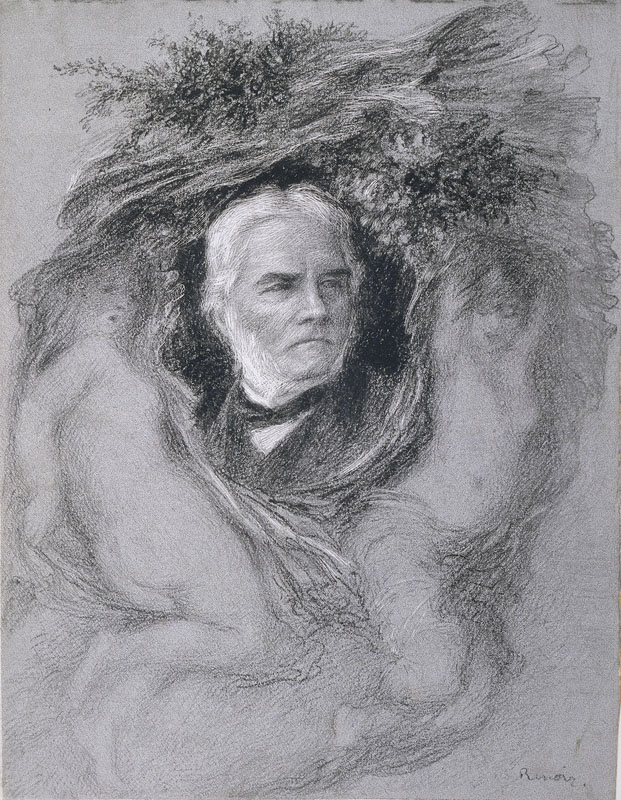

Listen to co-curator Sarah Lees discuss a portrait Renoir made for reproduction in a journal

In 1879 Renoir became a contributing illustrator to the new literary and artistic journal La Vie moderne. This portrait of fellow artist Léon Riesener (1808–1878), who had died a year earlier, was Renoir’s first contribution. Because of the technological limitations of photomechanical reproduction at the time, Renoir had to use a heavy paper prepared with a pre-printed matrix of black ink dots, on which he could add dark lines or scratch away white lines. Although he complained about the difficulty of the technique, he successfully captured Riesener’s likeness, and he made several more drawings of this type.

Léon Riesener, 1879

Illustration for La Vie moderne, no. 2, April 17, 1879

Black crayon with scratching out on coated paper (scratchboard)

Bequest of Selma Erving, class of 1927, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, SC 1984.10.57.

In 1879, the publisher Georges Charpentier and the writer and editor Émile Bergerat launched a new literary and artistic journal called La Vie moderne, and recruited Renoir as a contributing illustrator, along with his brother Edmond as a writer. The first drawing Renoir published in the journal was this portrait of fellow artist Léon Riesener, which appeared on the cover of the April 17, 1879 issue, about a year after Riesener’s death. It accompanied an article that briefly mentioned the sale of Riesener’s studio contents and personal collection that had taken place the week before. Bergerat, the editor, wanted to distinguish La Vie moderne from other illustrated publications, most of which employed printmakers specialized in wood engraving to copy artists’ images, so he chose an innovative photomechanical process that reproduced drawings directly, without the intermediary of a copyist. Initially, though, technological limitations meant that artists had to use paper pre-printed or embossed with patterns that produced a gray background, which could be drawn on to produce darker lines or scratched into for white highlights, as Renoir did here. He and other artists found it a difficult process, but just a few years later, the technology advanced so that drawings made on standard paper in more nuanced tones with chalk or ink would reproduce clearly after being photographically transferred to a printing plate. Renoir’s subsequent drawings for the journal—two of which are on view nearby—were made with this more versatile process.