Shelby White & Leon Levy Fellow Kait Astrella with MS M.780 in the Sherman Fairchild Reading Room.

If you have ever experienced the particular disappointment of lending a book and never getting it back, you may just begin to understand the plight of medieval and early modern librarians and book owners—if you multiply your agony ad infinitum. The labor required to produce books and manuscripts made them objects of extraordinary value in great need of protection. Producing a book on vellum could take months or years and might cost twelve oxen, two hundred sheep, a whole farm or even a whole town (as a Gutenberg Bible might have)1. But if all other protections failed—chains, hiding places, lock and key—there was the book curse.

A book curse is any inscription explicitly threatening harm to those who would damage or steal a book. Before the advent of the codex, scribes used curses on bricks or tablets, slabs made of clay or stone, to protect whole temples or libraries. Perhaps the oldest known curse protecting a particular tablet2 was created for King Ashurbanipal of Babylon; it threatens the reader: “Whosoever takes [this tablet] away, or writes his own name instead of mine, may Ashur and Ninlil wildly and furiously reject him, and destroy his name and seed in the land!”3 Here exists not just a protection against damage but also against an erasure of authorship. The curse, in some ways, is a protection of a work’s provenance, or information about the origin of a work and who owns it.

Questions of provenance are particularly important to catalogers, which is the kind of librarian I am at The Morgan Library & Museum. As the Shelby White & Leon Levy Fellow in Manuscript Cataloging, my job is to create electronic records about objects so that information about them is preserved and becomes discoverable. In a cataloging listserv, our department received notice of a particularly good curse from Morgan Kirkpatrick at Princeton University, who asked: “Does anyone know a controlled term for book curses, or injunctions against thieves? I have a really great one that I’d love to make findable.” They proceeded to disclose the curse, which was really great:

Qui furabit hunc librum

Non videbit jesum Cristum

Certe ibit in infernum

Ibi stabit in aeternum

Ad exemplum ceterorum

per

Omnia saecula saeculorum

Amen

Put through Google translate, this Latin comes out to:

Whoever steals this book

will not see Jesus Christ

will certainly go to hell

will stand there forever

as an example to others

Forever and ever

Amen

If there are any errors in this translation, I think the general sentiment comes across.

Kirkpatrick was asking us for advice about how best to catalog this item, because they wanted to find a controlled term—a name, subject, place, genre, or form description that has been standardized, so that it appears the same way in catalog records across institutions. Catalogers are generally working to make legible what is special about an item, even if researchers are not seeing it in a reading room or on a screen. In our work, there are controlled vocabulary terms to describe if a manuscript has illuminations, if a book has a silver binding, if there are specific watermarks—such as an anchor in a circle surmounted by a six-pointed star. Many of these components tell us what is unique and identifiable about an item. Much cataloging has moved toward a sort of streamlined or copy cataloging approach in which there is little noted about a specific item. There is the specter of AI-generated records lurking over the cataloger’s chair.4 However, special collections cataloging requires a specificity that is only possible when a person is examining an item and weighing its attributes across various sources, many not online, to accurately describe it. To best describe book curses, it turned out, there was no controlled term to note their presence—making them difficult to find.

