What do you expect to see when you come to the Morgan? Rare books and master drawings? Cherished names like Austen, Tolkien, and Babar? Modern art, or contemporary photography? How about music?

It turns out that the first half of that list is more likely than the second. A recent survey showed that relatively few visitors think of the Morgan as a place for modern art or photography, despite our deep collections in those domains. And less than a quarter expect to see a music exhibition when they visit the Morgan.

As music curator, I hope to increase that number. In this two-part series, I’ll guide you through some favorite highlights from our exceptional music holdings. The music collections at the Morgan are vast and deep, varied and surprising, handwritten and printed, very old and very new. They span more than a millennium of musical creativity. Proceeding chronologically, we will witness the history of notated music ranging from its beginnings in the medieval period to its modern practice. We’ll see rare autograph music manuscripts of the great classical composers, unique early-edition printed scores, personal letters of famous musicians, and more.

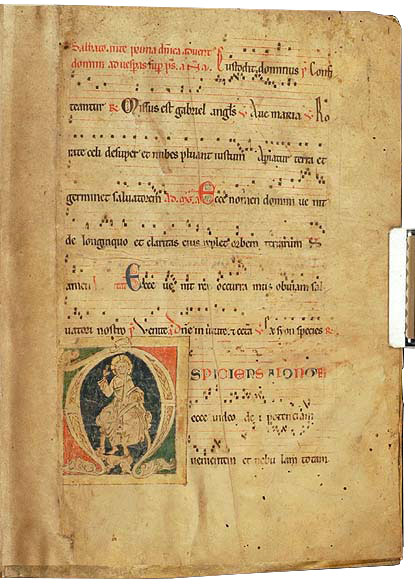

Let’s begin with a quick visit to our Department of Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts. Music in these collections dates back to the eighth century. Some manuscripts are three feet tall, many inches thick, and bound with imposing wood and metal bindings, needing two people to carry them safely. Here are two beautiful examples showing early square-note music notation.

Created by several scribes in France or Germany around 1200, this antiphonary of chants sung for Cistercian use covers the liturgical year from Advent through the Sundays after Pentecost. Here we see a chant for the First Sunday of Advent, the beginning of the liturgical year.

More about this manuscript »

This gradual, a type of service book, was written and illuminated in Florence, Italy, in the monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli between 1392 and 1399. This page shows the Introit for the Third (main) Mass on Christmas Day, with a gorgeous illustration of the holy family in the stable.

More about this manuscript »

Jumping forward three centuries, we come to the Morgan’s Department of Music Manuscripts & Printed Music, the domain I am lucky to work in.

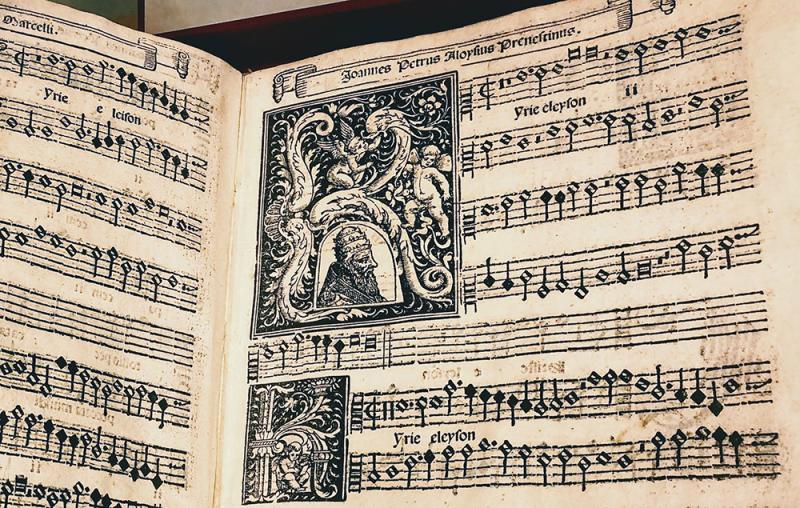

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525/6–1594), “Missa Papae Marcelli” (Pope Marcellus Mass), In Missarum liber secundus (Masses, book 2), first printing, 1567, James Fuld Collection

This score holds a special place in my affection: our first edition of Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass, printed in 1567 under the composer’s watch. A choral setting of the Roman Catholic mass, this music found instant fame during the composer’s lifetime. It appears in college music history textbooks as a crowning example of sixteenth-century polyphonic music. A legend emerged, only partly true, that this piece saved the art of polyphony from a ban by church leaders at the Council of Trent.

