This is a guest post by Timothy Gress, currently an undergraduate at Manhattan College.

I first came to the Morgan Library & Museum to view the exhibition I’m Nobody! Who are you? The Life and Poetry of Emily Dickinson in 2017. During my initial visit I was struck not only by this carefully curated exhibition, but also by works on display in J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library—especially a first edition of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Little did I know that I would soon have the opportunity to write exhibition labels for these same exhibit cases as part of the Morgan’s Treasures from the Vault series.

My next interaction with the Morgan came a year later when I reached out to the Printed Books & Bindings Department to inquire about the possibility of an internship that would fulfill the requirements of an English literature elective. Having already had experience working with my school’s collection of rare eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century novels formed by prominent New York collector DeCoursey Fales—who also founded the Fales Library at New York University—I was contacted a week later by John McQuillen, associate curator of Printed Books & Bindings, to see if I would be interested in working to inventory the Morgan’s collection of extra-illustrated books.

Extra-illustration, as I soon came to learn, took hold in the late eighteenth century when Richard Bull, a politician and art collector, shocked the collecting world by adding a finely curated collection of more than 12,500 prints to James Granger’s Biographical History of England (1769) in an attempt to radically redefine how we experience biography. What collectors, librarians, curators, and scholars now refer to as the process of extra-illustration, or grangerizing, includes not only the addition of prints, but also of engravings, etchings, watercolors, manuscripts, receipts, and even pages taken from other books, to particular volumes.

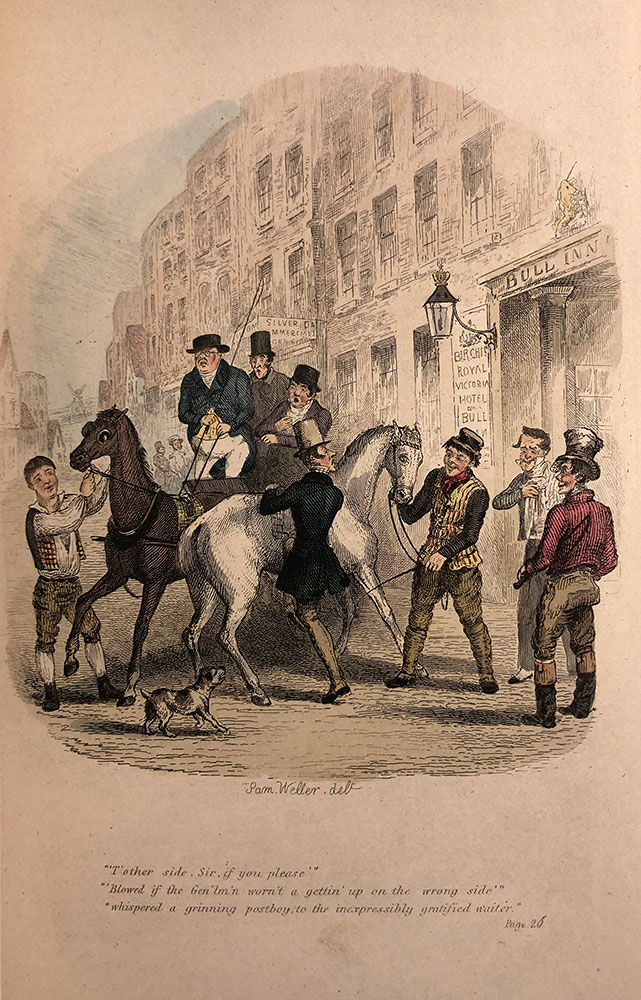

Illustration of Mr. Pickwick. Part of a suite of Pickwick plates done by Thomas Onwhyn under the pseudonym “Sam Weller” (London: E. Grattan, 1837). PML 6666, inserted facing page 69.

