This blog post is an excerpt from the catalogue accompanying the Morgan’s exhibition The Drawings of Al Taylor.

In 1991, the German art dealer Fred Jahn visited Taylor’s studio and bought sixty-eight drawings. He subsequently offered to show the artist’s work regularly in his Munich gallery. From then on, Taylor was able to devote himself to his art. He had his first museum exhibition in 1992, at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland (Fig. 13). This was a productive year for Taylor. In addition to completing The Peabody Group, he embarked on several new series, the most singular of which was inspired by a fish replica retrieved from a trash bin outside a bar. The artist’s description of the circumstances of his find and the gestation of the drawings is worth quoting at length, as it illuminates his thought process.

“I found a stuffed swordfish about my size in a trash barrel on the street. It was crushed in half and just laying there. I took it home and waited 6 months trying to figure it out. (I knew I liked the airbrush painting.) I could only come up with drawing of the fish breaking thru a plane. I liked it but it was becoming embarrassing to invite other artists over and they would see a broken swordfish with no fin in the corner. One day I decided to throw the fish out and sawed it into sections to fit into a trash bag. When I was sawing I realized that I had never looked inside a swordfish stuffed or alive and to my surprise it was all plaster and burlap. As interesting as it was, I kept cutting and was left with 5 parts, and threw them into the trash bag. I had had enough of this. The phone was ringing. I got off the phone, pulled the fish out of the trash for a second time and laid it out on the floor, trying different orders. No good. Then I tried to make some Naumans out of it. No good. Even worse. Then I realized that I could stretch the fish. As it became longer I thought of all the stories that I have heard from fishermen who catch a fish and as time passes seem to make the fish longer with each telling of the catch. OK. I liked that fact of a lie. I then thought I will have to put this stuffed fish up on the wall in its stretched position to make the (?) (story) complete. It came from the wall, it should go back to the wall. How to do that. I had hollow parts so I passed a wire thru them. The wire was too long on the first part and formed a large loop which immediately took on aspects of being the sail of a swordfish so I made each part with a sail except the head. Now I draw this 20’ fish again & again. I am not sure of what the next step will be.”

By the end of this account, Taylor was spinning his own fish tale, exaggerating the size of his “catch” from six to twenty feet.

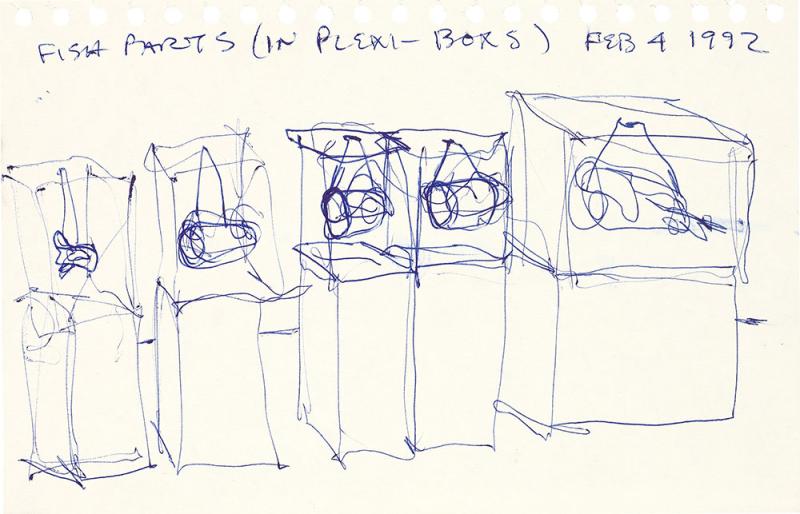

Small sketches record his experiments with different arrangements of the fish parts. In one of them, they stand vertically on a horizontal plane, following a fairly conventional still-life arrangement (Fig. 14). In another, he imagined hanging the parts along a vertical axis (Fig. 15). Finally, Taylor opted for a horizontal disposition, stretching the fish over nearly twelve feet, as it appears in a sketch in which he noted the size of each part and of the spaces between them (Fig. 16). He tried one more concept in a quick ballpoint pen study, dated 4 February 1992 (Fig. 17), in which they hang in Plexiglas boxes on pedestals (anticipating Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde). Taylor never had the opportunity to exhibit the sculpture—partially visible in a 1993 photograph taken in his studio (Fig. 18)—but the subject yielded a series of extraordinary drawings of great virtuosity. The most poignant among them feature one or two fish parts, hanging by a wire, isolated and imbued with a profound feeling of desolation.

