Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, artistic techniques, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Shown here are examples of the Morgan’s objects currently featured in the East Room and Rotunda.

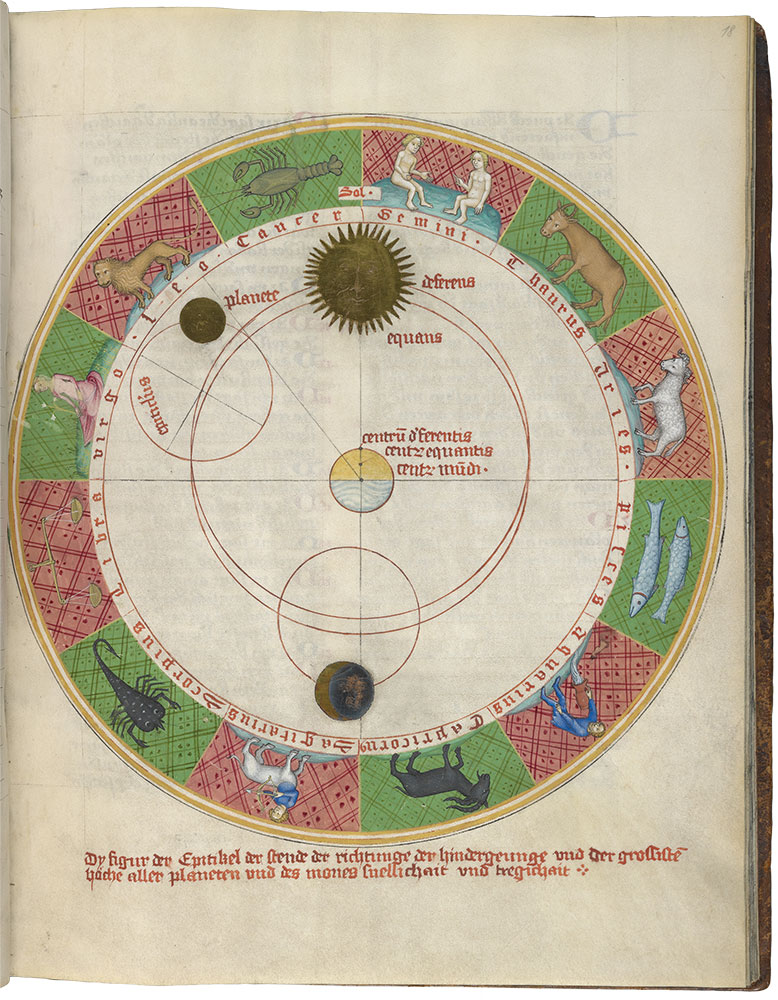

Cosmic Spheres

People in the Middle Ages understood that the world was round, as explained in De sphaera mundi (On the Sphere of the World) by Johannes de Sacrobosco, who taught mathematics at the University of Paris. His fame rests on this widely read astronomical treatise, which incorporates findings of earlier astronomers, including Islamic scholars, leaders in the field. Sacrobosco’s text covers the spherical nature of the universe, as well as planetary motion and eclipses. It also describes the heavens as observed from various points on the earth’s curved surface. A full-page miniature enhances this German translation of the Latin work. Earth is shown at the center of the universe, orbited by the sun, moon, and other planets. The border features the twelve signs of the zodiac.

