One Hundred Years of James Joyce's Ulysses

“The important thing is not what we write, but how we write . . . the modern writer must be an adventurer above all, willing to take every risk, and be prepared to founder in his effort. . . . In other words we must write dangerously.”

—James Joyce, from Arthur Power's Conversations with James Joyce

One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” is made possible by The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, the Government of Ireland, the Lucy Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund, and the Drue Heinz Exhibitions and Programs Fund. Additional support is provided by the Themis Anastasia Brown Fund and the Dedalus Foundation.

Overview

Introduction

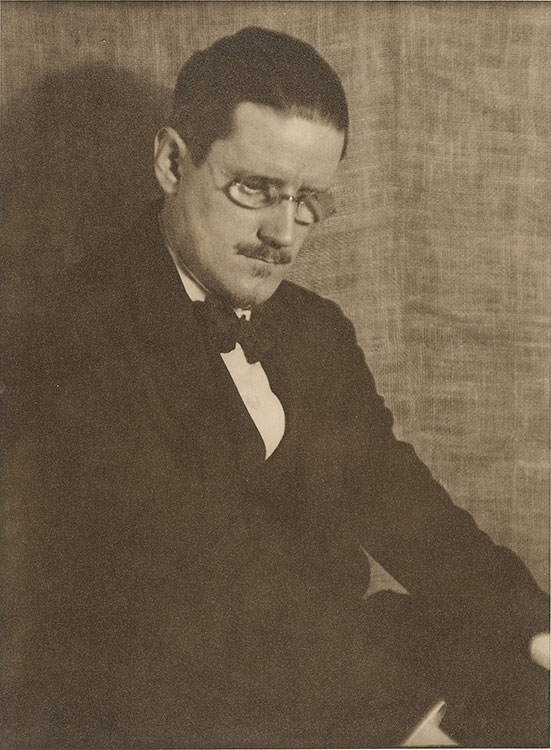

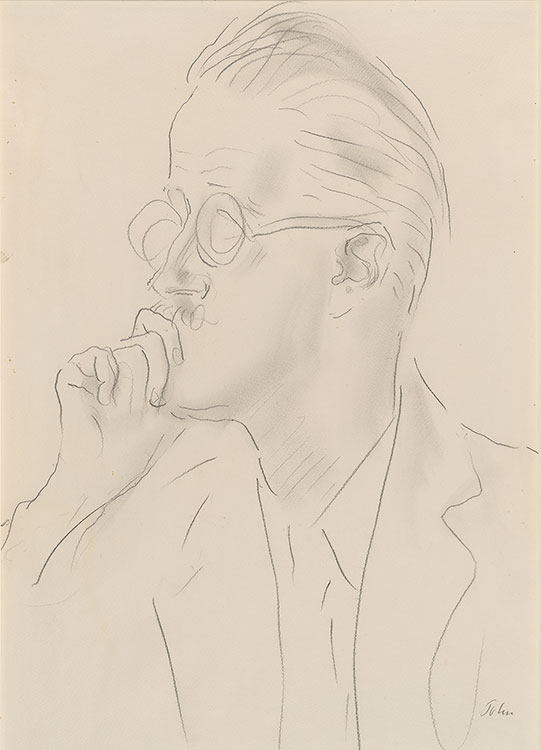

Berenice Abbott (1898–1991)

James Joyce, 1928

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; 2018.20

© Berenice Abbott via Getty Images

Hello. I’m Colin B. Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library and Museum, and I am delighted to welcome you to One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Set on one day, June 16 1904, James Joyce’s Ulysses follows the young poet Stephen Dedalus and the unlikely hero Leopold Bloom as they journey through Dublin. Ulysses is the preeminent modernist novel of the twentieth century, a literary masterpiece of epic proportions with daring innovations in subject matter, style, and structure. It expanded the limits of language and genre—and not without controversy. Censored and banned in America and England for obscenity, its publication in Paris a century ago was the catalyst for new legal standards of artistic freedom.

In the gallery you will explore Joyce’s trajectory from lyric poet to modernist genius, encountering the family who shaped him as a man and writer; key figures in his career including Sylvia Beach, Harriet Shaw Weaver, and Ezra Pound; and artists and authors who responded to the novel, such as Virginia Woolf, Henri Matisse, and Ralph Ellison. At the exhibition’s heart is Joyce’s profound imagination as he crafted Ulysses, explored in manuscripts, plans, and proofs, with major loans from some of world’s richest Joyce collections.

This presentation celebrates a significant gift to the Morgan by Sean and Mary Kelly, who over several decades accumulated one of the foremost Joyce collections in private hands. They hoped that their gift would help others appreciate the novel—that we would use it to guide readers through the intricacies of the text and show them its pleasures and rewards.

As you move through the gallery, look for the audio symbols to hear guest curator and acclaimed novelist Colm Tóibín speak about the people and places that inspired Ulysses.

Thank you for joining us at the Morgan. We hope you enjoy your visit.

Joyce's Youth

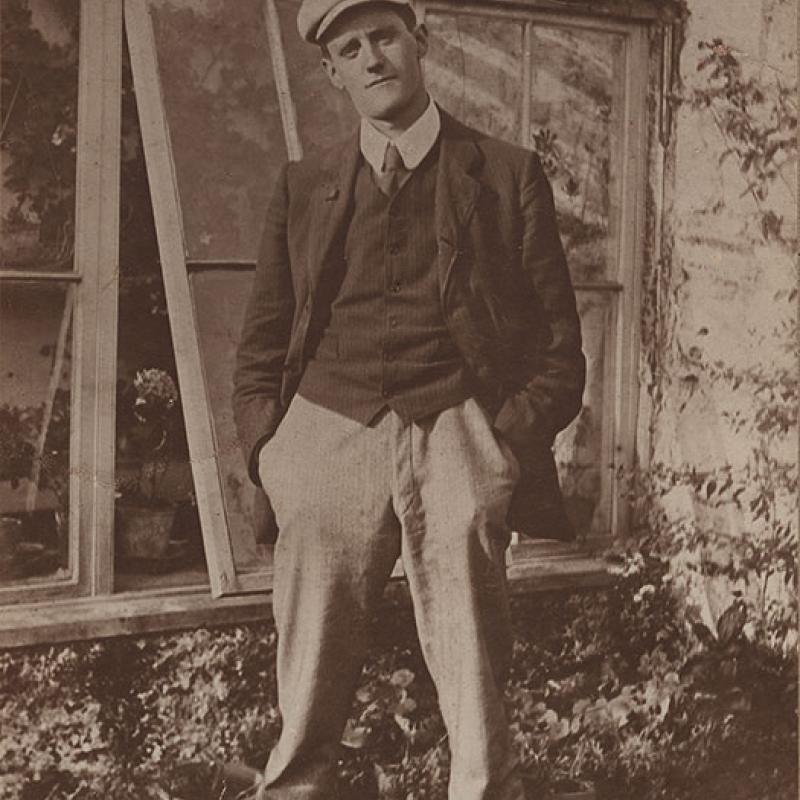

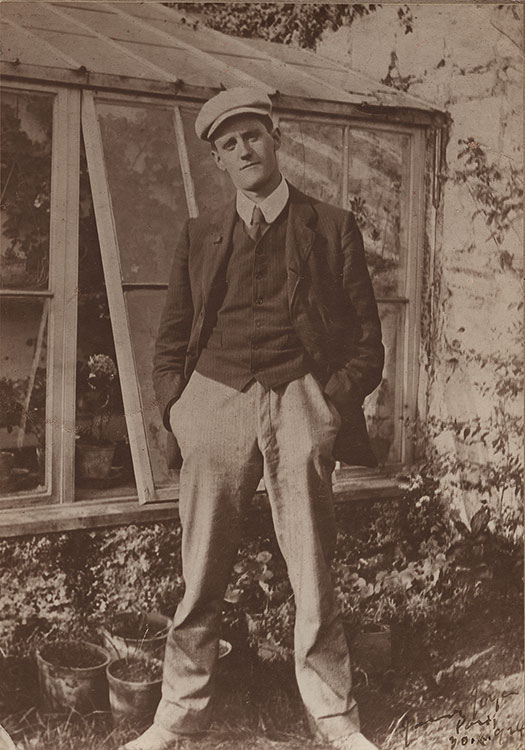

Constantine P. Curran (1886–1972)

James Joyce, Dublin, 1904

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

James Joyce was born in Dublin in 1882. He was the eldest of a large family, a family at the time he was born was a prosperous family. His father had a job and owned property and got rents from the property. But slowly, his father began to mortgage the properties. His father was a drinker, his father was a waster, and so the family declined and often moved house with bailiffs often in pursuit. And this was his childhood. The city too, the city of Dublin, where he was brought up, was not a prosperous city, it was a city also in decline. There was really no manufacturing base, and there were many living in slums without proper sanitation. And Dublin famously had the largest Red Light District in Europe. And in his book Ulysses, Joyce, James Joyce, would portray these surroundings in detail, he said to a friend that it were so complete, that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth, it could be reconstructed out of my book.

In University College Dublin, Joyce developed literary interests, but he disliked the prevailing insularity and cultural nationalism, which was growing in Ireland. And this really was part of his decision to leave Ireland in 1904. And a few months before he left the city, he met Nora Barnacle who would become his companion for life. And the first date they had was on the 16th of June 1904, and that was the day on which he said his novel, Ulysses.

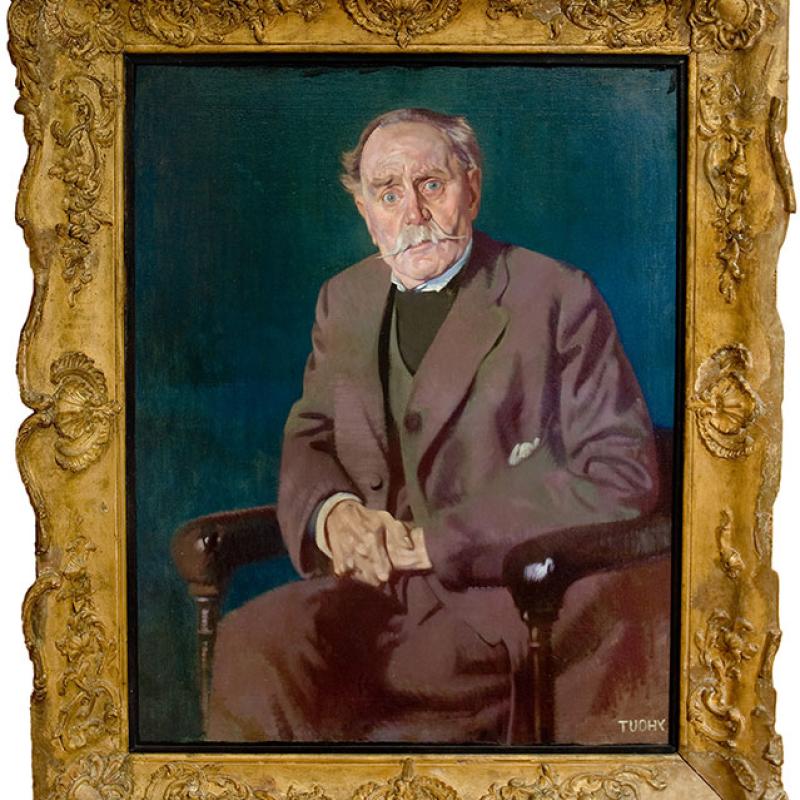

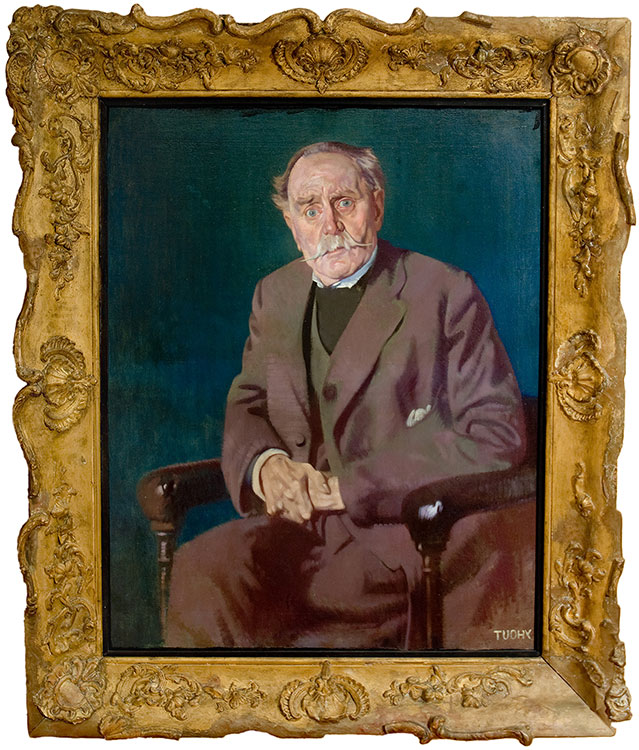

Joyce's father, John Stanislaus Joyce

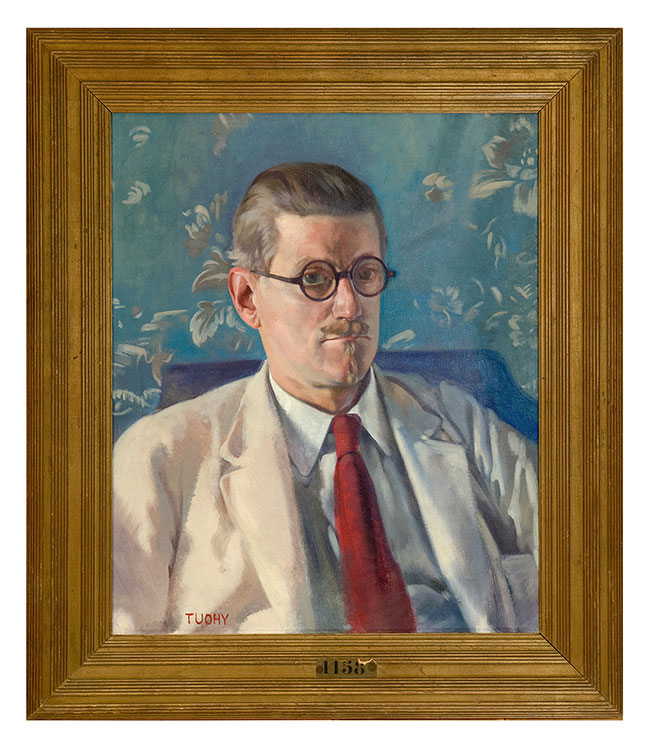

Patrick Tuohy (1894–1930)

Portrait of John Stanislaus Joyce, ca. 1923–24

Oil on canvas

The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

We cannot overestimate the importance of James Joyce's father in the making of the novel Ulysses. Joyce wrote about him, “I got from him his portraits, a waistcoat, a good tenor voice, and an extravagant licentious disposition.” In the novel Ulysses, Simon Dedalus is a version of John Stanislaus Joyce, James Joyce's father. And obviously the father was a very bad provider for his family, but what Joyce did in the novel was he showed him as a figure on the streets, as a popular man. He was leaving his daughters penniless, but he was also witty. He was good company and of course, he had a beautiful tenor voice that soars especially in the Sirens episode of the novel. About his father's influence on the novel Ulysses, Joyce told a friend, “The humor of Ulysses is his. Its people are his friends. The book is his spittin’ image.”

