Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, “This Lime-tree Bower my Prison,” is an extended meditation on immobility. Lamed for a few days in a household accident, Coleridge took the opportunity to write about what it is like to stay in one place and to think about your friends traveling through the world. When he wrote the poem in 1797, Coleridge and his wife Sara were living in Nether Stowey, Somerset, near the Quantock Hills. William and Dorothy Wordsworth had recently moved into Alfoxton (sometimes spelled Alfoxden) House nearby, and Coleridge and Wordsworth were in an intensely productive and happy period of their friendship, taking long walks together and writing the poems that they would soon publish in the influential collection Lyrical Ballads (1798). Dorothy Wordsworth was also an essential member of these gatherings; her journals, one of which is held by the Morgan, were another expression of the constant exchange, movement, and reflection that characterized the group.

In July 1797, the young writer Charles Lamb came to the area on a short vacation and stayed with the Coleridges. Charles had met Samuel when the two were students at Christ’s Hospital in the 1780s. Samuel was three years older than Charles, and he encouraged the younger man’s literary inclinations. Charles is the dedicatee of “This Lime-tree Bower,” in which Coleridge imagines his friends going out on a walk without him, over a heath, into a wood, and then out onto meadows with a view of the sea. Meanwhile, the poet, confined at home, contemplates the things in front of him: a leaf, a shadow, the way the darkness of ivy makes an elm tree’s branches look lighter as twilight deepens. He writes about the rewards of close attention:

“Yet still the solitary humble-bee

Sings in the bean-flower!

Henceforth I shall know

That Nature ne'er deserts the wise and pure;

No plot so narrow, be but Nature there,

No waste so vacant, but may well employ

Each faculty of sense, and keep the heart

Awake to Love and Beauty! and sometimes

'Tis well to be bereft of promis'd good,

That we may lift the soul, and contemplate

With lively joy the joys we cannot share.”

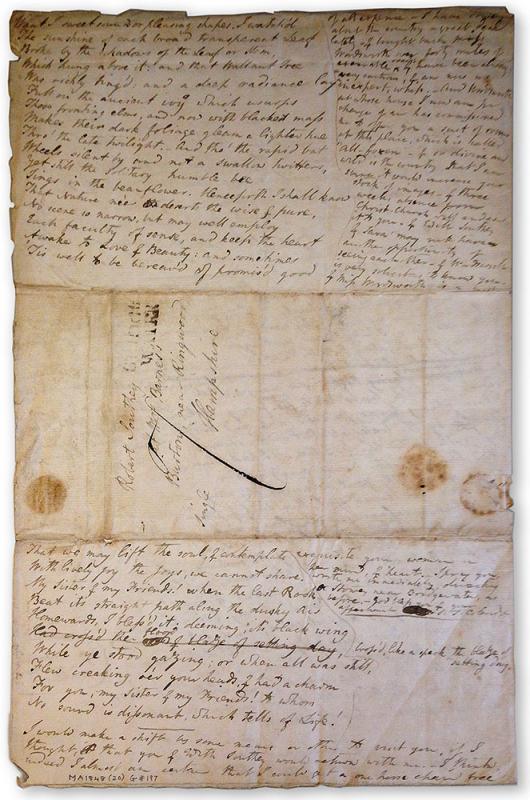

Just a few days after he composed the poem, Coleridge wrote it out in a letter to his close friend and brother-in-law Robert Southey, a letter that is now at the Morgan Library. This version of the poem differs significantly from the text that Coleridge later published; he expanded the description of the walk and made numerous changes in wording. The poem as it appears here, with lines crossed out and references explained in the margin, is both a personalized version and a draft in process. It is also the earliest surviving manuscript of the poem in Coleridge’s hand.

However, both this iteration and the later published poem end the same way: with a vision of a rook that flies “creeking” overhead, a sound that has “a charm / For thee, my gentle-hearted Charles, to whom / No sound is dissonant which tells of Life.”

At 7 in the evening these days, in New York and around the world, the sound of spoons banging on pans, of clapping, whistling, and whooping, is just such a sound.

Here is the full text of the poem on the Poetry Foundation’s website.

Sal Robinson

Assistant Curator

The Morgan Library & Museum