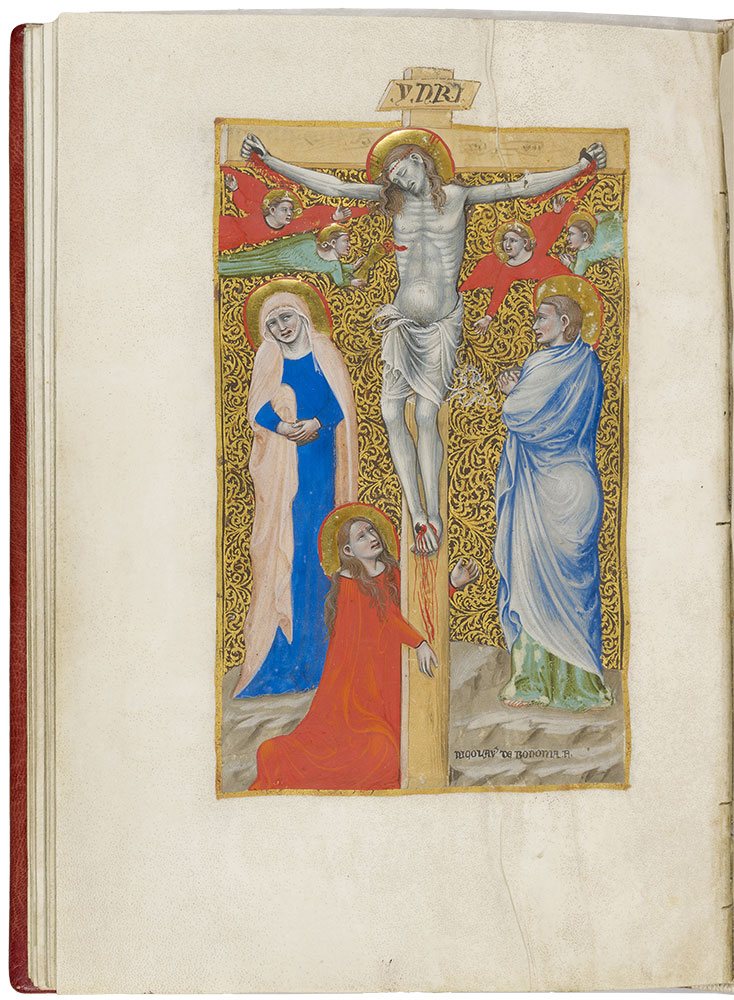

Witnesses at the Crucifixion

This church-service book was painted by the prolific illuminator Niccolò da Bologna. It contains a painting of the Crucifixion, believed by Christians to have saved humanity from eternal damnation. Christ’s gray, emaciated body is flanked by his grieving mother, Mary, and one of his disciples, John. Mary Magdalene, a repentant sinner and friend of Christ’s, kneels at the base of the cross. Medieval artists rarely signed their works, but Niccolò inscribed his signature to the right of Mary Magdalene, perhaps aligning himself with her penitent spirit. On the facing page, the decorated initial T, the first letter of the prayer that begins “Te igitur clementissime pater” (You, therefore, most merciful father), shows a priest celebrating Mass, the commemoration of Christ’s death.

Other items on view drawn from the Morgan’s Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts include a rarely-seen set of twelve trenchers in their original box, bearing the date 1595. These painted circular tablets, made from sycamore, were associated with the royal household of Queen Elizabeth I and would have been used to serve after-dinner delicacies. A collection of five tales known as the Khamsa by the medieval Persian poet Niẓāmī Ganjavī is also on view as well as a Flemish miniature of saintly mothers, illuminated by the Master of the Lübeck Bible and associates.

