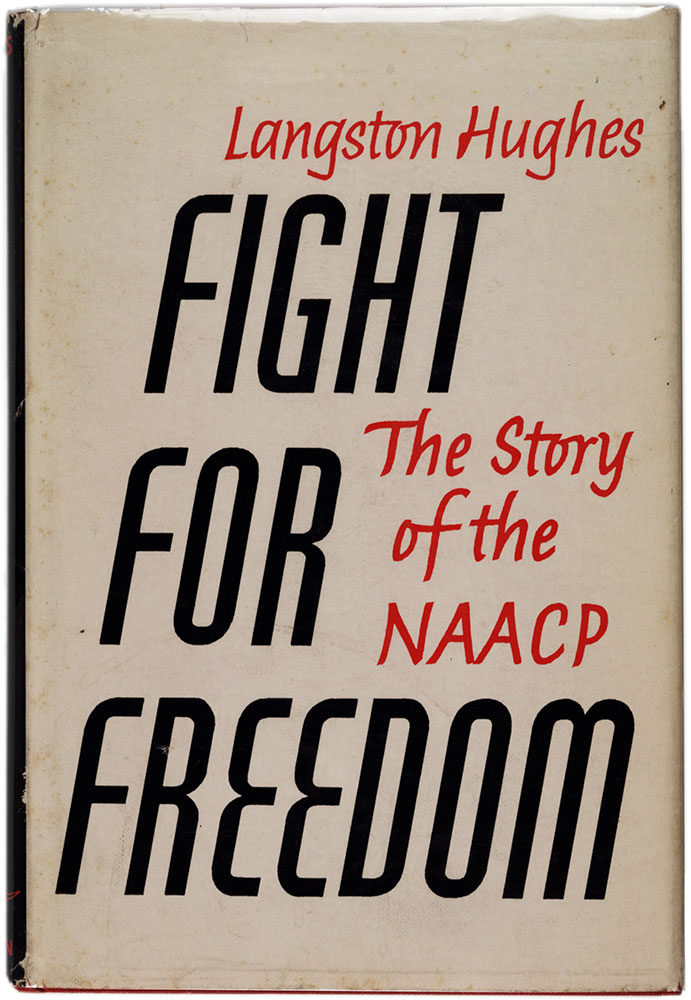

More Than a Poet

Langston Hughes not only wrote acclaimed poetry and prose but also forged working relationships with activists in order to promote racial justice. His book Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP was the first book devoted to the history of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. This copy was inscribed by Hughes to civil rights activist Raymond Johnson and signed by Dr. Evangeline Upshur Truman, a community organizer in Little Rock, Arkansas.

