My primary project as a Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow was daunting to approach but rewarding to undertake: to find and organize a comprehensive checklist of creators with Black, Indigenous, and other marginalized identities represented within the Morgan’s Printed Book collections. As introduced in a previous blog post, Making Visible the Invisible, the checklist was to be created through a survey of the nearly 16,000 unique creators represented in the Printed Books collection, one that spans from the earliest incunables to ephemera from the twentieth century and new artists’ books. This post contains an update on my completion of the checklist project.

Completing the Survey

The survey phase of the project began with looking at the MARC 100 field, the section for the main entry in a machine-readable bibliographic record. The main entry is assigned to the person chiefly responsible for the work, so it serves as the key field of investigation for a checklist of creators. With my set of nearly 16,000 rows of data — a snapshot of the Printed Books collection in Fall 2023 — I began the survey work in OpenRefine. OpenRefine is a free, open source data manipulation tool loved by librarians and data curators for its ability to assist work with large datasets. OpenRefine has the ability to reconcile data with external web databases like Wikidata, making it possible to both mine data from these databases as well as contribute new information back into them.

The survey process can be simplified into three main components: (1) dataset upload and cleanup, (2) reconciliation, and (3) investigation.

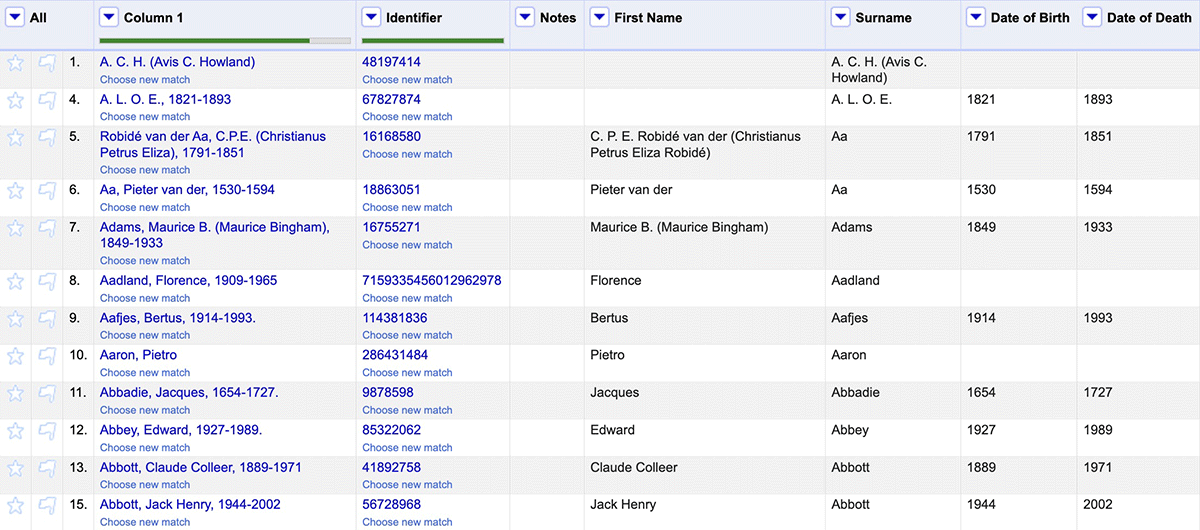

After uploading the raw dataset into OpenRefine, my first task was to standardize the data for reconciliation work. This required some light coding of General Refine Expression Language (GREL) expressions to ensure dates and names were properly formatted. The most important part of this step was splitting the data into distinct columns for first names, surnames, dates of birth, and dates of death. Once the dataset was orderly, I moved to the second step: reconciliation.

My first goal was to connect the creators represented in the Morgan’s collection to authority records, standardized or established forms of representing a person in bibliographic records. I turned first to the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) database. Each authority record on VIAF is associated with a unique ID number. So, by using the names and life dates to reconcile my dataset with VIAF, I was able to link a standard authority record to most of the creators (represented as the “Identifier” column in the screenshot below). Though VIAF is a trusted database for standard forms of names, it does not contain the biographical information I needed to determine eligibility for inclusion in the BIPOC checklist. Therefore, the first reconciliation with VIAF was a setup for the secondary reconciliation with the repository that does have the information: Wikidata. To reconcile my project with Wikidata, I used name and life date information as well as the additional parameter of the unique VIAF IDs. This way, every match I made in Wikidata included the authority records I matched in the previous step.