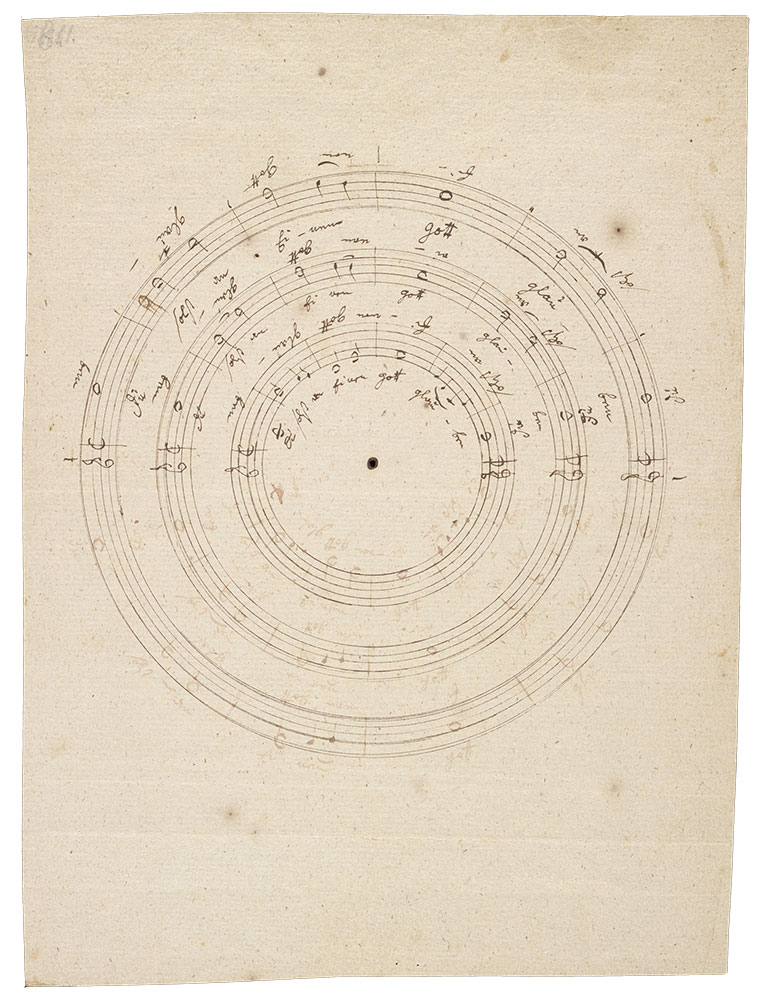

Haydn Entertains His Friends

It is unusual that a body of fifty-six pieces by one of the best-known European composers would remain almost unheard of and rarely performed. This, however, is the fate of Haydn’s unaccompanied choral canons. Perhaps they remain obscure because he generally composed them for himself or close friends, not for public consumption. This manuscript opens the first set of ten canons, each devoted to one of the biblical Ten Commandments. The circular arrangement hints at hidden musical cleverness. The three melodies sound equally harmonious when sung left to right, in reverse, upside down (which changes the pitches of the notes), or in reverse and upside down at the same time. The upside-down version is also legible in the reflection in the lower half of the circle.

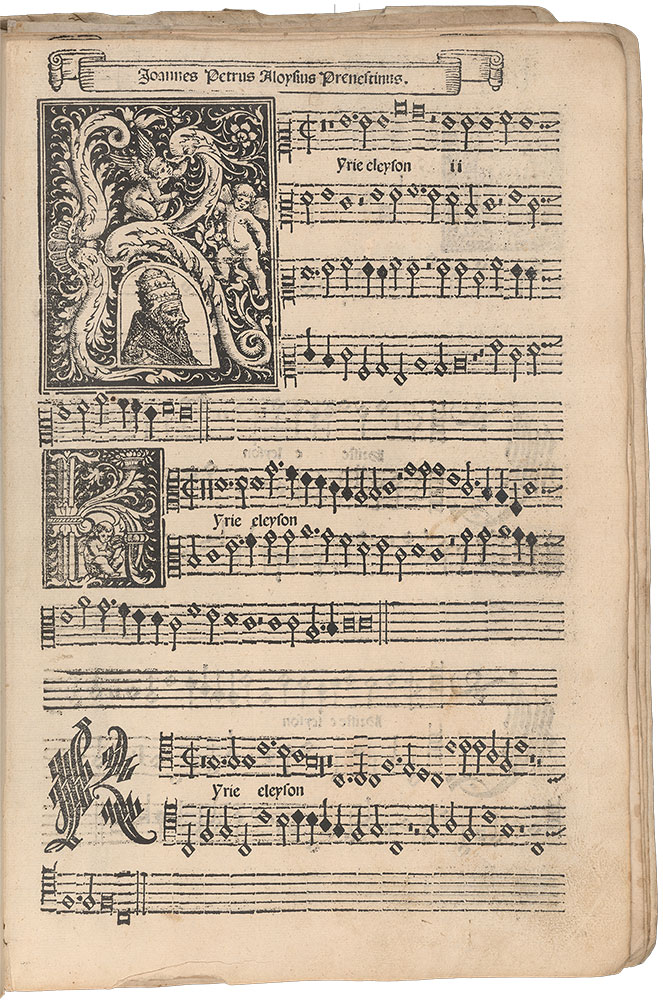

The Music that Saved Polyphony?

When the Catholic Church convened the Council of Trent, the church’s response to the Protestant Reformation, in 1545, among many pressing topics was polyphonic music, in which multiple voices sing different rhythms at once. The council considered banning polyphony, out of concern that the complex music might obscure the meaning of the divine words. According to one legend, this polyphonic Mass by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina on view was so simple and beautiful that it convinced the bishops to not ban polyphony after all. The real story is more complicated, but the facts remain: polyphony stayed, and this famous Mass has been performed often in churches and concert halls ever since.

Musical highlights in this rotation also feature autograph manuscripts by Franz Schubert (1797–1828) and Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), printed music for Les fanfreluches de l’amour by Jane Vieu (1871–1955), one of the few women active as orchestral conductors in the twentieth century; and the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in G Minor, op. 80 (piano reduction) by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912), written during the last year of the composer’s abbreviated life.

