Ivanhoe (detail from binding)

Sir Walter Scott, arguably the most successful writer of his day, was the first English-language novelist to be represented by a literary agent. In the last twenty years of his life, he published 23 works of fiction -- all anonymously -- and James Ballantyne, who was also Scott's business partner, printer, and former schoolfellow, acted as a liaison and literary agent to help to obscure Scott's identity.

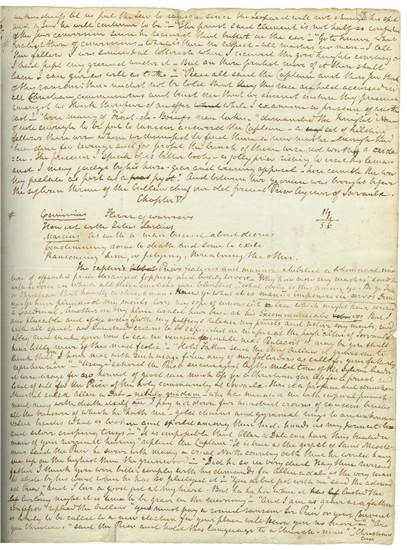

This is a page from Scott's original draft of Ivanhoe(1819). Examine his confident, fluid (albeit quite small) handwriting. There are few corrections on this page, which is typical of the rest of the manuscript. He wrote on the rectos of the pages only, leaving the versos available for later corrections and rewrites, but as you flip through the manuscript many of the versos are blank, and it is so clean that it almost looks like a fair copy (a corrected, revised draft). It was at this initial stage of composition that his fiction fades behind the curtain of anonymity -- as Scott completed sections of his novels, Ballantyne re-copied them in their entirety before he sent them to the printing house. This ensured that Scott's handwriting would not be recognized by the compositors, and the publishers did not have contact with the author.

This is a page from Scott's original draft of Ivanhoe(1819). Examine his confident, fluid (albeit quite small) handwriting. There are few corrections on this page, which is typical of the rest of the manuscript. He wrote on the rectos of the pages only, leaving the versos available for later corrections and rewrites, but as you flip through the manuscript many of the versos are blank, and it is so clean that it almost looks like a fair copy (a corrected, revised draft). It was at this initial stage of composition that his fiction fades behind the curtain of anonymity -- as Scott completed sections of his novels, Ballantyne re-copied them in their entirety before he sent them to the printing house. This ensured that Scott's handwriting would not be recognized by the compositors, and the publishers did not have contact with the author.

Scott published critical and historical works under his own name, and he owned his poetry, which brought him fame and critical recognition in its own right (he declined the poet laureateship in 1813), so it isn't as if he had general anxieties about putting his name on a title page. But why did he insist on -- and take great steps to protect -- his anonymity when it came to works of fiction?

And his anonymity was complete. Recently, I read Scott's letters to the Marchioness of Abercorn. Their correspondence began in 1806 (with a letter, incidentally, that contains the earliest surviving reference to his work on The Lady of the Lake), and for a number of years they wrote each other frequently. Scott's letters, while written with a clear sense of deference owed to a social superior, are lengthy and very personal. His topics of conversation range from analyses of contemporary politics to detailed discussions of his family, home life, and writings. He sent her early proofs of his poems, asking for her and her husband's critical responses, so it seems that he trusted her literary acumen, and he sent her his novels as they were published too. But even when she has pointedly asks if he knows who the author is, he dances around the topic and pretends to have gossip, but no real knowledge, about the author. In 1815, he throws her off the scent by promising to tell her what he knows about the author of Waverly when he sees her next in London.

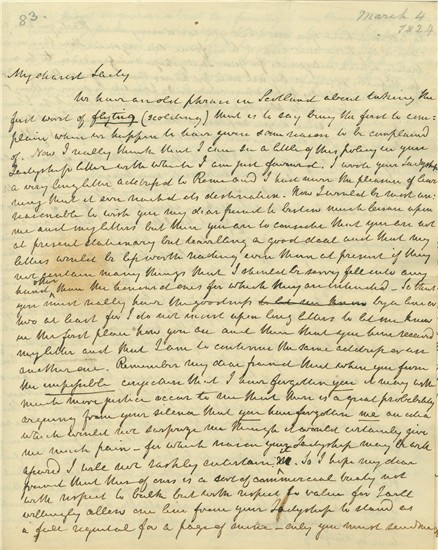

By the time of this 1824 letter (shown above), Scott has been corresponding with the Marchioness for nearly twenty years and maintaining his literary anonymity for a decade. But although he was reluctant to be identified, he was just as reluctant to have false rumors swirling about. Here, he responds to gossip that has arisen as a result of the public "so erroneously" identifying him as the author of his novels with such forceful statements that although he does not straightforwardly report that he is in fact not the author of "those novels" it would be difficult to not infer that -- and I think that Scott probably hoped she would then spread that rumor of his forceful denial.

Scott was being identified as the author of Waverly mere months after its initial publication in 1814, but he only finally came out from behind his anonymous mask in 1827. During this period, it was far from unusual to publish novels anonymously, but (as David Hewitt points out) his reasons -- he called it an experiment, cited the impropriety of novel-writing for someone in his position (in addition to his literary pursuits, was also a clerk to the Court of Session for the Scottish supreme court), and alleged that Lord Byron had surpassed him in popularity -- don't quite seem to be reason enough in themselves. In theDictionary of National Biography, Hewitt goes on to propose some additional reasons: that Scott "had been gradually overcrowded with social admirers, he liked being mysterious, it was a good sales gimmick." All of these reasons make sense too, but still don't fully illuminate Scott's ability to maintain that facade even with close correspondents.

For more information about the Ivanhoe manuscript, click here; for more about his correspondence with the Marchioness of Abercorn, click here.

The Leon Levy Foundation is generously underwriting a major project to upgrade catalog records for the Morgan's collection of literary and historical manuscripts. The project is the most substantive effort to date to improve primary research information on a portion of this large and highly important collection.