So, finally, every record either was matched and linked to VIAF and Wikidata or had no match at all. To be precise: of the 15,828 rows of data for which I ran these automated reconciliation processes, 11,435 rows matched successfully and 4,057 rows remained unmatched.

A portion of unmatched values was expected. The Printed Books collection material ranges from well-known philosophers and canonical folios to unique artists’ books and miniatures; I knew there would be some creators not represented in authority records or larger databases that I would have to investigate independently. The last part of my reconciliation process was to parse manually through the unmatched rows.

A large part of the reconciliation was automated; but, as with any automated manipulation or retrieval of information, human intervention and judgement continually proved to be a necessary part of the process.

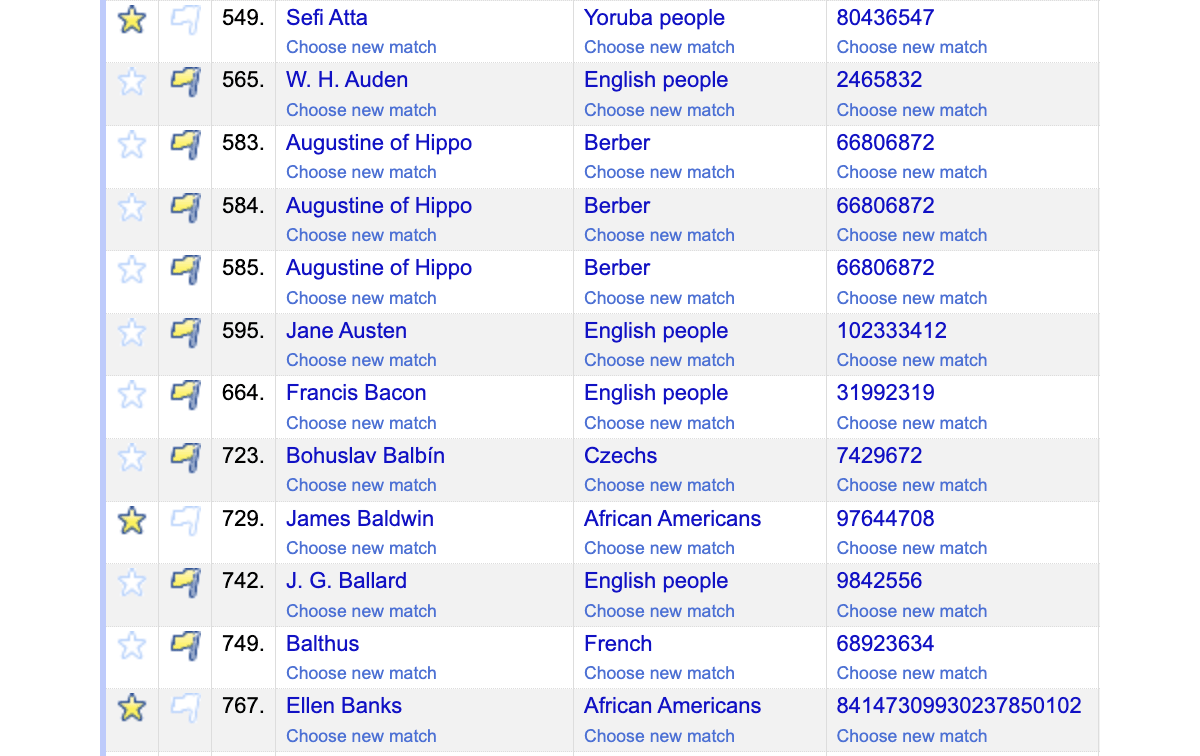

Finally, investigation. My general strategy to sort through records was to flag any row that could be excluded from the BIPOC checklist. For a collection such as this, certain well-known names could be obviously flagged as exclusions. For example, we know that Gutenberg was German, that Aldus Manutius was Italian, that Lewis Carroll was a White Englishman, all of whom can be excluded from a checklist of BIPOC creators. On the flip side, entries were starred for consideration/further investigation or as obvious inclusions.