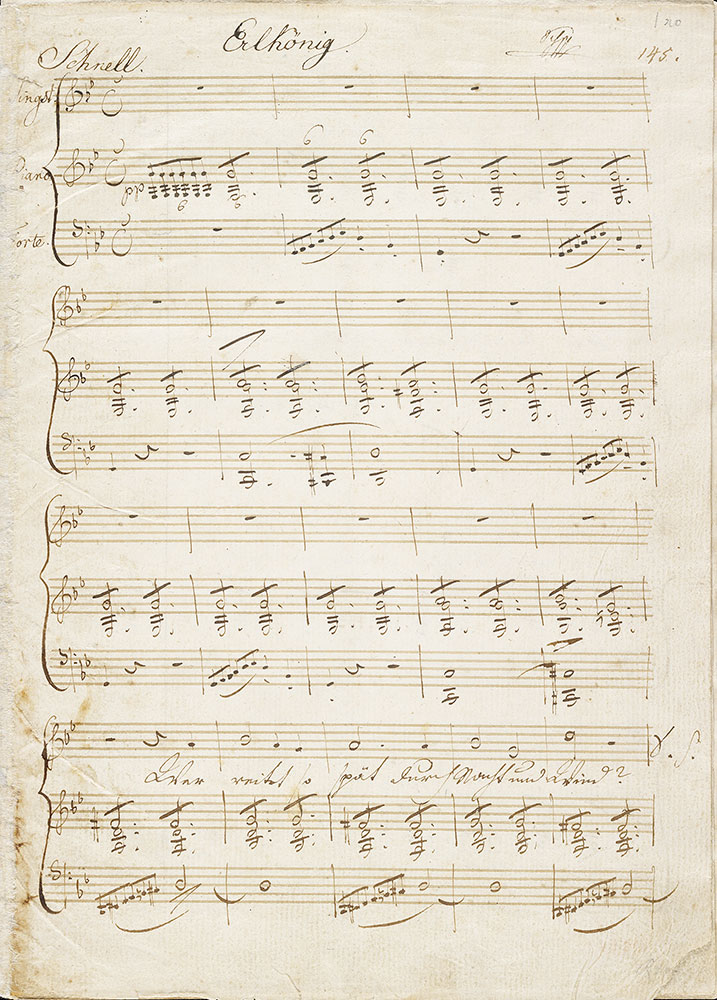

An Eighteen-Year-Old’s Gripping Inspiration

Although Goethe’s poem “Erlkönig” (1782) has been set to music by many composers, none has equaled the fame of Schubert’s haunting song. A breathless piano ostinato churns as a father rides headlong through a dark forest, clutching his frail son in his arms to escape the Erlking, a specter only the child can see and hear. Schubert’s original 1815 manuscript, written when he was eighteen, no longer survives; this is a later version in his hand, one of three existing sources. Schubert gave this manuscript to Benedikt Randhartinger, a school friend, who in 1838 presented it to the piano virtuoso and composer Clara Wieck, who would later marry the composer Robert Schumann.

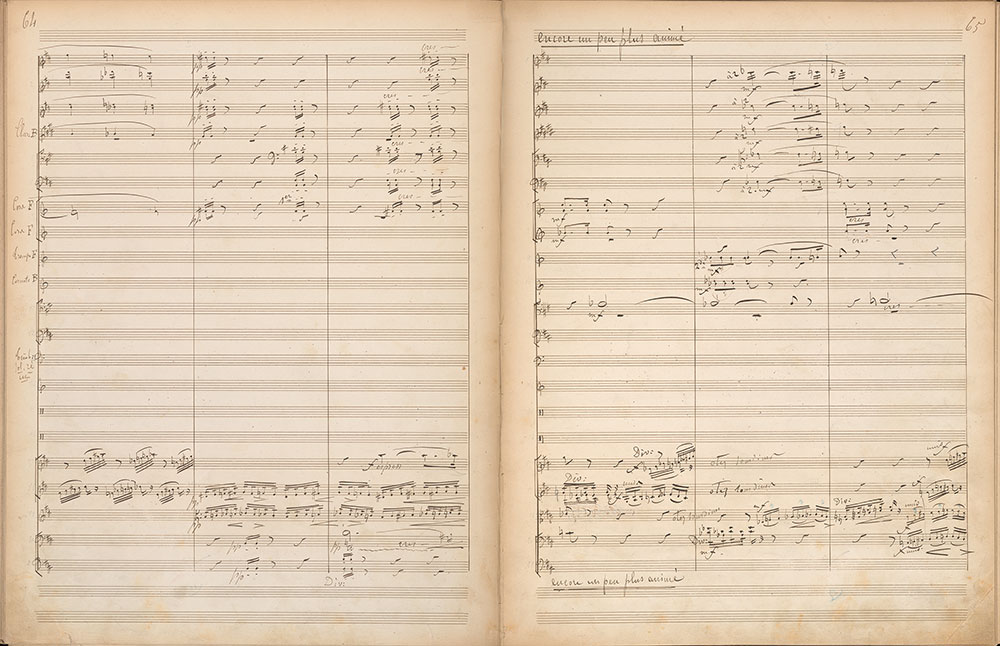

A Cursed Huntsman Tempts the Devil

Off to the hunt on a Sunday, a nobleman defies the warning of the church bells ringing in the Sabbath. Pursuing his prey by prideful and cruel means, he repeats the sins for which Satan was cast from heaven. Finally, a thunderous voice condemns him to wander forever, chased by devils.

César Franck recast this story, drawn from an eighteenth-century German poem by Gottfried August Bürger, as a symphonic poem, using instrumental music alone to relay the narrative. Like many of Franck’s best-loved works, Le chasseur maudit (The cursed huntsman) dates from the last decade of his life, when his music became more sensual and visceral—perhaps fueled by an unfulfilled love for his former student Augusta Holmès.

