In 2024 the Morgan celebrated 100 years of being a public institution, and many of the museum’s supporters honored that event by donating works of art to the collection. For the exhibition, A Celebration: Acquisitions in Honor of the Morgan’s Centennial, each curatorial department (except Ancient Western Asian Seals & Tablets, which is not currently acquiring material) selected about ten to twelve gifts and promised gifts made to commemorate the anniversary. Because of this individual selection process, there is no overarching subject or theoretical framework uniting the material: it is an exhibition of independent works. However, as the curator charged with managing the exhibition and departmental contributions, I started to see connections between the various works from around the museum, and I briefly toyed with the idea of creating discrete thematic groupings. These groups, unfortunately, were not sustainable across the entire selection, nor were they, of course, the only way to connect this material. Ultimately, these groups seemed more limiting than helpful, and we decided to lay the exhibition out chronologically to maintain the individuality of the works. Below is a selection of the theme groupings that were initially considered.

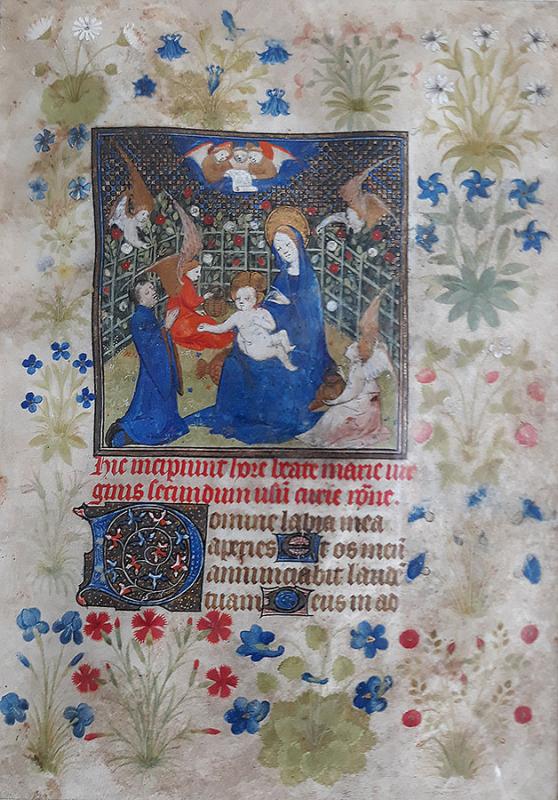

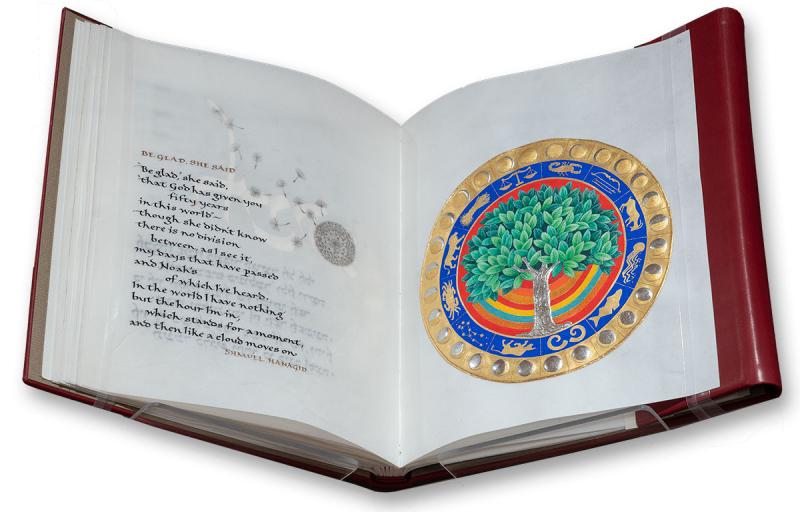

In chronological terms, the department of Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts holds the honor of having both the earliest and most recent objects in the exhibition: a manuscript leaf produced in Paris around 1418 and Barbara Wolff’s illuminated A Tent for the Sun from 2024, which was created in line with medieval artistic traditions.