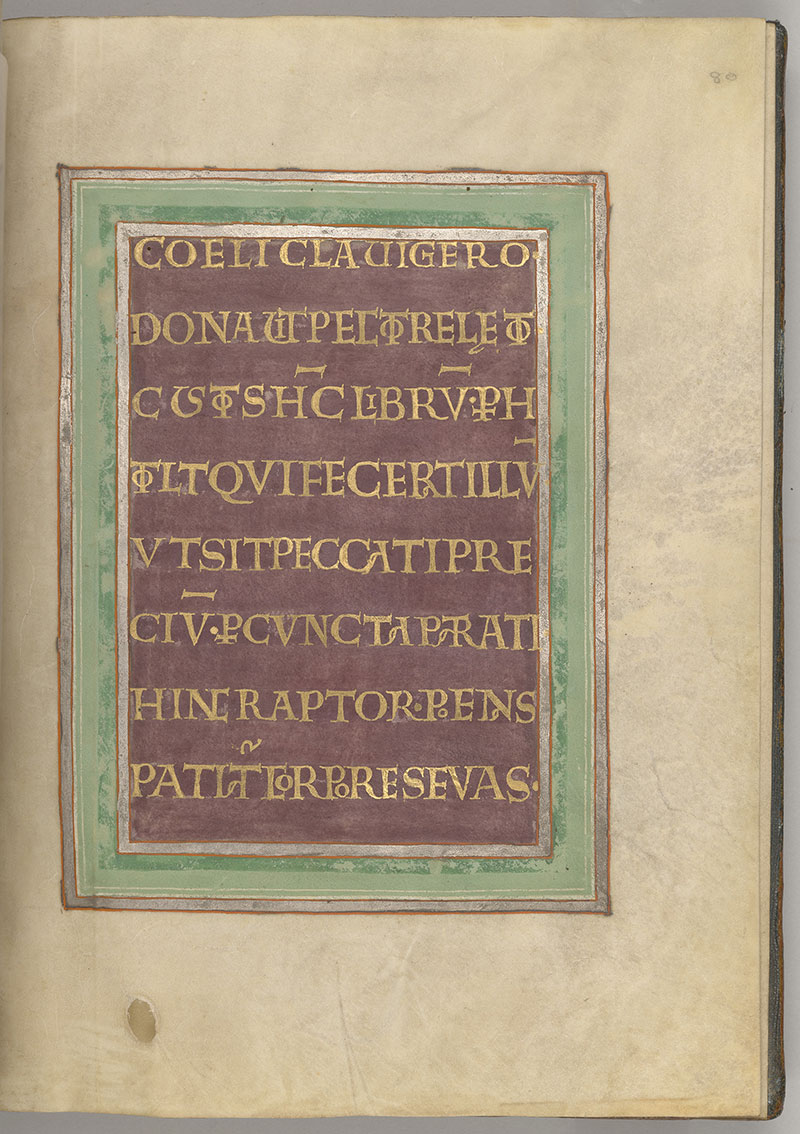

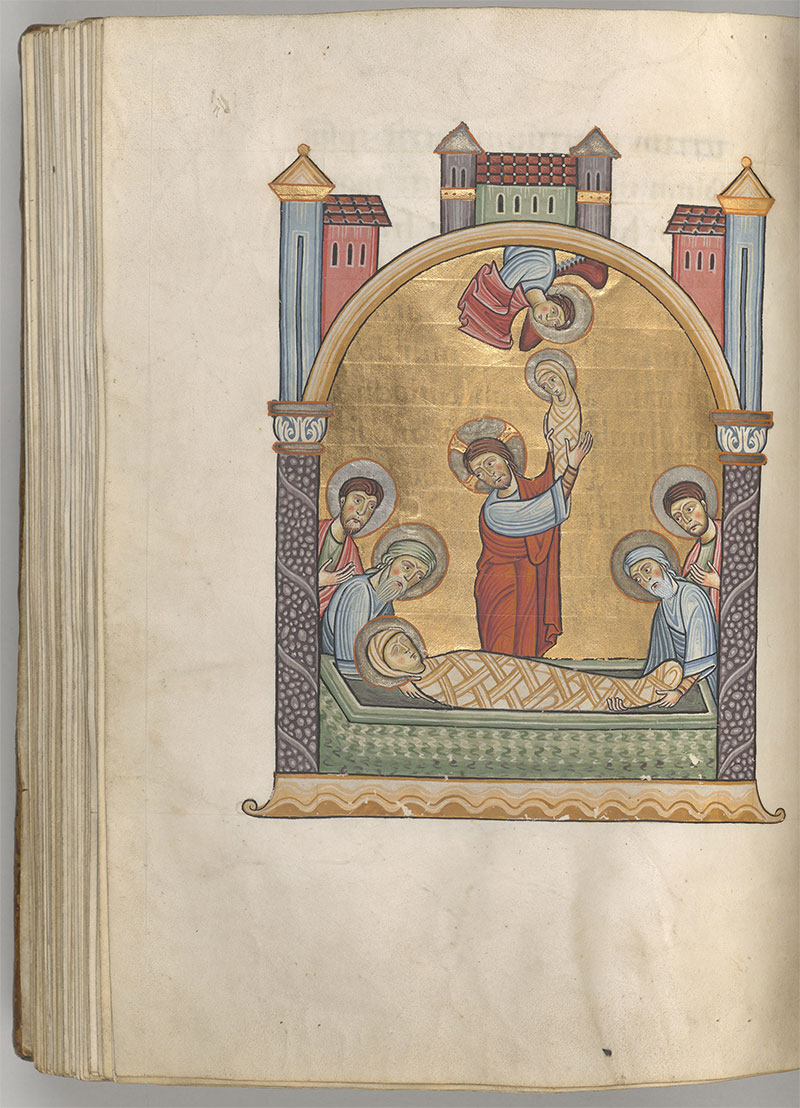

I wondered how many book curses the Morgan might have, because our collection contains so many medieval codices and early printed books. Of the eight books and manuscripts in the Morgan’s holdings that I could find with possible book curses through catalog searches5, two are incunables, five are from 1536–1558, and one is from 1896. I relied on two reference books that collect and analyze book curses to check for objects cited from the Morgan’s collection: Anathema!: Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses by Marc Drogin6 and Book Curses by Eleanor Baker7. Drogin cited the Morgan’s inscription of Perhtolt, custos (MS M.780, fol. 80r) as a particularly beautiful curse, rendered in gold lettering on purple vellum. The Latin translates to: “To the bearer of the keys to heaven the Guardian Perhtolt who made this book offers it with joyful heart in order that it may be an expiration for all sins committed by him. May he who steals it suffer violent bodily pains.”

Gospel lectionary (MS M.780, fol. 64v). Salzburg, Austria, 1070–1090. The Morgan Library & Museum. MS M.780. Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1933.

Example of an illuminated miniature. This one depicts a swaddled Virgin Mary in a sarcophagus, with Christ holding up her soul (also swaddled) toward an angel. More detailed description here. It is possible to view images of all the illuminations by going to the catalog record for the book.

Leafing through the book, it is not hard to see why such a strong malediction is justified. There are miniatures and illuminated capitals protected by small blue or cream silk sheets called curtains8. This particular curse seems to have worked, as the lectionary, written and illuminated at the Benedictine monastery of St. Peter in Salzburg, remained there until the Morgan purchased it in 1933. There is, however, one page missing that possibly contained a miniature. Perhaps someone is (or was) out there suffering violent bodily pains.

