A French formal garden. Illustration in Poetry & Patronage: The Laubespine-Villeroy Library Rediscovered, a Morgan exhibition catalogue, published in 2020. Collection du musée du domaine départemental de Sceaux. Photo Pascal Lemaître

In 2010 the Morgan presented an exhibition on the cultural history of gardens in Europe and America, Romantic Gardens: Nature, Art, and Landscape Design, curated by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers and others. Copies of the catalogue are still available in the Morgan Shop. The catalogue touches briefly on a question still debated by garden historians: what are the origins of the English style of landscape design? Art critics in the Romantic period praised the asymmetrical layout of English estates, their winding paths, stately lawns, placid lakes, striking vistas, and picturesque groves of trees. They declared that style to be truer to nature than the rigid geometry in French formal gardens, an opposing view rife with political implications. One style expressed a love of liberty, the other the top-heavy framework of the ancien régime. Some aristocratic patrons opted for both, one plot next to the other, hedging their bets as it were but also trying to keep up with the times. In the following, I expand on a catalogue entry I wrote about a book that played a small but significant part in these stylistic developments.

Chinese gardens provided a precedent for this newfound naturalism. British writers mentioned them as early as 1685 and commended their pleasing irregularity and “artful Confusion.” The Chinese fashion became so popular that the architect William Chambers was moved to correct and codify it in Designs of Chinese Buildings (1757) and A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772). Chambers had visited China and claimed to speak from personal experience. Although his treatises were sometimes just as fanciful as the popularizations, they were very influential in England, France, and Germany. They helped him to secure royal patronage, which gave him the opportunity to build the famous pagoda in Kew Gardens. Pagodas were equally popular in France as well as other types of outdoor chinoiseries, the origins of which were explicitly acknowledged in the term jardin anglo-chinois. What is now Parc Monceau in Paris began as a 46-acre folly designed for Philippe d’Orléans, duke of Chartres, by Louis de Carmontelle, an eclectic artist obviously influenced by Chambers.

The lines of influence from East to West are hard to trace. Books and prints about China circulated freely in Europe at that time. It is hard to pin down which ones were the most instrumental in transmitting landscape design ideas, but a strong case could be made for a set of thirty-six copperplate engravings commissioned by the Kangxi Emperor in 1712. The Morgan’s set figured in the Romantic Gardens catalogue as an intriguing example of how Western technology could convey an Eastern aesthetic. The catalogue brought it to the attention of the sinologist Richard E. Strassberg, who described it and its cultural context in Thirty-Six Views: The Kangxi Emperor’s Mountain Estate in Poetry and Prints (2016). On the basis of his research, and the work of his colleague Stephen H. Whiteman, it is now possible to tell what was the original meaning of the thirty-six views, how they were translated into engravings, and how the engravings came to England.

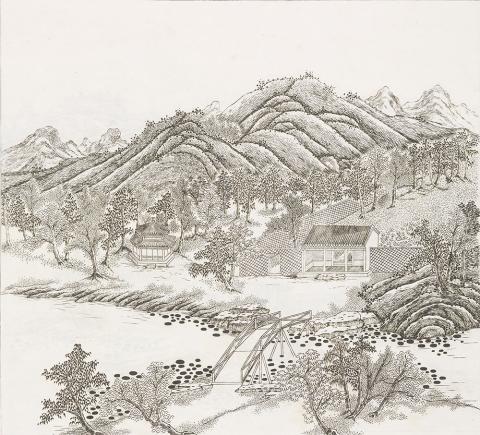

“An Immense Field with Shady Groves,” plate 35 in Views of Jehol (ca. 1714). Gift of Paul Mellon, 1980.

