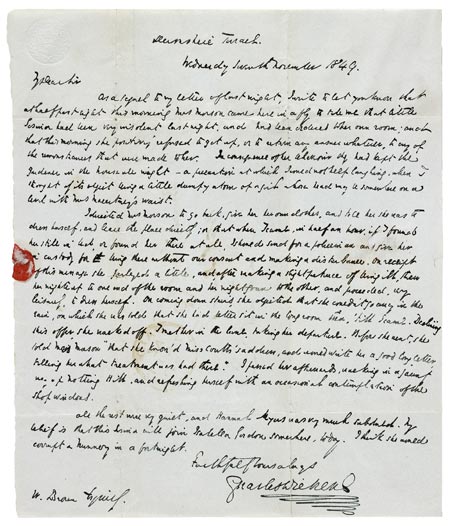

In his 1853 essay "Home for Homeless Women," published in his weekly magazine Household Words, Dickens wrote that the Urania Cottage project hoped to achieve success in thirty to fifty percent of its cases. By 1853 it had exceeded this goal: of the fifty-eight women who had passed through the home, thirty were thought to have flourished after emigration. In the case of the other inmates, three had relapsed during the passage to Australia, seven had left the home during the probationary period, seven had fled, and ten had been discharged. In this letter to William Brown, the physician on the Urania Cottage management committee, Dickens commented that one of the expelled women, named Sesina, "would corrupt a Nunnery in a fortnight."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

My Dear Sir

As a sequel to my letter of last night, I write to let you know that at halfpast eight this morning Mrs. Morson came here in a fly to tell me that little Sesina had been very insolent last night, and had been ordered to her own room; and that this morning she positively refused to get up, or to return any answer whatever, to any of the remonstrances that were made to her. In consequence of her behaviour they had kept the gardener in the house all night—a precaution at which I could not help laughing, when I thought of its object being a little dumpy atom of a girl whose head may be somewhere on a level with Mrs. Macartney's waist.

I directed Mrs. Morson to go back, give her her own clothes, and tell her she was to dress herself, and leave the place directly; or that when I came, in half an hour, if I found her still in bed, or found her there at all, I should send for a policeman and give her in custody for being there without our consent and making a disturbance. On receipt of this message she parleyed a little, and, after making a slight pretence of being ill, th[r]ew her nightcap to one end of the room and her nightgown to the other, and proceeded, very leisurely, to dress herself. On coming down stairs, she objected that she couldn't go away in the rain, on which she was told that she had better sit in the long room then, 'till I came. Declining this offer, she walked off. I met her in the lane, taking her departure. Before she went, she told Mrs. Morson "that she know'd Miss Coutts's address, and would write her a good long letter, telling her what treatment was had there." I passed her afterwards, walking in a jaunty way up Notting Hill, and refreshing herself with an occasional contemplation of the shop windows.

All the rest were very quiet, and Hannah Myers was very much subdued. My belief is that this Sesina will join Isabella Gordon somewhere, today. I think she would corrupt a Nunnery in a fortnight.

Faithfully Yours always

CHARLES DICKENS