Joyce's mother, May Murray Joyce

Unknown photographer

James Joyce with his mother, father, and maternal grandfather, 1888

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Music was really important in the Joyce family. Joyce's mother, May Murray, she came from a musical family, and a friend of her sons remembered her as a frail, sad faced, and gentle lady, whose skill at music suggested a sensitive, artistic temperament. She, from an early age, took piano and voice lessons at school, run by two of her mother sisters beside the River Liffey. And of course, this house became the house of the story, The Dead, and these women became the women who give the party in The Dead. In Ulysses, May appears as, in the Cersei episode, as the ghost of May Goulding. Between 1881, when she was twenty-two, and 1893, May Murray had ten children and three miscarriages. She died of cancer at the age of forty-four. Joyce was summoned back from Paris to her deathbed, an event that would haunt the early episodes of Ulysses.

University College Dublin

Unknown photographer

James Joyce in his Royal University graduation gown , 1902

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

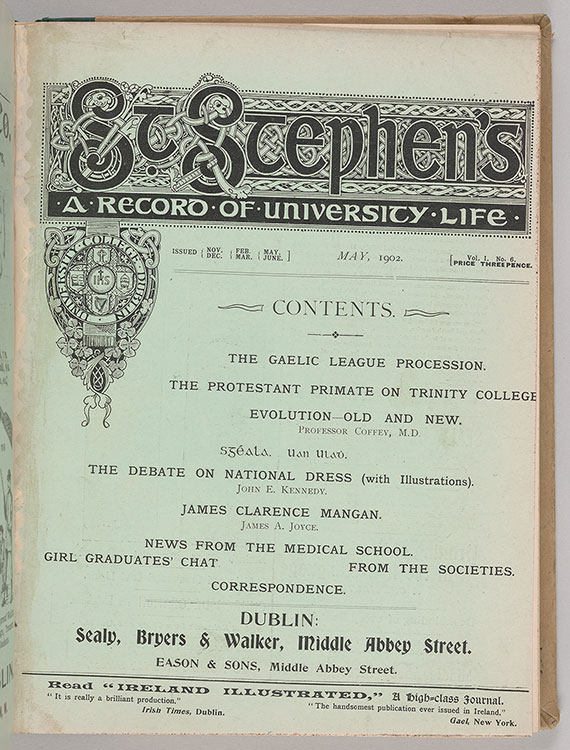

"Planetary Music"

Joyce’s classmates started the magazine St. Stephen’s during his senior year at University College, then part of the Royal University of Ireland. Though independently run, the publication was at the mercy of administrative oversight. Joyce’s submissions of poems, stories, and essays were rejected by the editors or censored by school authorities, with the exception of a piece on the Irish poet James Clarence Mangan (1803–1849). In the essay, Joyce writes, “The philosophic mind inclines always to an elaborate life—the life of Goethe or of Leonardo da Vinci; but the life of the poet is intense—the life of Blake or of Dante—taking into its centre the life that surrounds it and flinging it abroad again amid planetary music.”

St. Stephen’s: A Record of University Life 1, no. 6 (May 1902)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mr. And Mrs. Robert D. Graff, 1975; PML 65946

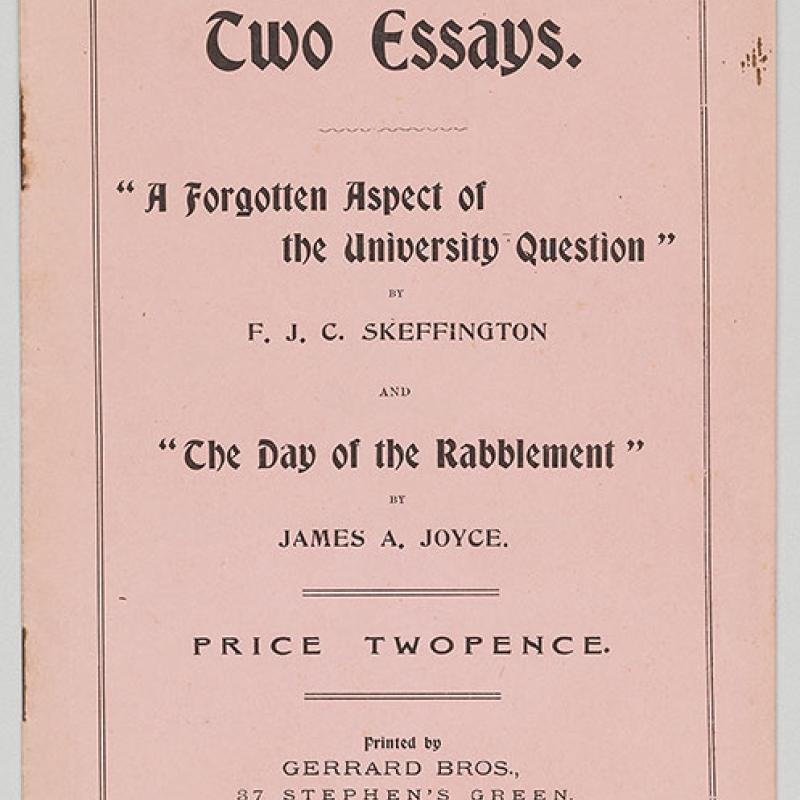

The Day of the Rabblement

Joyce became interested in contemporary drama while at university. He praised naturalist plays for their acceptance of life “as we see it,” and people “as we meet them.” The Irish Literary Theatre, spearheaded by the writers W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, was by then exclusively devoted to Irish plays. Joyce’s essay “The Day of the Rabblement” disparaged the project for its lack of cosmopolitanism. One pronouncement points to his life’s trajectory: “A nation which never advanced so far as a miracle-play affords no literary model to the artist, and he must look abroad.” When his school’s magazine refused to print the essay, Joyce and Francis Skeffington, whose submission had also been rejected, self-published this pamphlet.

F. J. C. Skeffington (1878–1916) and James Joyce (1882–1941)

Two Essays: “A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question” and “The Day of the Rabblement”

Dublin: [printed for the authors by] Gerrard Bros., 1901

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197770

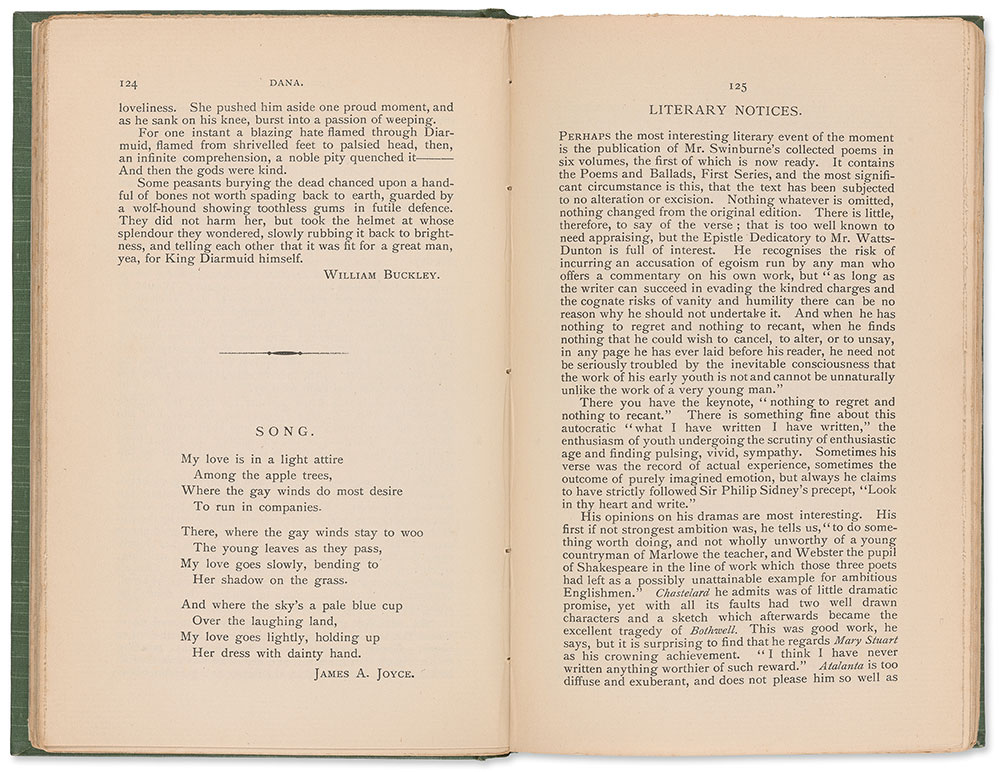

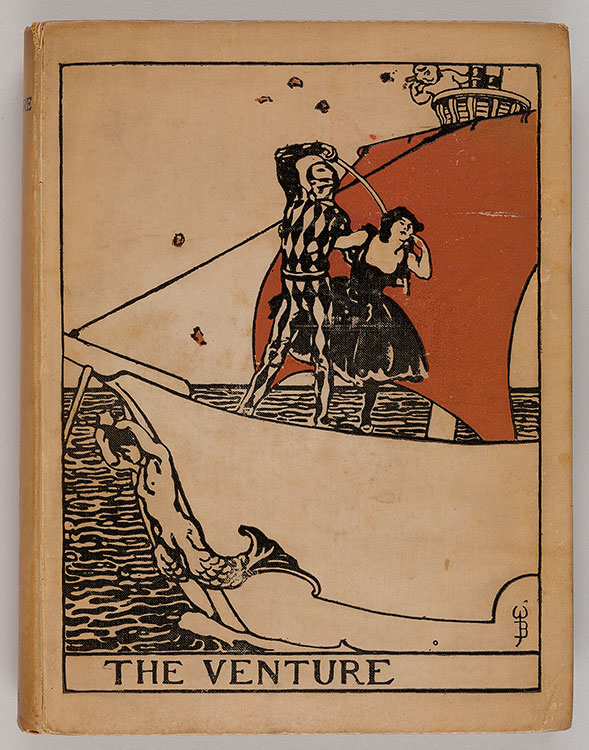

A Young Poet

In the years immediately following Joyce’s graduation, his poems began to appear in English and Irish publications, such as the Venture and Dana. Joyce had hoped that Dana would instead accept a piece of prose titled “A Portrait of the Artist.” He reportedly cornered the magazine’s coeditor John Eglinton at his day job at the National Library and stood by while Eglinton read the piece. Eglinton recollected that he passed it back to Joyce, saying it was “incomprehensible.” According to Joyce, the Dana editors had admired the style but could not abide the references to sex. Both Dana and a supercilious librarian named John Eglinton appear in Ulysses.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

“Song”

In Dana: An Irish Magazine of Independent Thought 1, no. 4 (August 1904)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197772

The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature

Cover illustration by Walter Bayes (1869–1956)

London: John Baillie, 1905 [i.e., 1904]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197773

© The Estate of James Joyce.

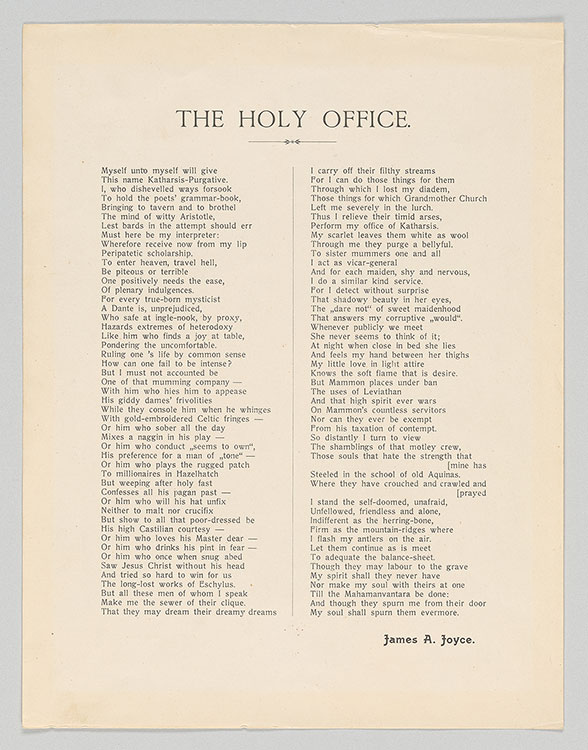

The Holy Office

Joyce composed The Holy Office shortly before he left Dublin in fall 1904. Titled after the Catholic organization that ruled on matters of heresy, the poem attacks the Irish literati— including several writers who encouraged Joyce in his career, such as W. B. Yeats and George Moore. When nobody would print The Holy Office, Joyce self-published it as a broadside, but he could not afford to pick it up before leaving Ireland. The printers eventually destroyed the sheets. After settling in Trieste in 1905, Joyce printed one hundred copies at the city’s most famous stationer. He sent half the edition to his brother Stanislaus in Dublin, instructing him to distribute the broadside to specific friends and writers, some of whom Joyce targeted in the poem.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

The Holy Office

[Trieste: printed for the author by L. Smolars, 1905]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197771

© The Estate of James Joyce.

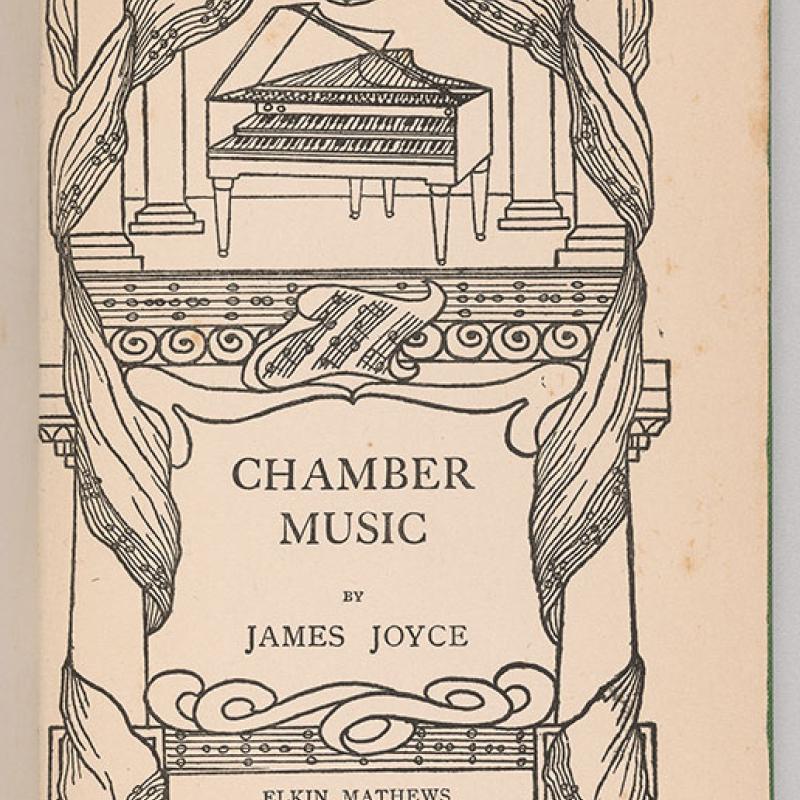

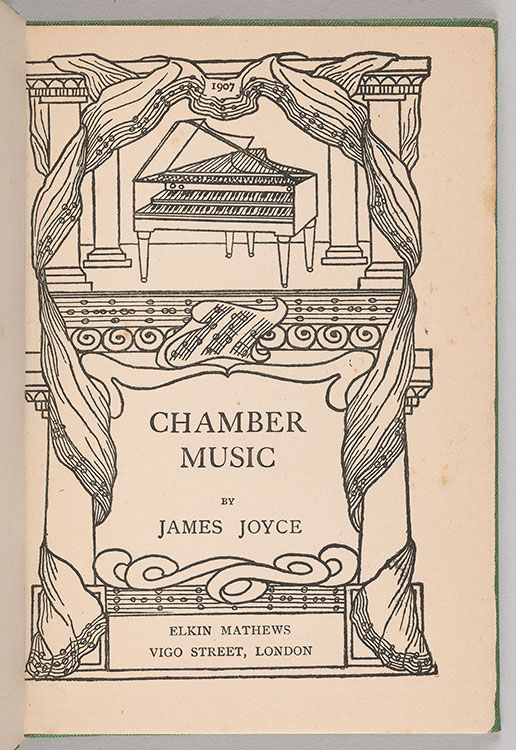

Chamber Music

There is a young boy named Joyce, who may do something.