Benjamin Britten (1913–1976), Sketch for Billy Budd, act 2, [1950?]. Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection, 1982

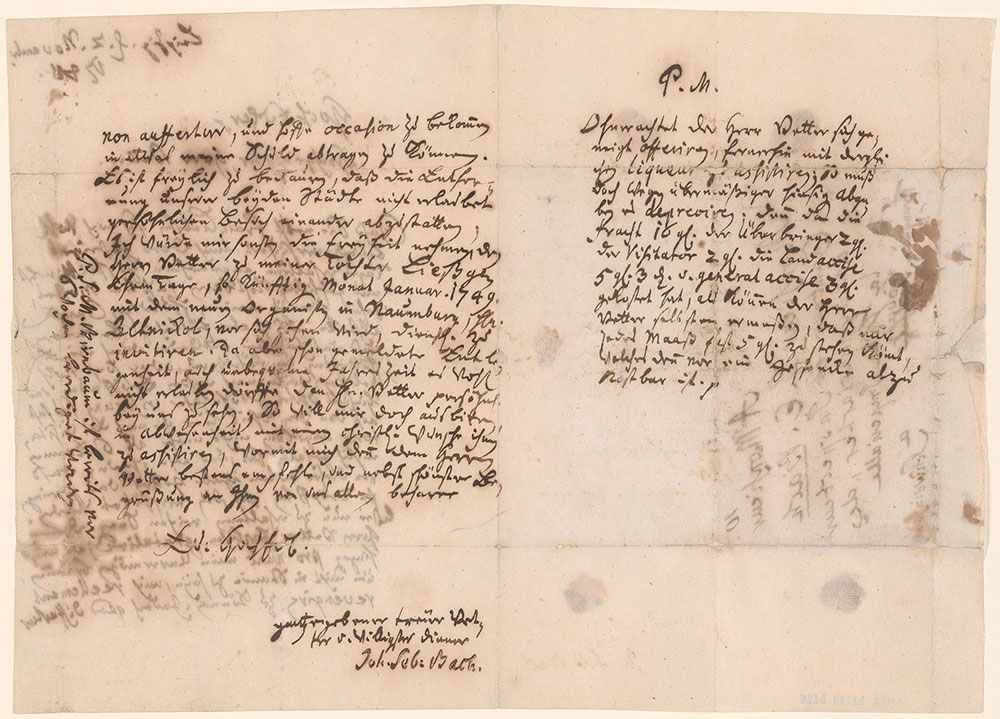

Bach, the Family Man

Written when Johann Sebastian Bach was sixty-three, as his eyesight began to fail, this is the last surviving letter in his own hand. It offers a rare view into his family life. Addressing his cousin Johann Elias Bach, the composer regrets that his daughter’s upcoming wedding, to be held at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig (where Johann Sebastian directs music), is too far away for his cousin to attend. After thanking Johann Elias for sending a cask of wine, which arrived two-thirds empty, Johann Sebastian adds a mildly humorous postscript: he declines the offer of more wine, listing the many costs—to the recipient (fees for delivery, customs inspection, and so on). “For a gift,” he writes, “[it’s] really too expensive.”

Working Out an Idea for Billy Budd

Britten’s opera Billy Budd is based on a libretto that E. M. Forster and Eric Crozier adapted from the novella by Herman Melville. Billy, a handsome young English sailor beloved by the ship’s crew, is accused of mutiny by an envious shipmate. Shocked by the accusation, Billy is overcome by his stutter and unable to respond. He is sentenced to death. The opera highlights unspoken homosexual desire suggested in Melville’s story. In this sketch, Britten lays out the melody for a chorus of sailors in act 2: “This is our moment, the moment we've been waiting for these long weeks.”