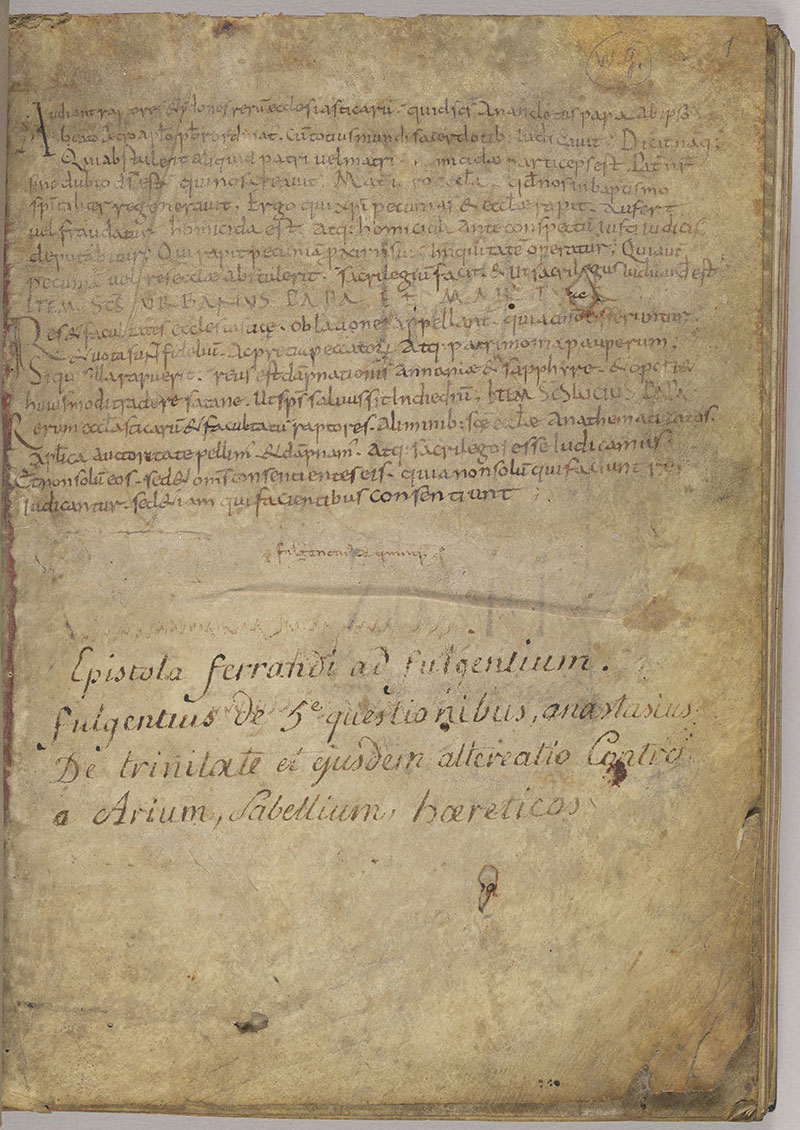

One of my catalog searches for “anathema” turned up a record for the De Trinitate miscellany from the ninth century (MS G.33). The record said it included an “anathema against those who plunder Church goods” (fol. 1). Emerald Lucas, Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, retrieved the item and set about making a first pass at a transcription and translation of the text. Although further research and translation work is necessary to determine if this might be a book curse or a more general injunction, Lucas’s preliminary translation work is a valuable start.

Likewise, if anyone accepts offerings or alms of the poor, which are offered for the redemption of the faithful departed, or annual or weekly offerings…

And converts what has been received for the salvation of the dead to his own use, let him be anathema maranatha (accursed, doomed to destruction).

But if anyone, unworthy of priestly office, presumes to be a priest, let him be struck with anathema.

If a cleric or priest, for the cause of a sacrament or the Eucharist or some other reason of religion…

Whoever communicates with the excommunicated, let them know they are under the same condemnation.

Not only those who do such things, but also those who consent to them, are judged.

While this particular anathema does not target book thieves directly, it does serve as an injunction against anyone who should disobey the Church or assume its authority. This book is a collection of religious tracts and letters by theologians, particularly defending the dogma of the Trinity. It is written on vellum in Caroline minuscule9, a hand created in Carolingian centers during the era of Charlemagne’s educational reforms and notable for its clarity. It also forms the basis of our own modern Roman lowercase alphabet. The rarefied production of this text and its subject matter make its anathema especially powerful, because it dooms anyone who would portend to wield the same authority, “priestly office” or even communicate with those who have been exiled from the Church community. This anathema in particular reads as an attempt at social control and betrays a fear of anyone who might try to usurp Church power.

Any threat to the objects themselves, possibly, was a threat to the knowledge stored within—only accessible as long as the book remained in the owner’s possession. The other “possible book curses”10 I came across were all from sixteenth-century France and were present in five volumes11 owned by the same family, Ramey, who may have made a practice of including book curses, although a researcher would have to verify the inscriptions flagged in our catalog. There are three leather bindings, one sheepskin and one vellum binding. The texts are often annotated and include works about ancient geography, rhetoric, and selected writing from Cicero and Isocrates.

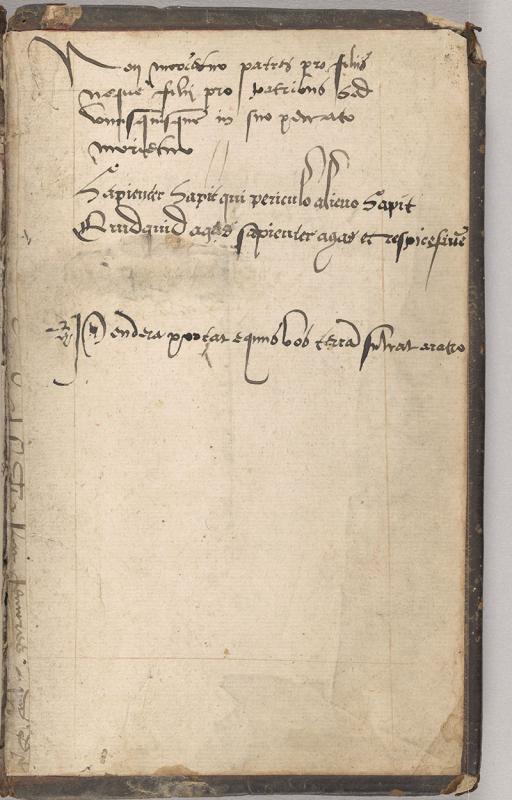

Mela, Pomponius. Pomponii Melae De situ orbis libri tres. Parisiis : Ex officina Christiani Wecheli ..., 1536. The Morgan Library & Museum. Lower cover of PML 125339.2.

Inscriptions (Latin proverbs) inside lower cover read: "Non p[?] patres pro filiis neque filii pro patribus suis sid"; second inscription unidentified; "Sapienter sapit qui periculo alieno sapit Quidquid agas sapienter agas et respice fine"; final inscription unidentified. More information in our catalog record.