He is proud as Lucifer and writes verses perfect in their technique.

—George Russell

The influential critic and poet Arthur Symons met Joyce in 1902. Like other well-known writers, such as W. B. Yeats and George Russell, Symons praised Joyce’s poetry for its beauty and audacity. Eager to assist, Symons sent Joyce’s Chamber Music manuscript to many publishers, though all of them turned it down. By the time Elkin Mathews agreed to print the book, Joyce was more invested in writing fiction. His brother Stanislaus sequenced the poems, though Joyce later claimed he had devised the order himself as a carefully constructed piece of music.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Chamber Music

London: Elkin Matthews, 1907

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197774-75

© The Estate of James Joyce.

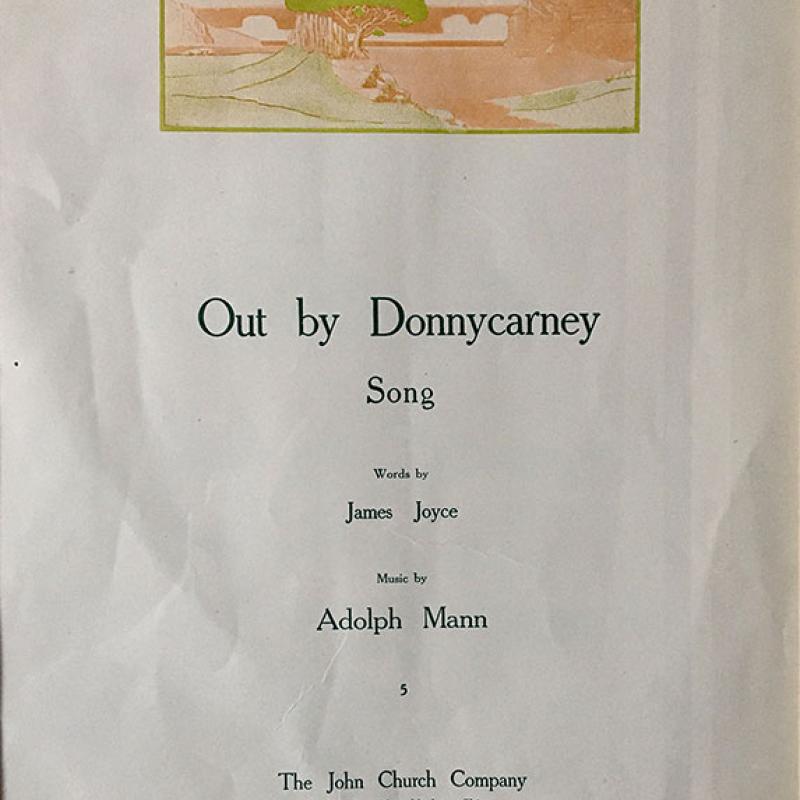

Out by Donnycarney

Adolph Mann (1874–1941)

Out by Donnycarney: Song, Words by James Joyce

Cincinnati: John Church, 1910

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2018; PML 197954

Joyce's letter to a composer about Dubliners

This letter to Adolph Mann (1874–1941)—one of many composers to set Joyce’s poems to music—dates from 1910. Joyce’s musicality (he had pondered a career as a singer) is reflected in his brief, though nuanced, evaluation of Mann’s composition. As the letter indicates, Joyce is much more interested in the proofs he is revising for the imminent publication of Dubliners, a book of short stories. His optimism about Dubliners would soon vanish. The process of publishing it would be drawn out for four more years, primarily because Joyce would not consent to editors’ and printers’ demands for changes.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Letter to Adolph Mann

24 June 1910

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2018; MA 22859

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Gas from a Burner

Joyce was visiting Ireland when a second publisher reneged on their agreement to bring out Dubliners. The printer pulped the book, anticipating charges of libel and obscenity. Joyce responded with this satiric poem, which he later self-published as a broadside. The narrator, a printer-publisher, traces his shifting reactions to Joyce’s short stories: from initial neutrality to recoil upon seeing the work typeset, followed by patriotic self-righteousness and fear for his soul if he were to print actual placenames in Dublin. The narrator decides to burn the edition and, as a penance, to have his buttocks anointed with Dubliners’ ashes.

After the book’s destruction, a distraught Joyce had visited his father, whose advice was to “buck up, take back the [manuscript] and find another publisher.” Joyce left Ireland that night and never saw his father or homeland again.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Gas from a Burner

[Trieste: printed for the author, 1912]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197778

© The Estate of James Joyce.

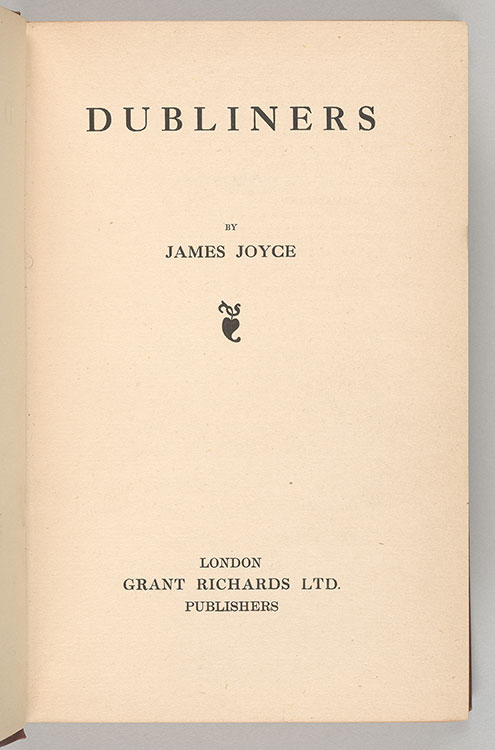

Dubliners

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Dubliners

London: Grant Richards Ltd., 1914

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197779

James Joyce’s first book of fiction was a book of stories called Dubliners. He began to compose the stories in Dublin in 1904 when he was twenty-two and he finished the last one, The Dead in Trieste in 1907. He wrote to a publisher about the style of the book and his ambition for it, “My intention was to write a chapter of the moral history of my country, and I chose Dublin for the scene, because that city seemed to be the center of paralysis. I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness.”

Joyce had very bad luck with publishers, who refused to publish the book for various reasons, including that some of the descriptions were far too frank for the Dublin of the early twentieth century. The book was finally published in June 1914.

Nora Barnacle

Unknown photographer

Nora Barnacle, ca. 1915–1920

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The relationship between James Joyce and Nora Barnacle is a great romance. Nora was born in Galway in the west of Ireland in 1884. One day, on the 10th of June 1904, she bumped into James Joyce on a street in Dublin. They looked at one another, they spoke, and they arranged to meet four days later, outside the childhood home of the writer Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square in Dublin. But Nora did not turn up, so Joyce left her a note at the rooming house where she worked, Finn's Hotel, and he met again on the sixteenth of June, the date on which Ulysses is set. And later, James Joyce would tell his lifetime companion, “You made me a man.”

Joyce and Nora Barnacle left Ireland together in 1904. They had two children, Georgio in 1905 and Lucia in 1907. Though the couple described themselves as husband and wife, in fact, they did not marry until 1931. Joyce used Nora's personality, indeed, and her background in the west of Ireland for the character of Greta Conroy in his story The Dead. But I think perhaps, more importantly, he incorporated her frankness, her sensuality, and indeed, some of her ways of speaking and writing into the figure of Molly Bloom in Ulysses. Nora barnacle died in Zurich in 1951.

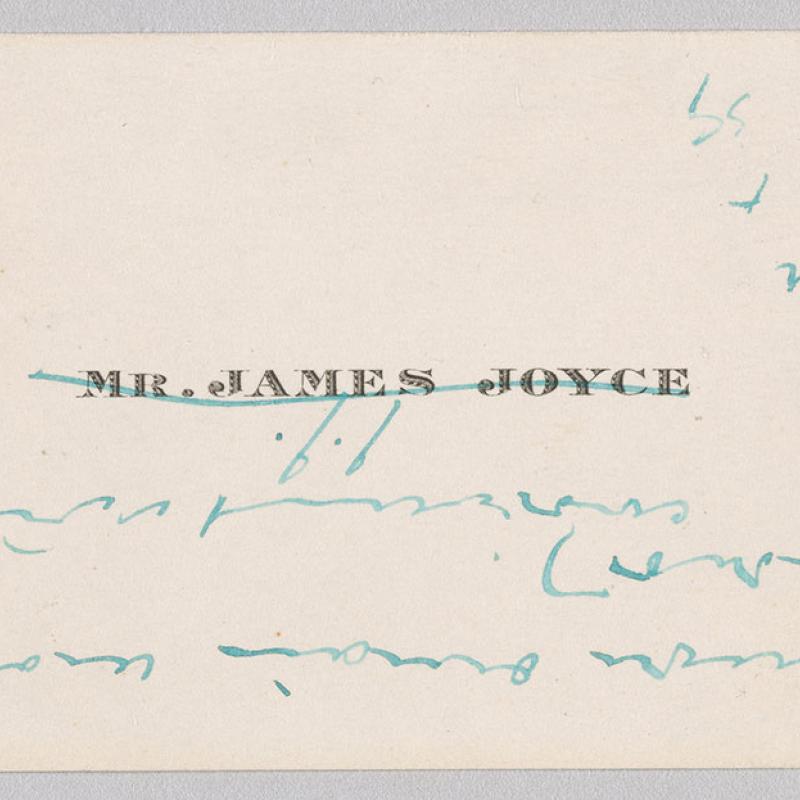

A Letter from Joyce to Nora

Joyce sought to explore every area of human activity in Ulysses. The reader is privy to Leopold Bloom’s thoughts as his mind wanders from subject to subject—and as he masturbates and even farts. Joyce was brought up in a society that was predominantly Catholic and, in its attitudes toward sex, fiercely Victorian and prudish. To write graphically about sex was to break a great taboo, and it was Ulysses’ sexual content that caused the book to be banned in the United States and United Kingdom. In a letter on view to Nora Barnacle, we see Joyce, open about his desires, as daring in his private correspondence as he is in his art.

Frank Budgen (1882–1971)

Portrait of Nora Barnacle, ca. 1919

Oil on board

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The Joyce Family

Unknown photographer

James, Giorgio, Lucia, and Nora Barnacle Joyce, 1924

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The Marriage of James and Nora

Unknown photographer

Nora Barnacle and James Joyce on their way to be married, with Fred Monro, 1931

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

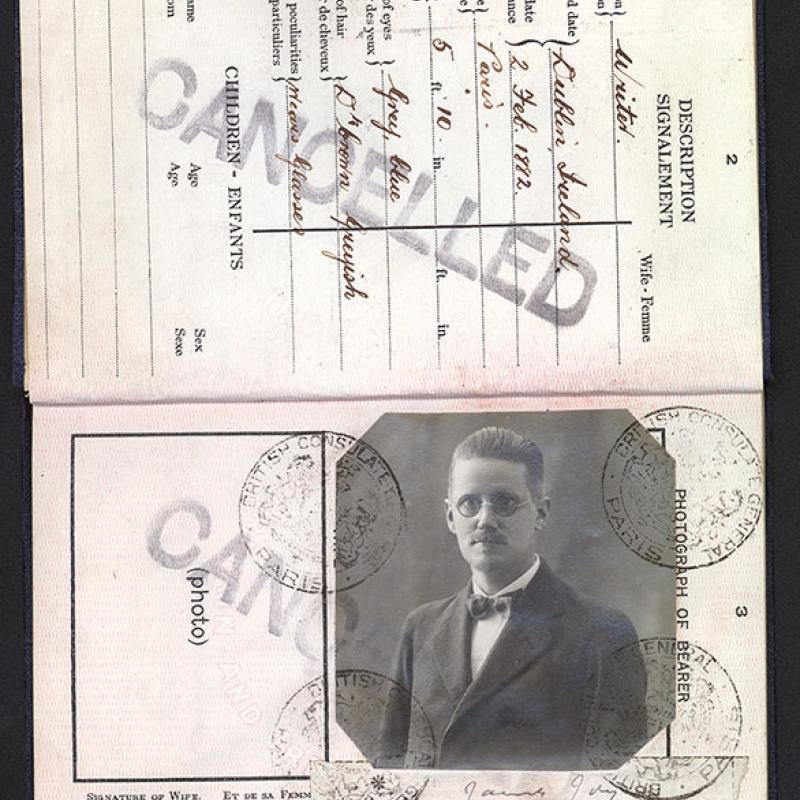

Exile

James Joyce’s British passport, issued 1924

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

In October 1904, James Joyce and his companion Nora Barnacle, they left Ireland on their epic journey to Europe. Joyce planned to make a living, teaching English. Finally they settled in the city of Trieste. During the time there, Joyce published his book of poems Chamber Music, he finished his book Dubliners, he wrote his autobiographical novel Stephen Hero, which he later redrafted as Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. And as the First World War began in 1914, he was writing his play Exiles and beginning work on Ulysses. Trieste was for him an exciting place. It was the main port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He took advantage of its rich cultural life and indeed he was joined by his brother Stanislaus, and we have from Stanislaus’ diaries evidence of their going to the opera every night or going to plays. Trieste was a small city, but unlike Dublin, it was multi ethnic, so to his fascination, he could hear many languages on the streets and as an English teacher, of course, he got to know a cross section of the city's inhabitants. He was passionately engaged, of course, with Ireland's fraught relationship with the British Empire and so, therefore, he understood the fierce arguments going on in Trieste then about the future of Italy, and the future of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

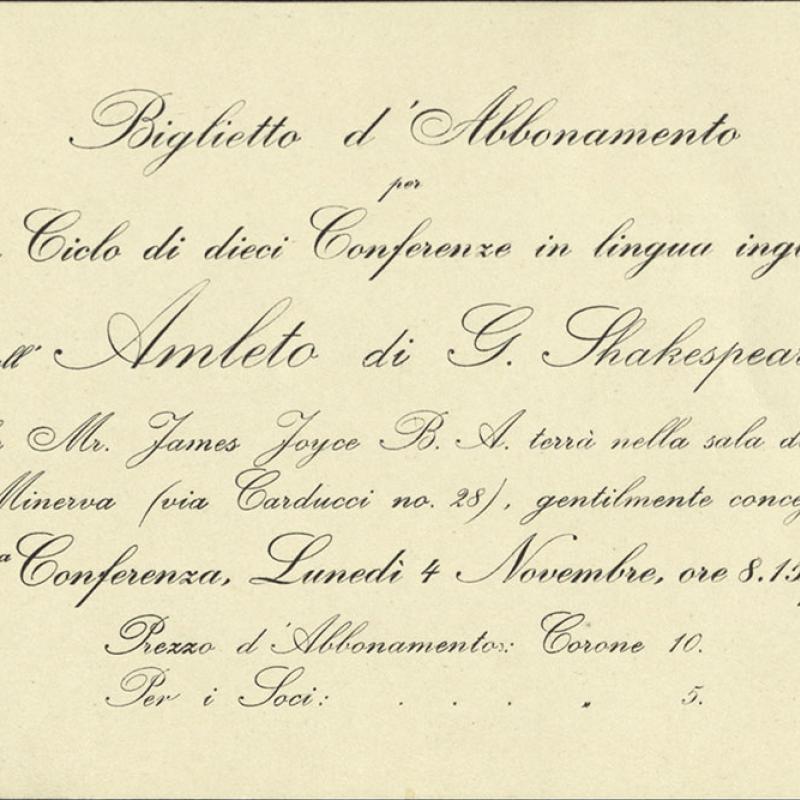

Joyce's Lectures on Hamlet

Subscription ticket for James Joyce’s lectures on Hamlet, Società di Minerva, Trieste,

November 1912–February 1913

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The structure of James Joyce's Ulysses, is based on Homer's The Odyssey and there are many correspondences between the two works. But another text, which is really important for Ulysses, is Shakespeare's Hamlet. In the novel, the young Stephen Dedalus gives a sort of an impromptu lecture in the National Library on Hamlet. And in fact, when Joyce was living in Trieste, he himself gave a number of lectures in the city about Hamlet. And in those lectures, he began to tease out ideas and images that would later appear often transformed in Ulysses.