This work resides in one of the key parts of the music holdings at the Morgan: the James Fuld Collection, the world’s finest repository of first-edition printed music. James Fuld (1916–2008) spent his life collecting rare editions spanning almost five centuries, from the first-ever printing of “Three Blind Mice” in 1609, to first-edition Beethoven scores, to songs by Cole Porter and Stephen Sondheim. Scores in the Fuld Collection are often accompanied by programs, photographs, and other objects that bring the world of the composer vividly to life—including interesting items like postage stamps of Charles Ives and Claude Debussy. The book of carefully documented melodies that Mr. Fuld created from this collection, The Book of World-Famous Music, makes for wonderful reading—and humming.

Fuld is just one of several major music collections housed at the Morgan. A quick word about these collections will orient us as we continue.

Our founder, J. Pierpont Morgan, didn’t show a great interest in collecting music, but his eye for quality set the stage for his library’s future reputation as an important center for music. He purchased Mozart’s earliest letters, and in 1907 acquired the manuscript of Beethoven's Violin Sonata no. 10 in G Major, one of our most cherished works.

In the 1960s, two important collections of autograph music manuscripts came to the Morgan. The Heineman Collection is small but wonderful, featuring beloved music like Chopin’s Polonaise in A-flat, op. 53. Much larger and equally wonderful, the Mary Flagler Cary Collection arrived in 1968, putting the Morgan on the map internationally as a center for music scholarship. The Cary Collection features manuscripts of the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, including important works like Mozart's "Haffner" Symphony, Schubert's Winterreise, and Schoenberg’s Gurre Lieder, which we will see in Part II of this tour. Our Cary and Morgan holdings also include a large number of early-edition printed scores.

The Robert Owen Lehman Collection is every bit the equal to the Cary Collection. It is a privately owned collection, held on deposit at the Morgan since 1972. Thanks to Mr. Lehman’s generosity, we are able to make items in this collection available, by permission, for exhibitions and scholarly study. Among many other treasures, the Lehman Collection contains one of the largest collections of Ravel manuscripts anywhere, along with a wealth of Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg works (Pierrot Lunaire stands out). The Cary and Lehman collections complement one another with matching reserves of Mozart and Mahler manuscripts, making the Morgan a primary center for the study of those two composers.