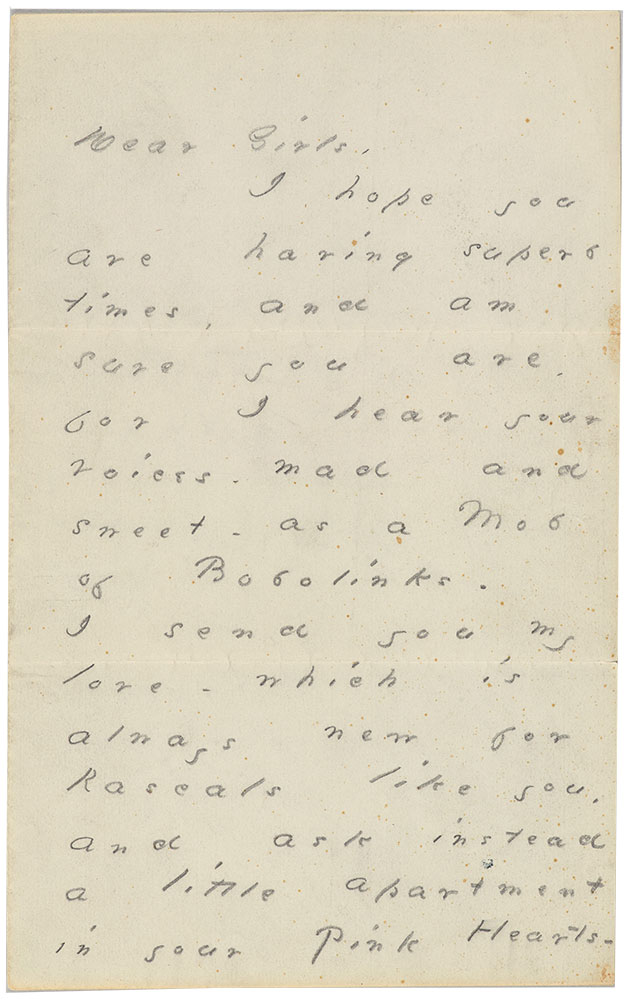

I Hear Your Voices

In this letter Dickinson sends a warm and imaginative greeting to her niece, Martha “Mattie” Dickinson, and family friend Sally Jenkins. By 1883 Mattie and Sally were teenagers, but the poet knew them from earlier days when they presided over a group of local children who played at the Dickinson family home in Amherst, Massachusetts. “I hear your voices—mad and sweet—as a Mob of Bobolinks,” Dickinson writes. “I send you my love—which is always new for Rascals like you.” In a cryptic metaphor referencing the biblical Witch of Endor, Dickinson imagines the girls’ love for her occupying “a little apartment in your Pink Hearts—Call it Endor’s Closet.” She ends the letter with a poem:

If ever the World should frown on you—he is old—you know—give him a Kiss, and that will disarm him—if it don’t—tell him from me,