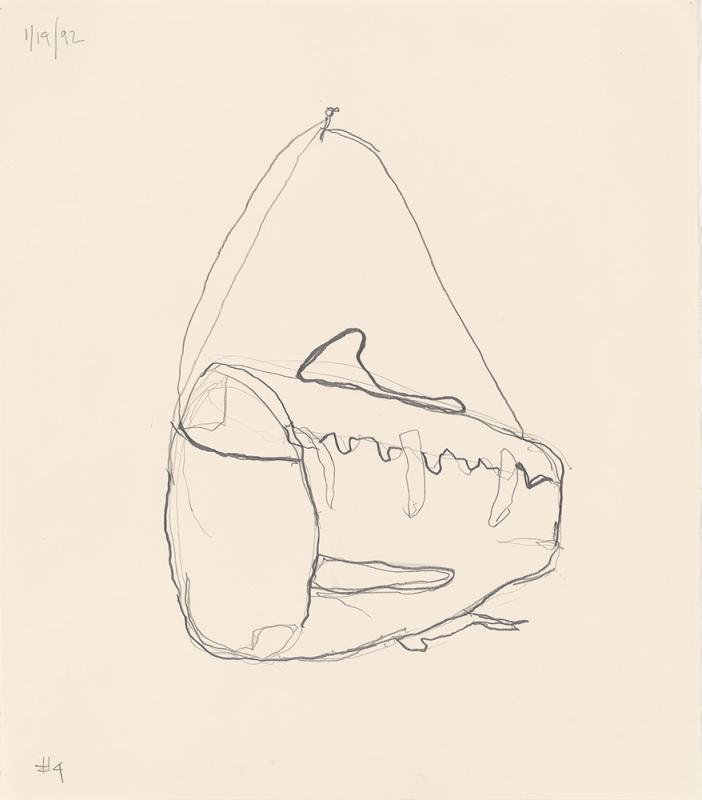

A set of four sheets at different stages of completion allows us to follow Taylor’s process. Two sheets show that he began with a contour drawing in graphite pencil, using two different degrees of softness to modulate the thickness and darkness of the line (Figs. 19–20). The two other drawings were reworked the following day (according to dates inscribed at upper left), when he applied ink and toner over the underdrawing to suggest volume and create a strong chiaroscuro effect. The fluidity of the application, especially where the solvent used to fix the toner ran down the lower part of the sheet, gives the impression that the fish has just been pulled out of water and is still dripping.

These drawings are among Taylor’s most representational works. Their painterliness calls to mind such Old Master antecedents as Jean Siméon Chardin’s The Ray, in which the eviscerated fish that dominates the picture hangs from a hook on the wall. Ewa Lajer-Burcharth has described Chardin’s “tactile mode of painting”—his reliance on visible brushwork to convey the very texture of the object, appealing to a sense of touch as much as vision. Chardin’s fish appears all the more real that its death is palpable, Lajer-Burcharth notes: “Death . . . penetrates the very process of painting . . . becomes inseparable from the very materiality of the painting.” Taylor’s painterly treatment achieves a similar effect, breathing life, as it were, into the plaster fish through the tangible evocation of its dead body. The free handling and use of chiaroscuro also relate Taylor’s drawings to the tradition of wash drawings to which belong some of his favorite Old Masters, notably Rembrandt and Goya. Like Goya, Taylor relied on the loose gesture of the brush, bare background, deep shadows, and bold black-and-white contrasts to heighten the drama of the scene. In Taylor’s drawings, the surrounding void and the crudeness of the wire and nail by which the fish parts are suspended lend the image a degree of pathos not found again in his work until the Bondage Duck series of his last year.

