This post was created by Lindsey Tyne, Associate Paper Conservator

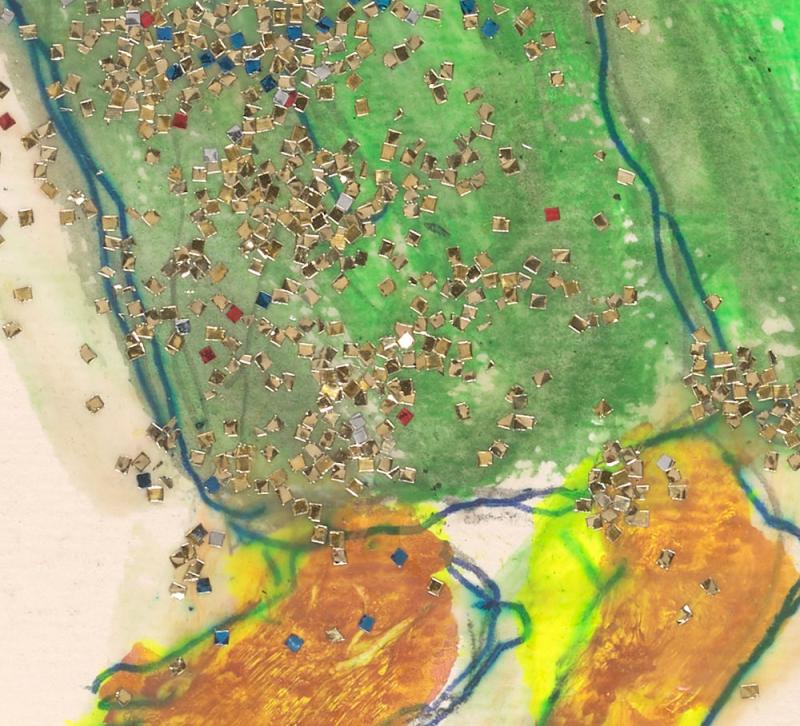

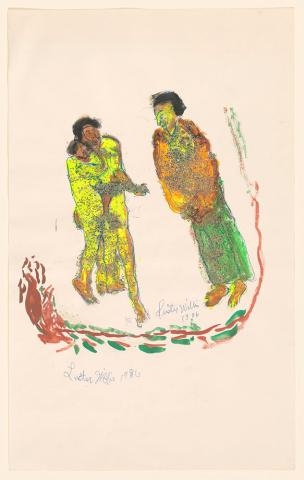

The gold, silver, red, and blue flakes that give Standing Together, 1986 (2018.105) by Luster Willis (1913–1990) its seductive sparkle are commonly known as glitter. Many of us instinctively know what glitter looks like and may even recall a childhood craft project or a greeting card we recently received, despite the fact that how glitter is made and what it is made of are trade secrets. Beyond art, craft, and decorative objects, glitter is all around us, incorporated into everyday products such as cosmetics, writing inks, industrial paints, clothing, and even edible glitter for decorating cakes and cookies.

Much of the non-edible glitter in the United States leads to the state of New Jersey where it is manufactured by Meadowbrook Inventions, founded in 1934, in Bernardsville and Glitterex, founded in 1963, in Cranford. Both companies list a dizzying array of glitter products. Some of the tiniest flakes, averaging 0.002 inch (0.0508 mm) wide, are found in cosmetics where we see the reflected light, but not necessarily the individual flakes.

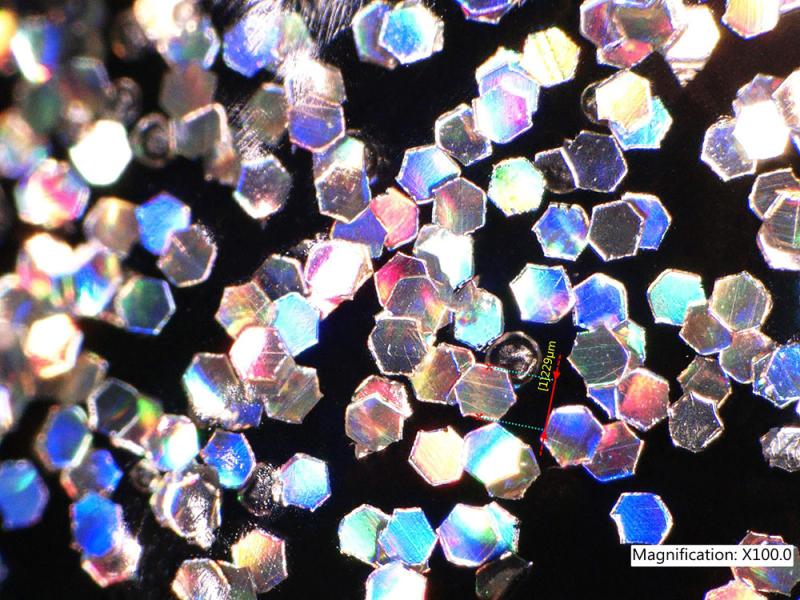

A flake 100 times larger than cosmetic glitter, up to 0.25 inch (6.35 mm) wide, is still considered glitter. At this large size, its shape, color, and surface reflections are easily observable with the naked eye. Hexagons and squares are common shapes for glitter, but not the only shapes manufactured. Meadowbrook and Glitterex list hearts, diamonds, and stars as some of their speciality shapes.