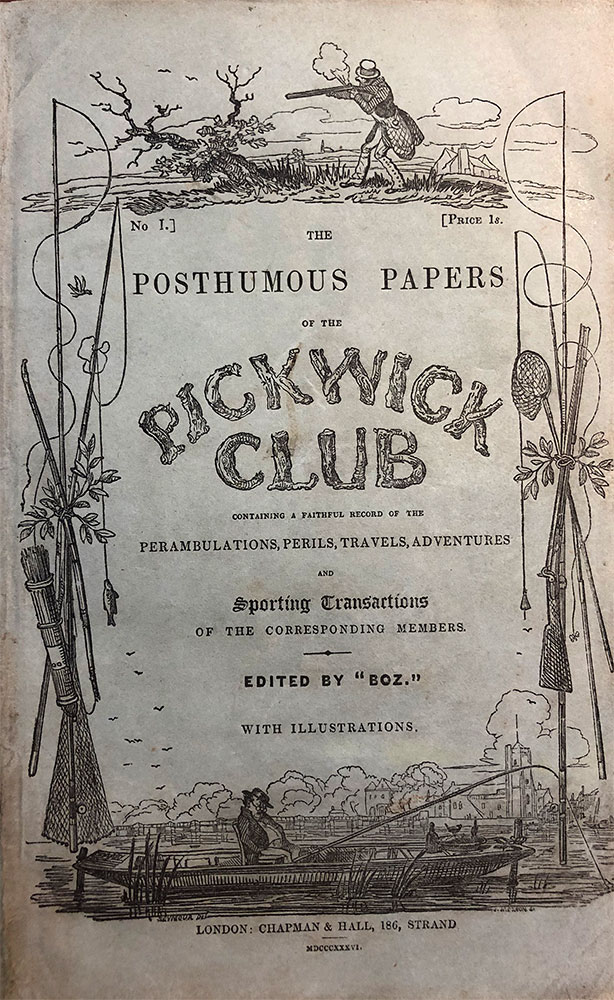

Front cover of the first edition of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick featuring original illustrations by Robert Seymour (London: Chapman & Hall, 1836). PML 131814.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, the craze for extra-illustration was popularized among wealthy American collectors. After visiting Morgan’s collection of extra-illustrated books, Daniel Tredwell, author of A Monograph on Privately-Illustrated Books: A Plea for Bibliomania (1882), exclaimed that, “Mr. Morgan has gone further, and has extended the realm of the private illustrator to an extent with a liberality which none but a true and genuine booklover would ever dream of” (369).

The most intriguing extra-illustrated work that I inventoried was the 1887 Victoria Edition of Charles Dickens’ The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (PML 6666). When Pickwick was originally published in 1837, new advances in the technology of printing had allowed for the cheap and easy production of engravings, etchings, lithographs, and other print mediums. The newfound accessibility of these materials, along with the fantastic popularity of the novel, led to the release of several suites of additional plates that were meant to be inserted, along with the original illustrations etched by H. K. Browne and others, into copies of Pickwick.

