Last month, browsing the Bonhams auction catalogue Papers & Portraits: The Roy Davids Collection Part II, I came across a description of a three-page manuscript short story by Charles Thomas Clement James (1858–1905), a prolific author whose name and work were completely unknown to me. The story bears the Dickensian title “Concerning the Sinkingsop and Slush Railway” and the footnote accompanying the lot description is amusingly arch: “This manuscript is a fine example, the only one seen commercially, of the remarkable similarity in the handwritings of Charles Dickens and Charles James (of Woodlands, Shorn, by Gravesend, Kent)—indeed so similar are their hands that one suspects some consanguinity, perhaps well outside the prohibited degrees. It is of course well known that Dickens visited ladies in Kent, and Gravesend was the nearest town to Gad’s Hill Place. Railways fascinated Dickens.” As well as impugning the legitimacy of poor old Charles James, the implication is that Charles Dickens was a philandering train-spotter!

According to Charles James, it was Dickens’s eldest son who first noticed the astonishing similarity of handwriting in the early 1890s, characterizing James’s hand as “like a ghost” of his father’s. James does not merit an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, but seems to have been quite a character – he wrote twenty-seven novels and was a double bigamist, for which he served time in Wormwood Scrubs Prison. This fact makes the title of his 1892 novel, Holy Wedlock: A Story of Things as They Are, especially ironic.

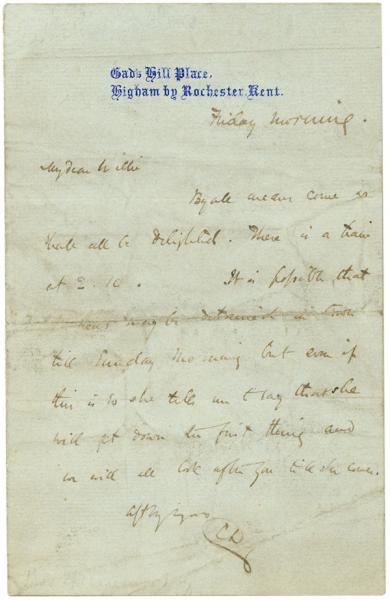

The description of this manuscript, which sold for £1,200 on March 29, reminded me of a one-page autograph letter—really no more than a quick note—in the Morgan’s collection. On the face of it, the letter appears to be by Charles Dickens:

Gads Hill Place,

Higham by Rochester, Kent.Friday morning.

My dear [Wilkie?],

By all means come we shall all be delighted. There is a train at 2.10. It is possible that [illegible] kens may be detained in town till Sunday morning but even if this is so she tells me to day that she will get down the first thing and we will all look after you till she comes.

Affectionately yours

CD

Here's a photograph of the letter:

This letter, donated to the Morgan in 1955 by the famous collector DeCoursey Fales (who established the Fales Library at NYU in 1957 in memory of his father, Haliburton Fales), is accompanied by an undated and unsigned typed commentary titled “Notes on spurious Dickens letter.” These notes dismiss the possibility that the letter is addressed to Wilkie Collins, and cast further doubt on its authenticity by reading “Mrs. Dickens” (from whom Dickens separated in 1859) where the text is obscured and illegible. It could read “Miss Dickens,” of course; Dickens’s daughters resided with him at Gad’s Hill. The note ends sniffily: “this cannot be a letter written by Charles Dickens to Wilkie Collins referring to Mrs. Dickens, whatever else it may be.” But if it is not a Dickens letter then it must be a forgery. This letter has intrigued me ever since I first came across it in the vault, two or three years ago, and my thoughts returned to it after reading the Bonhams auction catalogue.

The editors of the 12-volume Pilgrim Edition of Dickens’s letters seem to have either overlooked this letter, which is most unlikely, given their extremely scrupulous attention to the repositories that preserve the more than 14,000 surviving letters by Charles Dickens, or decided that it is indeed spurious. One feature of this letter that introduces doubt about its authenticity is the ink color—it is written in black ink rather than the more quick-drying blue ink that Dickens began to favor from 1843.

But the nagging question remains: why would someone forge a letter with such quotidian content? The letter is signed only “CD.” If the forger were enterprising enough to obtain blank Gad’s Hill letterhead stationery (the watermark suggests that the stationery dates from around 1859-60) and competent enough to write a brief note of more than passable similarity to Dickens’s own hand, wouldn’t he or she also go to the trouble of forging the famous Dickens signature and flourish to increase its plausibility and add commercial value?

Dickens’s letters were being forged within his lifetime, and he sometimes became aware of some of them; in December 1868 he told his sister-in-law, Catherine Hogarth, that “forgery of my name is becoming popular.” In a 1962 essay on Dickens’s manuscripts, the scholar John Butt pointed out that “one comes across forgeries of Dickens’s letters so clever as to deceive all but the expert.” Perhaps this letter is an example of one of those clever forgeries. What do you think: real or “spurious”?