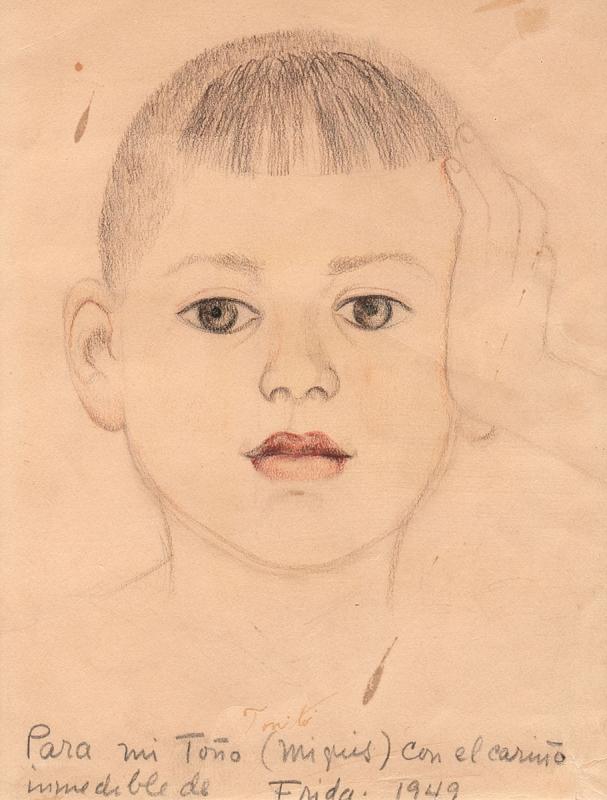

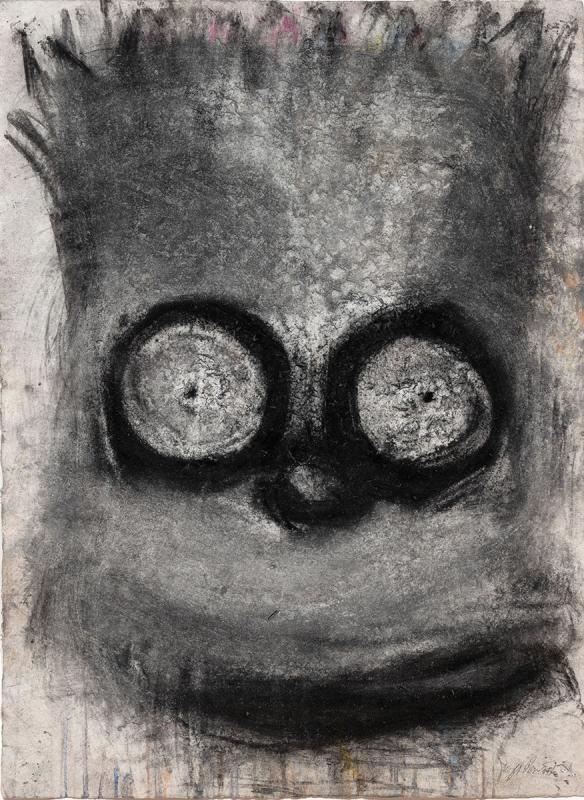

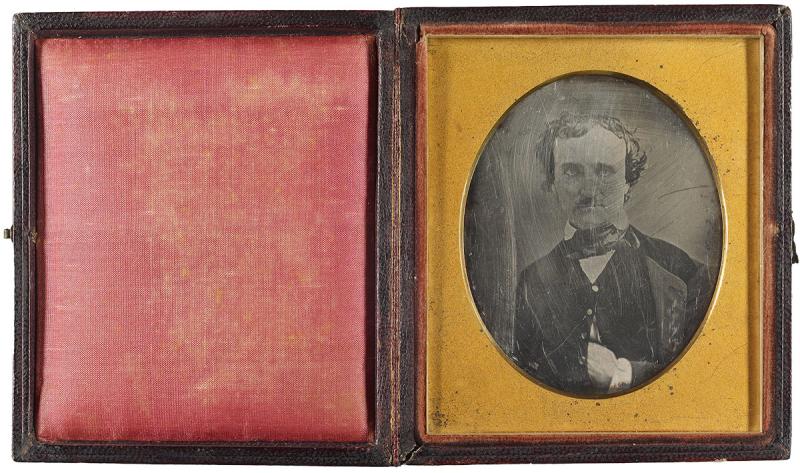

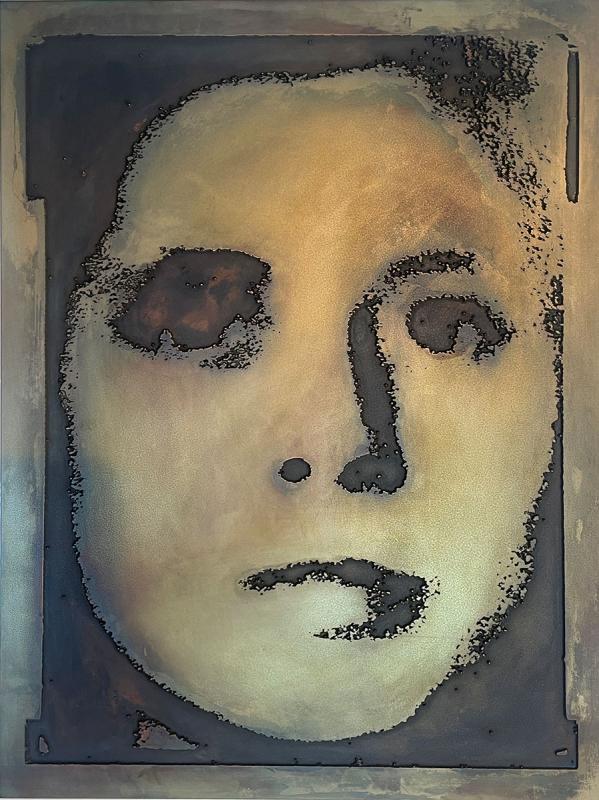

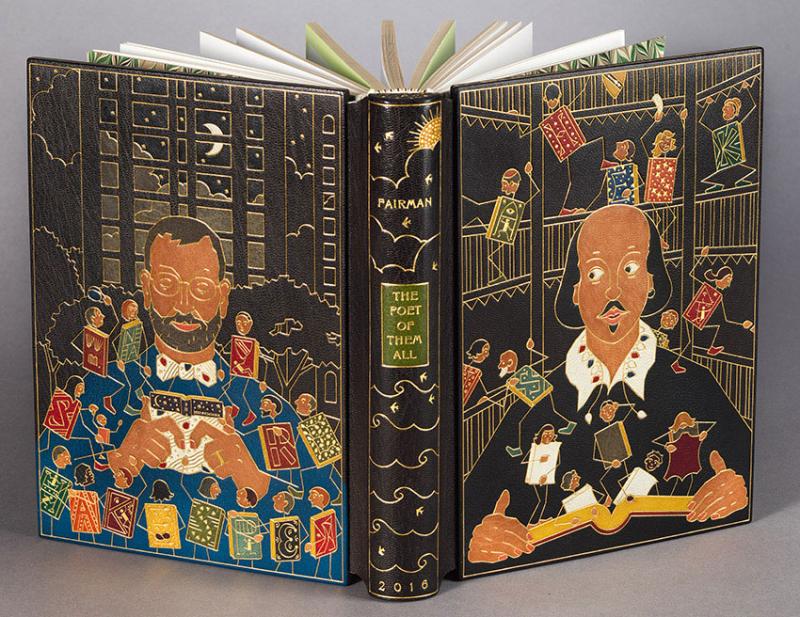

One of the groupings that immediately jumped out was portraiture. Perhaps the most prevalent genre of Western art, there were plentiful examples across the collections. Frida Kahlo’s tender portrayal of her nephew, Antonio, and Joyce Pensato’s almost aggressive image of Bart Simpson both directly confront the viewer with their forward gaze (as do many other examples). The daguerreotype of Edgar Allen Poe and Naomi Savage’s Mask, both also intent on the viewer, showcase the relationship between portrait and photographic processes, though they were produced 100 years apart. Giovanni Battista Capocaccia’s wax and stucco relief portrait of