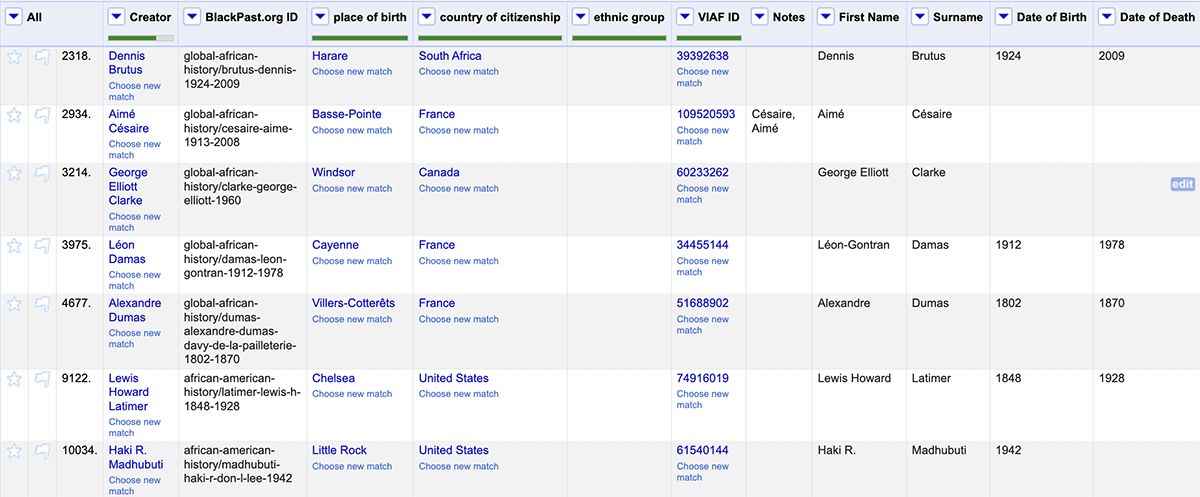

After moving through the unmatched rows, I was still left with a set of 10,000+ matched rows to work with for compiling the checklist. Wikidata includes biographical information helpful for finding racial/ethnic identities and the database has the following properties I considered to be most relevant in my search: ethnic group (P172), place of birth (P19), and country of citizenship (P27). In addition, I found identifiers from other biographical repositories included in Wikidata that could help distinguish BIPOC: African American Visual Artists Database ID (P11271) and BlackPast.org ID (P6723).

Not every Wikidata page has every property. Certain creators like those represented above did not have information on their ethnic group but did have an entry on BlackPast.org, confirming their ethnic identity and therefore their inclusion in the BIPOC checklist. In situations like this where I was able to cross reference multiple authorities and biographical repositories to verify information, I contributed information back into Wikidata to improve entries, always citing the sources.

I took the starred entries and created a new OpenRefine project. The final step of data work before beginning checklist compilation was to remove duplicate names and cross reference how many of these starred MARC 100 field entries appeared in CORSAIR, the Morgan’s online collection catalog. After removing the duplicates and any creators whose records were not in the public catalog, the Printed Books BIPOC checklist was set to include 238 unique individuals and their works.

Conclusion

The Printed Books BIPOC checklist was compiled in Spring 2025. The process of compiling the checklist was something of a meditation for me: moving methodically through the catalog to collect the records for each of the creators I unearthed was incredibly satisfying. As the list grew, my pride for the project grew with it.

As I’ve previously written, all work aimed at increasing visibility of those rendered invisible by Western systems of knowledge—specifically within collecting institutions—will continue to be daunting and time-consuming work. My hope for this project’s legacy is that it will inspire others within more institutions to formulate creative bibliographic methods, illuminating BIPOC creators that may be involuntarily hidden within the data and stay striving to improve access.

It is important to note that this project’s methodology included substantial assumptions: for example, initials were discarded when no further information could be ascertained. Relying on reported information for deceased creators will never be as ethical or accurate as when self-identifications exist. It is also important to note that the project was undertaken with a dataset pulled in early fall of 2023 and that it is not a continually updated document as of this blog post. As such, the checklist represents a moment in time, a snapshot of the collection and a methodology developed early in my fellowship. If time permitted, I would apply this methodology across the collecting departments of the Morgan as a whole and incorporate the results into the public catalog for further access. In the last weeks of my position I am working on creating a scaffolding for the continuation and expansion of the project, optimistic that the momentum will continue.

Sam Mohite (she/her)

Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow

The Morgan Library & Museum