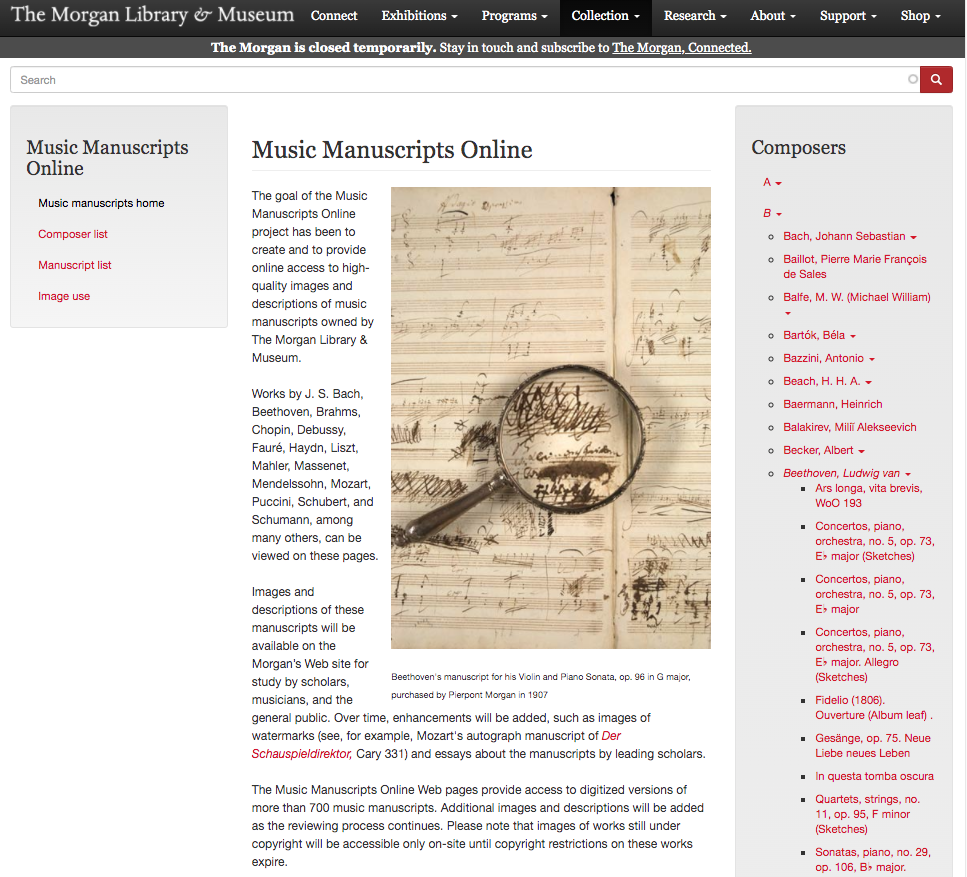

Seven hundred music manuscripts, more than half the total, are available as full digital facsimiles on our website at Music Manuscripts Online, an image of every page in vivid detail. Even those manuscripts that have not yet been digitized appear regularly in exhibitions. All of the music materials at the Morgan are searchable in our online library catalog and are available by permission for digital imaging and for scholarly study in person in our Reading Room.

You can see that we take pride in these manuscripts. But part of the reason for this tour is to show that music at the Morgan goes far beyond them. Our rare early- and first-edition printed scores are even more numerous and varied, and many are unique, annotated in the hand of their composer or by other well-known musicians. We’ll see a few samples during this tour.

Our collections include many further riches as well: One of the world’s great Gilbert and Sullivan collections, seven thousand letters of famous composers and other musicians, a wealth of Italian opera scores and related materials, and much more. I invite you to read full descriptions of all the music collections at the Morgan in our Researchers' Guide.

Let’s continue on our chronological journey. I will show you not only the more famous works, but some lesser-known gems as well, to demonstrate the variety and depth of music at the Morgan. I hope to capture a bit of how it feels to wander the vault with a curator, examining interesting items as they catch the eye. Each one has a story to tell.

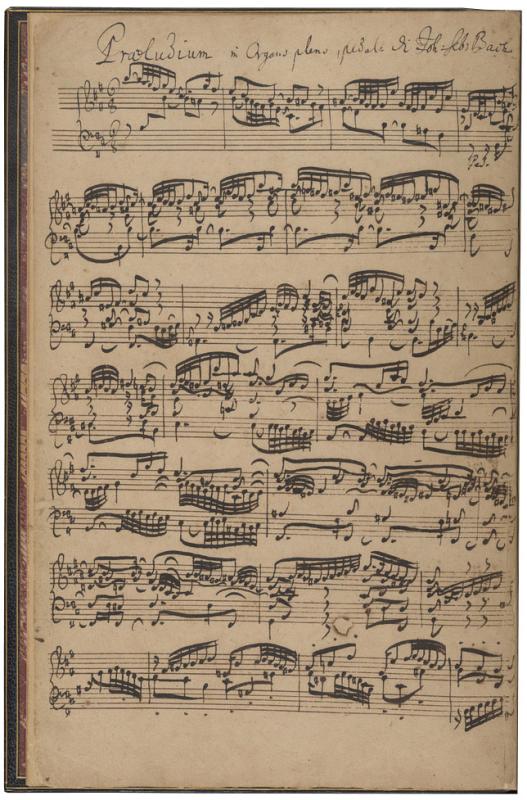

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Prelude and fugue for organ in B minor, BWV 544, Autograph manuscript, between 1727 and 1731, Robert Owen Lehman Collection, on deposit.

I’d like to indulge you with two contrasting scores by Johann Sebastian Bach. First, one of the most visually beautiful autograph manuscripts at the Morgan, in the Lehman Collection on deposit: Bach’s Prelude and fugue for organ in B minor, BWV 544, completed in 1731. Bach’s loopy, elegant hand is beautifully demonstrated here. And as you’ll see in the video, it takes all four limbs to play this music.