Pope Pius V and Theodosio Fiorenzi, in a frame designed to resemble a bookbinding, and Michael Wilcox’s bookbinding depicting William Shakespeare and the collector Neale Albert, both sit at the intersection of mixed media and sculpture.

Michael Wilcox (Canadian, b. Britain, 1939–2023). Colored goatskin leather bookbinding on “The Poet of Them All”: William Shakespeare and Miniature Designer Bindings from the Collection of Neale and Margaret Albert, 2016. Promised gift of Neale and Margaret Albert in honor of the Morgan’s Centennial.

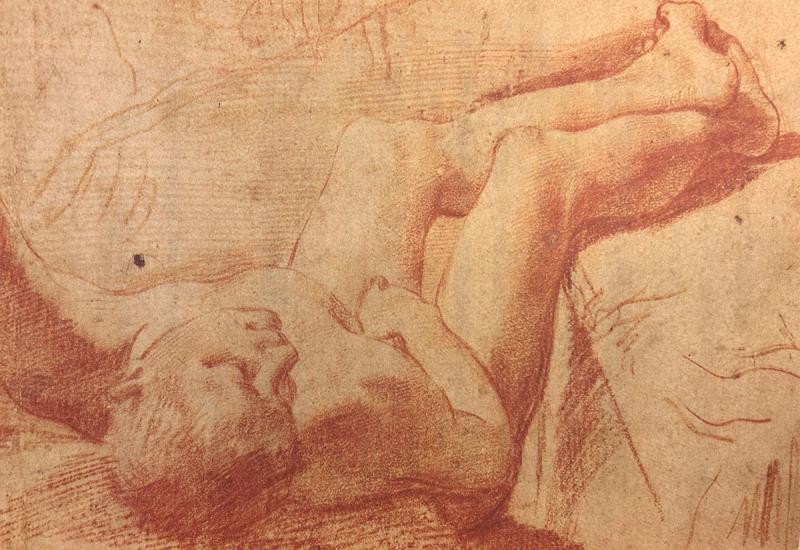

Closely tied to portraiture is the Renaissance practice of portraying the physical form in three dimensions. Artists have long grappled with naturalistic representation, and Leonardo da Vinci made copious notes on the process, which his assistant, Francesco Melzi, preserved. Melzi organized these notes to create Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting, which was copied in numerous manuscripts in the seventeenth century. One of the copies presented to the Morgan was likely owned by Roland Fréart, sieur de Chambray (1606–1676), who translated the text to French for the first printed edition of Leonardo’s work. This same interest in three-dimensional naturalism is reflected in the reclining boy by Annibale Carracci and the swirling mass of Hercules and Antaeus by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, both revealing how artists conceived of compositions in three dimensions.

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (Italian, 1727–1804). Hercules and Antaeus, with the Hydra Below, ca. 1770–90. Promised gift of Alyce Williams Toonk in honor of the Morgan’s Centennial.