A Model for Leopold Bloom

When Joyce taught English at the Berlitz School in Trieste, one of his pupils was an older Jewish industrialist named Ettore Schmitz, who published under the name Italo Svevo. He became one of Joyce’s closest friends in the city and a source for the main character in Ulysses, Leopold Bloom. Svevo, like Bloom, married a Gentile and had what Joyce’s biographer Richard Ellmann called “an amiably ironic view of life.” Joyce encouraged his student to persevere as a writer. Svevo’s best-known book, La coscienza di Zeno (Zeno’s Conscience), was published one year after Ulysses. In a 1927 lecture, translated later by Joyce’s brother, Svevo describes the feeling among Triestines “that [Joyce] belonged in a certain sense to us.”

Front and back cover of Italo Svevo (1861–1928), James Joyce: A Lecture Delivered in Milan in 1927 by His Friend. Translated by Stanislaus Joyce (New York: New Directions, 1950)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197843

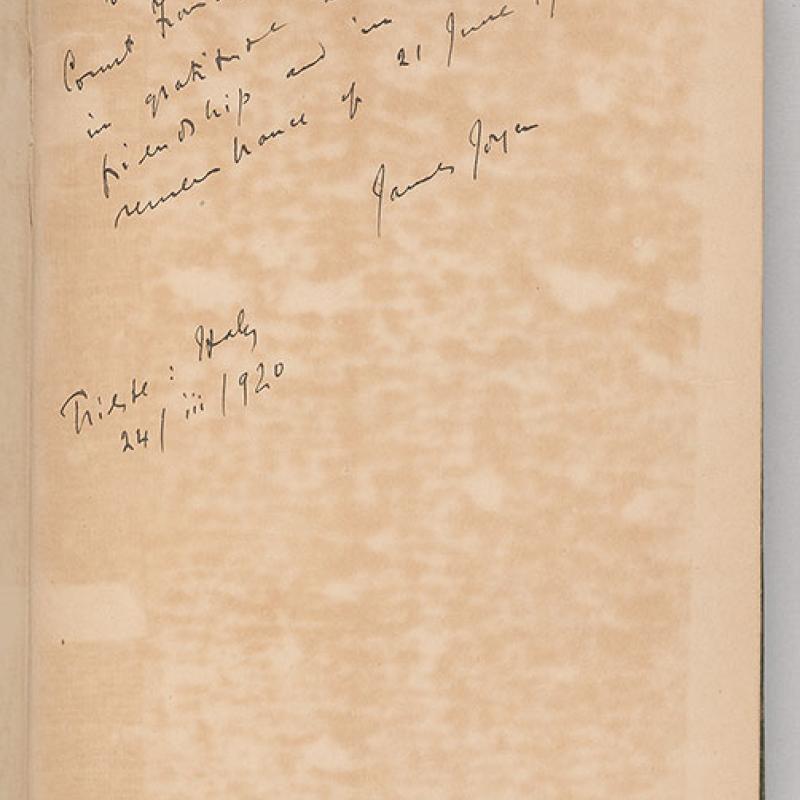

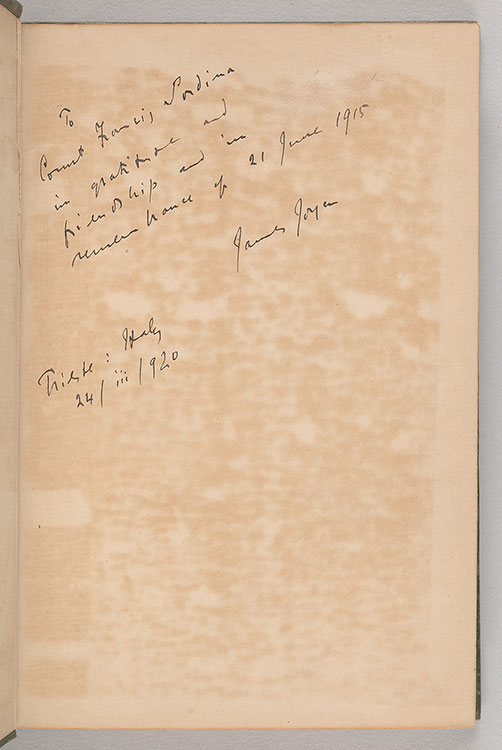

Greeks Bring Good Luck

Joyce was superstitious about Greece, believing that its citizens (“from noblemen down to onionsellers”) brought him good fortune—so much so, that it would affect Ulysses' book design. Count Francesco Sordina, a Greek aristocrat living in Trieste, enrolled in one of Joyce’s first English classes, elevating his instructor’s standing at the school by recommending the course to other wealthy Triestines. Their friendship endured. After World War One began, Sordina and another nobleman helped Joyce and his family emigrate to Zurich. The author memorialized the day they entered Switzerland by inscribing this book to Sordina: “in gratitude and friendship and in remembrance of 21 June 1915.”

Inscription from James Joyce to Count Francesco Sordina

In, James Joyce (1882–1941), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (London: Egoist Ltd., 1917 [i.e., 1918]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197782

© The Estate of James Joyce.

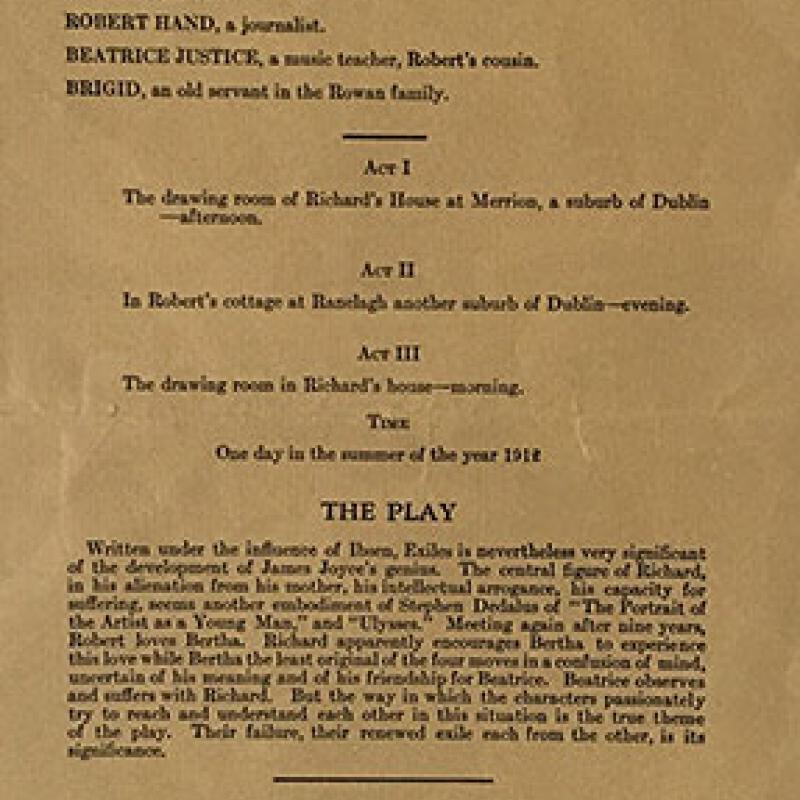

Exiles: A Play in Three Acts

Sexual jealousy and infidelity, themes dramatized in Ulysses, are also portrayed in the play Exiles, Joyce’s least successful work. For years he tried to interest theatrical companies in England, Ireland, and America; there were no takers until August 1919, when Exiles was staged in a German translation in Munich. Joyce summed up the world premiere: “Complete fiasco. Row in theatre. Play withdrawn. Author invited but not present. . . . Thank God.” Exiles was finally performed in English in 1925, at New York’s Neighborhood Playhouse.

This rare broadside program relates to an amateur production mounted the following year by notable figures in the burgeoning gay rights and Little Theatre movements in Boston and Provincetown: Prescott Townsend (1894–1973) and Catherine Sargent Huntington (1887–1987), the play's director. The Boston Stage Society’s repertoire in the 1920s featured European plays by Strindberg, Chekhov, Jean Cocteau, and more obscure modern dramatists. Joyce may not have been aware of this production, nor was he likely compensated.

“Exiles” by James Joyce, Presented by the Boston Stage Society, Saturday, April 3rd–Saturday, April 10th

[Boston: Boston Stage Society, 1926]

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2021; PML 198668

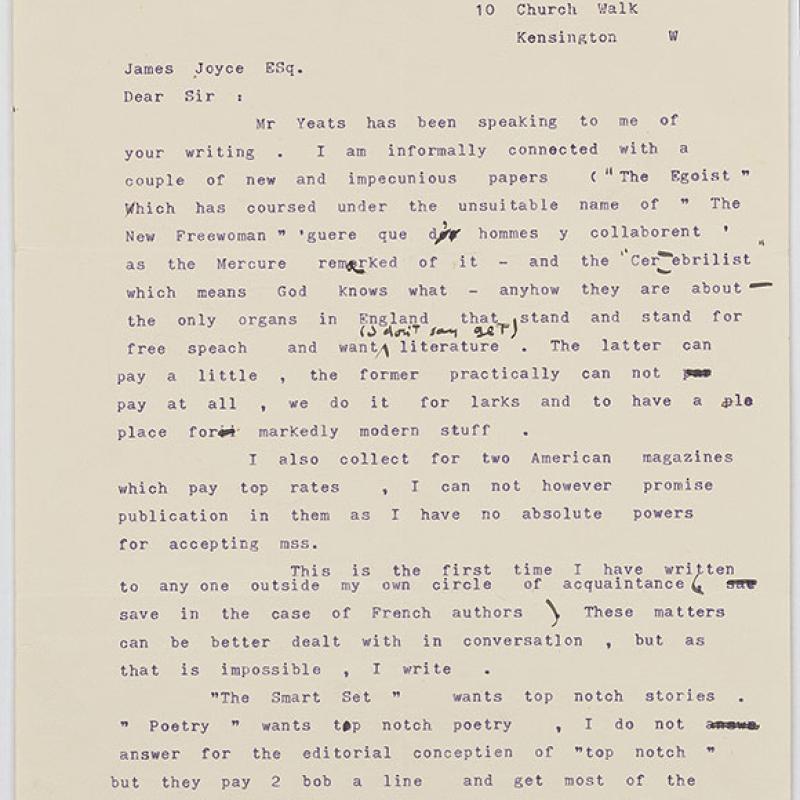

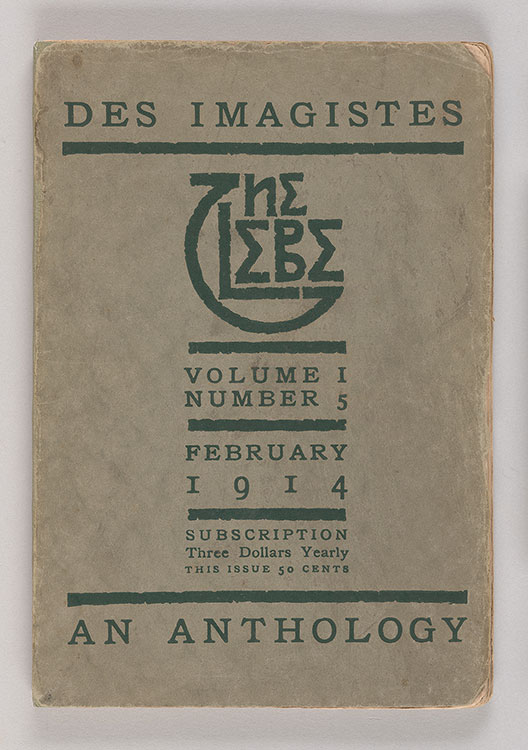

Ezra Pound Introduces Himself

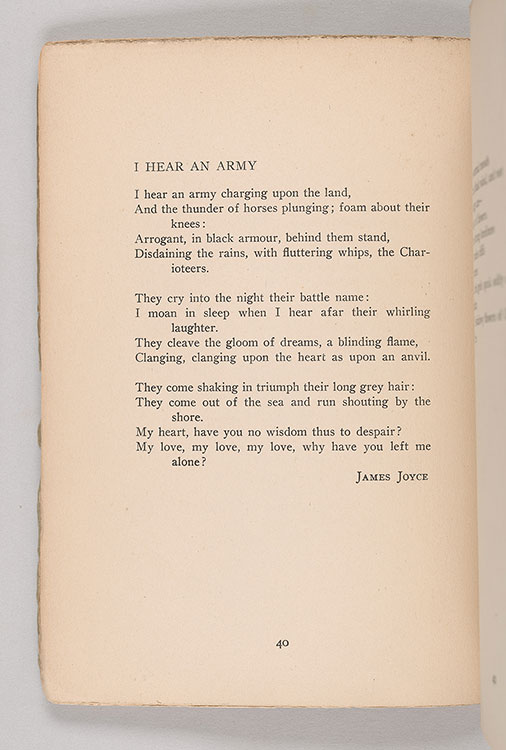

Joyce’s 1903 poem “I Hear an Army” was admired by Irish writer W. B. Yeats, who called it “a technical and emotional masterpiece.” When the poem reappeared in an anthology a decade later, Yeats recommended it to the American poet Ezra Pound. Shown here is Pound’s letter of introduction to Joyce. Before Joyce could answer, Pound wrote again to ask if he could include “I Hear an Army” in the first anthology of Imagist poetry, initially published as a special issue of the American magazine the Glebe. His compliments emboldened Joyce to send Pound Dubliners and the first chapter of his new novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Within a month, thanks to Pound, the serialization of Portrait commenced in the English literary magazine The Egoist.

