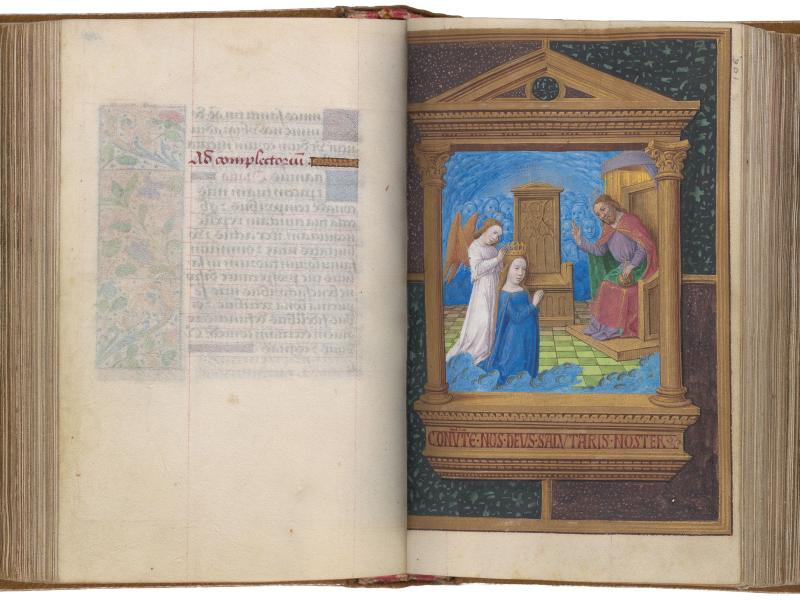

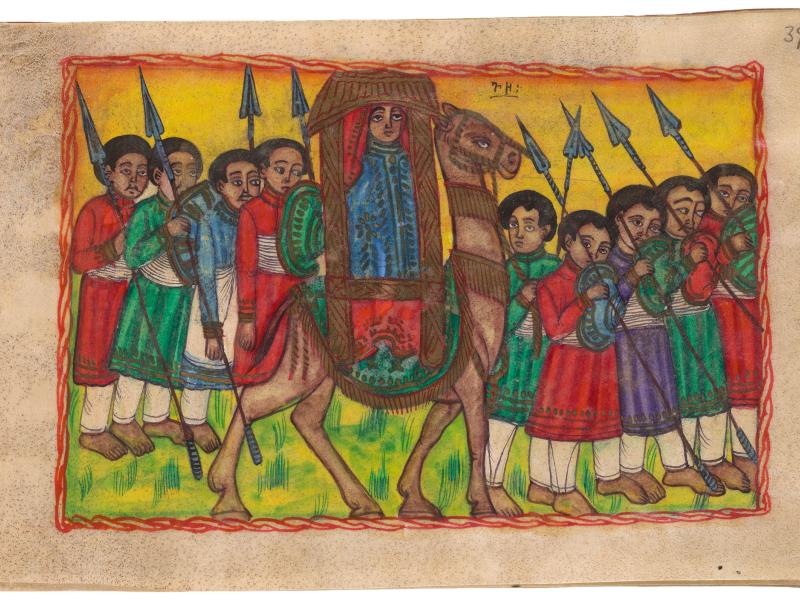

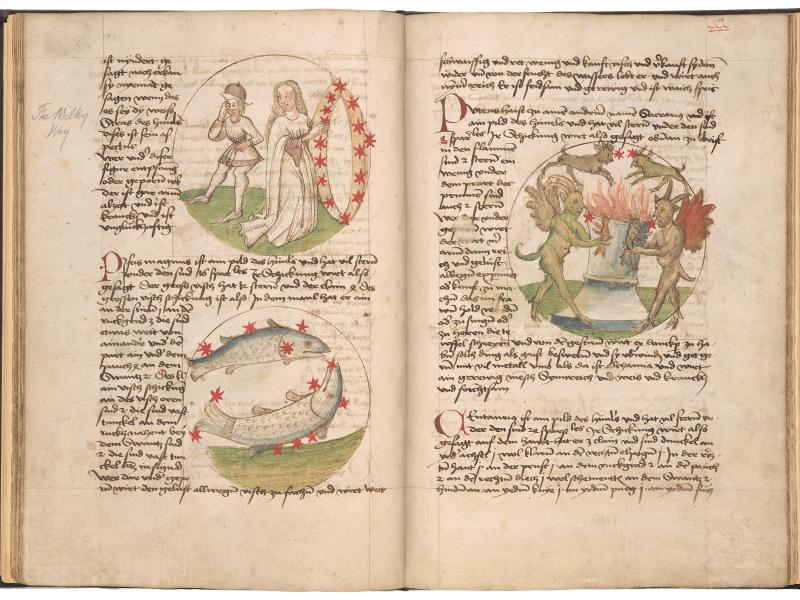

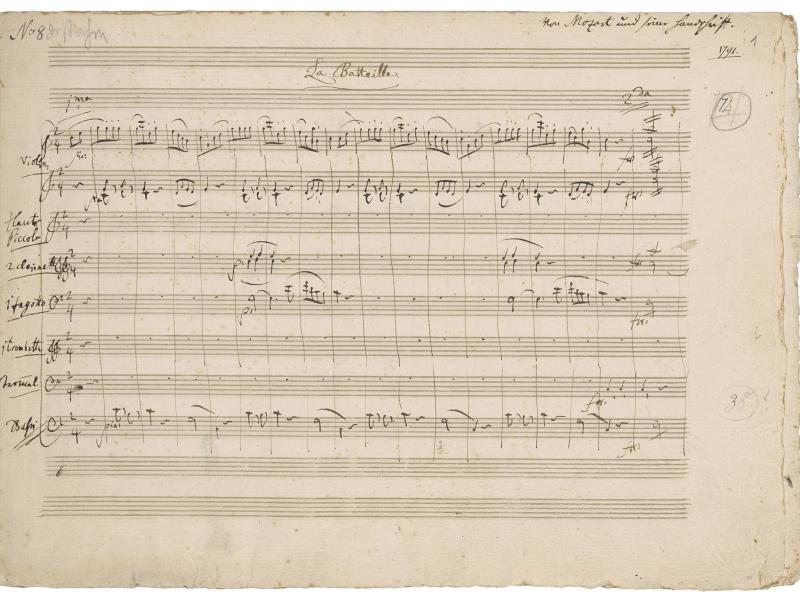

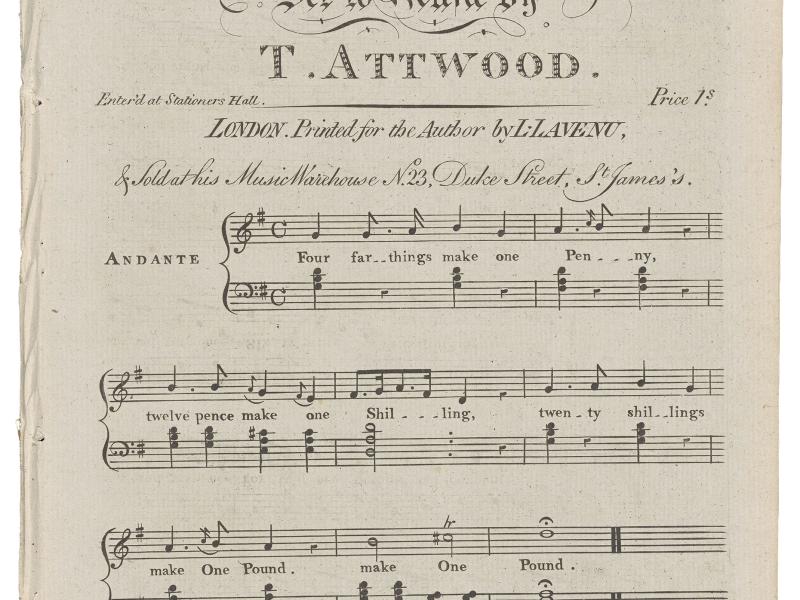

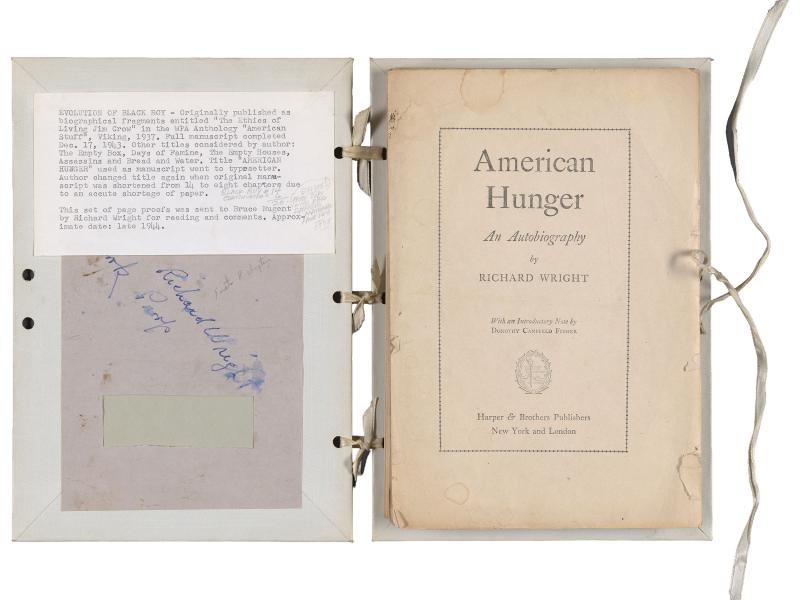

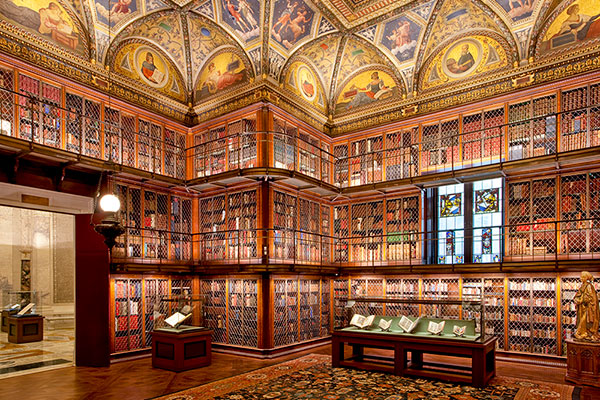

Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of the collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and Renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, literary manuscripts and correspondence, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items, to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, and to tell the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Here are some highlights of the rotation currently on view in the East Room and Rotunda.

Exhibition location:

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library

See map

Collections Spotlight is funded in perpetuity in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker.

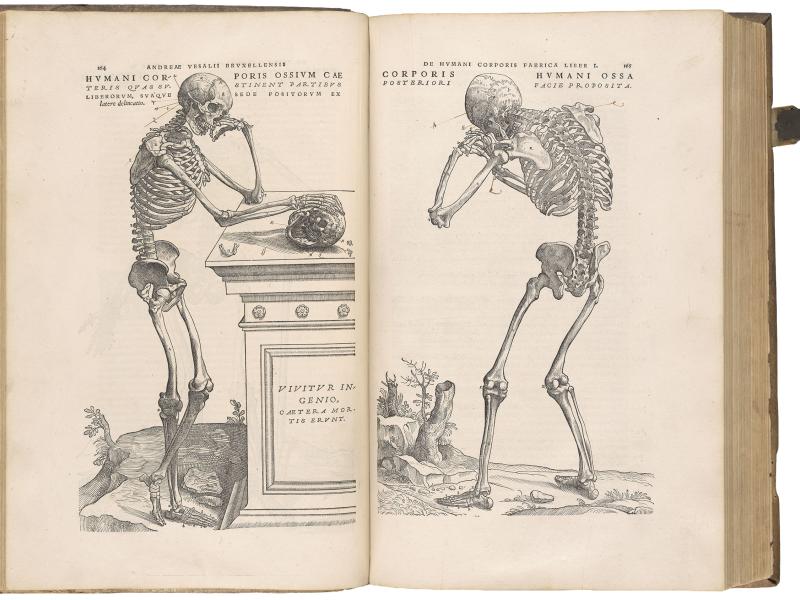

Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), Basel: Joannes Oporinus, 1543. Purchased in 1927; PML 24798