Listen to co-curator Juliette Wells explain a popular myth about Jane Austen’s letters.

PRIME PEOPLE-WATCHING

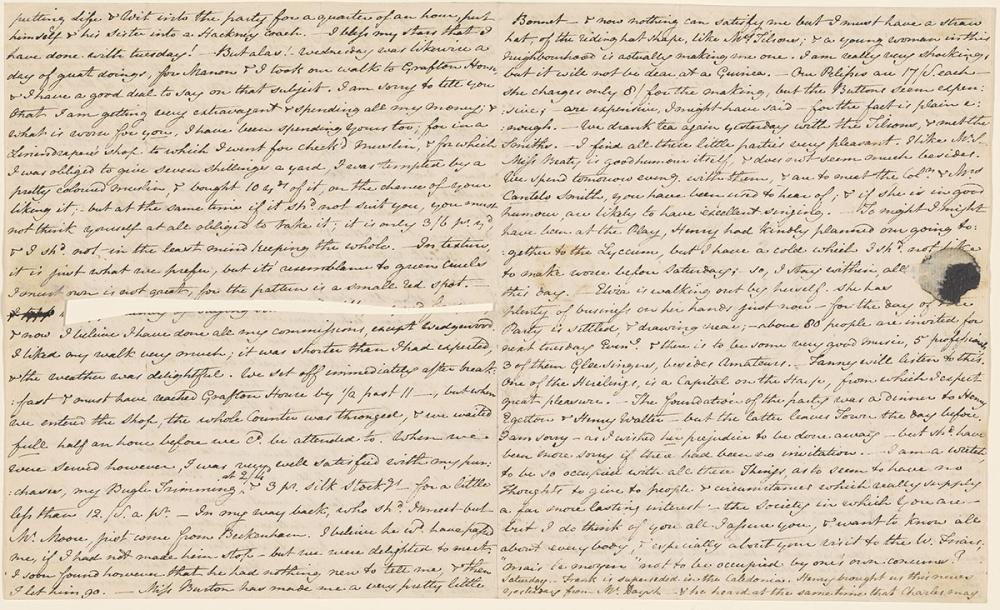

When staying in London, Jane Austen took advantage of the city’s culture. She confessed to Cassandra, however, that at museums and galleries, “my preference for Men & Women, always inclines me to attend more to the company than the sight.” Jane anticipated “excellent singing” at one upcoming gathering and “great pleasure” from a professional harpist at another. A cold prevented her from attending a play with Henry. The sentence cut out from this page likely contained an uncharitable remark about a relative. After Jane’s death, Cassandra selectively censored some letters that she judged to be otherwise worthy of preservation. She is thought to have destroyed many others to safeguard her late sister’s privacy.

Jane Austen (1775–1817)

Autograph letter to Cassandra Austen, London, April 18–20, 1811

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. P. Morgan Jr., 1920; MA 977.27

It has long been believed that after Jane Austen died, Cassandra destroyed many, if not most, of her sister’s letters. Recent biographical films and novels have reinforced this notion in the popular imagination. However, there is no conclusive evidence that Cassandra did so.

Caroline Austen, the niece whose manuscript recollections are on display earlier in this exhibition, is responsible for originating this myth. In 1867, Caroline recorded that Cassandra “burnt the greater part [of Jane’s letters], (as she told me), 2 or 3 years before her own death” (in 1845). Caroline’s account was repeated and embellished by family members in later generations.

Fewer than two hundred letters written by Jane Austen survive. Scholars estimate that she likely wrote a few thousand letters during her lifetime, based on how frequently she wrote to various family members when apart. Of these, the Morgan holds fifty-one: the largest group of Jane Austen letters in any collection in the world.