The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722) designed the Mountain Estate to be his summer residence, a garden complex with rustic villas, purpose-built hills, and artificial lakes situated in Jehol about 140 miles northeast of Beijing. Every year a grand procession of courtiers would accompany him to this picturesque locale. Here he could enjoy the simple life far from the stifling ceremonies and suffocating heat of the Forbidden City. His leisure became even more important to him during a stressful succession crisis caused by treasonous intrigues amidst rival factions in the imperial household. The Mountain Estate took on a symbolic significance, a place where the emperor could cultivate the traits of a virtuous ruler and fulfill his destiny to be an intermediary between heaven and earth. A patron of the arts with literary aspirations, Kangxi wrote poems to express the natural beauties of this landscape microcosm. In one of the poems, he ascends to celestial heights in a hilltop three-story pagoda, the Tower of the Supreme God, which gives him a panoramic view of the perfectly harmonized world beneath him. In another, “An Immense Field with Shady Groves,” he celebrates the humble pleasures of a melon patch in contrast to an adjacent field, a fine hunting park but also an allegory of ambition: he has been frugal and has refrained from building in that space.

He selected thirty-six poems for publication and had them illustrated by artists in his entourage. A team of block cutters produced woodcuts after the designs of the court painter Shen Yu (1649–after 1728), whose name appears in the last of the views. Despite delays—it took twenty days to cut a single block, and good blocks were in short supply—the Imperial Printing Office succeeded in producing 400 copies between 1712 and 1714, an accomplishment duly recorded in a colophon composed by the herald to the Crown Prince:

Now, by the favor bestowed upon us through Your Majesty’s edict, we append our names to the end of this work. At this, we are both joyous and ashamed, unable to contain our feelings.…We have seen all these Views with our own eyes, and yet are unable to capture them in words. Upon reverently reading the Imperial Poems, every green grove and misty spring suddenly fills our hearts. This place’s Views result from the natural life-force of Heaven and Earth and of the landscape; only Your Majesty’s brush could transmit the essence of these Views into words.

In addition to the woodcuts, the emperor ordered the Catholic missionary Matteo Ripa (1682–1746) to make copperplate engravings of the same thirty-six scenes. Ripa had some skill in oil painting but was only barely acquainted with engraving. But he took up this artistic challenge in the same spirit as missionaries who had impressed the emperor with their prowess in mathematics, music, clockmaking, and other European pursuits. The emperor asked him to teach intaglio techniques to Chinese apprentices, whose work can be discerned in some of the prints, including nine signed in the margin by Zhang Kui. Ripa struggled with the chemistry of the etching process. He had to build a rolling press and make his own ink. His first experiments with etching were not successful, and it seems that he abandoned that approach and did all or most of his engraving with a burin.

“Observing the Fish from a Waterside Rock,” plate 31 in Views of Jehol (ca. 1714). Gift of Paul Mellon, 1980.

Art historians have noticed that some prints stay close in style to the woodcuts and others adopt European visual conventions. The Europeanized views are more likely to contain shading, perspective, depth, contrast, and other graphic idioms not part of the woodcut tradition. The engraver may have wished to demonstrate the potential of intaglio technology and gratify the expectations of the emperor, who had seen what it could do in imported artwork. Ripa may have taken charge of more adventuresome prints and allowed his apprentices to render the other scenes by rote or interpret them with their own visual vocabulary. Perhaps his hand can be detected in the plate, “Observing the Fish,” a tranquil scene but far more dynamic than the corresponding woodcut. The pavilion looks the same, but the landscape around it has been transformed in the Western style with craggy rocks, luxuriant trees, and dramatic atmospheric effects in the sky. The engraver has animated the surroundings with additional pictorial content such as a flock of birds in the background and a school of fish in the lake, which is almost an empty space in the woodcut, but here ripples in the wind and shimmers as the light moves between the clouds. The poem calls for fish as well as birds “towing the clouds along.” In that respect, the engraving is a better illustration than the woodcut, which omits those telling details.

In April 1714, Ripa presented the engravings to Kangxi, who professed to be pleased and called them “treasures.” They were printed in batches, some on Chinese paper, some on European stock, for distribution among courtiers and members of the imperial family. Ripa sent a few sets to Europe including one addressed to the pope with a covering letter stating that he had printed seventy copies for the emperor. After Kangxi died in 1722, Ripa realized that Catholic missionaries would not be welcome in the new regime and decided to return home. He left Beijing in 1723 and booked a passage on an East Indiaman, which made a stopover in London. There he was entertained by the king, the directors of the East India Company, and other notables who wanted to hear about his adventures in China.

