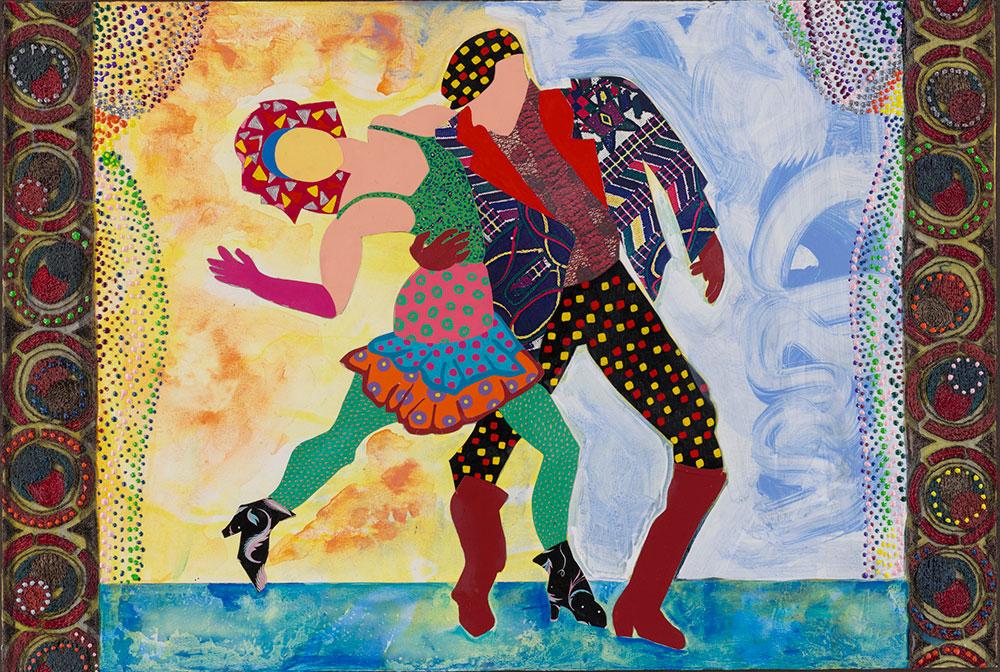

Flamenco (for Rondo), 1988. Acrylic and cut-and-pasted papers on paper, 24 x 18 in. (61 x 45.7 cm). Gift from The Collection of Peter and Kirsten Bedford, 2021.157:8. © 2022 Estate of Miriam Schapiro / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

During the 2021 winter holiday season, the Morgan received as a gift Rondo, a group of twenty-four collages by feminist-art pioneer Miriam Schapiro (American, born in Canada, 1923–2015). The donors, Peter and Kirsten Bedford, commissioned them in 1988 for a series of clothbound artists’ books published under their San Francisco imprint, Bedford Arts. Schapiro’s accordion-folded Rondo (1989) was the second in the series; the first was Roy De Forest’s A Journey to the Far Canine Range and the Unexplored Territory Beyond Terrier Pass (1988). (The Bedfords donated the original art for De Forest’s book to the Morgan as well.)

A rondo is a music and dance form consisting of a main theme that alternates with contrasting themes. The first eleven panels of Schapiro’s Rondo feature dancers, alone or in pairs, most of them set against brightly painted backgrounds. Dance, theater, and costume were significant themes in Schapiro’s art throughout her career. She began to engage more directly with figures of dancers in the years preceding Rondo. In Flamenco, a fiery-haired dancer’s ruffled skirt is represented by cut pieces of black-, yellow-, and cream-colored paper. The torsion of the dancer’s body, silhouetted against a riot of color, lends depth to the “nospace on a nostage” of the collage, as Schapiro refers to it in the book’s colophon. The figure’s extraordinary splayed-fingered left hand both mimics and seems to manifest the profusion of dynamic painted marks that criss-cross the sheet. The next collage in the series is called The Apache. The Apache dance takes its name from a (problematic) moniker for the Parisian underworld in the early twentieth century. The dance for two often takes the form of a violent encounter, though this aspect is less apparent in Schapiro’s interpretation. Unlike the other collages in Rondo, this one clearly situates its subjects on a stage. They are flanked by tied curtains formed from dots of acrylic paint and a proscenium of patterned fabric.

Schapiro came of age as an artist in New York City in the 1950s, during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. She was highly attuned to the air of machismo that permeated the New York School. She noted that her female artist friends, including Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan, rarely discussed their art and ambitions with one another. “Art was somewhat of a secret life when we were together,” she said.1 In the 1960s, she shifted from a gestural style to a hard-edged one. This approach to painting made her at home in California, where she moved in 1967. It was during this time that Schapiro had her consciousness raised and became a leader in the Feminist Art movement. In 1970 she joined the faculty of the illustrious California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. The following year, she co-founded the school’s Feminist Art Program with Judy Chicago and co-created the landmark Womanhouse (1971–72), converting a Hollywood mansion into a showcase of works—some of them immersive installations—by more than two dozen women artists. Schapiro coined the term “femmage” to describe her increasingly tactile works, which, similar to The Apache, combined acrylic and fabric. But it was also a term she sought to apply retroactively to techniques associated with women’s crafts throughout history and across cultures.2 Schapiro’s art was as much about paying homage to artistic forebears, named and unnamed, as it was about creating new forms. She said:

I talk about women's traditional art, the art of women who decorated pots or did the weaving—the great Navajo weaving—the eye-dazzlers of the southwest. Most of the decorative art has been done by women throughout time and civilization. What happened long ago in art criticism was that a distinction was made between high art or fine art and low art or craft/decorative art. And all that craft/decorative/low art which needs a superb sense of color and design has been done primarily by women. So the patriarchal fix in criticism has always made that sexist distinction. What women did in the seventies was to reinvent pattern and decoration as an integral part of high art.3

Fabric Squares (for Rondo), 1988. Fabric on paper, 24 x 18 in. (61 x 45.7 cm). Gift from The Collection of Peter and Kirsten Bedford, 2021.157:12. © 2022 Estate of Miriam Schapiro / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Fabric Squares, the twelfth panel of Rondo, is simply a swatch of red-and-black- checkerboard fabric adhered to a sheet of paper. Schapiro’s straightforward gesture opens onto a multiplicity of meanings. Dance floors are often made from a black-and-white- check pattern. The pattern also references the game of chess, famously beloved by Marcel Duchamp, the French artist who pioneered the readymade in art. Fabric Squares further evokes the grid form adopted by artists ranging from Piet Mondrian in the 1910s to Sol LeWitt in the 1960s. But alongside and above these landmarks of twentieth-century modernism, Schapiro’s appropriation of the pattern points to a much longer, largely anonymous, history of quilting. The Feminist Movement ushered in a wave of recognition for the cultural and artistic value of quilts. Writing in 1982, critic and curator Lucy Lippard observed, “What is popularly seen as ‘repetitive,’ ‘obsessive,’ and ‘compulsive’ in women’s art is in fact a necessity for those whose time comes in small squares.”4

This economical collage acts as a hinge between the first part of Rondo, which is dominated by dancers, and the second, which features twelve collages of “images on a flat plane … still—not in motion—as if the dancers on the front had caught themselves concentrating on one thought, one image,” as Schapiro writes in Rondo. Collectively, these collages are a kind of rebus of Schapiro’s motifs since the 1970s: hearts, kimonos, masks, flowers, fans, and an homage to Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), a Russian avant-garde artist who championed folk forms. In Bouquet, Schapiro plays with the viewer’s expectations by using a printed image of lace that is easily mistaken for the real thing. One cannot help but think of Georges Braque’s use of wood-patterned wallpaper in Fruit Dish and Glass (1912), considered by many to be the first Cubist collage. Schapiro took umbrage at the notion, perpetuated by mainstream art histories, that Braque and Picasso “invented” collage.

Like Bouquet, Double Fan, with its prominent representation of leaves, references the long history of collage, which includes cut-paper flowers and botanical specimens pasted into albums, primarily by women. Schapiro adopted the fan as a major motif in the late 1970s. She told an interviewer, “the fan lends itself to a certain kind of structure. You have radiating out of a center twelve struts […]. When I was beginning those I wanted to ‘heroicize’ the fan which was considered […] a coy device to attract a man. What women do with romance is always considered very trivial in society. I wanted to make an iconic statement […] saying look, go take your beliefs and shove them because we've got a whole set of different ones.”5 The circular fans here resemble African hand fans. They support a range of images related to the decorative and the domestic: a house, a dress, an urn, a cup, and even another fan. Schapiro placed a printed image of an African mask between the fans’ handles, likely a reference to the role such masks play in danced ceremonies. Beneath it, she pasted a Victorian-era illustration of the Brothers Grimm tale Hansel and Gretel. Showing the moment when the children meet the witch who seduces them with candy, this ambivalent signifier may point to any number of themes.

This blog post takes its subtitle, “Let’s Dance,” from the eponymous track of a 1983 David Bowie album. The song’s video, filmed in the tiny Australian town of Carinda, features Indigenous Australian teens and was intended by Bowie as a statement against racism. Using her distinctive techniques and formal syntax, Schapiro seeks in the exuberant and joyful Rondo to unleash the power of dance as a liberatory force against patriarchal and other forms of systemic oppression.

Rachel Federman

Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- Thalia Gouma-Peterson, Miriam Schapiro: Shaping the Fragments of Art and Life, exh. cat. (Lakeland, FL: Polk Museum of Art, 1999), 35.

- Schapiro wrote about femmage in an issue of the feminist journal Heresies that was focused on traditionally female crafts around the world. Miriam Schapiro and Melissa Meyer, “Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage,” Heresies , Vol. 1, no. 4: Women’s Traditional Arts, The Politics of Aesthetics (Winter 1977–1978): 66–69.

- Christy Sheffield and Enid Shomer, “An Interview with Miriam Schapiro,” Women Art News, Vol. 11 (Spring 1986): 24.

- Lucy Lippard, “Up, Down, and Across: A New Frame for New Quilts,” in Charlotte Robinson, ed., The Artist and The Quilt (New York: Knopf, 1982), 32.

- Sheffield and Shomer, 23.