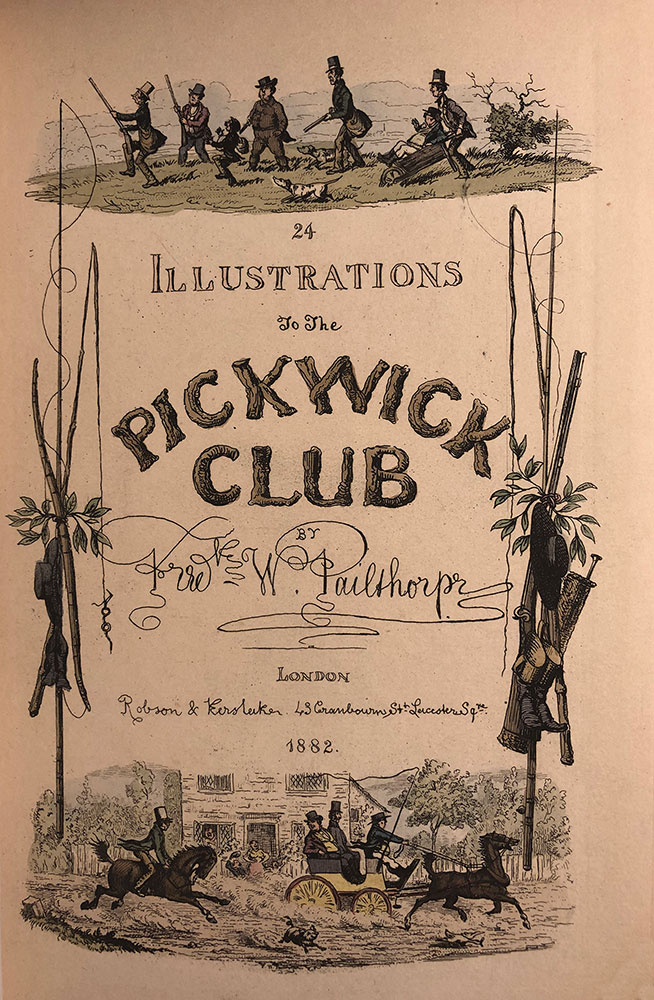

In 1891, for the outstanding price of £40—when only a few years earlier a copy of Nicholas Nickleby bound in full morocco cost £1, 6 shillings—the English bookseller Henry Sotheran, using his surplus stock of these extra-illustrations, was able to produce for Morgan a unique, four-volume set of one of Dickens’s most celebrated works. Paired with the suite of photogravure plates that were original to this edition were two sets of lithographs done by Alfred Crowquill, four additional sets of etchings done by F. W. Pailthorpe and Thomas Onwyn, one set of proof wood engravings from the 1873 household edition of Pickwick, one proof set of the original etchings on India paper, along with a set of etchings stripped from a set of the original twenty monthly parts. Containing at least four versions of each plate, Morgan’s Pickwick attempts to provide a complete picture of the people, places, and events in the novel. Therefore, this copy of Pickwick, and the rest of the Morgan’s vast and varied collection of extra-illustrated books, taught me not only about print culture in the nineteenth century–something that I will be returning to as an avenue of future study–but also Morgan’s methods of collecting before he hired Belle da Costa Greene as his librarian in 1905.

However, the scope of my internship at the Morgan expanded well beyond inventorying extra-illustrated books. Being able to experience the full range of tasks under the purview of the Printed Books & Bindings Department allowed me, as someone who is interested in pursuing a career in the field of rare books, gain a clearer understanding of the day-to-day duties of a curator. After learning from curators John McQuillen and Sheelagh Bevan proper methods for accurately cataloging and researching individual works in the collection, planning exhibitions, and viewing prospective acquisitions at auction (to name only a few duties), I have come to realize the vitally important role that libraries and museums play in making available, both to researchers and to the general public, distinguished and culturally significant collections. I am extremely grateful to the Morgan’s staff both for affording me the opportunity to work closely with them on important projects and for encouraging me to continue working toward a career in curatorship. I look forward to continuing to use the Morgan’s extraordinary collections as a researcher.

Timothy Gress is currently an undergraduate at Manhattan College interested in the study of Romantic and Victorian literature and print culture and in early twentieth-century American book collectors. He became interested in rare books three years ago when, as a student worker, he discovered his school’s little-known collection of rare eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century novels formed by DeCoursey Fales. In the fall of 2019 he will begin graduate studies in the dual MA/MLS at New York University and the Palmer School of Library and Information Science at Long Island University.

Timothy Gress is currently an undergraduate at Manhattan College interested in the study of Romantic and Victorian literature and print culture and in early twentieth-century American book collectors. He became interested in rare books three years ago when, as a student worker, he discovered his school’s little-known collection of rare eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century novels formed by DeCoursey Fales. In the fall of 2019 he will begin graduate studies in the dual MA/MLS at New York University and the Palmer School of Library and Information Science at Long Island University.