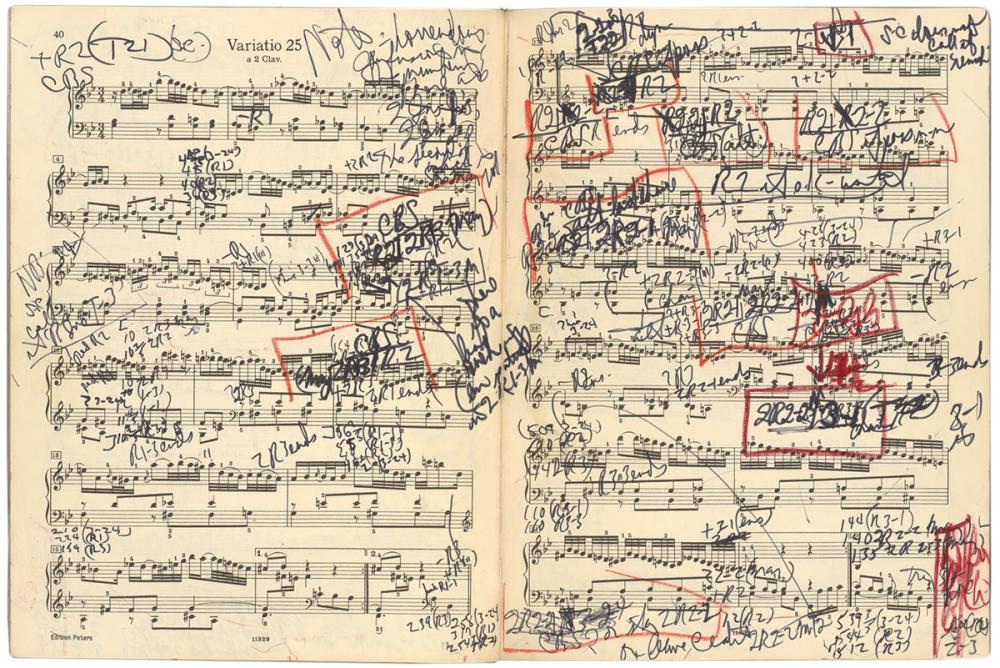

While Bach achieved only modest fame during his lifetime, by the twentieth century he had come to be seen as an essential icon of European culture. The twentieth-century pianist Glenn Gould was known for his series of correspondingly iconic recordings of Bach’s keyboard works. For his second recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, on CBS Records in 1982, Gould marked the score heavily to show which audio takes he wanted to include.

The Mary Flagler Cary Collection is the cornerstone of music at the Morgan. Mrs. Cary’s correspondence with dealers and rare-book sellers tells the fascinating story of a discerning collector at work, during the middle of the twentieth century. One of her regular sources was Walter Schatzki, who ran a rare-book store on East Fifty-Seventh Street in New York. In a 1956 letter to her, upon delivery of the manuscript of Franz Schubert’s string quartet “Death and the Maiden,” which she had purchased—and which is now in her collection at the Morgan—Schatzki wrote:

The quartet is one of the most fascinating manuscripts I have ever seen. It shows almost in every line the compulsive urge of the creative mind at work and in the quick flow of the handwriting it reminds me of your manuscript of Beethoven’s Geistertrio [also at the Morgan].

Let’s put his claim to the test by comparing the slow movements of both works that he mentions:

These two complete manuscripts are easily at your fingertips on our website (along with all manuscripts in the Cary Collection except those still under copyright), so I invite you to scan through the complete scores: Schubert here and Beethoven here. Taking in an entire work, page by page, gives that sense of the flow of the pen that Walter Schatzki wrote about.

In the case of the Beethoven “Ghost” Trio manuscript that I just mentioned, you will find that the composer tried and rejected four different endings for the middle movement, before settling on the one he published. I explored those five endings in my recent video tour of Beethoven manuscripts at the Morgan, along with his sketch for the “Hammerklavier” Piano Sonata Op. 106 (also on our website, of course).