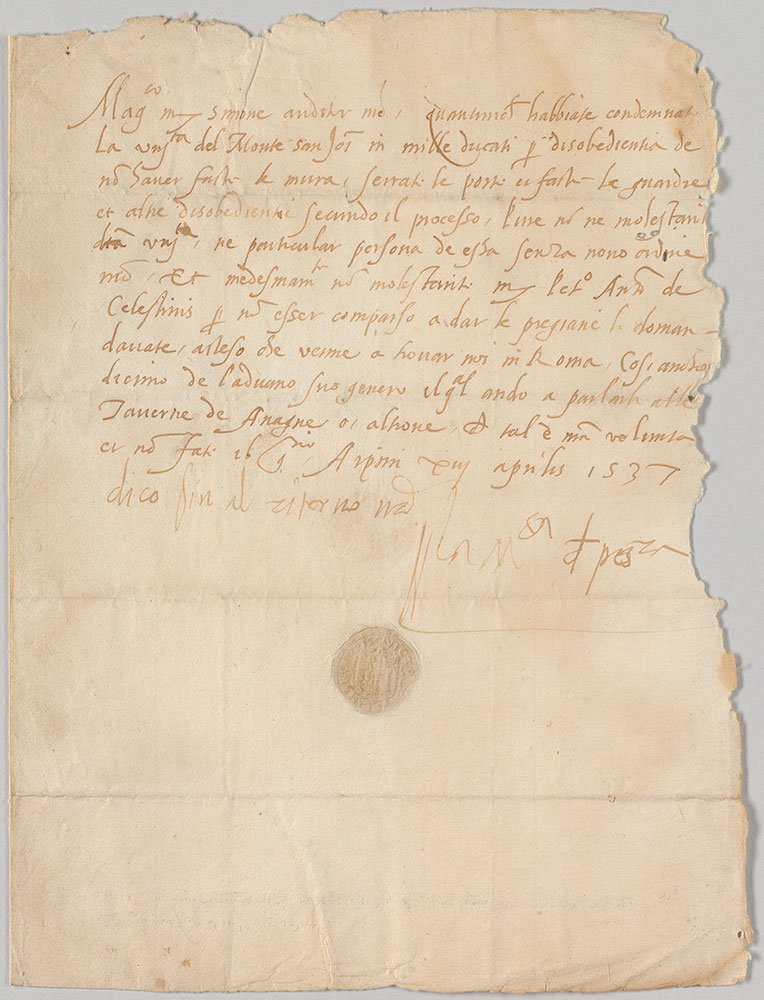

Renaissance Friends

When Vittoria Colonna signed this letter, in which she instructs a judge to take no action against a group of disobedient tenants on her estate at Monte San Giovanni, she was several years into an extraordinary friendship. In the mid-1530s Colonna, an Italian noblewoman and poet, met the artist Michelangelo in Rome, who was then in his sixties. The two soon began discussing matters of faith, exchanging manuscripts and drawings, and responding to each other’s work in letters and poetry. They remained close even after Colonna left the city, and Michelangelo was at her bedside when she died. “Death,” he wrote later, “deprived me of a very great friend.”