Luster Willis, American, 1913–1990, Standing Together, 1986. Tempera, glitter, glue, blue ballpoint pen, and graphite. Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund, 2018.105. © 2021 Estate of Luster Willis / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Janny Chiu.

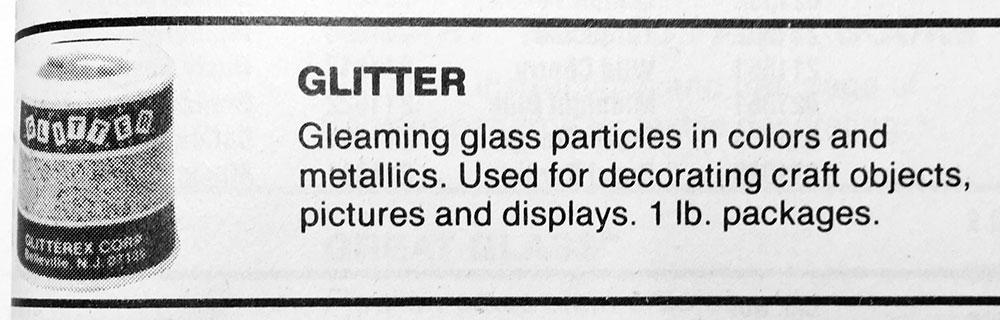

The metallic reflection, color, square-shape, and size of the glitter in Standing Together is most similar to craft glitter, a type of glitter easily available in the 1980s. In the 1984 NY Central Art Supply Company Catalog, craft glitter from Glitterex is listed with the caption "Gleaming glass particles in colors and metallics. Used for decorating craft objects, pictures and displays." The producers of this catalog took some liberties in their description, because this glitter was not made of glass, but most likely aluminum-coated plastic, as confirmed by recent correspondence with Jeet Shetty, the Vice President of Operations at Glitterex.

Even though the manufacturing specifics are trade secrets, we can glean some steps of the process from published sources. Non-edible glitter starts as a multi-layer film, with the first layer of most types being a clear plastic; polyvinyl chloride (PVC) for craft glitter and polyester (polyethylene terephthalate; PET) for glitters that need more chemical stability. If the final glitter is to appear metallic, the clear plastic is coated with aluminum through vacuum metallization. This is a process where solid aluminum is vaporized in a vacuum chamber under high-heat conditions and then deposited as a thin, even layer on both sides of the plastic to create a shiny metallic silver film. If the final glitter is to be translucent and not metallic, the aluminizing step is skipped. If the final glitter needs to withstand high temperatures, the first layer of the film will not be plastic but solid aluminum. Next, colored and colorless plastic layers, as well as textures, are applied to the film in varying thicknesses to impart the desired optical qualities and surface protection. After all the properties of the final glitter are added to the film, it is cut into flakes. The machine that cuts the flakes is simply known as a glitter cutter, which uses rotary-die-cutting techniques to produce flakes of a specific size and shape. Craft glitter is the least technically advanced and also the thickest glitter manufactured with this process. It has approximately three to five layers averaging 0.006–0.007 inch (0.1524–0.1778 mm) thick, while a piece of cosmetic glitter with potentially more layers could be as thin as 0.0005 inch (0.0127 mm). Note the noncorrelation between the number of layers and final thickness of a glitter flake.

The manufacture of glitter film and the method of its cutting are so idiosyncratic that the final flakes are highly individualistic. So much so that forensic chemist and now retired criminologist Robert D. Blackledge stated at the 2007 Trace Evidence Symposium that glitter is the “most nearly perfect contact trace.” Both the chemical and visual properties of a glitter flake can provide information that leads back to a specific manufacturer and can be used to match one flake to another. The visual differences between glitter flakes are revealed with magnification. For example, when this tiny nail-polish glitter measuring 0.009 inch (0.2286 mm) across is magnified 100 times, the irregularity of the hexagon-shape and inconsistency between flakes is evident. These microscopic features are specific to the glitter cutter.

For all the advanced technology required to manufacture glitter, Willis used his glitter in an untechnical manner. In Standing Together, he applied a layer of clear adhesive and simply sprinkled his glitter over the surface while it was still wet. The flakes were frozen into place when the adhesive dried, leaving the surface of the glitter uncovered to do what it does best, sparkle. A sparkle that will last many years due to the relatively good stability of the plastic and metal layers that make up the flakes in combination with the adhesive. Another concern would be the potential for the glitter to fall off over time. The likelihood of the glitter on this drawing spontaneously falling off in large quantities is low, as the flakes are particularly well adhered. Still, losing a flake here and there is not unexpected and certainly in keeping with glitter’s reputation for getting everywhere.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blackledge, Robert D. “Glitter as Forensic Evidence” presented at Trace Evidence Symposium sponsored by the NIJ and the FBI, Clearwater Beach, Florida, 2007.

Blackledge, Robert D., Kurt Gaenzle, and Edwin L. Jones, Jr. “Holographic Glitter” Modern Microscopy, The McCrone Group, 2010. Accessed October 1, 2021.

Weaver, Caity. “What Is Glitter? A strange journey to the glitter factory.” New York Times, December 21, 2018.

Lindsey Tyne

Associate Paper Conservator

The Morgan Library & Museum

Standing Together, 1986 by Luster Willis (1913–1990) is currently on view in the exhibition Another Tradition: Drawings by Black Artists from the American South, September 24, 2021, through January 16, 2022.