Ezra Pound (1885–1972)

Letter to James Joyce, 15 December 1913

James Joyce Collection, #4609, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

From POUND/JOYCE: Letters & Essays, copyright ©1967 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

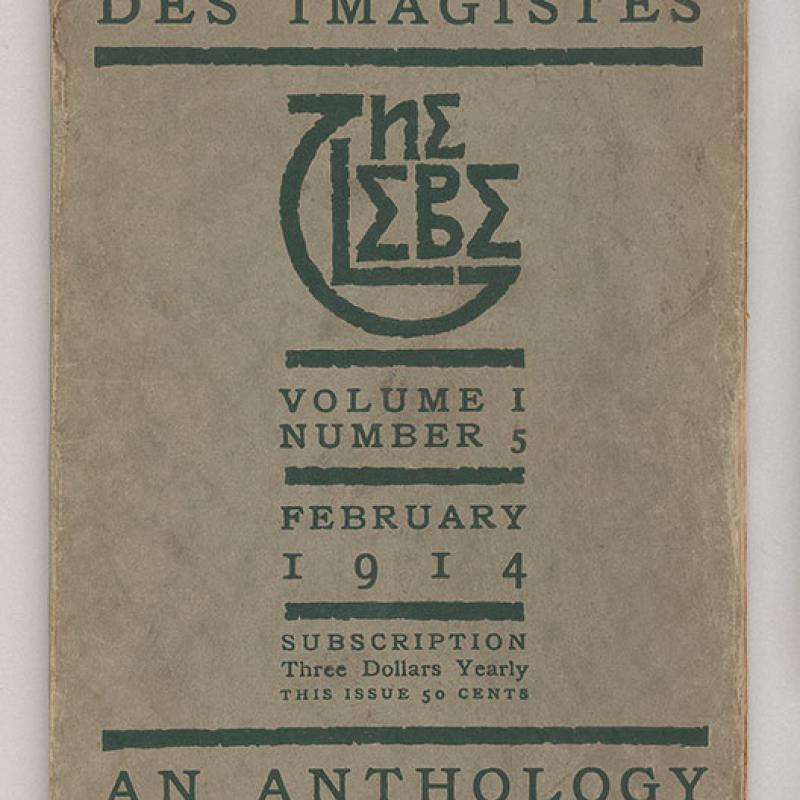

I Hear an Army

James Joyce (1882–1941)

“I Hear an Army”

In, “Des Imagistes: An Anthology.” Edited by Ezra Pound. Special issue, Glebe 1, no. 5 (February 1914)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197777

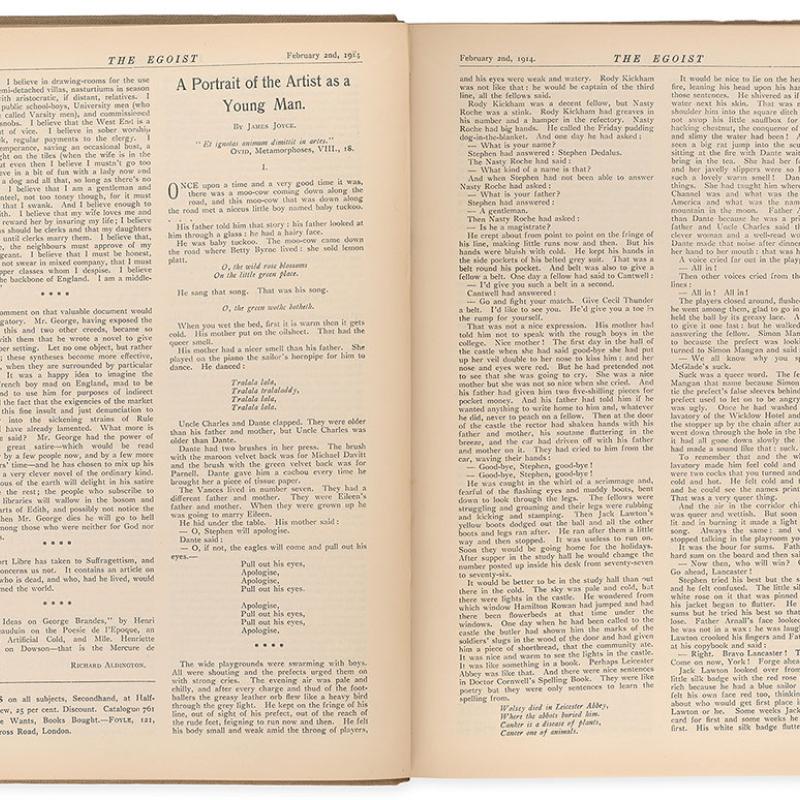

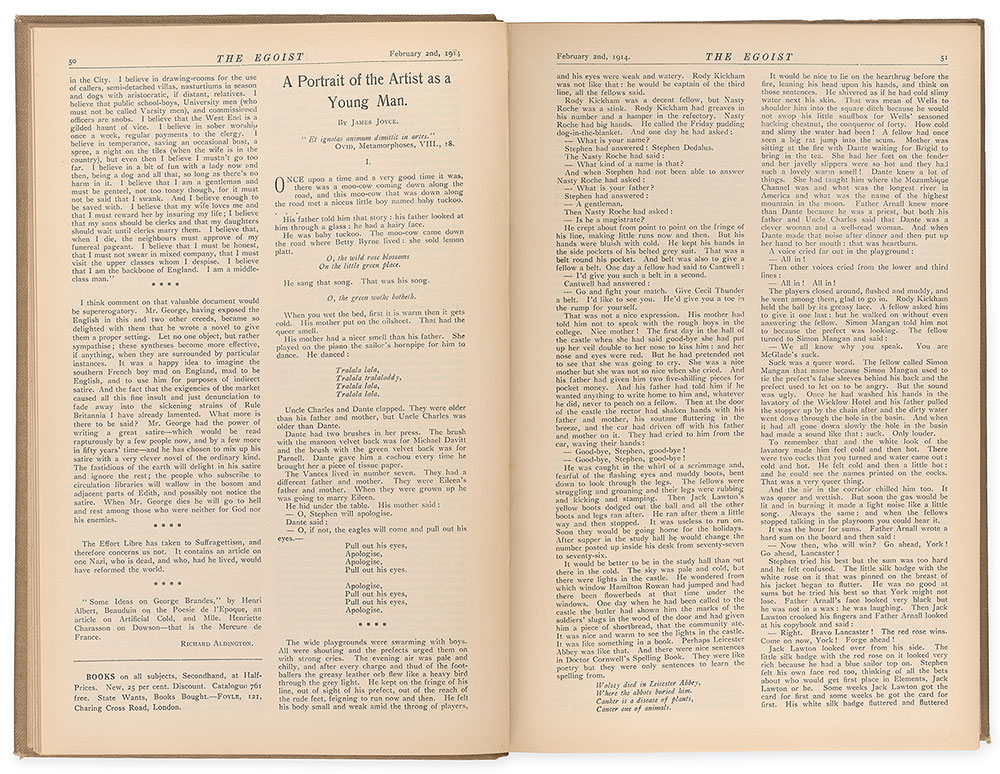

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

“When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight.

You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.”

–James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

James Joyce (1882–1941)

“A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”

In The Egoist: An Individualist Review 1, no. 3 (2 February 1914)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197802

© The Estate of James Joyce.

James Joyce’s first novel is a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and it began in serial form in The Egoist, which was a London magazine, edited by Dora Marsden and Harriet Shaw Weaver. Harriet Shaw Weaver would become very important to the life of Joyce, as she funded him to a large extent, so he could get on with his work in peace. Once the novel began to be serialized, of course, the problems that were always there began about the work’s content, and Harriet Shaw Weaver had to fire several of the magazine's printers, because they would censor words that referred to bodily functions.

The novel is a beautiful book about the growth of a young man, very much based on the life of Joyce himself, his Catholic education with the Jesuits, his home life, the life of his father, his time at University College Dublin. We watch as the style changes in the book from a sort of almost baby talk in the opening sentences to a very, very sort of fragmented ending of the book. And what we have in the book is an account of the growth of the artist who would someday soon write Ulysses.

Harriet Shaw Weaver and her Printers

Harriet Shaw Weaver, who took over the editorial reins of the Egoist shortly after Portrait's first excerpts appeared, confronted resistance from the magazine's printers over subsequent extracts from the novel. Similar to the opposition provoked by Dubliners, some of the language and subject matter in Portrait was viewed as unconventional by pressmen and potentially obscene. Weaver, dedicated to publishing Joyce's text exactly as he had written it, had to fire several of her magazine’s printers for their censoring of words such as “ballocks” and references to bodily functions. Those redactions were made after the printers had produced faithful type settings, however, which allowed the New York publisher B. W. Huebsch to restore the language for the book’s first edition in 1916. Weaver started the imprint Egoist Ltd. in order to publish Portrait in England. Although British printers persisted in their unwillingness to involve themselves in Joyce’s controversial work, Weaver was able to issue her edition by binding sheets that had been printed in America.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

London: Egoist Ltd., 1917 [i.e., 1918]

Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135606

Writing Ulysses: An Endlessly Changing Surface

The manuscript of Ulysses is a palimpsest of Joyce’s restless mind and holds the key to how his imagination worked. While the novel’s structure, based on the Odyssey, and its plotlines were stable, the act of writing for Joyce was filled with excitement and possibility. As well as the story of a day in Dublin, Ulysses is about style in narrative— how many systems can compete in a single page or episode. As Joyce worked, nothing was fixed.

Nothing was arguably fixed even after the book was published. There were slight changes--corrections and new errors--each time Ulysses appeared. An account by the scholar Luca Crispi in 2019 summed up the surviving evidence of Ulysses’ composition: 100+ pages of notes, about 39 handwritten drafts, 1,400+ pages of typescript, approximately 5,000 pages of galley and page proofs, and a fair copy manuscript of 800+ pages. The forms and volume of material related to the novel’s composition led to controversial efforts to establish a definitive text—a task that was not satisfied until the 1984 edition, edited by Hans Walter Gabler. For some scholars, that text was not entirely free from controversy. This section of the exhibition features some of Joyce’s plans and sources for the novel and considers his creative practice in manuscript and proofs through the lens of two episodes: “Sirens” and “Cyclops.”

Man Ray (1890–1976)

James Joyce, 1922

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; 2018.21

© 2022 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (AR), New York / ADAGP, Paris

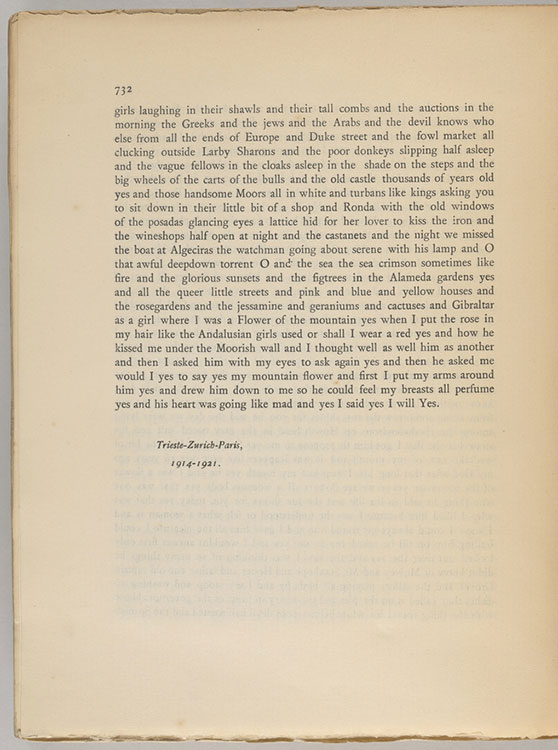

Molly Bloom and Nora's Style

In Ulysses Molly Bloom, the wife of Leopold, comes to life mainly in her husband’s thoughts. Throughout the day he contemplates her affair with a man called Blazes Boylan. Much more than an object of desire and jealousy, however, Molly is also the character who gets the last word. In the book’s final episode, “Penelope,” Molly is not merely breathless but also eloquent, not merely sexually frank but also an engaging narrator and storyteller. Studying Molly’s soliloquy alongside a 1904 letter on view in the gallery from Nora Barnacle to Joyce, one notices a similar lack of punctuation, the sense of pure voice unmediated by irony or craft or literary artifice.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922

The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135610

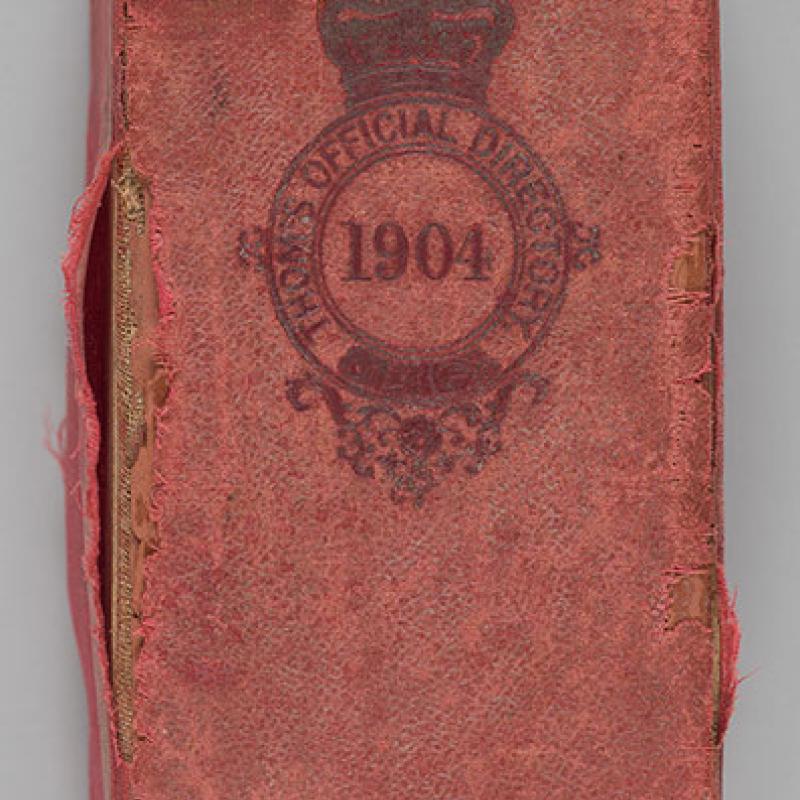

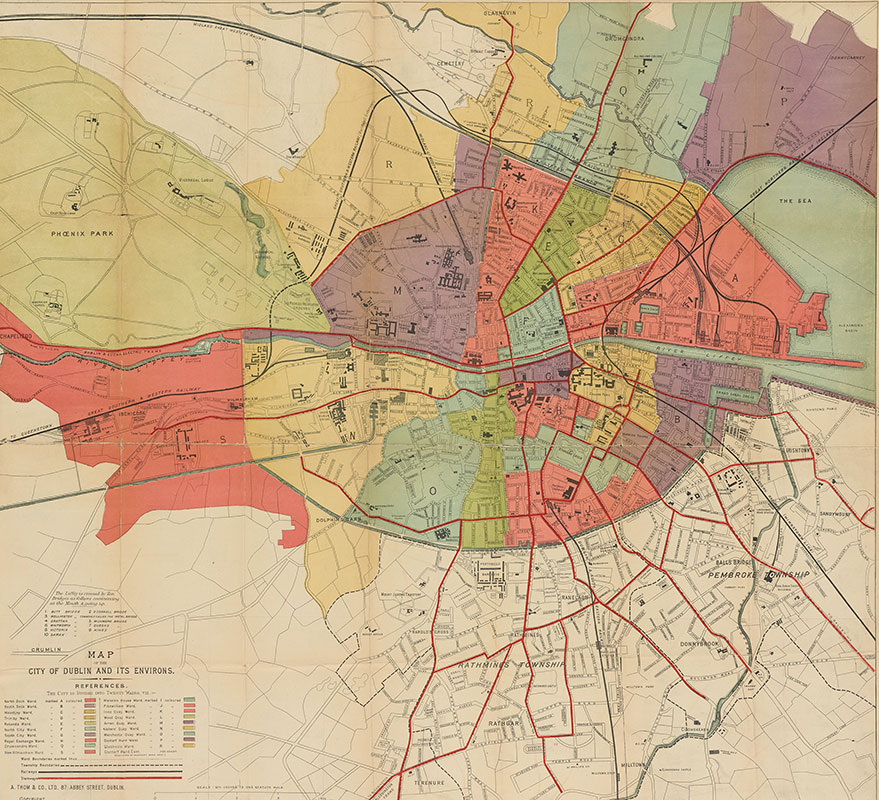

Thom's Dublin Directory

Joyce in exile relied on this residential and commercial directory of Dublin from 1904 to render the intricate urban fabric of Ulysses, which is set that same year. Published annually, Thom’s offers a wide range of information about Dublin, from hackney cab fares to racing calendars and listings of doctors. It contains a detailed street-by-street directory of the city as well as a large folding map. Joyce mined Thom’s for details to include in Ulysses, presenting Dublin with uncanny topographical and historical accuracy. The address 7 Eccles Street, the Blooms’ residence, was listed as vacant in 1904.