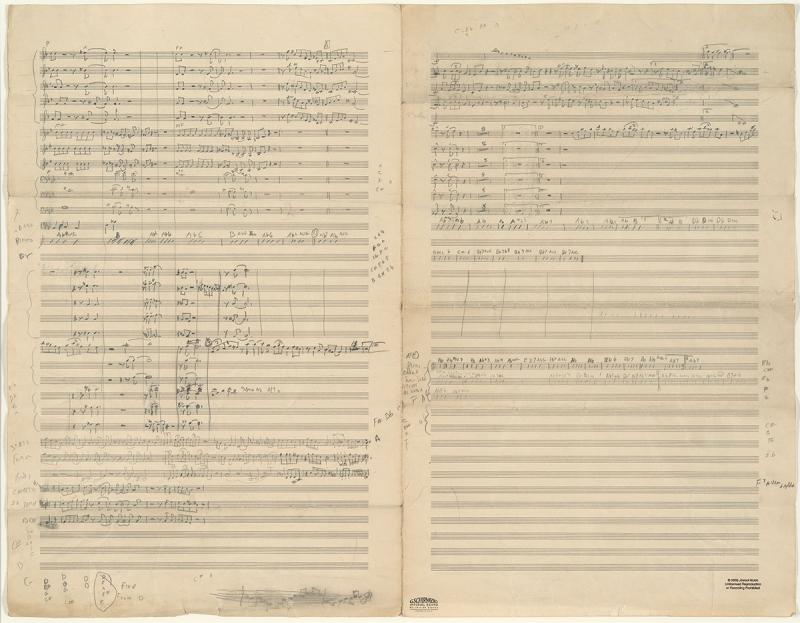

The creative concept of the “draft” is intimately tied to the Morgan’s collection and encompasses both the more typical textual draft but also artist’s working sketches, like the Carracci drawing. Belle da Costa Greene had a particular interest in draft manuscripts that revealed the creator’s process and preferred them to the often more legible “fair copy” manuscripts, such as the Leonardo text above. Jazz great John Coltrane’s notational snippets and drafts reveal his learning process with nascent bebop, while François-René de Chateaubriand’s biography shows him revising an earlier draft in his secretary’s neat handwriting, in preparation for publication.

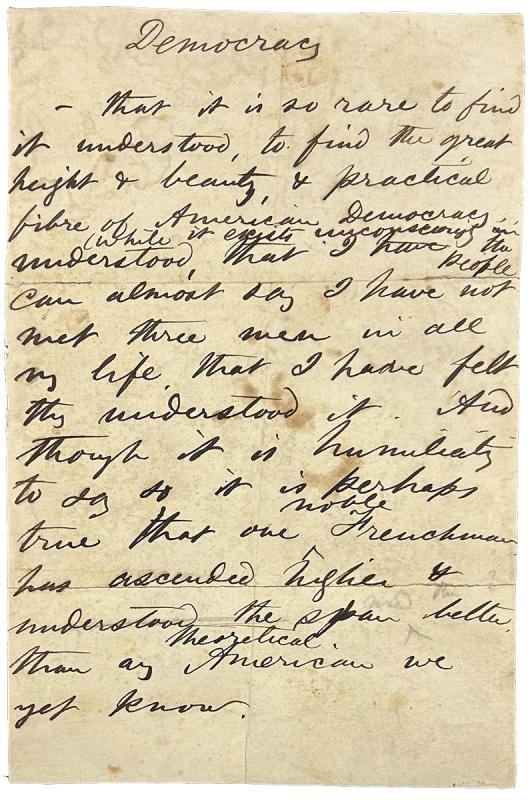

A third draft option is Walt Whitman’s edited excerpt, “Democracy — that it is so rare to find it understood…,” from his essay Democratic Vistas, which provided a political segue to Richard Minsky’s book sculpture series on the Bill of Rights.

While the above groupings are perhaps unsurprising and expected—rather traditional themes—when looking at the individual departments’ selections, I was surprised to find several works with compositional connections. These three works by Paul Cezanne, Thomas Hart Benton, and Deborah Turbeville share a common theme—bathers—but even more striking are the resonances in the visual structuring of each work and poses of individual figures. Benton may as well have been reducing the Cézanne to its basic geometric forms as he did the Renoir, while Turbeville seems to be recalling both for her Vogue fashion shoot.

These are only a few examples that I thought of in the exhibition, and I look forward to seeing the ways in which visitors to the exhibition make their own connections in our collections.

John T. McQuillen

Associate Curator of Printed Books & Bindings

The Morgan Library & Museum