I came to the Morgan Library & Museum in search of Eleanor Franklin Egan, a forgotten writer of the First World War. While preparing my book manuscript for the First World War, Anticolonialism and British India, 1914–1924 (Routledge, forthcoming), I saw a reference to writings by Eleanor Franklin Egan (1879–1925). Egan fit into my book project’s theme because in November 1917 she traveled to the war zone of Ottoman Mesopotamia to report on the British war effort there. Taking the Pacific route, she sailed to Bombay via Singapore and then went to Basra and Baghdad before returning to the United States via India. Her articles on that remote but critical frontline (the Great War was a global war, remember) were published in the illustrated magazine Saturday Evening Post. Egan’s book The War in the Cradle of the World was a huge success and for a brief period made her a very well-known writer. Thinking that Eleanor Egan’s descriptions of wartime India and Baghdad would make an interesting section in my book as an American perspective on the British Empire at war, I decided to track her papers down.

What remains of Eleanor Egan’s papers (including documents, articles, and some personal memorabilia) are cataloged in designated folders within the Martin Egan collection at the Morgan. Martin Egan (1872–1938), Eleanor’s husband, was a former Associated Press reporter and became the public relations director for J. P. Morgan & Co., working closely but in a low-key manner with many prominent people including John (“Jack”) Pierpont Morgan, Jr. himself.

My work at the Morgan made me aware of Eleanor Egan’s complex character and her contradictory positions. Underneath the breezy authorial style she adopted for her readers was a difficult story of struggle and endeavor. Eleanor was a working woman who traveled the world in search of stories but who was also against the women’s suffrage movement (she later changed her mind and admitted she had been wrong). Egan was an Anglophile supporter of the British Empire with all its racial hierarchy who also supported famine victims in Russia and China. She was a survivor during a time of global conflict, and quite literally too—her ship was torpedoed by a Turkish or Austrian submarine in the Mediterranean Sea in 1915. To read her account of this experience—one typewritten for publishing, the other a letter to Martin Egan in which her charged emotions are reflected in the indecipherable scrawl of her writing—is to come closer to understanding the madness of those times. After the war ended, Eleanor continued to chase stories across the globe, reporting on the Russian famine during that country’s civil war (1917–22), the famine in China during the time of the warlords, and the Philippines, where she strongly supported American rule.

President Warren G. Harding (1921–23) appointed Eleanor Egan a member of the advisory council at the 1922 Washington Disarmament Conference (also called the Naval Conference). Egan had a ringside view of important developments during the First World War and the postwar period. She returned to India in 1923 and reported on the upheaval and changed mood of the country after the Gandhian agitation of Non-Cooperation (1920–1922). Would Eleanor Egan have changed her mind about the British Empire’s role as a force for good in the world? She carried with her Mark Twain’s book More Tramps Abroad for guidance and insight into India; Twain was a well-known anti-imperialist in his time. We will never know the full arc of Egan’s intellectual trajectory, for she fell ill soon after returning to New York and died in January 1925. I find that Egan’s place in my book has expanded beyond the section I had in mind. I now situate her life and career in a chapter on the communications and information networks connecting the British Empire and the United States during and after the Great War.

I also came to know Martin Egan better. In an era where women had few opportunities for professional work outside the house, Eleanor found crucial support in Martin. It was Martin who often reached out through his network of journalistic and banking contacts to find Eleanor useful introductions in different parts of the world. This also reflects the global financial reach of the company Martin worked for, J. P. Morgan & Co.

It was a pleasure uncovering Egan’s writings in the quiet, well-lit Reading Room of the Morgan where patrons come from different parts of the world. Here I was, trying to decipher the sprawling handwriting of a busy journalist reporting the Great War from Turkey while at a table across from me sat a scholar poring over the beautiful jewel-like illustrations of a medieval manuscript. During my breaks, I lingered over the fabulous collections and exhibitions in the Morgan Library & Museum, indulging my senses with the porcelains, the paintings, and the Thomas Gainsborough exhibition.

Authors can do no work without librarians and archivists, colleagues whose labor is indispensable to the process of intellectual and artistic production. Not only is the setting of the Morgan Library & Museum beautiful but the archivists are a bunch of friendly professionals who helped me find the material I needed. Sylvie Merian loaned me material from her personal library so I could continue to explore the Armenian Genocide that Eleanor Egan reported on during her war travels. Sylvie also helped me track additional Eleanor Egan papers in the Morgan’s collection. Christine Nelson expressed a warm interest in my research of Eleanor Franklin Egan and her forgotten writings from the era of the First World War. Maria Isabel Molestina is an effective Head of Reader Services who runs a tight ship in the Reading Room and with whom I chatted during breaks. It was also a pleasure to interact with Emma Davidson and Polly Cancro. Thanks to the team at the Morgan for all their help and their conviviality.

It is a great pity that Martin Egan’s second wife, Nell, may have destroyed papers relating to both Eleanor and Martin before the collection came to the Morgan. Eleanor Egan’s life is a remarkable window on global war and on American women’s activities in the early twentieth century as they pursued professional and personal opportunities in different parts of the world. I am grateful to the Morgan for the opportunity to research Eleanor Egan’s life and to present her story to a scholarly audience.

Sharmishtha Roy Chowdhury is a writer and historian, specializing in modern world history and modern European history. She has taught history at Northwestern University, the University of Connecticut and Emerson College, Boston. Her historical novel The Communist Cookbook was published by Penguin in 2013. Her scholarly book The First World War, Anticolonialism and Imperial Authority in British India, 1914–1924 is being published by Routledge in 2019.She is currently working on another historical novel set during the 1947 Partition of India.

Sharmishtha Roy Chowdhury is a writer and historian, specializing in modern world history and modern European history. She has taught history at Northwestern University, the University of Connecticut and Emerson College, Boston. Her historical novel The Communist Cookbook was published by Penguin in 2013. Her scholarly book The First World War, Anticolonialism and Imperial Authority in British India, 1914–1924 is being published by Routledge in 2019.She is currently working on another historical novel set during the 1947 Partition of India.

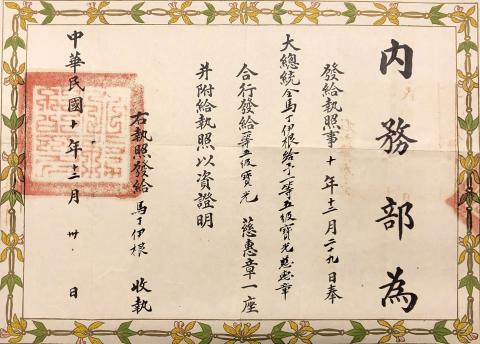

![A brownish paper document with black printed text. The translation of the certificate from the Ministry of Interior reads: This is to certify that by order of Presidential Mandate issued on the 29th day of the 12th moo[n] of the 10th year of the Republic of China, Mrs. Martin Egan is hereby conferred Pao Kwang Sze Huei Chang, First Class, Fifth Grade, (Brilliant Order of Kindness and Benevolence). December 30th 1921. There is a black rectangular stamp on the bottom right that reads Seal of Ministry of Interior.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/blog/translation.jpg?itok=61YmzwMb)