Vignette on binding of Thom’s Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (Dublin: A. Thom, 1904)

Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

A. Thom & Co.

Map of the City of Dublin and Its Environs, 1915

Courtesy the General Research Division, The New York Public Library

Writing Ulysses

“In writing one must create an endlessly changing surface . . .”

–James Joyce, from Arthur Powers’s Conversations with James Joyce

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses, manuscript of the first page of the “Telemachus” episode

Zurich, 1917

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia; EL4 .J89UL 922 MS

© The Estate of James Joyce.

While Joyce had a scheme for Ulysses, a structure, he knew what he was doing to that extent, but as he worked on the actual chapters, his mind became increasingly restless and his imagination, increasingly ambitious. So the very act of writing became for him an act of changing of possibility, of excitement, so that he was telling the story of these characters and their day in Dublin, but he was also setting about to create a sort of systems of style and systems of competing narratives, often in a single page, often in an episode, but usually in each episode having a different style. So he constantly revised the text to making many additions and emendations even as the book was being printed, he was making changes, of course, much to the puzzlement, astonishment, and annoyance of the printers.

Ulysses from Beginning to End

James Joyce (1882–1941)

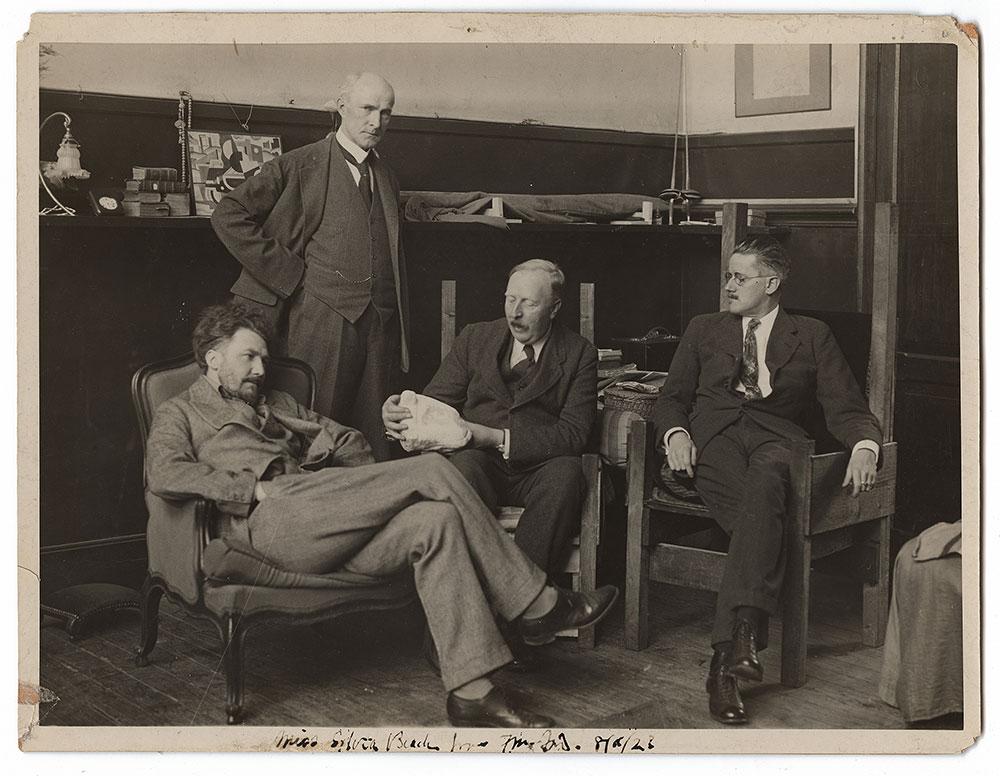

Ulysses, manuscript of the last page of the “Penelope” episode

Paris, 1921

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Ulysses begins with the word “stately.” In other words, a word with s, and y, and it finishes with “Yes,” in other words, a word with y, and s. And it is as though the letter s as beginning and ending the book is a sort of curl, or a way of beginning again, and the y with its with its two arms, as it were, up in the air. So that there's a sense that the book curves around itself that as it begins, it ends, and as it ends it begins. And this is part of I think the overall design of the book. I think you can never read too much into the book, that is the sense of every word is a key to another word, or even the way letters are made or even the way the pages are laid out, that all of it is part of a grand design.

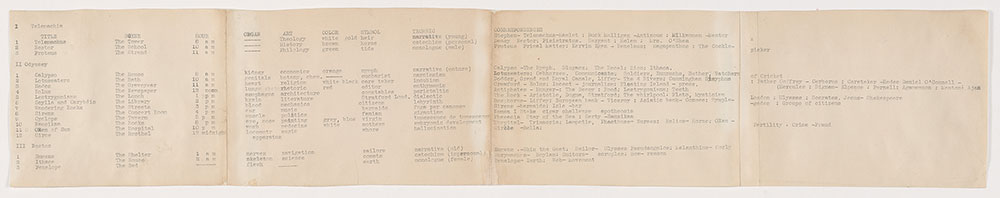

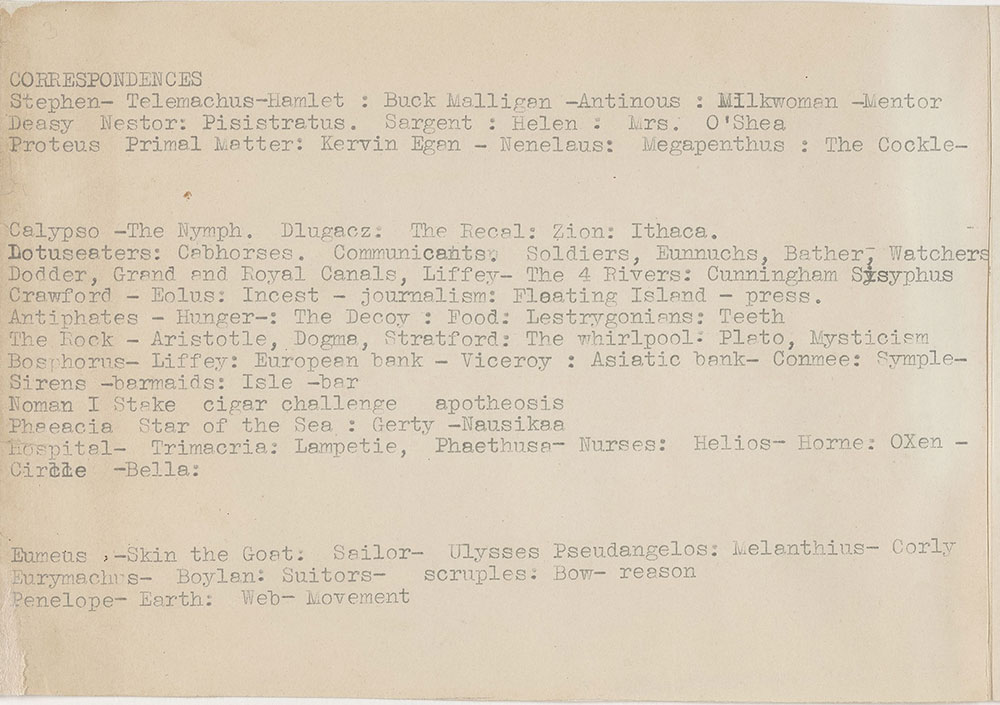

The Schema of Ulysses

Joyce created lists and charts to help plan Ulysses. This schema, as Joyce called it, diagrams the novel with respect to each episode’s symbol, color, art, organ, hour, scene, narrative technique, and Homeric correspondences. Joyce first collated notes in this scroll format to help certain writers discuss or translate parts of the work; he also made presentation copies for Harriet Shaw Weaver and Sylvia Beach around the time of the novel’s publication. The extensive Homeric links had been elaborated as he neared Ulysses’ completion, when Joyce sought to unify more motifs across episodes and clarify the structure. He later regretted the document’s unauthorized circulation, believing that it detracted from an appreciation of the novel’s overarching form and substance.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Typewritten schema of Ulysses, with detail

Prepared for George Antheil, Paris, ca. 1924

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197792.1

© The Estate of James Joyce.

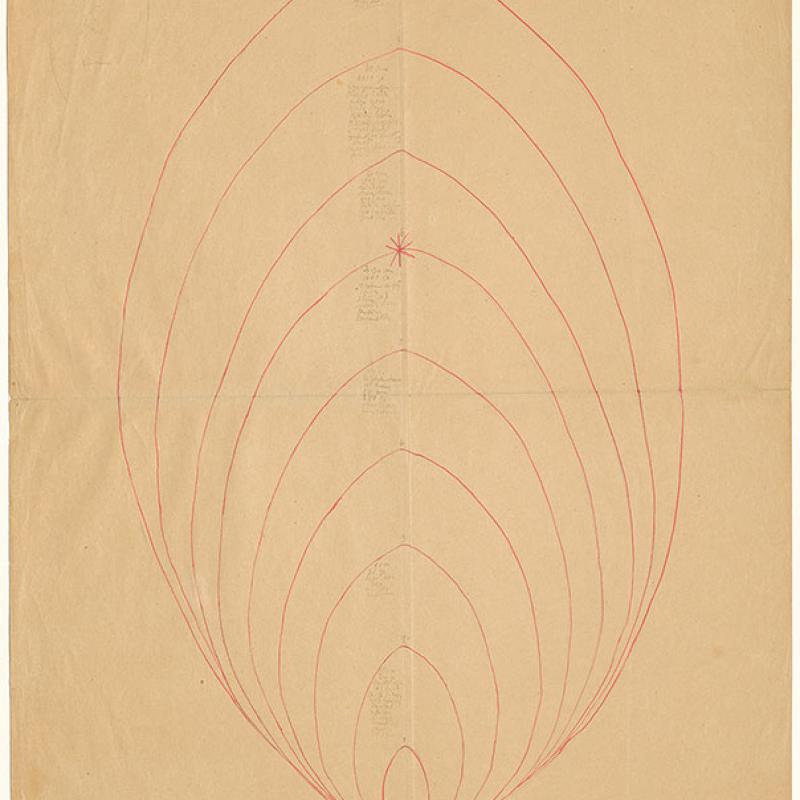

Embryological Chart for "Oxen of the Sun"

This is one of two versions of Joyce's diagram for "Oxen of the Sun"--an episode set in a maternity hospital. The near-illegible words track the month-by-month developments of a human fetus, paralleling the metamorphosis of language Joyce explores through pastiche. In a letter to Frank Budgen, dated 20 March 1920, Joyce wrote that he was hard at work on the episode—"the idea being the crime committed against fecundity by sterilizing the act of coition." Joyce related to Budgen a litany of the progression of literary styles he planned to employ, including a Sallustian-Tacitean prelude ("the unfertilized ovum"), early alliterative and monosyllabic English, Anglo-Saxon à la Mandeville, followed by Malory, the Elizabethan chronicle style, Milton, "Latin-gossipy," Burton, Browne, Bunyan, Pepys, Evelyn, Defoe, Swift, Addison and Steele, Sterne, Landor, and Pater, culminating in his identification of English, Irish, American, and Black vernaculars.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Embryological diagram for the “Oxen of the Sun” episode in Ulysses, 1920

James Joyce Collection, #4906, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Music in "Sirens"

Ottocaro Weiss (1896–1971)

James Joyce, Zurich, 1915

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The “Sirens” episode of Ulysses takes place at 4 pm at the Ormond Hotel on the Quays overlooking the River Liffey. Stephen Dedalus’ father Simon is there, his friend Ben Dollard is there. Leopold Bloom, the main protagonist of the book, enters the dining room. Now what happens in this episode is a sort of apotheosis, for Joyce, of how his father is to be presented in Ulysses. Simon Dedalus comes into the bar. He's not drunk, he's not annoying anybody, he's not a domestic nuisance, he is a man with a beautiful singing voice and everybody wants to hear him. And in this episode, he sings “M’appari” from Martha by Flotow and he’s followed by his friend Ben Dollard, who sings “The Croppy Boy” which is an Irish nationalist ballad. Bloom is in the other room listening to this. [Music begins]

I think this episode shows us more than anywhere else, the importance of music in Ulysses. That is how people are connected. Molly Bloom, Leopold Bloom’s wife, is a singer. Simon Dedalus is a singer. They have known each other for years and it's a very small world of professional and semi professional singers. [Music begins]

The Joyces and O'Sullivans Around the Piano

Unknown photographer

Nora Barnacle Joyce, Marguerite and John O’Sullivan, and James Joyce, Paris, ca. 1930s

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

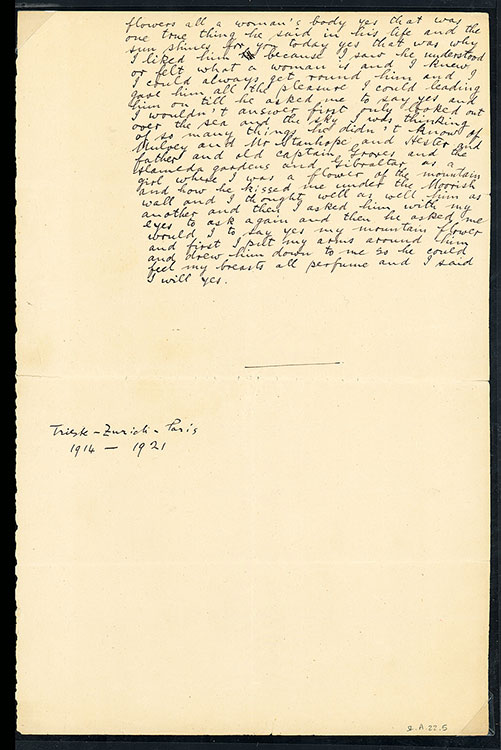

A Mosaic Piece from "Sirens"

Joyce always carried note pads and stray bits of paper in his jacket. According to the painter Frank Budgen, a friend of Joyce’s, “alone or in conversation, seated or walking, one of these tablets was produced, and a word or two scribbled on it at lightning speed.” This aspect of Joyce’s composition process led Budgen and writer Valery Larbaud to compare Joyce to a Renaissance mosaic artist, patiently fabricating large figures of the saints out of tiny pieces of colored stones.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Manuscript fragment from the “Sirens” episode, Zurich, [1918 or 1919]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; MA 9770

© The Estate of James Joyce.

"Sirens": The Fair Copy

This page of “Sirens” is taken from the “fair copy” manuscript of Ulysses—a term used to describe manuscripts created for presentation, rendered in legible handwriting. Joyce prepared this particular manuscript in order to sell Ulysses in installments to the collector John Quinn.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Manuscript page from the fair copy of the “Sirens” episode, Zurich, May 1919

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia; EL4 89ul 922 MS

© The Estate of James Joyce.