Who has not found the Heaven—below—

Will fail of it above—

For Angels rent the House next our’s,

Wherever we remove—

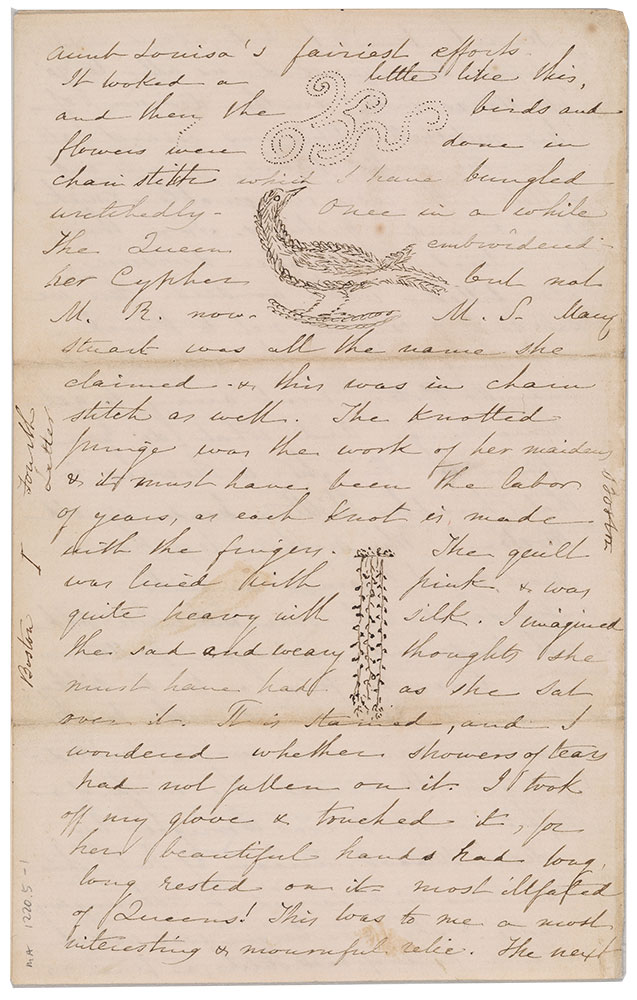

Inspired by the Queen’s Quilt

American artist Sophia Hawthorne and her sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, are regarded today as the “American Brontës” for their contributions to literature, education, and culture. Penned while Sophia traveled in the United Kingdom with her husband, novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, this letter is one of many she sent home to their daughter Una during that overseas trip. The letters would later be published as Notes in England and Italy (1869). On this page, illustrated with drawings of a bird, an arabesque design, and a “curious knotted fringe,” Sophia describes viewing a quilt made by Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587). Alongside the letter are implements that Sophia used in her own needlework.

In addition to Dickinson and Hawthorne, selections from the Morgan’s Literary and Historical Manuscripts include an 1868 inscription by abolitionist Charles Calistus Burleigh (1810–1878) in a friendship album, calling Americans to action: “The abolition of slavery is a victory,” he wrote, “but also the catalyst for future battles to expand enfranchisement, secure women’s rights, and pursue equality before the law for all.” Also featured is a cross-written letter by a teenage Anna Sewell, the author of Black Beauty, and emotional love letter from Arthur Laurents (1917–2011) to the dancer and choreographer Robert Pagent.

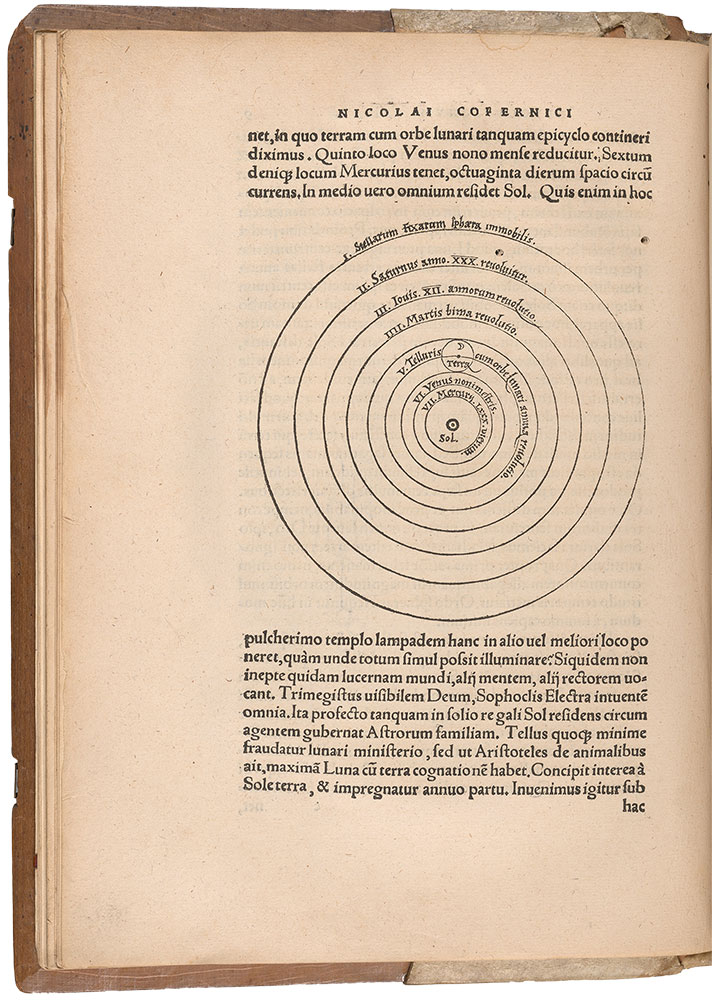

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolutions of the heavenly spheres), Nuremberg: Johannes Petreius, 1543. Purchased in 1934; PML 30647

As the World Turns . . .