No doubt he gave away some sets of his prints as hospitality gifts. Art historians have debated the provenance of a set belonging to Richard Boyle, third Earl of Burlington (1694–1753), who plays an important part in garden history. Beginning in 1725, he designed pleasure grounds for his estate at Chiswick with formal elements in some places but mainly with the naturalistic features that came to characterize the English style. Alexander Pope dedicated to Burlington his famous verse epistle about the construction of country estates, in which he urges his like-minded patron to respect the “Genius of the Place.” (The Morgan has an autograph manuscript of this work.) Were Burlington’s innovations inspired by Ripa’s engravings? Unfortunately, there is no record of the earl’s encounter with the missionary and no way of dating when the engravings entered the Chiswick library. Two historians have argued against a Chinese connection.

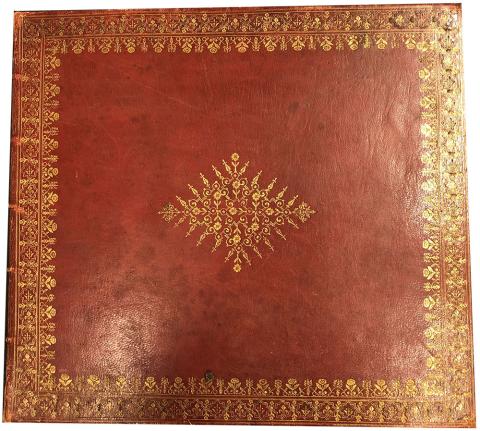

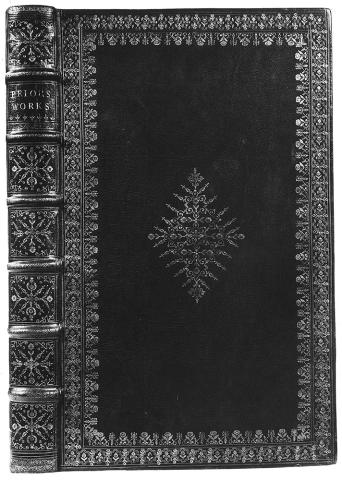

On the other hand, Strassberg detects similarities between the bindings of the Burlington set and the Morgan set. This is a promising line of research and deserves further investigation because the Morgan binding can be securely dated. An expensive production in gilt red morocco, it was decorated with roll-tooled borders and a diamond-shaped centerpiece in the Harleian style, which already suggests a date in the 1720s. That style was popularized by the famous Harleian library formed by the Tory statesman Robert Harley, first Earl of Oxford, and his son Edward, Lord Harley, who continued to build the library and commission bindings after his father fell from office in 1715. The bindings are amply documented in archives and the diary of Harley’s librarian. While working on the Romantic Gardens catalogue, I looked for more information in Bookbinding in the British Isles, a series of catalogues issued by the London antiquarian booksellers Maggs Bros. One of them contained just what I needed: an illustration of a handsome Harleian binding almost identical in materials and ornament. Covering a large-paper folio edition of Matthew Prior’s Poems on Several Occasions, it too is in red morocco, and the same tools can be seen in the border and the centerpiece. That edition is dated 1718 on the title-page but was not issued until March 1719. The copy in the Maggs catalogue contains an inscription indicating that it belonged to one of the original subscribers, who probably had it bound soon after publication. The endleaves are on the same premium-grade paper as the text. By inference, therefore, the Morgan binding can be dated in the early 1720s, about the same time that Ripa was passing through London. So, maybe there was a meeting of the minds between Ripa and Burlington, who admired the Views of Jehol and emulated them in his gardens at Chiswick. The evidence is still not conclusive, but it speaks to the mission of the Morgan, which collects, preserves, and interprets books as physical objects whose tangible attributes have cultural meanings. In this case, the gilt ornament on a binding helps to explain the diffusion of Chinese landscape aesthetics, the origins of the English garden, and, closer to home, the Ramble in Central Park.

John Bidwell

Astor Curator and Department Head

The Morgan Library & Museum