These playlists open the Morgan’s music collections to your ears. The one rule is that every track is a piece of music that we hold, in physical form, in the Morgan’s vault—either a unique manuscript or a rare print edition. With thousands of scores both handwritten and printed, spanning six centuries of musical creativity, the Morgan’s collections offer plenty of playlist possibilities.

New playlists will be added in the future, so please check back.

We invite you to explore the music collections at the Morgan. Search our online collection catalog or browse a list of highlights (PDF).

- Famous and Lovely Music from the Morgan’s Collections

- Great American Songs in the James Fuld Collection

- Philip Glass: Einstein on the Beach

- Frédéric Chopin and Scott Joplin

- Shakespeare in Music

- Beethoven and Bridgetower: A Famous Sonata

Famous and Lovely Music from the Morgan’s Collections

This playlist offers a sampling of highlights from the vast riches held in the music collections at the Morgan Library & Museum. Browse highlights of our music holdings here (PDF).

Great American Songs in the James Fuld Collection

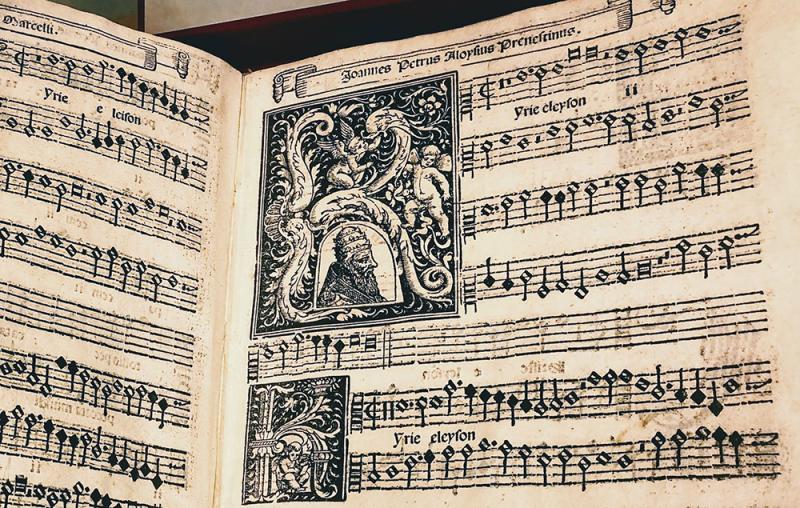

You know the Morgan for our classical music, but do you know our superb collection of classic popular songs? The James Fuld Collection at the Morgan is one of the world’s largest repositories of first-edition printed scores, from the earliest printings of Three Blind Mice (1609) and Silent Night (1832) to rare editions of music by composers from Palestrina to Beethoven to Ives. Mr. Fuld’s collection contains many well-known classical and popular melodies, which he compiled in his wonderful Book of World-Famous Music.

This playlist gathers classic tunes in the James Fuld collection written by American composers between 1850 and 1950, featuring the likes of W.C. Handy, Harold Arlen, and Mildred J. Hill (never heard of her? I guarantee you know one of her songs by heart). A nice thing about popular songs is their huge variety of different arrangements in widely contrasting styles. That’s how this playlist manages to include not only glorious mid-twentieth century voices like Etta James, Judy Garland, and Nina Simone, but also the more recent renditions by Michael Jackson and... Bill Murray (yes, Bill Murray).

The flip side of that variety of versions is that Spotify credits the performer most clearly in the track listing, often failing to mention the composer. So we’ll list the composers here, each with the relevant rare edition in the Morgan’s James Fuld collection (plus one manuscript in the Mary Flagler Cary collection). Lyrics are by the composer unless otherwise noted.

| Track 1 | Get happy by Harold Arlen (1905–1986), words by Ted Koehler. Possible first edition, inscribed by the composer to James Fuld. New York: Remick Music Corp., c1930. |

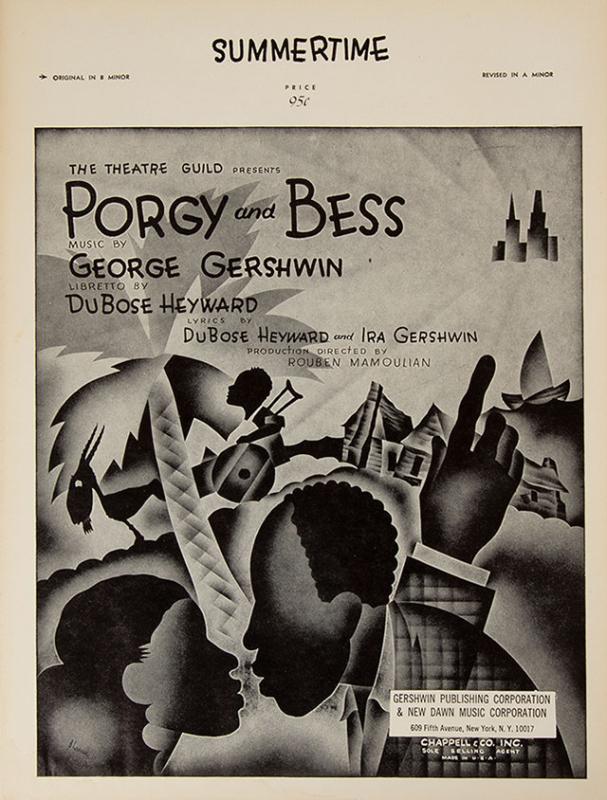

| Track 2 | Summertime by George Gershwin (1898–1937), words by Du Bose Heyward. First edition. New York: Chappell & Co., Inc., c1935. |

| Track 3 | Begin the beguine by Cole Porter (1891–1964). Possible first edition, signed by the composer. New York: Harms Inc., c1935. |

| Track 4 | Over the rainbow by Harold Arlen (1905–1986), words by E. Y. Harburg. Probable first edition. New York: Leo Feist, Inc., c1939. |

| Track 5 | In the evening by the moonlight by James A. Bland (1854–1911). New York: Hitchcock Pub. Co., c1880. |

| Track 6 | (When your heart's on fire) Smoke gets in your eyes by Jerome Kern (1885–1945), words by Otto Harbach. First edition. New York: T.B. Harms Co., c1933. |

| Track 7 | All the things you are by Jerome Kern (1885–1945), words by Oscar Hammerstein. First edition. New York: T.B. Harms Co., c1939; 1940. |

| Track 8 | St. Louis blues by W. C. Handy (1873–1958). New York: Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc., c1914. |

| Tracks 9–10 | Swing low, sweet chariot arranged by J. R. Murray, in "Songs of the Jubilee Singers from Fisk University". Cincinnati: John Church & Co., c1881. |

| Track 11 | Deep river, arranged by Harry Thacker Burleigh (1866–1949). Composer's manuscript, 1926. View the manuscript in our repository of digitized works, Music Manuscripts Online. |

| Track 12 | Jeanie with the light brown hair by Stephen Foster (1826–1864). First edition. New York: Firth, Pond & Co., c1854. |

| Tracks 13–14 | She’ll be comin’ round the mountain and He’s gone away, in the American songbag, compiled by Carl Sandburg. First edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., c1927. |

| Tracks 15–16 | [“Happy Birthday” in] Song stories for the kindergarten by Mildred J. Hill (1859–1916). Earliest printing of the tune that later became “Happy Birthday to you” (originally “Good-morning to all”). Chicago: C.F. Summy, c1893. |

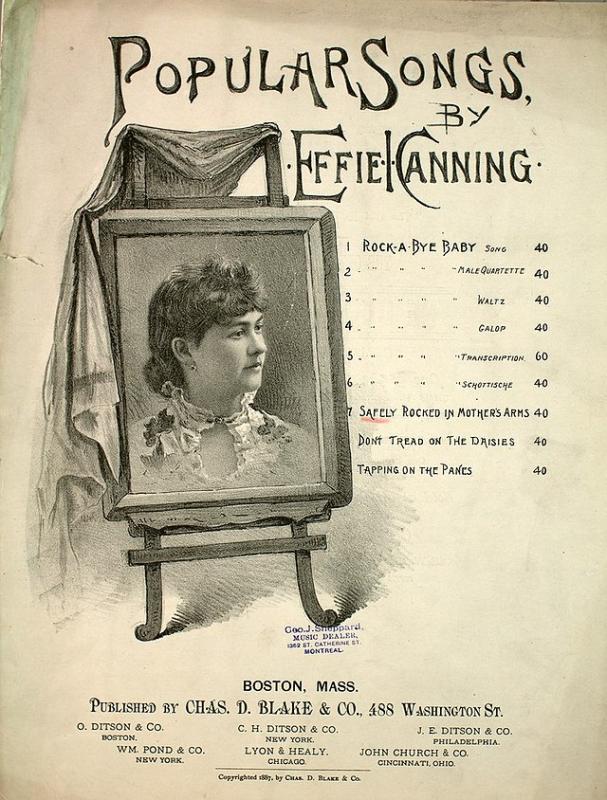

| Track 17 | Rock-a-bye baby: song & lullaby by Effie I. Canning (1857–1940). Possible first edition. Boston: Chas. D. Blake & Co., c1886. |

Philip Glass: Einstein on the Beach

The Morgan is lucky to hold the complete original manuscript of the world-changing 1976 opera Einstein on the Beach, by Philip Glass. In tandem with a 2012 revival of the opera at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Morgan mounted an exhibition devoted to the work, showing the entire manuscript along one wall.

Frédéric Chopin and Scott Joplin

The Morgan holds fifty rare editions of Scott Joplin’s sheet music and a significant collection of Frédéric Chopin’s manuscripts and first editions. In a sheet music advertisement written around 1904, Joplin's publisher John Stark compared the two composers:

[Joplin’s] ‘Maple Leaf Rag’... is played by the cultured of all nations and is welcomed in the drawing rooms and boudoirs of good taste. [Joplin’s] 'The Cascades' … is as high-class as Chopin.

In similar vein, Joplin historian Bill Ryerson writes that "Joplin did for the rag what Chopin did for the mazurka."

There are striking parallels between the two composers. Both wrote mainly for the piano, often featuring graceful melodies over um-pah left-hand accompaniment. Both drew on folk traditions and dance rhythms, and both became national icons in their homelands. Both thrived on improvisation and struggled to capture the flow of music within the static confines of music notation. Both belonged to marginalized groups, in different ways: Chopin as a Polish immigrant in Paris, a group then often viewed with suspicion; Joplin as the son of an enslaved person in post-Civil-War America. Both died before age fifty from diseases much more common in their time (tuberculosis and syphilis).

Do these two composers really belong together, as John Stark suggested? This playlist serves to test the hypothesis; each listener will be the judge. Choosing the tracks required special care: matching each track to a manuscript or printed score held at the Morgan, I chose pieces of similar length for the sake of balance, about five minutes each. The tracks alternate, Chopin - Joplin - Chopin - Joplin, each answering the one before, making the playlist a dialogue across time between two composers whose lifetimes didn't overlap, a joining of cultures and idioms.

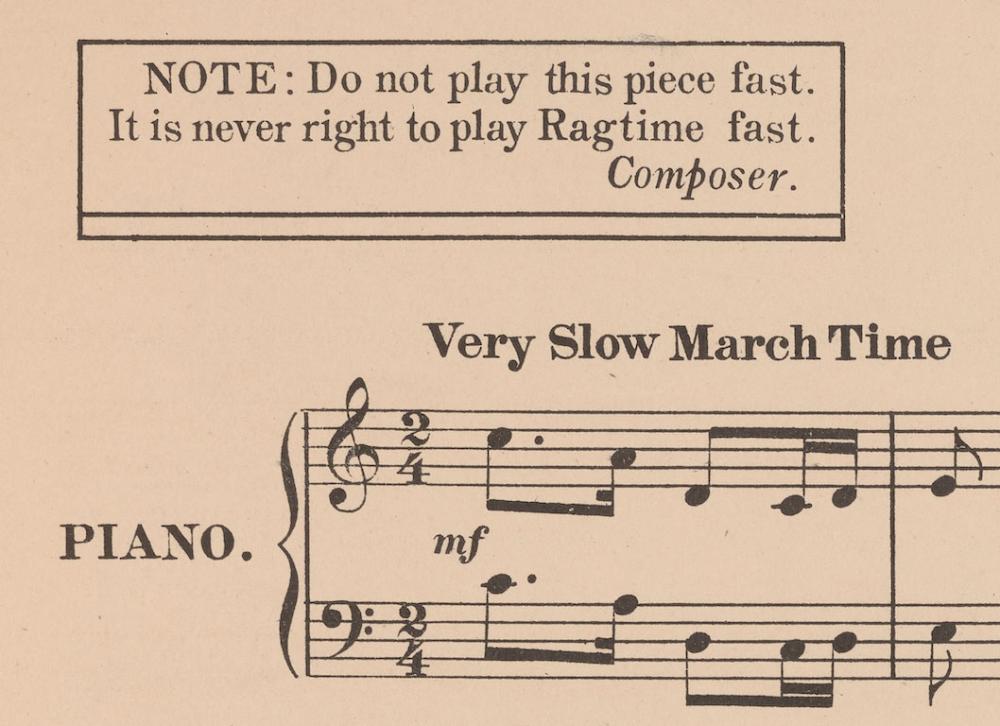

While Chopin’s music is represented on this playlist by several different pianists, for Joplin’s music there is just one: William Appling. To me, Appling’s renditions are special, revealing the music in a new light and bringing out Joplin’s intricacy and lyricism. Aiding this are Appling’s tempos, slower than what one usually hears. He takes particular care to observe the direction Joplin placed emphatically at the top of his scores, that “it is never right to play Ragtime fast.”

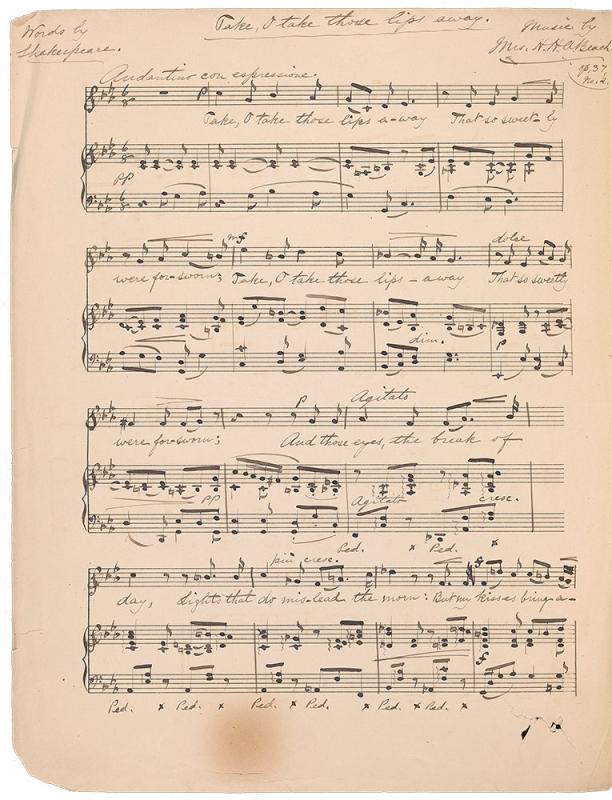

Shakespeare in Music

This playlist takes a journey through music inspired by the words of William Shakespeare. The focus is on manuscripts, rather than printed scores: Every piece in this playlist exists in the Morgan’s collections as a unique handwritten artifact.

Beethoven and Bridgetower: A Famous Sonata

Go, my dear B, at about noon today to Count Deym’s . . . where we both were the day before yesterday. . . . I can’t be there until about half past one. Until then . . . I take pleasure in merely thinking of you. Your friend, Beethoven

Written today, this letter might have been a text message, a quick scheduling note between two young friends. It was May 1803, and Ludwig van Beethoven wrote to George Bridgetower, a violinist of gathering fame recently arrived in Vienna. The warmth of the letter also infused the new piece Beethoven wrote for his friend, a sonata for violin and piano, Opus 47, designed to showcase Bridgetower’s extraordinary skills. In the dedication to Bridgetower, Beethoven called the composition “sonata mulattica,” a reference both to the violinist’s African and European parentage and to the unorthodox musical blend of major and minor, sonata and concerto.

The name this famous work bears today, the Kreutzer Sonata, has little to do with the friendship that inspired it. After quarrelling with Bridgetower, Beethoven changed the dedication to honor Rodolphe Kreutzer, a French violinist he had only met briefly years before, who called the sonata “unintelligible” and never played it.

This playlist opens with the riveting first movement of the sonata, then moves to other music by Beethoven that captures the story around his friendship with Bridgetower. To learn more about the story watch our IGTV broadcast. For more, the Google Arts & Culture Project on Beethoven includes two videos about Bridgetower presented by Chi-chi Nwanoku, a double bass player at the Royal Academy of Music. Here she introduces the story, and here she speaks with Randall Goosby, the young violinist who has been performing the sonata recently to great acclaim.

Robinson McClellan

Assistant Curator of Music

The Morgan Library & Museum