Dear Diary, Dear Beloved: Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891). Forbidden to correspond with Charles Kingsley, the man she adored, Fanny Grenfell kept a diary in the form of unsent love letters instead.

Dear Diary, Dear Beloved: Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891). Forbidden to correspond with Charles Kingsley, the man she adored, Fanny Grenfell kept a diary in the form of unsent love letters instead.

About the Diary

Twenty-five-year-old Fanny Grenfell was drawn to the emerging Catholic revival movement in England and looked forward to a life of chastity. Cambridge undergraduate Charles Kingsley, son of an Anglican clergyman, was having serious doubts about his own faith. All that changed dramatically when the two met in 1839. Their passion for each other was strong and immediate. Fanny guided Charles into a firm embrace of Christian doctrine, and Charles convinced Fanny that sex—within the confines of marriage—was a sacred blessing.

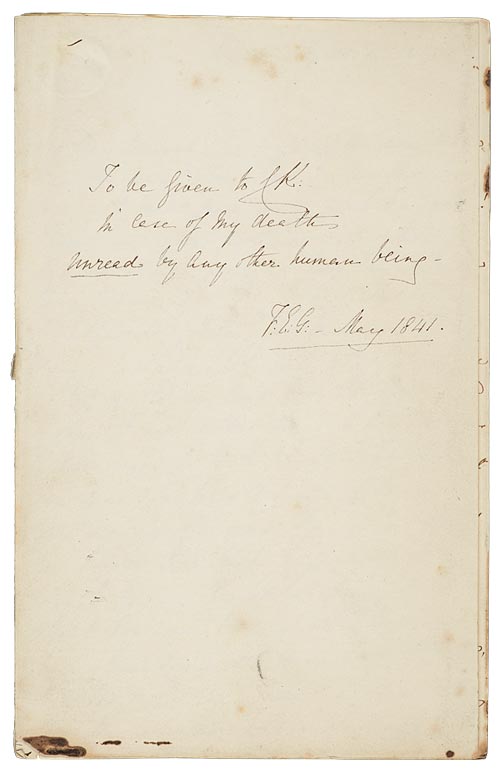

The match was unacceptable to Fanny's family, and they sent her on a European tour to keep the two apart. Charles was poor and Fanny rich, and, to make matters worse, he was five years her junior. Forbidden to commit herself formally to Charles, Fanny did so surreptitiously: She began a journal in 1841, carrying it with her as she traveled, framing each entry as an intimate letter. She told the absent Charles that "for months this may not meet your eye, perhaps never!" and explained the purpose of her exercise: "if I die, this Journal will be a melancholy satisfaction to you, & if we are engaged, it will still be a pleasure to you to see how my mind & heart were employed in the long blank." She penned a warning on the first sheet: "To be given to C.K. in case of my death, unread by any other human being."

The journal became Fanny's outlet for the exalted feelings—"the inexhaustible torrent of my love"—that she was unable to express directly to her beloved. Using over 600 exclamation points to punctuate her breathless declarations, she wrote of their tenuous plans for a reunion ("I have been vibrating between Hope & Fear"), the strength of their love, even in separation ("time & space seem conquered & vanish away!"), and, occasionally, of the strain she felt in defying her family ("no man can appreciate the sacrifice a woman makes in a case like this"). Desperate for word from Charles, she dreamed that she had received a letter, but, upon opening it, "found it was my own writing inside — the Journal I had kept for you."

The journal became Fanny's outlet for the exalted feelings—"the inexhaustible torrent of my love"—that she was unable to express directly to her beloved. Using over 600 exclamation points to punctuate her breathless declarations, she wrote of their tenuous plans for a reunion ("I have been vibrating between Hope & Fear"), the strength of their love, even in separation ("time & space seem conquered & vanish away!"), and, occasionally, of the strain she felt in defying her family ("no man can appreciate the sacrifice a woman makes in a case like this"). Desperate for word from Charles, she dreamed that she had received a letter, but, upon opening it, "found it was my own writing inside — the Journal I had kept for you."

After they finally met for four days in January 1842, Fanny declared that "in you I have found Father, Mother, Friend, Husband!" After the embraces they had shared, Fanny's nights without Charles were a particular agony: "I stretch out my arms to you — & find you not — & then I fold my hands, those hands which have been clasped convulsively by yours, across my bosom, where that beloved head has rested – & the lips which you have kissed utter useless moans — & then I writhe under the intolerable consciousness that you are not near me"

At the beginning of her diary Fanny wrote a few lines from Romeo and Juliet: "O think it thou, we shall ever meet again—I doubt it not; & all these woes shall serve / For sweet discourses in our time to come!" But her story had a much happier ending than Shakespeare's tale of star-crossed lovers. The determined lovers endured separation, overcame familial opposition, and finally consummated their secretive courtship. Fanny Grenfell and Charles Kingsley wed in 1844, had four children, and enjoyed a passionate marriage, reconciling spiritual and carnal bliss. Charles became a successful clergyman, social reformer, and author of the popular works Westward Ho! and The Water Babies.

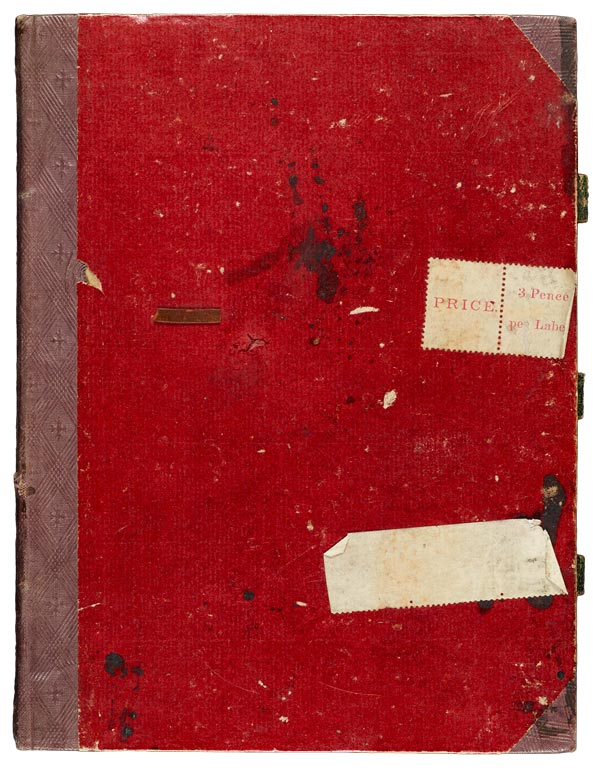

Diary of Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891), 1841–42. Gift of Sir John Pope-Hennessy in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Morgan, 1974.

Warning penned in the diary of Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891), 1841–42. Gift of Sir John Pope-Hennessy in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Morgan, 1974.