This is a guest post by Jarrett Moran, a doctoral candidate in History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Bring up the nineteenth-century British critic of art and society John Ruskin and there are a few stock stories that get repeated: an art history student might think of J. M. Whistler suing him for libel after Ruskin described his Nocturne in Black and Gold as “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face,” while a literature student might think of the “pathetic fallacy,” Ruskin’s term for poetic writing that attributes human emotions to the natural world. And often enough, someone will recount the apocryphal story about Ruskin’s marriage to Effie Gray failing because his studies of Greek sculptures had not prepared him for the existence of women’s body hair.

Beneath these familiar set-pieces, how to tell the story of Ruskin’s life, and which sources to use in doing so, has been a source of contention for biographers ever since his late-nineteenth-century disciples E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn edited the thirty-nine-volume Collected Works. Cook and Wedderburn consolidated a fragmentary and puzzling legacy into that of a monumental Victorian sage, one who conveniently anticipated their own progressive-liberal political beliefs. In the process, they tended to suppress the letters and manuscripts that embarrassed them or distracted from the image of Ruskin that they wanted to convey. They avoided heated letters between Ruskin and his father, who felt betrayed by the controversial critiques of political economy that his son insisted on publishing. Ruskin’s editors also suppressed the disillusionment that he experienced in discovering the erotic drawings of his hero, the painter J. M. W. Turner, a startling blow to his belief that Christian morality and artistic achievement were one and the same.

The Morgan has in its collection the manuscript of a 1400-page unfinished biography of Ruskin left by Helen Gill Viljoen (pronounced “fil-yoon”), an English professor at Queens College in New York from the 1930s to the 1960s, who became convinced that the letters and manuscripts missing from Ruskin’s Collected Works contained clues to some of the central preoccupations of Ruskin’s life. She first encountered these letters in a 1929 trip under the guidance of Ruskin’s friend and biographer W. G. Collingwood to Ruskin’s decaying house in the village of Coniston in the Lake District. Subsequently, as Ruskin’s manuscripts were further dispersed in auctions to collectors, she pursued her Ruskin biography in the archives of American institutions, particularly the Morgan Library, devotedly lugging her typewriter on the subway from her apartment in Flushing to the Reading Room.

Figure 2: Portrait of Gordon Norton Ray from Books As a Way of Life: Essays by Gordon N. Ray, The Grolier Club, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, 1988.

In recent years, James L. Spates has taken up Viljoen’s Ruskin scholarship and edited portions of it, even as more Ruskin letters have come to the Morgan from private collections in the years since Viljoen was preparing her biography. One of the collections that I worked with this fall came from the NYU professor Gordon Norton Ray, who, before his death in 1986, kept thousands of manuscripts and around ten thousand letters in his Sutton Place apartment in Manhattan. The material in some of these collections is sparsely documented, and I have been adding more context to the catalog entries for the Ruskin letters in order to make them more accessible to researchers and curators.

As the capacity of the Reading Room at the Morgan was curtailed this fall due to the COVID-19 pandemic, my experience working with the Ruskin materials at the Morgan was quite different from Viljoen’s. I did most of my research from home using scans of the letters, logging into the Morgan’s cataloging system remotely from my laptop and making occasional trips to the Reading Room to fill in missing details. On my Reading Room days (thankfully carrying a laptop on the subway rather than a typewriter), the other CUNY fellows and I worked at separate tables spaced well apart, arriving at scheduled intervals so as to avoid passing each other on our way in and out.

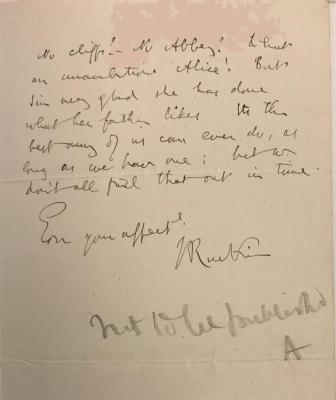

After spending the fall, virtually and in person, with a few collections of Ruskin letters, I saw glimpses of these other dimensions of Ruskin’s life, the ones absent from Ruskin’s Collected Works. One 1874 letter to the writer Arthur Helps, which arrived at the Morgan as part of the Ray Collection (MA 14317), bears the mark of this editing explicitly: “not to be published” written across the back in thick pencil, signed with the initial “A,” an annotation that I suspect was made by Alexander Wedderburn while selecting which letters to have transcribed for the Collected Works.

Figure 3: Page from an 1874 letter from Ruskin to Arthur Helps, with the penciled annotation “Not to be published.” (MA 14317)

Ruskin wrote the letter in an exuberant, giddy tone, inviting Helps to come see his favorite dancer, Kate Vaughan, in a pantomime:

Won’t it be—astonishing—to find ourselves there—philosophically— Have you really not seen Kate Vaughan dance, yet? My goodness!

The letter touches on a few of the subjects that Cook and Wedderburn tried to keep out of the Collected Works, Ruskin’s lowbrow enthusiasm for pantomime and Kate Vaughan’s dancing, as well as his fraught, regretful relationship with his father, which Ruskin obliquely alludes to after playful banter about a trip to the shore that Helps had recently taken with his daughter Alice.

But I’m very glad she has done what her father likes. It’s the best any of us can ever do, as long as we have one; but we don’t all find that out in time.

It’s an abruptly dark and introspective turn to an otherwise jocular invitation to a panto. Many of Ruskin’s correspondents from the 1870s would have been familiar with these moments, when a seemingly quotidian letter would shift into the melancholy or apocalyptic.

Helps’ reply is, satisfyingly enough, reproduced in the diary from Ruskin’s house in Coniston that Viljoen painstakingly edited in the 1960s and which Yale University Press published in 1971. Thanks to Viljoen’s volume, I know that Helps couldn’t see the pantomime with Ruskin after all—he had a prior engagement “to take the chair at a great public dinner”—but he approved of Ruskin’s sentiments about fatherhood. The Morgan’s collection continues to add pieces to the puzzle of Ruskin’s life that Viljoen began assembling decades ago, during many trips to the Reading Room.

Jarrett Moran is a doctoral candidate in History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, where he is writing a dissertation on the history of the concept of culture in Britain in the nineteenth and twentieth century. He has an MA in Modern European studies from Columbia University and a BA in Ethics, Politics, and Economics from Yale University. He was a Writing Across the Curriculum Fellow at Baruch College and has taught courses on the history of British radicalism and empire at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He is currently a Fellow at the Graduate Center's Committee on Globalization and Social Change.

Jarrett Moran is a doctoral candidate in History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, where he is writing a dissertation on the history of the concept of culture in Britain in the nineteenth and twentieth century. He has an MA in Modern European studies from Columbia University and a BA in Ethics, Politics, and Economics from Yale University. He was a Writing Across the Curriculum Fellow at Baruch College and has taught courses on the history of British radicalism and empire at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He is currently a Fellow at the Graduate Center's Committee on Globalization and Social Change.