The Polish astronomer Copernicus was the first European to argue that the earth revolved around the sun. This contradicted the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic models, which placed a stationary earth at the universe’s center. Copernicus’s measurements relied heavily on the data of Islamic astronomers and mathematicians, including al-Battānī (ca. 858–929) and al-Urdi (d. 1266). His heliocentric model, however, maintained that planetary orbits were perfect circles, which the Islamic astronomers had already disproven. The book’s first edition, shown here, was not a success: the print run of four hundred copies failed to sell out.

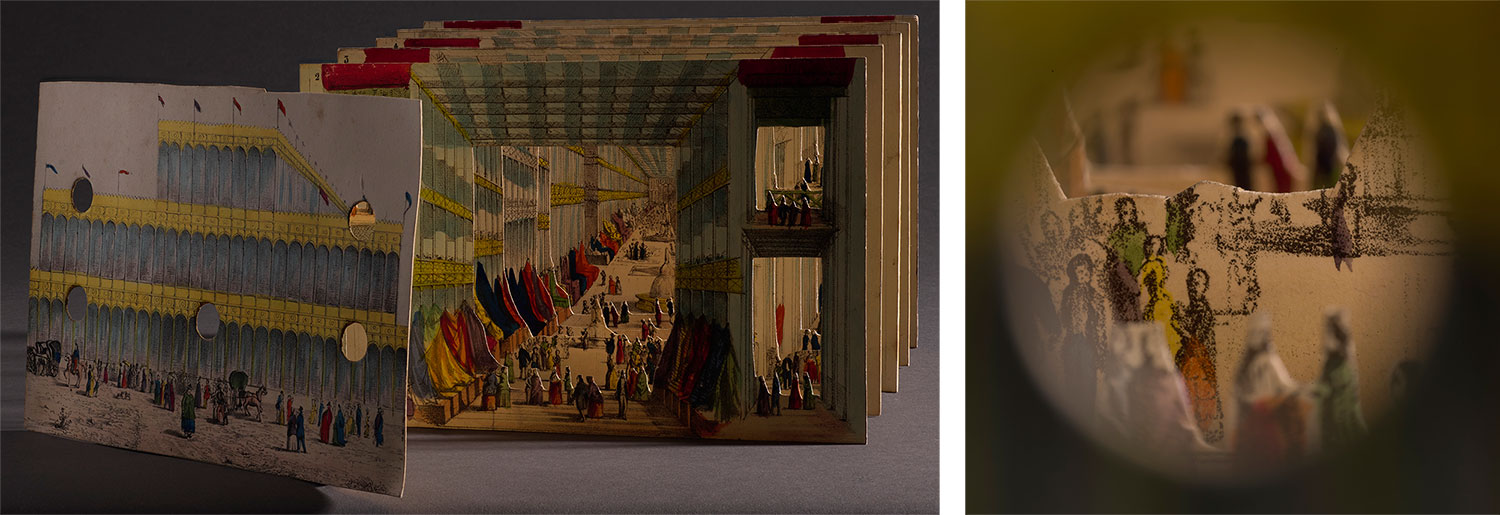

For Your Viewing Pleasure Joseph Paxton (1803–1865), a gardener and architect, was renowned for the glass conservatories he fabricated for the Duke of Devonshire. His fame further grew in 1850 when he designed London’s “Crystal Palace”—the main attraction at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, held the following year. The Hyde Park structure was a monument not only to innovations in glass and steel manufacturing but also to the technological marvels exhibited inside. Merchandise related to the international event was produced all over Europe, including tabletop tableaus for children. These toys, called peepshows, were created from hand-colored lithographs, joined together in an accordion fold or mounted on wooden stands.

Printed Books and Bindings are also represented in two examples of mid-sixteenth-century bindings, Eyn wunderliche Weyssagung von dem Babstumb by Hans Sachs (1494–1576) and Andreas Osiander (1498–1552); poems by Marceline Desbordes-Valmore (1786–1859), whose popular works were read by Baudelaire and Verlaine as children; and a copy of Banjo: A Story Without a Plot by Claude McKay (1889–1948) in a striking dust jacket designed by Aaron Douglas (1899–1979). In the Rotunda, a transposed American flag in etching and aquatint by Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997) orients the reader to the vision of Allen Ginsberg’s poem “America,” included in their collaborative artist’s book La nouvelle chute de l’Amérique (1992).

Collections Spotlight is funded in perpetuity in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker.