This is a guest post by Alexis Rodda, a classically-trained soprano and a Five-Year Fellowship recipient and doctoral candidate at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

The Ballets Russes was a ballet company that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe, but particularly in Paris. The company was innovative in its collaborations with contemporary composers and its daring, often sensual performances. The more I immersed myself in this world through a CUNY Graduate Center/Morgan fellowship, the more I became fascinated not only with the artistic aspects of the Ballet Russes, but also with the interpersonal relationships rife with love, passion, betrayal, and drama, all against the backdrop of Europe both before and after World War I.

The Ballets Russes was conceived by Sergei Diaghilev, born to a wealthy family in Russia in 1872. Though he originally had great dreams of being a composer, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, the preeminent Russian composer of the time, told Diaghilev that he had no talent for music, and Diaghilev bitterly gave up the pursuit.

His artistic aspirations did not end there, however; while at university, he formed a circle of art-loving friends, with whom he later founded the journal Mir iskusstva (World of Art). He became known for his artistic sensibilities and gained a prominent role at the Imperial Theater. However, Diaghilev’s opinionated nature and tendency to require dominance in his working relationships led to his dismissal.

Undeterred, he organized a huge exhibition of Russian portrait art in 1905, and in 1906 moved the exhibition to Paris, the city that would feature so prominently in his future artistic work. After a successful organization of a series of concerts of Russian music and a production of the opera Boris Gudonov at the Paris Opera, he was invited back to produce both opera and ballet, and thus the Ballets Russes company was created.

Diaghilev’s stated goal was to share with the world the magnificence of Russian art. He used Russian ballet dancers who could work for him when they did not have duties to the Imperial Theater. The productions were prized by Paris audiences for their sumptuousness, eroticism, and exoticism. Diaghilev also strove to be artistically innovative, seeking collaborations with contemporary composers whose music did not fit the traditional mold of ballet music. He created original works with Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel, among many others. One of his most notable collaborations was with Igor Stravinsky. The Rite of Spring, one of Stravinsky’s most famous works, emerged from his collaboration with Diaghilev.

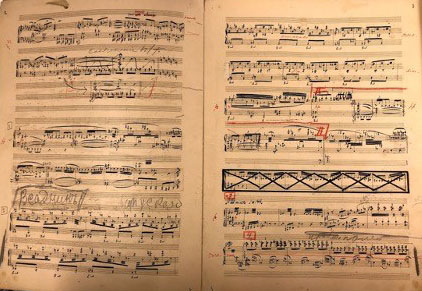

Figure 1. The autograph manuscript of the piano score of The Firebird by Igor Stravinsky, 1918. In the Robert Owen Lehman Collection.

One of the manuscripts I had the opportunity to view while on fellowship with the Morgan Library & Museum was that of Firebird, one of the musical works that resulted from the Stravinsky/Diaghilev collaboration. The piano-score manuscript is held at the Morgan on deposit in the Robert Owen Lehman collection. Looking at an original autograph manuscript of a musical score can provide incredibly valuable insight into the process of composition but also the process of mounting a performing arts production, even if that production took place 100 years ago. The most exciting thing to spot on an autograph manuscript are scribbles, erasure marks, and cross-outs. It’s fascinating to mull over why the composer chose to change something, especially if the change is minor, or if it’s a change of a musical meter from one to another just slightly different. What made the composer decide to make just one bar in 6/4 if it would have just as easily fit into three bars of two? What’s the motivation for reducing a florid melodic line in the violins to a simpler one? Why are huge swaths of musical material suddenly crossed out? Why did the composer decide to break a musical chord upwards instead of downwards? These are all things to consider when looking at the autograph manuscript of a musical score. When I look at a score such as Firebird, I imagine all the frantic scribbling and revisions as the result of Stravinsky hearing his score in real time at dance rehearsals, or sudden cuts as the result of something not working with the ballet’s stage concept.

Another reason why I think this work on the Ballets Russes became so absorbing is that each member of this highly artistically refined circle had a personality large enough to leap off the pages of biographies and historical accounts. Their artistic contributions did not serve as a background for the Ballets Russes but, rather, co-existed with the music and dance in the service of creating a greater artistic work. They truly exemplifiedd the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total art work,” the idea that a work of art can transcend the different regions of art, such as music, visual art, dance, opera, etc.

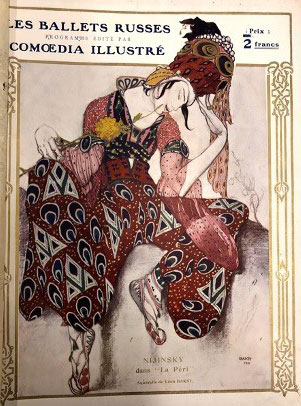

Figure 2. Image of Nijinsky in his costume from La Péri by Bakst, from a program for a performance of the Ballet Russes in 1911. From the James Fuld Collection.

For example, Leon Bakst was a Russian painter and artist within Diaghilev’s artistic circle, and he created the lavish sets and daring costumes that made the Ballets Russes so exciting to Paris audiences. The stories of sparring between Diaghilev’s and Bakst juxtaposed with the creative electricity between them painted a picture of a passionate but turbulent working relationship.

Another fascinating character of the Ballet Russes is Ida Rubinstein. Rubinstein was born to Russian Jewish parents in 1883 and became an enormously rich heiress in 1892 after the death of her father. She was given an excellent artistic education, and though she was not a dancer in the way the other members of the Ballet Russes were, she had become a master of the art of miming and thrilled audiences with her beauty, stage presence, and mysterious aura.

She moved to Paris to pursue acting and was cast as part of the Ballet Russes in Cléopâtre in 1909. Rubinstein was immediately a sensation with audiences, but she found that dancing with Diaghilev’s company meant she was often too tired after long and strenuous rehearsals to focus on her own artistic pursuits. She decided to separate from Diaghilev’s company and break out on her own. Her relations with Diaghilev became increasingly strained when it became clear that she was not simply a rich dilettante but was capable of creating extraordinary artistic collaborations that resulted in impressive commissions. Rubinstein also hired the same artists Diaghilev did, but could pay them well beyond what Diaghilev could ever afford.

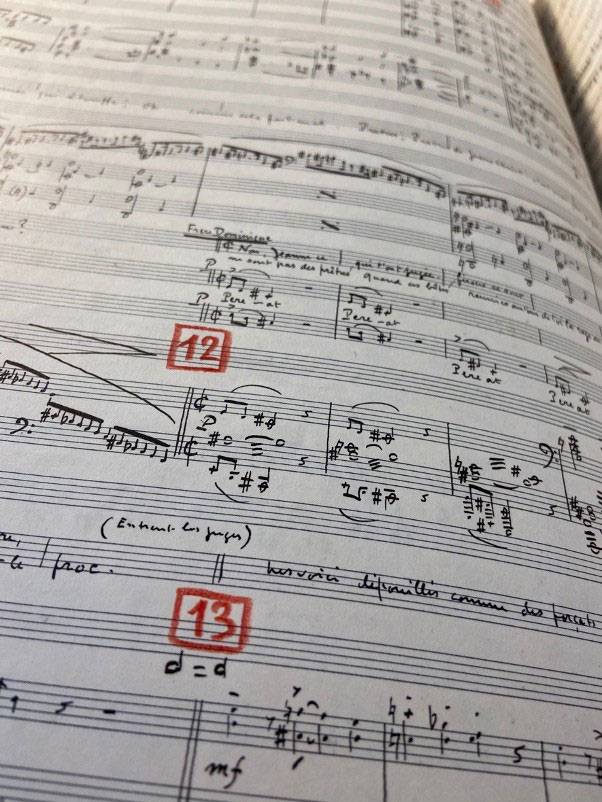

Figure 3. Autograph manuscript of Jeanne d'Arc au bûcher by Arthur Honegger, 1935. From the Robert Owen Lehman collection.

In Rubinstein’s artistic maturity, she began to commission works of art that could not be clearly defined as opera or ballet, as they often combined spoken word, singing, dancing, miming, and the artistry of the same circle of creators valued by Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes. Rubinstein and her works fascinate me because her role as patroness, artist, and impresario went against the archetypal role of women at the time, much to the dismay of her family. However, Rubinstein found a way to create art on her own terms. One such example is Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher, pictured above. Honegger called his work a “dramatic oratorio,” but the work is a combination of spoken drama, opera, and oratorio. Rubinstein took on the title role in her capacities as a dramatic actress, but the work also included a chorus, orchestra, and vocal soloists.

My time at the Morgan was much different from what I imagined when I first applied for this fellowship. At the time of my interview, the United States was just beginning to discuss the COVID-19 outbreak. I was only briefly in New York, on a break from my Fulbright year, and right after interviewing at the Morgan, I flew back to Austria. Only a few weeks later, my program was cancelled and I was on a plane back to the USA.

Exploring the materials during the autumn months, even though it was from my own home instead of at the Morgan, gave me purpose and structure in what might have otherwise been formless time. I was able to escape into a world where performance was still a possibility, and in-person collaboration was constant. My time with these beautiful materials and my relationships with the characters of the Ballets Russes were invaluable to me this past autumn.

Alexis Rodda is a classically-trained soprano described by New York Classical Review as having “a lovely voice, full of color and body in every register.” She attended Princeton University (BA), Mannes College (MM), and currently attends CUNY Graduate Center as a Five-Year Fellowship recipient and doctoral candidate. In March 2019, she was chosen as a Fulbright Scholar to travel to Vienna and conduct research in the exil.arte Zentrum (The Exiled Art Center). She has won several grants for her research, including the Elebash Grant (2016 and 2018) and a CARA grant from the PublicsLab at CUNY.

Alexis Rodda is a classically-trained soprano described by New York Classical Review as having “a lovely voice, full of color and body in every register.” She attended Princeton University (BA), Mannes College (MM), and currently attends CUNY Graduate Center as a Five-Year Fellowship recipient and doctoral candidate. In March 2019, she was chosen as a Fulbright Scholar to travel to Vienna and conduct research in the exil.arte Zentrum (The Exiled Art Center). She has won several grants for her research, including the Elebash Grant (2016 and 2018) and a CARA grant from the PublicsLab at CUNY.

As an active classical music performer, Alexis has performed in many operatic roles including Miss Jessel (Turn of the Screw), Agathe (Der Freischuetz), Second Lady (Die Zauberflöte), Hanna (The Merry Widow), Rosalinde (Die Fledermaus), Nedda (I Pagliacci), Nora/Alice (She, After), The Witch (Hansel und Gretel), Berta (Il Barbiere di Siviglia), Mimi (La Boheme), Genovieffa (Suor Angelica), and Penelope (Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria).

At Princeton, she was a Lewis Center for the Arts grant winner chosen to create and sing a new opera by composer Maxwell Mamon, Rosaleen, which had its premiere in Richardson Auditorium. She was a 2013 Boston Metropolitan Opera National Council District Winner and Regional Finalist and a 2014 NYC Metropolitan Opera National Council Encouragement Award Winner. She was a 2016 Serge & Olga Koussevitsky Young Artist Award Finalist and a 2016 Violetta DuPont Competition Encouragement Award Winner.

Additionally, she is a professional singer at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City and currently serves as Director of Music at Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Ozone Park, Queens.