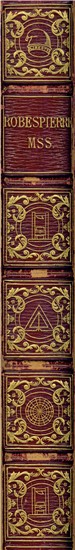

19th century dramatist and collector Victorien Sardou demonstrates a keen understanding of the varying nature of excess during the French Revolution via his meticulous assemblage of manuscripts, letters and engravings. Shortly after Sardou’s death, objects from his collection including a manuscript by Maximilien Robespierre, two pamphlets, three letters, an original pencil sketch and an astonishing fifty-three engravings were mounted in a lavish volume of heavily gold-tooled red morocco by Zaehnsdorf, perhaps as a tribute to the avid investigator of all things revolutionary. The spine, shown here, and the upper and lower boards bear striking symbols of the Revolution, including a guillotine, a Phrygian or “liberty” cap, a triangle with plumb-line to represent perfect balance, and a spider’s web (if anyone has any suggestions as to the web’s significance, please approach the bench).

The manuscript is Robespierre’s portion of a collaboration with Saint-Just against the “indulgent” Dantonists, and its leaves are interspersed with a 19th century pamphlet printed from the text, entitled Project, rédigé par Robespierre, du rapport fait à la Convention Nationale par Saint-Just, contre Fabre d'Eglantine, Danton, Philippeaux, Lacroix, et Camille-Desmoulins (Paris: chez France, Libraire-Editeur, 1841). These are accompanied by another pamphlet printing the report of Saint-Just given at the National Convention against “criminal factions.”

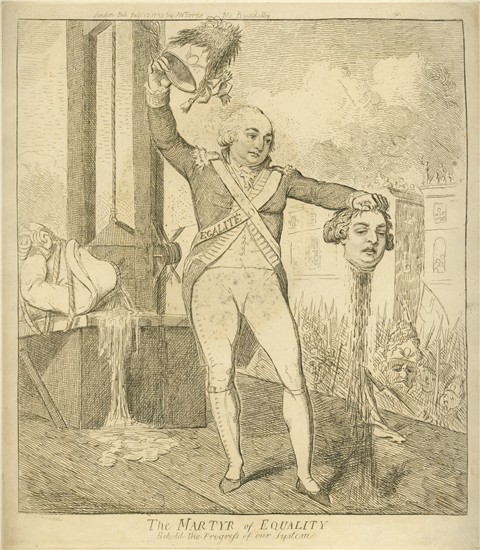

Among the engravings in the collection is this distinctive scene by caricaturist Isaac Cruikshank depicting “Philippe Egalité,” Duc d’Orléans, lifting his hat in a display of kinship to the severed head he grips in his hand. Soon after its publication, Philippe went to the guillotine, as did Danton, Fabre d’Eglantine, Desmoulins and others, during the Reign of Terror, less than a year before the same fate befell Robespierre and Saint-Just. The revolution's momentum and fervor necessarily included the notion of excess, but the indiscriminate axiom of absolute equality eventually pronounced itself on each of these "martyrs" in time.

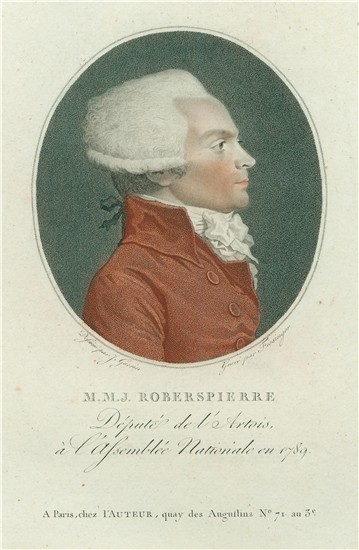

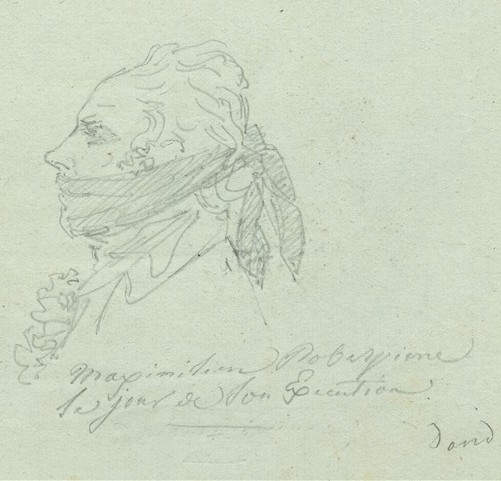

The collection includes many engravings of Robespierre’s unmistakable profile, juxtaposed here with an original pencil sketch attributed to his close friend, Jacques-Louis David.1 The sketch depicts Robespierre on the day of his execution, shattered jaw held in place with a dramatic bandage reminiscent of a gag that would suggest the final silencing of the dictateur sanguinaire. Sardou's dislike for Robespierre is evident in his theatrical works but is perhaps more accurately represented through this collection as a morbid fascination approaching obsession.

For more information on the collection, click here.

1The name David beneath the sketch is not the signature of the artist, but is possibly a mark of identification.

The Leon Levy Foundation is generously underwriting a major project to upgrade catalog records for the Morgan's collection of literary and historical manuscripts. The project is the most substantive effort to date to improve primary research information on a portion of this large and highly important collection.