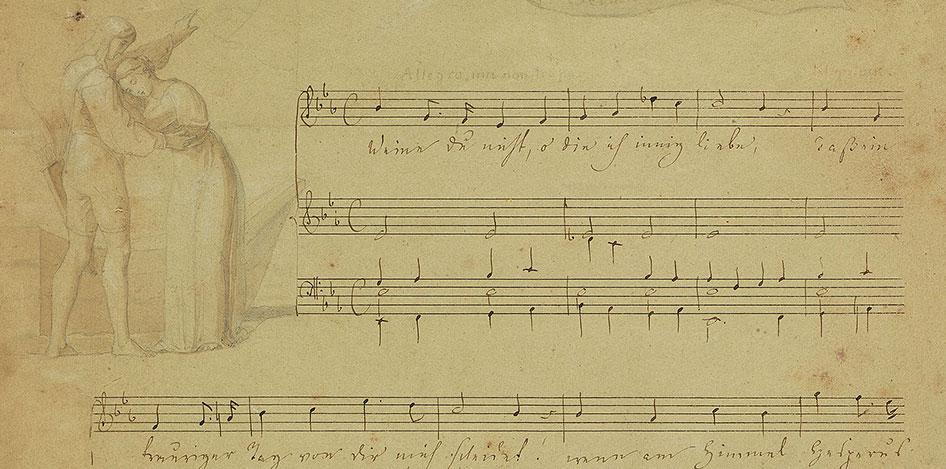

The words of this song by Fanny Hensel tell of a fictional sister’s fear for the safety of her brother as he embarks on a perilous ocean journey. Fanny wrote the song as her brother and fellow composer Felix Mendelssohn, with whom she was close, was preparing to set sail for London. In this later copy of the song, Fanny’s husband Wilhelm Hensel, a portrait artist, illustrated the score with a touching image of a sister and brother embracing. You can see the complete manuscript here.

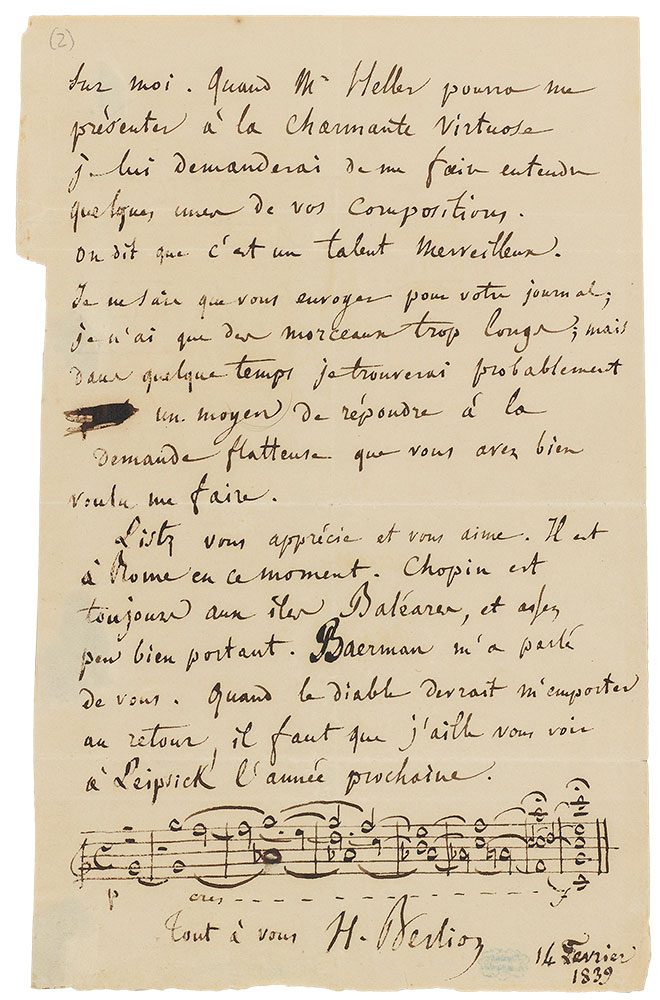

Across several music collections at the Morgan, you will find a wealth of letters, written to and from many of the composers in the collections, and many other musical figures. Around the same time that Hensel was composing her song of imminent departure, the French composer Hector Berlioz was writing from Paris to his fellow composer and music critic Robert Schumann, urging him to visit Paris. Berlioz’ salesmanship was a bit lacking, however, in that he describes his city this way: “There are few honest young men worthy of the name of artist, and many gnomes and a lot of morons and above all scoundrels (you see that I observe the law of crescendo).” Perhaps to emphasize his crescendo of epithets, Berlioz added this otherwise unidentified musical fragment, a swelling series of harmonies.

For fans of the English comic opera duo Gilbert and Sullivan, the Morgan is a heaven on earth: the world’s largest archive of this kind, formed by Reginald Allen, who brought it to the Morgan in 1949. In our vault you will find over 20,000 items, including piano-vocal scores, librettos, acting editions, music manuscripts, letters, programs, playbills, photographs, posters, cigarette advertisements with H.M.S. Pinafore product placements, and a great deal of other memorabilia. Particularly touching to me are the boxes of letters composer Arthur Sullivan wrote to his mother, almost daily for many years. As a sign of the depth of this collection, we have not only that correspondence itself, but additional family records including this Sullivan genealogy written by his mother, Mary C. Sullivan.

That brings us to the end of the nineteenth century. In Part II of this tour through the music collections at the Morgan, we will move into the twentieth century and its many riches.

Robinson McClellan

Assistant Curator of Music Manuscripts and Printed Music

The Morgan Library & Museum