My feeling was the world might get better if I put up my protests. Even if it didn’t, it was just something I had to be doing.

—Purvis Young1

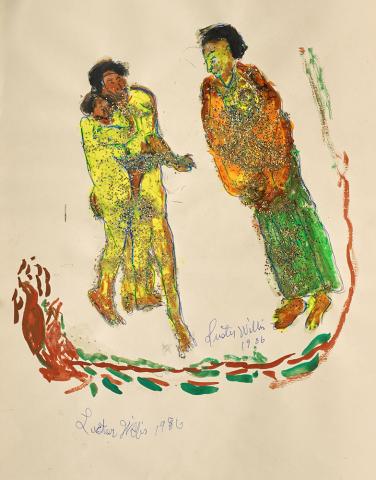

Luster Willis (1913–1990), Standing Together, 1986, paint, glitter, glue, ballpoint pen, pencil, on paper, 20 x 12 1/4 inches (50.8 x 31.12 cm). Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund, 2018.105. © 2020 Estate of Luster Willis / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Two years ago, the Morgan added to its collections a group of eleven drawings acquired from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, whose mission is to preserve and disseminate the work of self-taught African-American artists from the Southeastern United States. Beginning in 2014, the foundation approached cultural institutions to initiate gifts and purchases that would increase public access to the art of Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, the quilters of Gee’s Bend, and many more. The Foundation had not at first considered the Morgan, which has traditionally been known for its collections of rare books, medieval manuscripts, and Old Master drawings and prints. Isabelle Dervaux, the founding curator of the Morgan’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Drawings, opened a dialogue with the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in 2017 that resulted in the Morgan’s acquisition of works by Dial, Nellie Mae Rowe, Henry Speller, Luster Willis, and Purvis Young.

When we think of vernacular art from the American South, we may think of elaborate found-object assemblages or colorful patterned quilts, such as those that were featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s extraordinary 2018 exhibition History Refused to Die. Many of the artists included in the collection of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation were only one or two generations removed from slavery and had endured the injustices of the Jim Crow South—injustices that, tragically, persist all around the country today. Created in areas both rural and urban, theirs is an art of material and spiritual salvage, embroidered with West African traditions.

Like assemblages, works on paper—drawings and collages—constitute a significant medium within a tradition of art that prioritizes readily available materials and making do. Unlike other types of art, drawings are relatively inexpensive to produce; they are portable and easy to store. For these reasons and more, drawing has been valued in the Western world for centuries as the most intimate and direct of artistic mediums.

Luster Willis (1913–1990), a World War II veteran from Mississippi, made collages and pictures on a wide range of supports, including school tablets and fabric; the earliest work in the Morgan’s Souls Grown Deep group is a self-portrait on fabric from the 1950s. Willis’s interest in unconventional materials is apparent in Standing Together (1986). Figures sketched in blue ballpoint pen and painted in vibrant shades of brown, yellow, orange, and green are embellished with sprays of gold and multi-colored glitter. Two simply dressed figures huddle together, one with an arm outstretched toward a third, who looks at the pair with a disapproving expression. If there is a request being made, it is unclear if it will be granted. Nevertheless, as Willis’s title suggests, the figures stand together, all without shoes, all under the enchantment of the glitter’s reflected light.

Purvis Young (1943–2010) was part of a younger generation of Black artists in the South. Inspired by the cultural activism of the 1960s and the art of Rembrandt and El Greco, he created a monumental work of street art in Overtown, Miami, by affixing hundreds of painted panels to the wall of an abandoned alley. The alley was called Goodbread, in reference to a bakery that had once been there. It was a casualty of so-called urban renewal, the practice of decimating Black and Hispanic neighborhoods under cover of eminent-domain laws in order to make way for highways, stadiums, and the like. The Morgan acquired from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation a book that Young covered over and filled with his own drawings—an act of reclamation. Called Sometimes I Get Emotion from the Game (early 1980s), the book is an ode to the basketball and football players of Overtown. Over more than a hundred spreads, Young’s players, some rendered in ballpoint pen, others in marker, some dressed in numbered jerseys, some bare chested, transform the found sheets on which they are drawn into ecstatic illuminations.

Pages from Purvis Young (1943–2010), Sometimes I Get Emotion from the Game, early 1980s, ballpoint pen and marker, on paper glued to found book, 12 1/4 x 17 3/4 inches (31.12 x 45.09 cm). Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund, 2018.106. © Purvis Young / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A recurring motif in Young’s work, and one that appears frequently in Sometimes I Get Emotion from the Game, is a figure with arms raised. It is an evocative posture in any circumstance, conjuring the sacrifice of Christ, joyful song or prayer, or an angry cry of protest. In the context of this book in particular, it conveys the sense of hopeful escape that Young and other Black men experienced on the basketball court or football field. This pose has taken on new meaning in recent years as protesters have adopted the slogan Hands Up, Don’t Shoot in response to police violence against unarmed Black men. Tragically, Young’s elegiac art of resistance is as relevant today as it ever was. This is just one of many reasons for us to rejoice that Black art of the American South has rightly taken its place in the canon of Western art history.

1Quoted in William and Paul Arnett, Souls Grown Deep: African-American Vernacular Art, vol. 2 (Atlanta, GA: Tinwood Books, 2001), p. 392.

Rachel Federman

Associate Curator

Modern and Contemporary Drawings