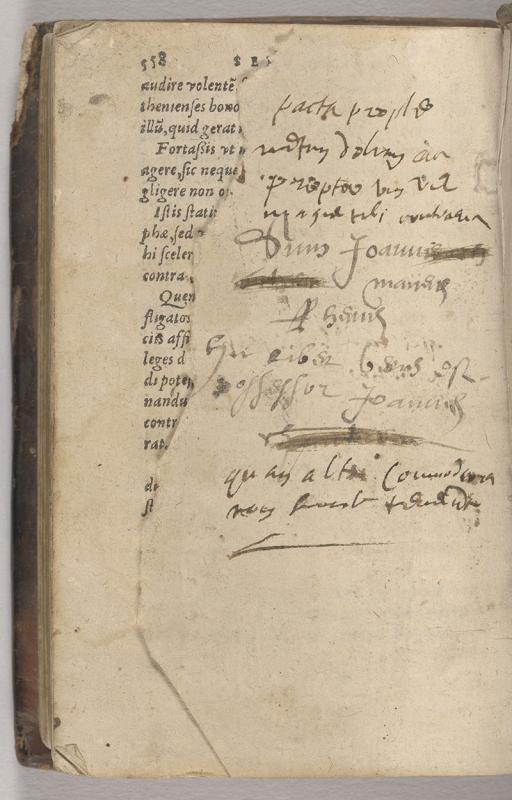

Demosthenes. Demosthenis ac Ciceronis Sententiae selectae : item, apophthegmata quaedam pia ex ducentis veteribus oratoribus, philosophis & tis, tam Graecis m Latinis ad bene que viuendum collecta : horum nomina sequens pagella indicabit.. [Lugduni? : s.n., 1558?]. The Morgan Library & Museum. PML 125315. Purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 1988–9.

Possible curse on the verso of lower flyleaf.

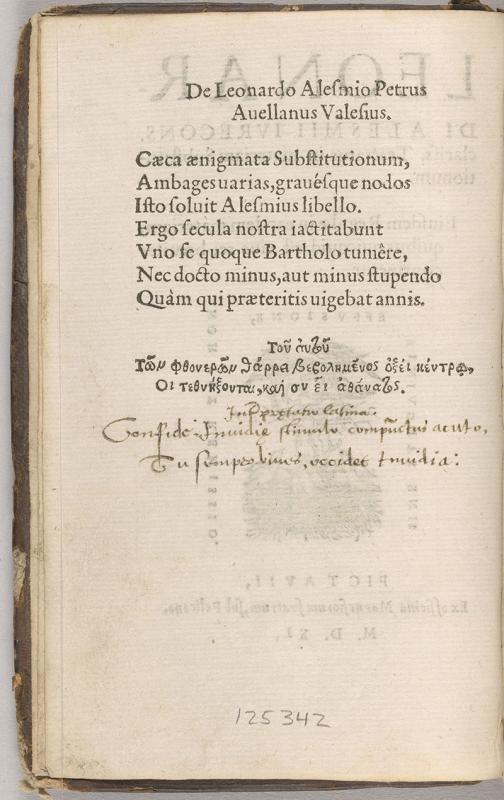

Aleme, Leonard. Leonardi Alesmii iurecons. clariss. Tractatus in materiam substitutionum., verso of title page. Poitiers : Ex officina Marnefiorum fratrum ..., 1540. The Morgan Library & Museum. PML 125342. Purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 1988–9.

Verso of title page: "In [?]tatio latina. Confide Invidie stimulo compu[n]ctus acuto, Tu semper bines occidet timidia:" possible translation of Greek printed text above, or book curse.