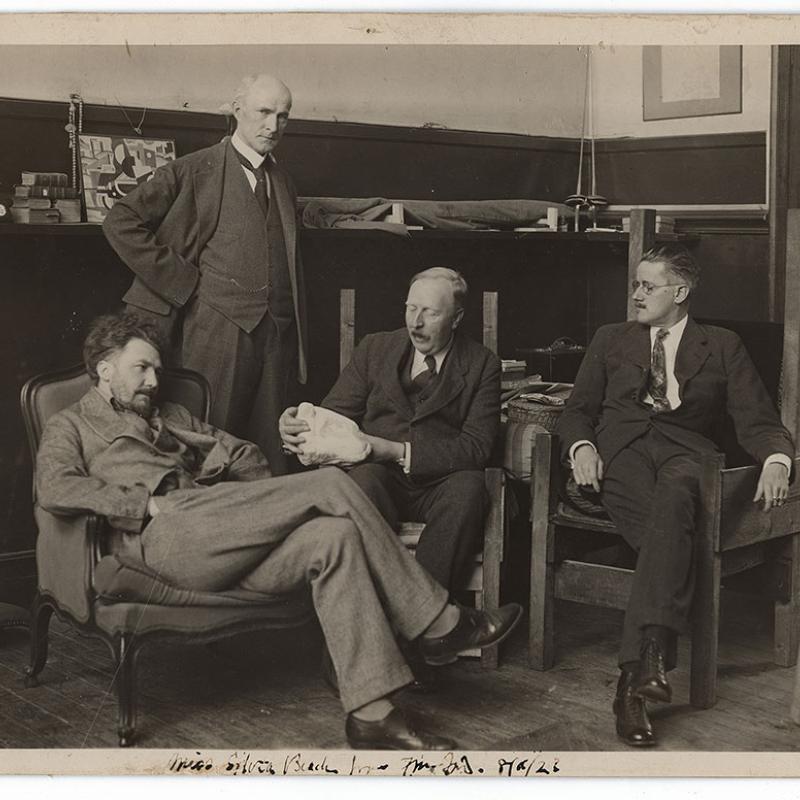

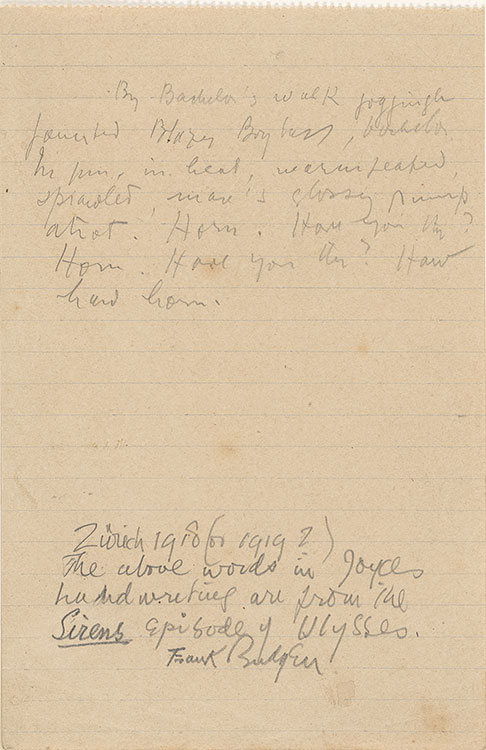

John Quinn

Before his play Exiles was published or performed, Joyce had sold the manuscript to the American modern art collector and lawyer John Quinn (1870–1924), shown here standing with Joyce and the authors Ezra Pound and Ford Madox Ford. As scholars have noted, the sale marked a new source of income for Joyce, who struggled to support his family, and signaled his growing status as an author. Quinn’s investment in Joyce persisted far beyond Exiles: he acted as the attorney for Anderson and Heap in the obscenity case against Ulysses in the Little Review and promoted Joyce to American publishers. Among several other works, Quinn purchased a “fair copy” manuscript of Ulysses as it was being written, enabling Joyce to finish the novel.

Unknown photographer

Ezra Pound, John Quinn, Ford Madox Ford, and James Joyce, Paris, ca. 1923

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

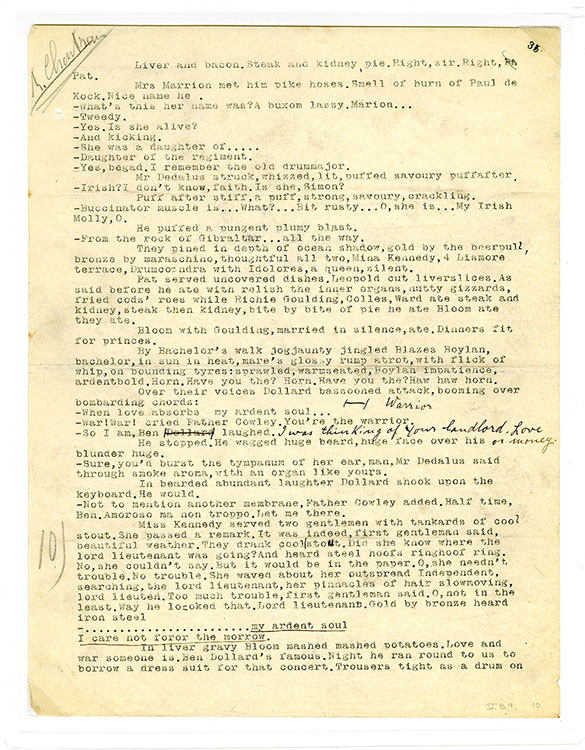

Typescript of "Sirens" for the Little Review

Joyce made several typed versions of manuscripts before and after sending fair copies to John Quinn. This page from “Sirens” was sent to printers at the Little Review, an American literary magazine, in 1919 for the novel's initial serialization. Joyce’s handwritten revisions date from 1921, however, as he was beginning to assemble and revise his text for the first edition in Paris.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Typescript from the “Sirens” episode for the Little Review, Zurich, July 1919

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

The Personal Politics of "Cyclops"

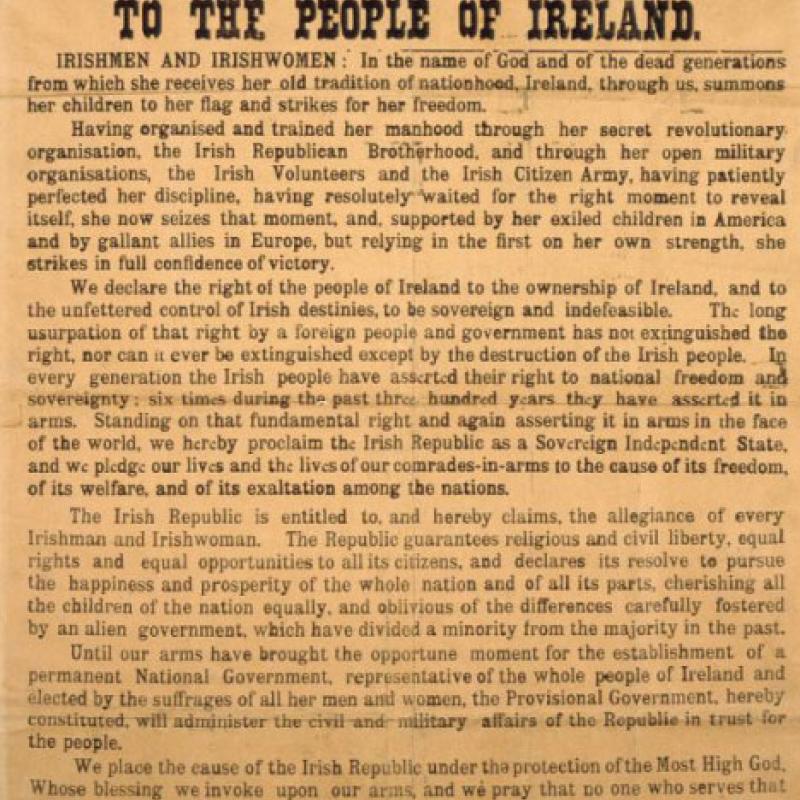

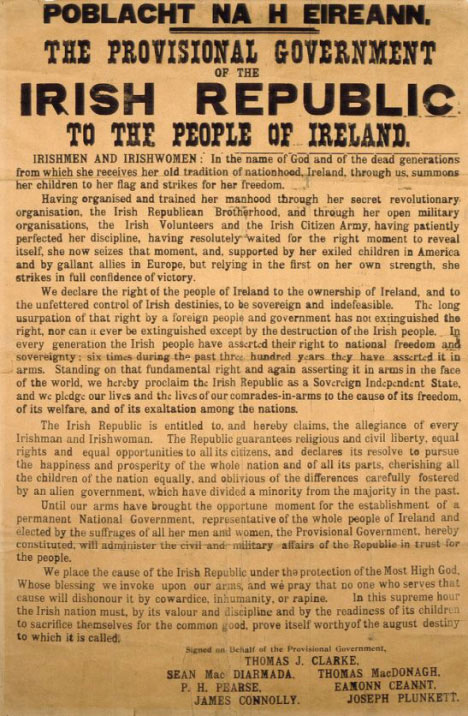

Poblacht na h’Eireann (The Irish Republic). The Provisional Government of the Irish Republic to the People of Ireland

[Dublin: s.n., 23 April 1916]

Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The episode known as “Cyclops” takes place at five o'clock in Barney Kiernan’s pub in Dublin. It is, I suppose, the most political episode in Ulysses, and also one of the most stylistically exciting. It was written in 1919, but Joyce did not deal directly in any way with the carnage of the First World War, or the 1916 Easter Rebellion in Dublin, or the ongoing War of Independence against British forces. It is emphatically set in 1904. However, there is a discussion about nations and violence and nationalism and it is, in a way, a veiled response to the very world that Joyce knew being torn apart. He had known Patrick Pierce, who was the leader of the Easter Rebellion, and his friend Francis Skeffington, was murdered on the third day of the Dublin Uprising. But “Cyclops” has its own internal explosions. That even though it is ostensibly set in a pub, with men talking, there are regular interruptions in the style of the episode, where there are parodies and pastiches inserted out of the blue as an exciting intervention of types of discourse that were common in Ireland at the time. So the chapter, stylistically, is hugely adventurous and totally exciting, but in the middle of it, are serious discussions about hatred, about history, and about violence, with Leopold bloom, arguing for a sort of pacifism against the nationalists who are drinking more than he is, and are more heated than he is. But he himself in this episode seems particularly articulate, and particularly serious.

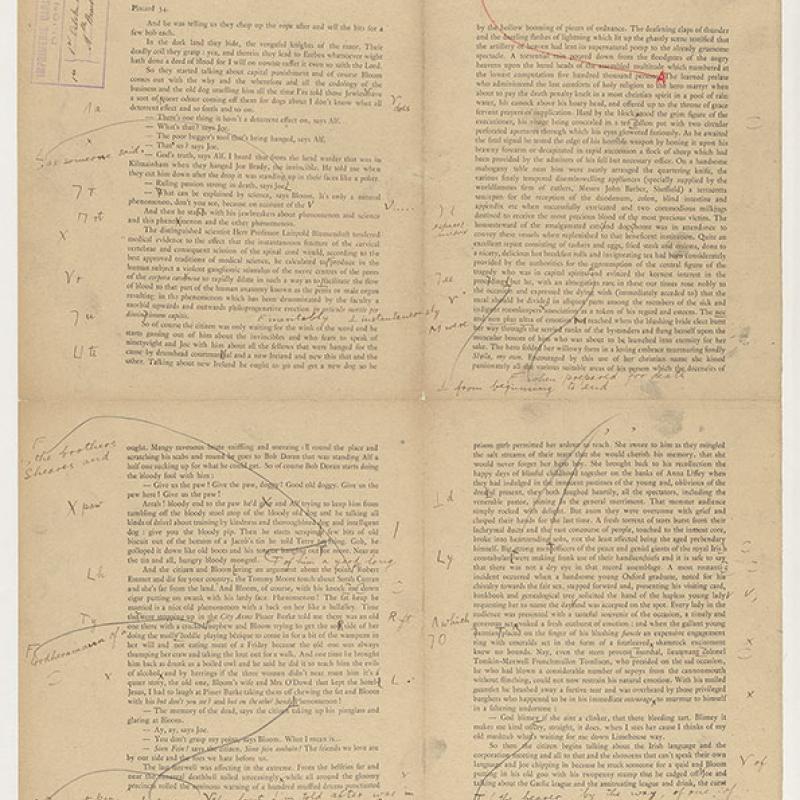

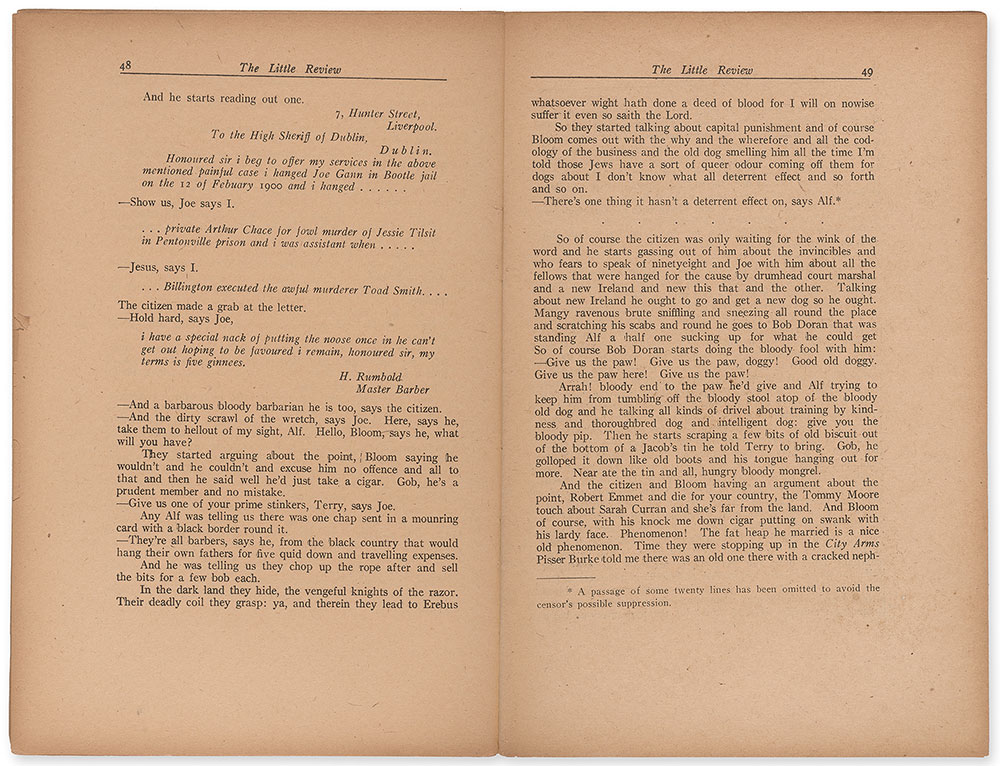

Censoring "Cyclops" in the Little Review

Among several manuscripts and proofs on view related to "Cyclops" are two pages of what is likely the earliest surviving preliminary draft of the episode and a leaf from the 1919 typescript sent to the Little Review, revised two years later. "Cyclops," as Joyce originally wrote it, never appeared in the magazine in its entirety. Following the US Postal Service’s suppression of two Ulysses issues, the editors preemptively censored the first installment of “Cyclops.” One of Joyce’s passages, which alludes several times to erections, was replaced with an asterisk, an ellipsis, and a telling footnote.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses [the “Cyclops” episode]

Little Review 6, no. 7 (November 1919)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197868.8

© The Estate of James Joyce.

