After the death of his mother in 1924, J. P. Morgan, Jr., resolved to tear down his parent’s brownstone on the corner of Madison and Thirty-Sixth Street and erect a building adjacent to his father’s library. This new structure, known as the Annex, would allow the institution he founded in his father’s name to serve the public. Morgan wanted to “give the library more room, both for exhibitions and for the work of students,” so he sought to create a spacious interior to meet these goals. He entrusted its design to Benjamin Wistar Morris, the architect who had worked with Pierpont Morgan on the memorial to Pierpont’s father Junius erected at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1910.

Visitors would enter on Thirty-Sixth Street, up a short flight of stairs and through a tall wrought-iron door into the Marble Hall. The richly colored and patterned marble floor paid homage to the inlaid stone pavement in the library’s Rotunda. Opposite the entrance hung a tapestry flanked by torchieres supplied by E. F. Caldwell, the Gilded Age lighting designer who devised all of the fixtures in Morgan’s library. To the left was a gallery for public exhibitions of the collection and at right a Reading Room serving scholars who made appointments to consult rare materials in the collection. To ensure the building was harmonious with its celebrated neighbor, Wistar Morris used the same Tennessee pink marble and his design echoed the library’s austere exterior and more lavishly colorful interior.

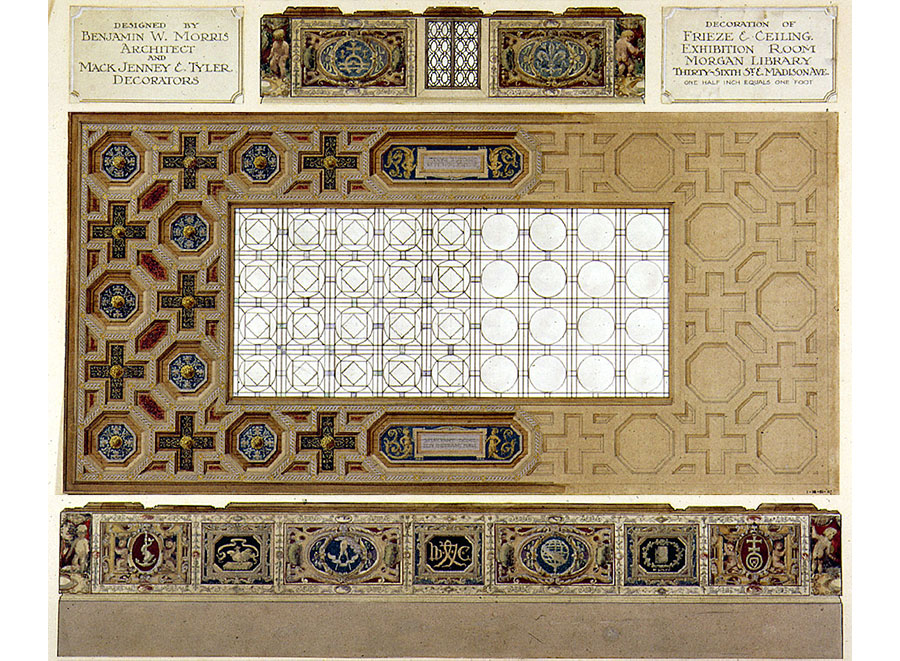

The Marble Hall was a soaring two-story space, with marble columns on the second story interspersed with wrought-iron grillwork by the prominent blacksmith from Philadelphia Samuel Yellin. The Exhibition Gallery featured a painted ceiling and a frieze designed by Wistar Morris in conjunction with the firm Mack, Jenney & Tyler, decorative painters with offices at 15 West Thirty-Eighth Street. The frieze depicted putti in the corners flanking bands of printer’s marks, including the dolphin and anchor first used in 1502 by the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius. Below, on the damask-covered walls, were hung six tapestries from Pierpont Morgan’s collection. Woven in Paris in the early seventeenth century, the tapestries were devoted to the Story of Diana and were probably designed originally for the chateau d’Anet by the French Renaissance master Jean Cousin. The usable wall space was bordered by an elegant cherry dado and frieze, with vertical pilasters dividing the walls into panels. Display furniture of wrought- iron and wood allowed bound volumes to be shown, while walls covered in Belgian linen facilitated the hanging of framed works. The parquet flooring matched that of the East Room in the library, a design also used by McKim, Meade & White in Roosevelt’s White House in 1902.

Exiting the Marble Hall, the visitor encountered a vestibule with windows onto the garden. At the end of the vestibule at right, a door led to a loggia connecting the building to the rear door of the adjacent library to the east. The barrel-vaulted ceiling of the loggia was adorned with grotteschi, in homage to Renaissance loggias and preparing visitors for the transition to Morgan’s library. While decorative painters undertook the work in the loggia, J. P. Morgan, Jr., and Morris summoned H. Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928) the painter who had adorned the ceilings of the Rotunda and East Room for Pierpont Morgan in 1905 to embellish the ceiling of the vestibule. Mowbray was sixty-seven years old.

The appearance of the vestibule ceiling decorations is strikingly different from the paintings in the Library, which were based on Renaissance templates. Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922 fueled an Egyptian revival in America in the 1920s that flourished for decades. This fashionable interest in the subject matter and aesthetics of ancient Egypt and the surrounding “biblical lands” is seen in Mowbray’s Annex ceiling.

The overall theme of the ceiling is a celebration of ancient cultures that contributed to the advancement of human knowledge and Western civilization: the Greeks and Phoenicians, the Persian Emperors Darius and Cyrus, Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III, ancient prophets, and early Christians. Among the scenes and figures represented are Osiris teaching the art of Agriculture and Darius installing the postal service. Such subjects were well-suited to a building dedicated to sharing the Morgan’s collections with the public and facilitating scholarship on collection items. Mowbray completed these paintings shortly before his death on 13 January 1928. The J. Pierpont Morgan Library first opened its doors to the public later that year on 1 October 1928.

Jennifer Tonkovich

Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator

The Morgan Library & Museum