Lafcadio Hearn could be a cruel correspondent. One-eyed, diminutive and poor -- and self-described as painfully awkward -- he was nonetheless a hit with certain ladies -- at least fifty, by his own count. One of these ladies, Ellen Freeman, emphatically did not excite reciprocal feelings.

Lafcadio Hearn could be a cruel correspondent. One-eyed, diminutive and poor -- and self-described as painfully awkward -- he was nonetheless a hit with certain ladies -- at least fifty, by his own count. One of these ladies, Ellen Freeman, emphatically did not excite reciprocal feelings.

Hearn’s relationship with Ellen Freeman seems to have formed in 1875, around the time he was fired from the Cincinnati Enquirer following his marriage to Mattie Foley, a former slave. Interracial marriage was illegal at the time, and it scandalized Hearn's circle. This was not the only time he shocked Cincinnati -- as a journalist at the Enquirer and later at the Commercial, Hearn explored the underbelly and margins of society in sensational articles. Reporting from crime scenes, Hearn viscerally described sticking his fingers into a dead man’s brain, slipping on gore, and even drinking blood from abattoirs. He was something of a sensation himself, and caught the eye of the refined and wealthy housewife Ellen Freeman, who was some years older than him. It is clear from the surviving correspondence that she pursued him but that he was not interested. His letters are consistently polite and thankful for frequent gifts of books and flowers, but he remains formal and somewhat standoffish, frequently alluding to his social anxiety and the need to “wear masks in this great Carnival of mummery of life.”

Their relationship came to an abrupt end the following year, possibly as the result of a photograph of her in a low-cut dress. At the very least, his response -- which is one of the most spiteful letters I’ve ever come across -- leaves little to the imagination about his feelings for her.

Transcription follows.

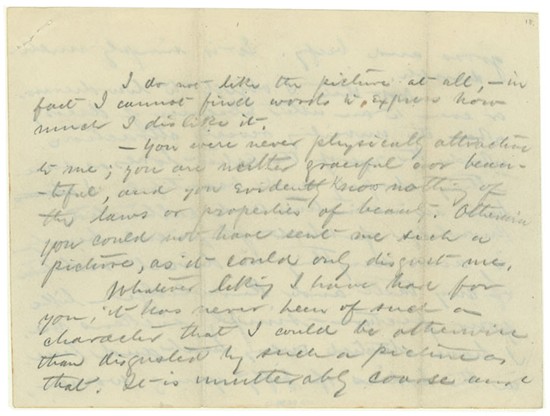

page 1 recto

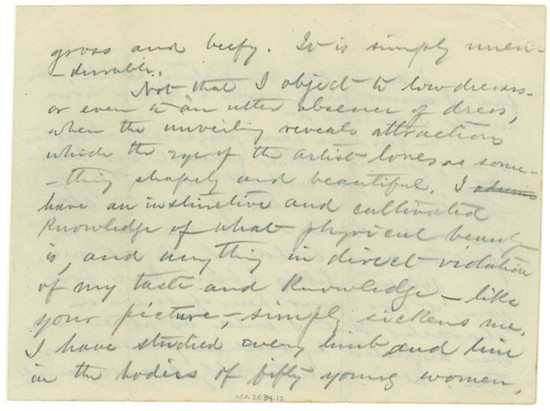

page 1 verso

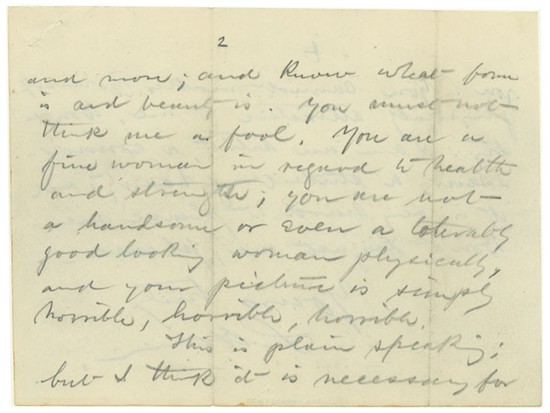

page 2 recto

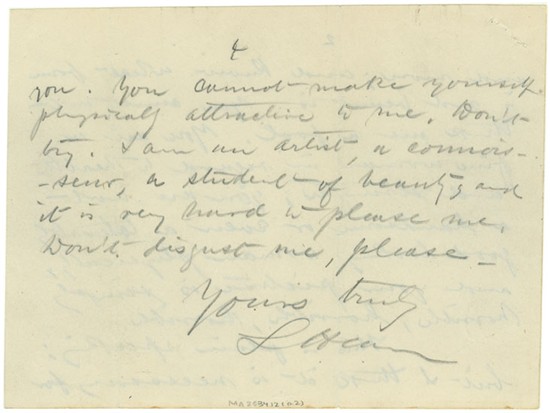

page 2 verso

It reads:

I do not like the picture at all, -- in fact I cannot find words to express how much I dislike it.

You were never physically attractive to me; you are neither graceful nor beautiful, and you evidently know nothing of the laws or properties of beauty. Otherwise you could not have sent me such a picture, as it could only disgust me.

Whatever liking I have had for you, it has never been of such a character that I could be otherwise than disgusted by such a picture as that. It is unutterably coarse and gross and beefy. It is simply unendurable.

Not that I object to low dresses -- or even to an utter absence of dress, when the unveiling reveals attractions which the eye of the artist loves as something shapely and beautiful. I have an instinctive and cultivated knowledge of what physical beauty is, and anything in direct violation of my taste and knowledge -- like your picture, -- simply sickens me. I have studied every limb and line in the bodies of fifty young women, and more; and know what form is and beauty is. You must not think me a fool. You are a fine woman in regard to health and strength; you are not a handsome or even a tolerably good looking woman physically, and your picture is simply horrible, horrible, horrible.

This is plain speaking; but I think it is necessary for you. You cannot make yourself physically attractive to me. Don’t try. I am an artist, a connoisseur, a student of beauty, and it is very hard to please me. Don’t disgust me, please --

Yours truly,

L. Hearn.

A few things about this letter strike me. What did Ellen Freeman look like? This elusive woman -- and her no doubt striking visage -- is lost to us. And how on earth has this letter not only survived, but been intentionally preserved? Hastily scrawled on two thin scraps of paper with a dull pencil, it is the type of missive that you might imagine to be dissolved by tears, crumpled in rage, or thrown into the fire. But Ellen Freeman saved it, and what’s more, gave it back to Hearn when he asked for the return of his letters. Hearn then preserved it for the next dozen years, while he was chronicling the denizens of New Orleans and possibly living with a Voodoo priestess.

Eventually, Hearn gave the whole stack of his correspondence with Ellen Freeman to his friend Henry Watkin to do with them whatever he thought best. Not surprisingly, this letter was not published in Hearn's selected correspondence.

For more information about The Morgan's collection of Lafcadio Hearn letters, click here.

The Leon Levy Foundation is generously underwriting a major project to upgrade catalog records for the Morgan's collection of literary and historical manuscripts. The project is the most substantive effort to date to improve primary research information on a portion of this large and highly important collection.