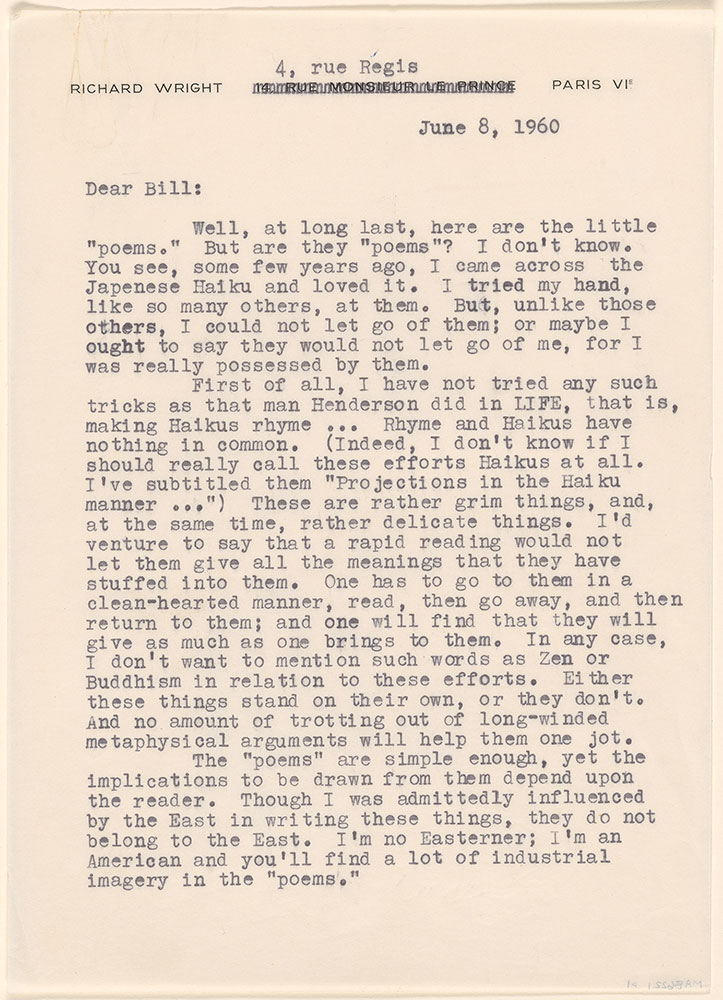

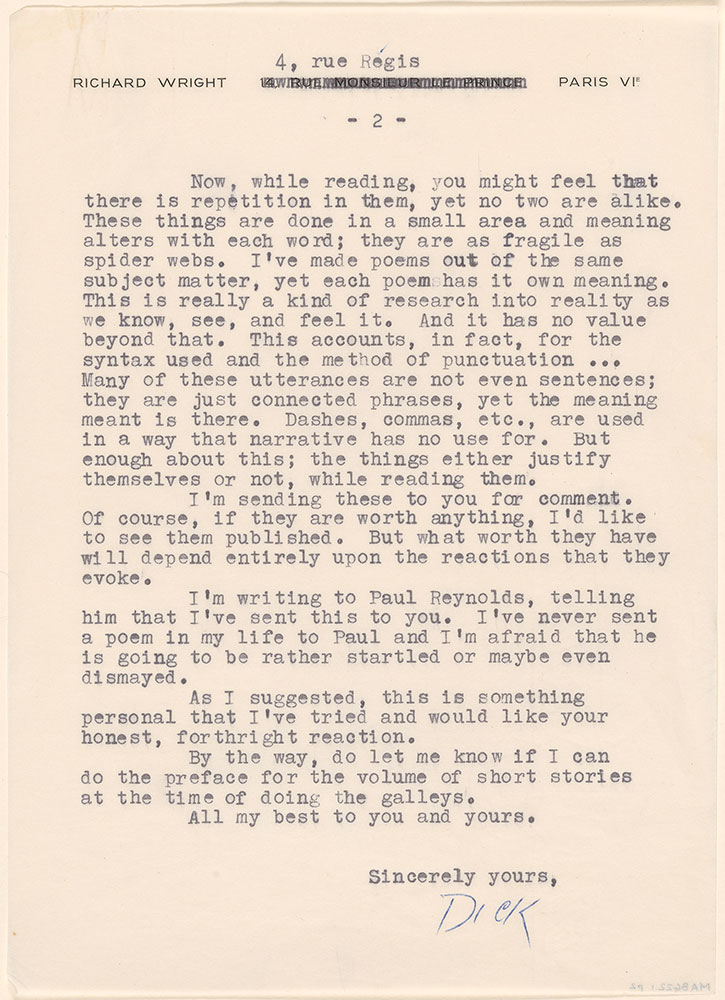

A New Direction

In the final years of his life, the American novelist Richard Wright experimented with the Japanese poetic form of haiku, writing over four thousand of them. In this letter to his friend and editor William Targ, Wright explains how they should be read: “One has to go to them in a clean-hearted manner, read, then go away, and then return to them; and one will find that they will give as much as one brings to them.” The poems were later collected in Wright’s Haiku, The Last Poems of an American Icon. Introd. By Julia Wright (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2012). The Poetry Society of America recently installed haiku by Wright on city walls in Downtown Brooklyn. One reads:

Leaving its nest,

The sparrow sinks a second,

Then opens its wings.

Reprinted by permission of John Hawkins & Associates, Inc. Copyright c 1998, 2012 by Ellen Wright.