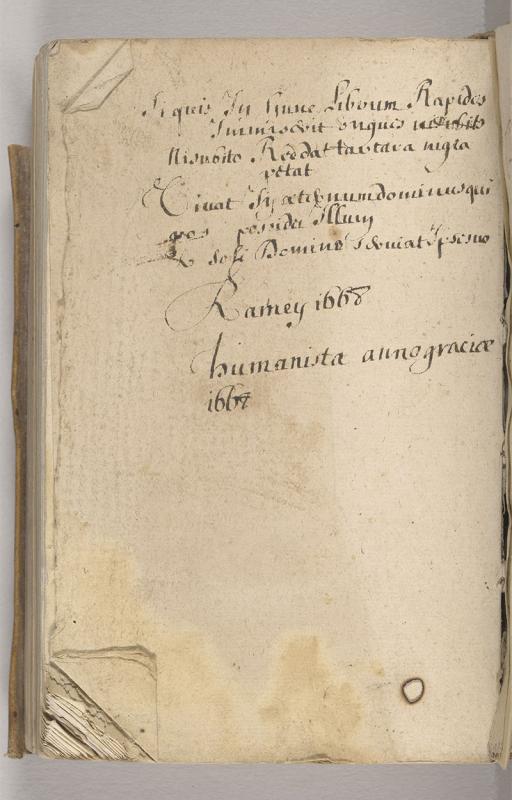

Isocrates. Isocratis rhetoris Atheniensis Orationes et Epistolae grauitatis & suauitatis plenae. Lutetiae [Paris] ; Ex officina lis Vascosani, uia Iacobaea, ad insigne Fontis, 1553. The Morgan Library & Museum. PML 129957. Purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2007.

Book curse dated 1668 and signed "Ramey ... humanista" on last flyleaf, repeated in part on upper cover (signed) and on first flyleaf (unsigned). Here you can also see a little bit of the velum Yapp-style binding and manuscript waste binding as well.

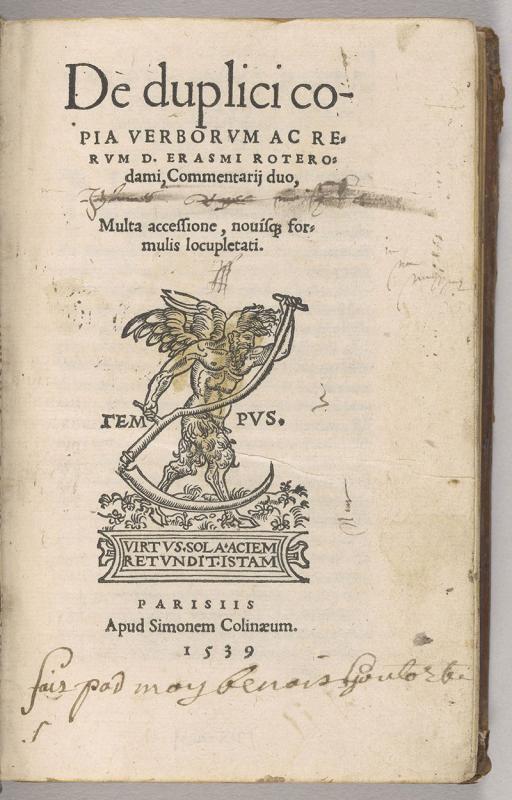

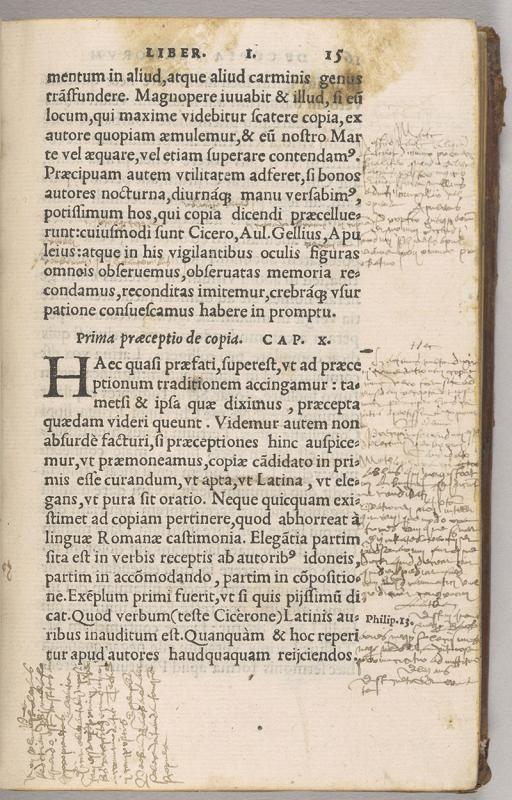

One volume (PML 125069) is a copy of De duplici copia verborum ac rerum, by the humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus. It is a text instructing readers on how to develop a style and make arguments—a kind of book that serves to beget more writing and knowledge production. The first sentence translates as: “The speech of man is a magnificent thing when it surges along like a golden river, with thoughts and words pouring out in rich abundance.” This copy also has marginalia and annotations throughout the text, suggesting that this was a much-used volume.

