Security was critical to Pierpont Morgan, especially with his treasures concentrated in a well-publicized, gleaming new building. He took a number of measures to protect the building and its contents, utilizing both a professional security staff and the latest technology. By early 1905, as construction of his library was significantly advanced, Morgan hired a night watchman. As the building reached completion, that position was held by F. William Keogh (1906–7), who was succeeded by H. E. Chapman (1909–10). Morgan placed his trust in individuals, and when the regular mounted policeman on evening duty in the neighborhood was reassigned in 1911, Morgan wrote to Waldo Rhinelander, the commissioner of police, to request the officer be returned to his post. By 1908, supplementing the staff and neighborhood patrol was an electric burglar-alarm system installed by the Holmes Electric Protective Company of New York . The Holmes system was the earliest large-scale alarm system in America and utilized the telephone and telegraph wires in the city. It was activated in the evenings and monitored at a central office by an overnight watchman.

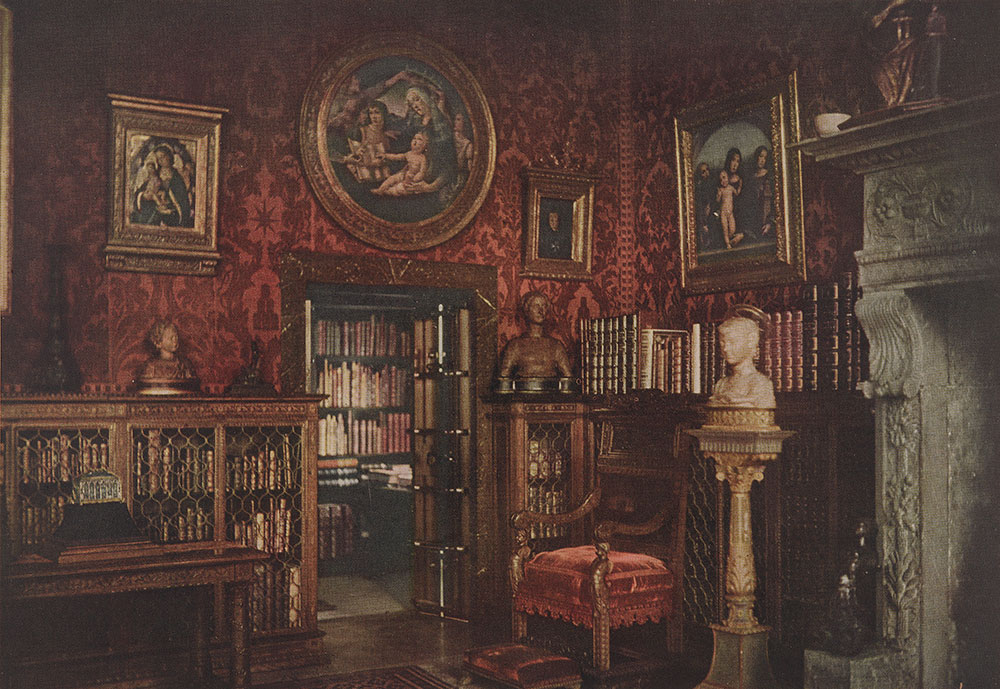

While keeping the building secure from intruders was critical, there were also internal systems developed to protect the invaluable contents of the library. In order to secure the rare volumes Morgan kept in his study, such as the Lindau Gospels, a bank-style steel-lined vault was incorporated into the original design of the room. Apparently at the urging of Morgan's nephew and adviser Junius Morgan, the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White designed a capacious vault that could be concealed behind steel doors covered with simulated-wood paneling. The venerated safe manufacturer Herring-Hall-Marvin of Hamilton, Ohio, produced the combination-locked doors that sealed Morgan’s manuscript vault.

The half-inch-steel lined vault consisted initially of one tier of metal shelving, with a second tier accessed by a rolling ladder; a metal platform and stairs were installed in the 1960s. The vault received natural illumination via a large window on the south end, which, as with all the building’s fenestration, was equipped with a securable bronze fire shutter on the inside and an iron grill on the exterior. This allowed light to enter when the shutters were open but prevented entry through ground-floor windows. Morgan’s stronghold was used to house his cherished medieval and Renaissance manuscripts from 1906 until the museum’s 2003 expansion project. It now contains a selection of the luxurious volumes Morgan commissioned to document his varied collections. The manuscripts and other rare materials are now kept in the museum’s Renzo Piano designed state-of-the-art underground vaults.

Morgan’s interest in security extended to office documents. He requested clever features be built into the custom-designed furniture to allow papers to be kept private. The furniture commissioned from Cowtan and Sons, London, including Morgan’s desk and the desk of his librarian Belle da Costa Greene, contains secret drawers and panels released with hidden springs. These compartments allowed Morgan and Greene to keep small objects, invoices, correspondence, and other sensitive materials confidential despite the activity in the building.

Other clever innovations can be found in the fabric of Morgan’s study, including a secret bookshelf, concealed behind a shallow front shelf, to the left of the fireplace. This hidden shelf contained the more risqué volumes in Morgan’s collection of rare books. It was only accessible to Morgan and his librarian, who could open the bookcase with a key, slide the shallow-front bookcase to the left, and reveal the secret shelf behind.

Although security techniques have evolved, today’s security team continues to safeguard the Morgan’s treasures with pride and tenacity. While most modern security measures, such as cameras and alarms, are discreet and virtually unnoticed by visitors, the Morgan’s security staff has always been the most visible aspect of our efforts to safeguard the collection. When I first started at the Morgan in 1993, I would walk up to the entrance on Thirty-Sixth Street and the great wrought-iron-grilled door would be opened by a guard who welcomed all visitors to the museum. In 2006, the museum’s entrance was reoriented to Madison Avenue, yet every visitor who enters encounters one of our security guards welcoming them, answering questions, or lending a hand. For the staff of the Morgan, entering on Thirty-Seventh Street, each workday begins and ends with a greeting from a member of our security team. All of the security staff remain committed to keeping our collections and campus secure during this period of closure, and when we reopen, they will be at the forefront of making sure our visitors and our holdings remain safe.

Images

Graham S. Haber: figures 3, 5; Michel Denance: figure 4; John Calabrese: figure 6.

Jennifer Tonkovich

Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator

The Morgan Library & Museum