Due to their subject and high level of naturalism—enhanced in a few works through the addition of collage elements—the fish drawings stand apart in Taylor’s production. Most of the works he created during the 1990s were based on more trivial objects that he turned into series at once absurd and playful. The transformations could be minimal, as in the curling tabs of Tide laundry detergent boxes that gave rise to luscious and elegant drawings. Taylor was seduced by the spiral shapes these colorful tabs would take when pulled to open a box. Other transformations involved more elaborate operations. In the Pass the Peas series—likely inspired by James Brown’s 1972 tune Pass the Peas—Taylor fixed small plastic rings at various intervals along a coiling wire or telephone cable. The drawings, in some of which the peas are rendered with small drops of ink or watercolor, underscore the continuity between this series and the earlier stain and puddle drawings. Working in sequence, Taylor followed the course of his thoughts and imagination as they crystallized around the possibilities a particular object or event offered. “A drawing feeds another drawing till you get to a situation that requires something else,” he explained. “Then, that feeds another type of drawing, which finds other drawings till you reach another situation. Etc.”

One of Taylor’s sketchbooks contains the following text he copied (approximately) from Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel The Secret Agent. Taylor omitted the opening of the sentence that introduces the character Stevie, describing him as:

seated very good and quiet at a deal table, drawing circles, circles, innumerable circles, concentric circles that by their tangled multitude of repeated curves, uniformity of form, and confusion of intersecting lines suggested a rendering of cosmic chaos, the symbolism of a mad art attempting the inconceivable. The artist never turned his head; and in all his soul’s application to the task his back quivered, his thin neck, sunk into a deep hollow at the base of the skull, seemed ready to snap.

While the observer in the novel equates circle drawings to “a form of degeneracy,” Taylor, whose art abounds in circular forms, would have felt an affinity with the mad draftsman. Wheels, hula hoops, rubber tubes, tin cans, and all kinds of spirals found their way into his constructions and drawings. “The reason for this,” he offered, “must be that round things don’t have a traditional edge: they look pretty much the same from a lot of different angles.” Issues of perception were central to Taylor’s formal reflection. He was curious as to how things were seen from different vantage points and how certain factors—such as wearing glasses—affected perception. In several drawings of 1993, he materialized vision through a succession of circles of increasing sizes. In his 3-D constructions, he would take all points of view into consideration. “Like a pool player, I want to have all the angles covered,” he said.

In the drawings, too, he explored different perspectives. His compositions with tin cans offer a case in point. While in Munich in 1994, preparing for an exhibition at Fred Jahn’s gallery, Taylor, with the help of a local bartender friend, had gathered empty cans of various dimensions, with which he built complex installations. Untitled (100% Hawaiian), for instance, balances two open cans with their lids partly detached between two vertical wooden boards. The cans are suspended at the center of a network of copper wire, green plastic wire, and black wire, as noted on an installation drawing. The position of each element in space is carefully recorded through measurements from the floor and between the different parts. The related drawings, according to Jahn, were not created before or after the sculpture but at the same time, while installing the piece, in a back and forth between two and three dimensions that was typical of Taylor’s process.

One of the finished drawings made in connection with Untitled (100% Hawaiian) focuses on the cans at the center of the piece. Paying particular attention to the effect of light on the reflective aluminum surface, Taylor used a variety of marks to depict the shadows on the round shapes, relying on the white of the paper to heighten the contrast of light and dark. He also made effective use of the properties of each medium. On the lid at bottom left, for instance, he drew in pencil over gouache, exploiting the characteristic shininess of graphite to render the metallic surface. The emphasis on reflected light bouncing around the cans rather than on the precise outlining of the volumes in space is typical of a painter’s drawings. In the traditional conflict between draftsmanly and colorist modes of drawing, Taylor sided with the latter. His predilection for roundness is in keeping with the colorist’s approach, which favors luminous and shimmering surfaces over the evocation of solid forms. Only the wires that connect the cans to the edges of the sheet are materialized with firm, uninterrupted lines, enhancing, by contrast, the painterliness of this unusual still life.

Images

Debbie Taylor, figure 13; Glenn Steigelman, figures 14, 15, 16, 17; David Britton, figure 18; Graham S. Haber, figures 19, 20.

Isabelle Dervaux

Acquavella Curator and Department Head

Modern and Contemporary Drawings