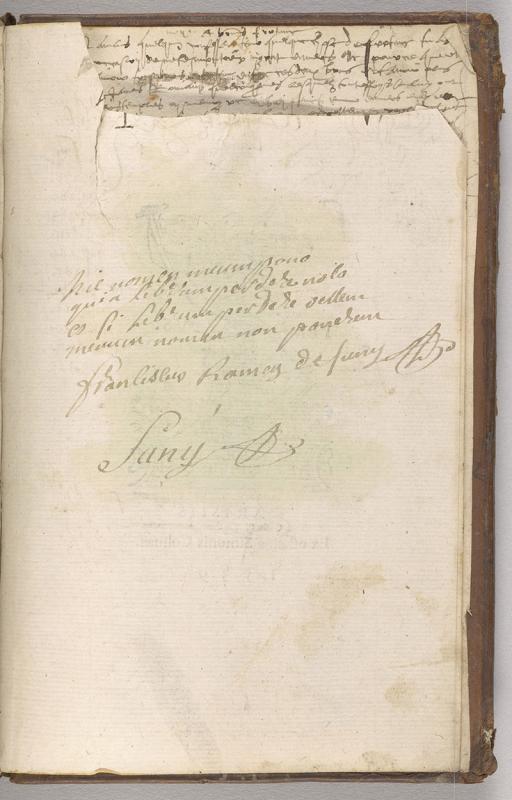

Erasmus, Desiderius, –1536. De duplici copia verborum ac rerum. Paris : Simonem Colinaeum, 1539. The Morgan Library & Museum. PML 125069. Purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 1988–9.

Possible book curse reads: "Hic nomen meum pono quia Librum perdere nolo et si Librum perdere vellem meum nomen non posser[?] / Franciscus Ramey de Suny [sic]."

Placing curses upon these objects, whether to earnestly keep them from becoming lost outside the library or as a playful familial gesture, suggests their high usage and value. These volumes reside within our vault at the Morgan, where they can be requested by researchers. So, even if we do not yet understand the curses the Ramey family likely employed, the Morgan is keeping their books as safe as humanly possible five centuries on.

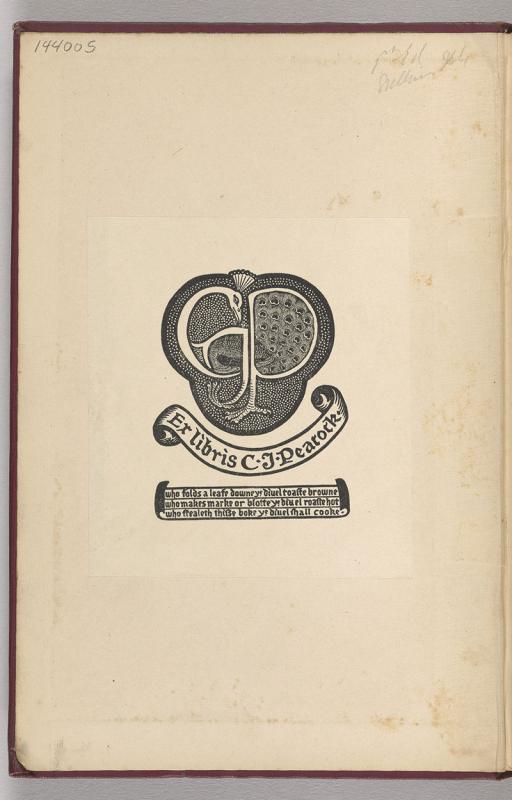

Cursing a book in order to keep it is not a practice lost to time. Both Baker’s book and Drogin’s playfully feature their own little maledictions. Likely readers of this very post might have inscribed threatening messages in a journal, as Aldus Huxley’s fictional character Jenny does in Chrome Yellow12: “Black is the raven, black is the rook / But blacker the thief who steals this book!” The Morgan has at least one example of a modern curse in the form of collector CJ Peacock’s bookplate (in PML 144005), a copy of Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest), fashioned in a medieval style13:

Ex libris C.J. Peacock.

Who folds a leafe downe

Ye dieul toaste browne,

Who make marke or blotte

Ye diuel roaste hot,

Who stealeth thife boke

Ye dieul shall cooke.

[Whoever folds a page down,

The devil toast brown.

Who makes a mark or blot,

The devil roast hot.

Whoever steals this book,

The devil will cook]

Coming to the end of my small and non-comprehensive investigation of curses in the Morgan’s collection, I felt that there were likely more undiscovered or at least unsearchable book curses in our catalog and elsewhere. In her paper14 on Edwardian Book curses, Lauren Alex O’Hagan points out that “limited studies have been carried out on book inscriptions” and that “[m]ore specifically, accounts of book curses and admonitions have only been humorous in nature.” In an effort to keep this door open not just at the Morgan but across many institutions, I submitted a controlled vocabulary term for “book curses” to the Getty’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) using many of the sources cited here so that other catalogers may begin to make these inscriptions more easily accessible to researchers. Morgan Kirkpatrick also continued an investigation into Princeton’s catalog, finding many curses within children’s books. They submitted a term to the Rare Books and Manuscripts Controlled Vocabularies (RBMSCV) that will soon be voted on. Both of us, in attempting to standardize a term that had not been previously codified, are highlighting what is special about individual items so that researchers can consider these unique aspects of the material.

This fellowship in particular has introduced me to the tools of cataloging beyond the walls of the Morgan. We are, as catalogers, facilitators of research; our work is sending a signal to the public that we have these special, unique objects, and we want the world to know so that they can be used, considered, and not destined to collect dust. I like to think about cataloging as a protection against dust, a protection against forgetting. Of course, these curses are entertaining to read about and encounter. But they are also important to the history of the book as a material object, because they emphasize the importance of ownership as well as the value of the bound book as a container of knowledge. We may no longer fear the consequences of such curses, but we would all do well to honor the lasting power of their afterlives.

Kait Astrella

Shelby White & Leon Levy Fellow in Manuscript Cataloging

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- Drogin, Marc. Anathema! Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses. Totowa, N.J.: Montclair, N.J: Allanheld, Osmun; A. Schram, 1983, 29–32.

- At the British Museum, K.155

- Translation from: Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal

- From what I can tell from the chatter of other professionals, most AI-generated records are riddled with errors and hallucinations. They seem to have issues understanding when to apply controlled vocabularies and aren’t particularly ready for wholesale bibliographic description, as shown in a library of Congress experiment last year with eBooks: Brador, Isabel. “Could Artificial Intelligence Help Catalog Thousands of Digital Library Books? An Interview with Abigail Potter and Caroline Saccucci | The Signal.” Webpage. The Library of Congress, November 19, 2024. The catalogers in this test were said to exhibit “curiosity and an open mind” about AI. There are likely just as many catalogers who possess a hostile mind about it.

- I used keyword and Boolean searches for the following terms: book curse; malediction; anathema; steal not this book; “suffer” AND “book”; “steal” AND “book”; “whoever” AND “steals”; “this book” AND “inscription”; “thief” and “book”; “bookplate” AND “eye” (in search of a known bookplate with a curse); dire oath; dear oath; dieren eet.

- Ibid.

- Baker, Eleanor. Book Curses. Oxford: Bodleian Library Publishing, 2024.

- There are many examples of curtains in the Morgan’s collection. Though not imaged, M.780 is included in: Adams, Morgan Simms. “Identifying Evidence of Textile Curtains in Medieval Manuscripts in the Morgan Library & Museum.” In Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding, edited by Julia Miller, vol. 6. The Legacy press, 2020. Adams was a Pine Tree Foundation Post-Graduate Fellow in Book Conservation in the Thaw Conservation Center (2013–2015) and in this paper seeks out instances where curtains had been removed. Adams mentions that in M.780, curtains are attached by stitches in one upper corner. If you are curious about how curtains look in general, the digital facsimile of MS M.710.

- The entry for Caroline minuscule in AAT has many examples.

- In the MARC record’s 500 notes section, the inscriptions are described as “possible book curse”.

- PML 125339.2; PML 125069; PML 125315; PML 125342; PML 129957

- Baker, p. 107. The Morgan has a 1921 edition, PML 135564.

- Transcription from Baker, p. 106.

- O’Hagan, Lauren Alex. “Steal Not This Book My Honest Friend : Threats, Warnings, and Curses in the Edwardian Book.” Textual Cultures 13, no. 2 (October 9, 2020).

Special thanks to Director of Collections Information Maria Oldal, Gordon Ray Cataloger Sandra Carpenter, and Special Collections Cataloger Lenge Hong for all of your help and encouragement during the course of this fellowship. I am honored to have learned the art of cataloging from you all.