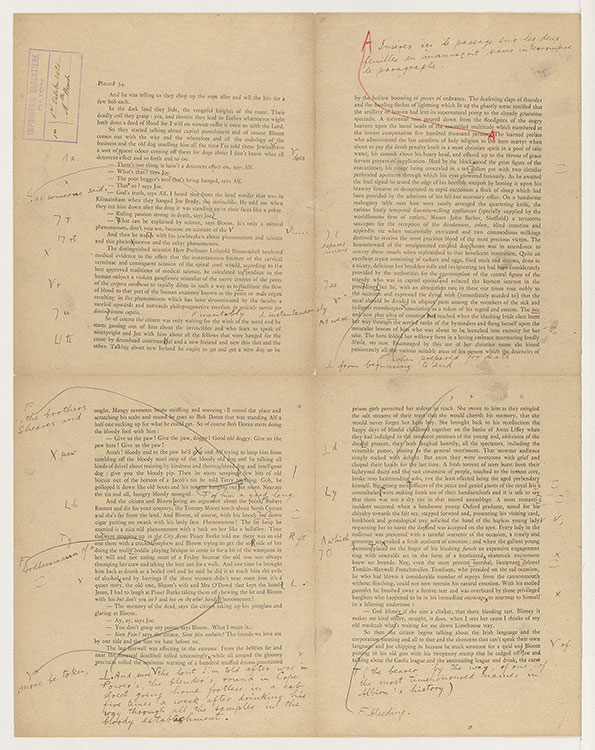

"Cyclops" and Borus Hupinkoff

Joyce reportedly wrote a third of Ulysses in proof—a stage in the publishing process that is typically reserved for minor corrections and additions. The large, eight-page format of French galley proofs on view in the gallery, known as placards, offered ample marginal space to accommodate Joyce’s creative practice. This detail of a "Cyclops" placard pertains to one of the passages that Joyce revised most heavily. In addition to the long marginal inscriptions, Joyce’s note in French, indicated with a red A, instructs the printer to insert two new manuscript pages, one of which is on view adjacent to the placard. The lengthy handwritten addition includes a list of “Friends of the Emerald Isle,” parodic names such as “Commendatore Bacibaci Beninobenone” and “Monsieur Pierrepaul Petitépatant.” Across several stages of the proofs, the dignitaries expanded in number. In a brief note sent to Darantiere's manager, M. Hirchwald, Joyce conveyed another late addition named “Borus Hupinkoff” along with a postscript complaining about imperfections in their typographic character f. A pressman marked his request “trop tard” (too late) and Borus did not appear in editions of Ulysses for sixty years.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Detail of Placard 34 for the “Cyclops” episode in Ulysses

[Dijon: Maurice Darantiere, October 1921]

Houghton Library, Harvard University, part gift of Marian Willard Johnson in memory of Sylvia Beach, and part purchase with funds from the Amy Lowell Fund, 1969; Ms Eng 160.4 (83)

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Manuscript additions to placard 34 for the “Cyclops” episode, Paris, 1921

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

How do you finish a novel as ambitious as Ulysses? As Joyce worked on the final episodes of the book, he also began to transform earlier episodes, he went back and back, hardly ever deleting, mostly adding, and in total excitement, sometimes, with lists of names, he would think of another name to add. There's a parodic list of names called Friends of the Emerald Isle, and they include all sorts of ridiculous people, with ridiculous names. Some of it’s very, very funny, but just as the book was going to press, just as the printers were working on getting it ready, Joyce told him one more name he wanted in the list. The name was “Borus Hupinkoff,” which Joyce thought was tremendously funny, and he sent it off telling the printers exactly where it should go. But it was too late. They wrote back saying, “trop tard,” and that name did not make its way into the 1922 edition of Ulysses. It had to wait until the Hans Walter Gabler edition appeared in the 1980s. So for sixty years, that name was wandering the Earth. It did not make its way into print, but it's part of the extraordinary energy that Joyce put in to completing his book, and then thinking it wasn't complete wanting one more thing, wanting to rewrite to add to amend, completely unsatisfied, no matter how close he was to the end.

Publishing Ulysses

In 1904 Joyce lived in a tower overlooking Dublin Bay. This experience would inspire Ulysses’ first episode, which introduces the young poet Stephen Dedalus. Leopold Bloom, at the novel’s center, is both a cuckolded husband and a figure of rare dignity and humanity. The book takes its structure from Homer’s Odyssey, but it encompasses the language of mass culture. Among the novel’s innovations is its use of stream of consciousness, tracing Stephen’s then Bloom’s thoughts as they wander through Dublin and Molly Bloom’s as she lies in bed.

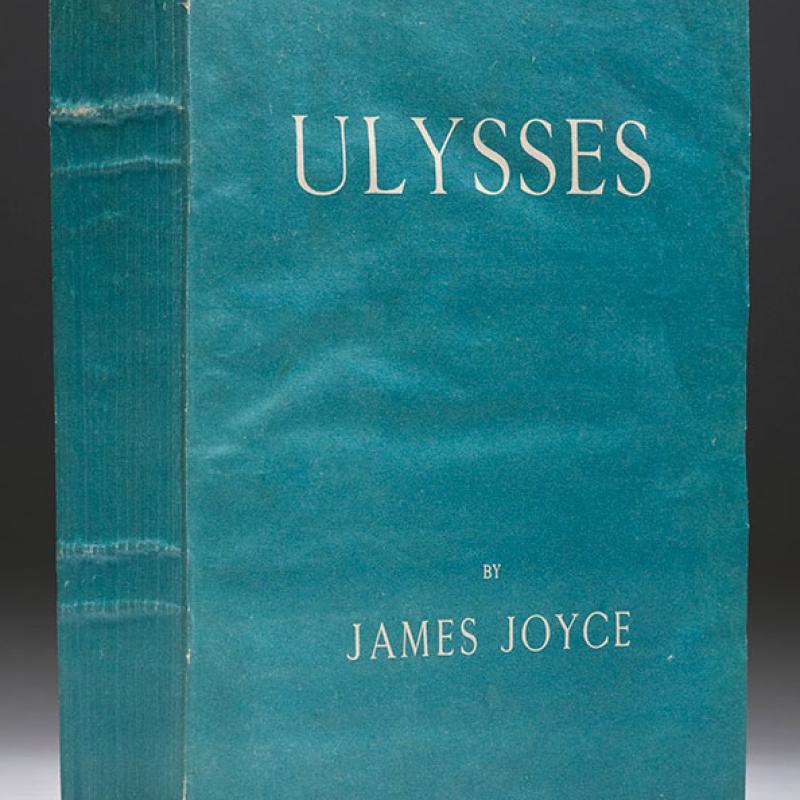

Joyce struggled to find a publisher willing to take on his novel, largely due to its graphic passages— especially after its serialization in America resulted in an obscenity ruling. Disconsolate, Joyce feared that his book would never come out. In early 1921, however, Sylvia Beach, an American owner of a Paris bookstore, agreed to issue a private edition in France. Published on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s fortieth birthday, Ulysses appeared a month after the treaty establishing Irish independence from Great Britain was approved in Dublin. The book and the country it explores began their new lives in 1922.

Assorted copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses and other works

The Morgan Library & Museum, gifts of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018.

Joyce had many supporters as he wrote Ulysses, including Harriet Shaw Weaver, who supported him financially, including Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, who published some episodes of Ulysses in the Little Review in the United States, and including Sylvia Beach in Paris, who realized the problems Joyce was going to face. The book was going to be censored, both in the United States and in the United Kingdom. She was based in Paris where she had a bookstore and she decided, by asking people to subscribe to the printing to actually publish the book privately to make sure that it did appear on Joyce's fortieth birthday, the second of February 1922.

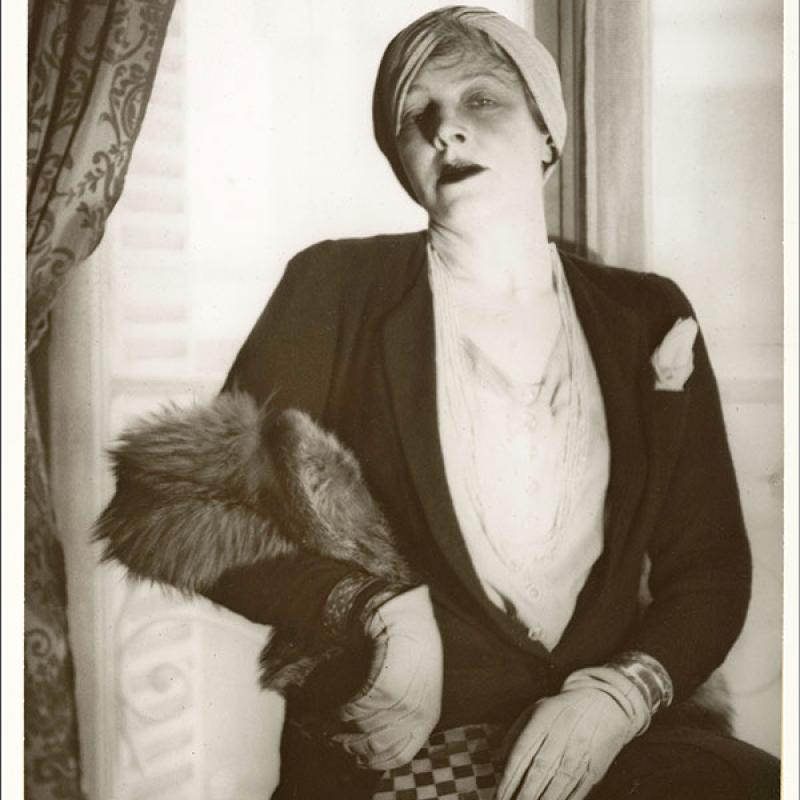

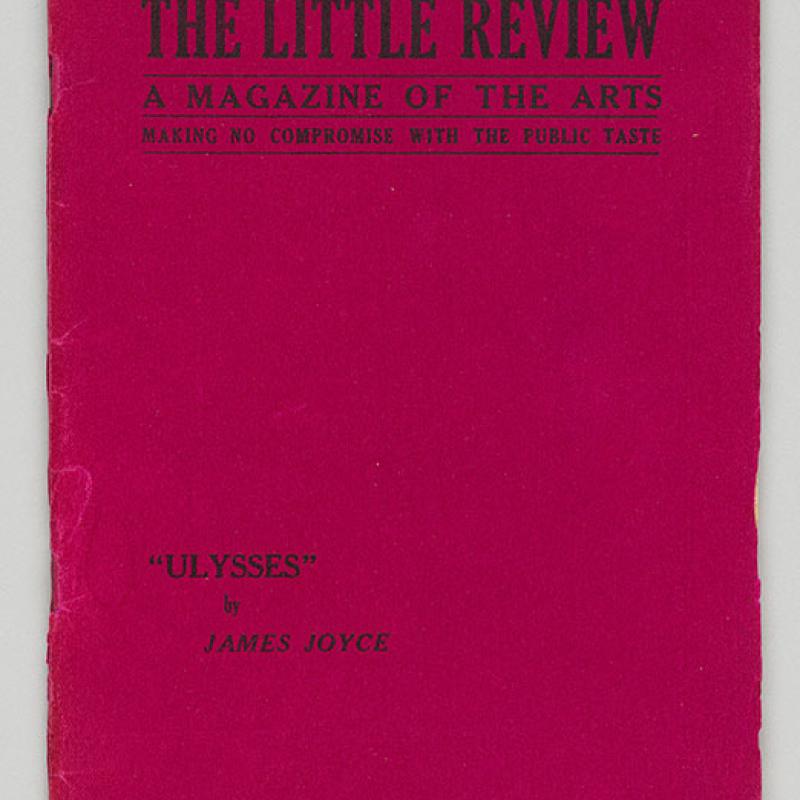

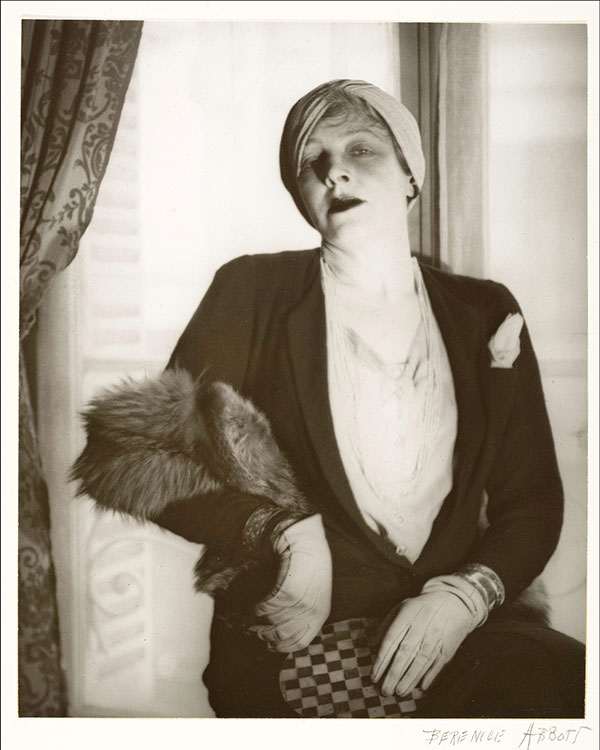

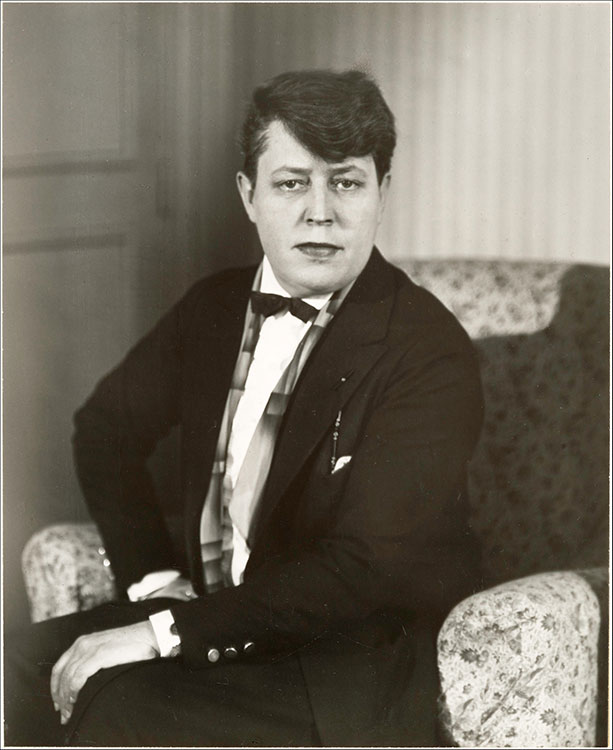

Ulysses in the Little Review

Margaret Anderson (1886–1973) founded the American literary magazine the Little Review in 1914. Her friend and partner Jane Heap (1883–1964) became the art editor, and Ezra Pound served as foreign editor. Together they helped shape a version of literary modernism, publishing writers such as Gertrude Stein, Wyndham Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, Djuna Barnes, T. S. Eliot, and Jean Toomer, one of the few Black writers included in their enterprise. When Margaret Anderson read the beginning of Ulysses in February 1918, she vowed to print it “if it’s the last effort of our lives.”

Berenice Abbott (1898–1991)

Margaret Anderson, ca. 1928, printed later

Gelatin silver print

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Laura May Isaacson, 1976; 1976.601.1

Berenice Abbott (1898–1991)

Jane Heap, ca. 1928, printed later

Gelatin silver print

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Laura May Isaacson, 1976; 1976.601.2

© Berenice Abbot via Getty Images

The Case Against "Nausicaa"

The first of twenty-three installments of Ulysses appeared in the Little Review in March 1918. Between 1919 and 1920, the US Postal Service confiscated four issues because they violated the Comstock Act, which prohibited the distribution by mail of printed matter deemed obscene. The issue containing an excerpt from the “Nausicaa” episode also provoked a court case against editors Anderson and Heap. In the offending passages, Leopold Bloom masturbates as he watches Gerty McDowell, a young woman who indulges him by leaning back and raising her skirt. Lawyer John Quinn’s defense—essentially, that Ulysses was not obscene since it was unintelligible to average readers—was a misfire. Anderson and Heap were fined, and the novel was banned in the United States.

Little Review 4 [i.e., 5], no. 11 (March 1918) [cover] and 7, no. 2 (July–August 1920) [the "Nausicaa" episode]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Annette De La Renta in Memory of Carter Burden, 2005; PML 129665

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Ulysses in Paris

Unknown photographer

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in the doorway of Shakespeare and Company, 8, rue Dupuytren, Paris, 1921.

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Sylvia Beach

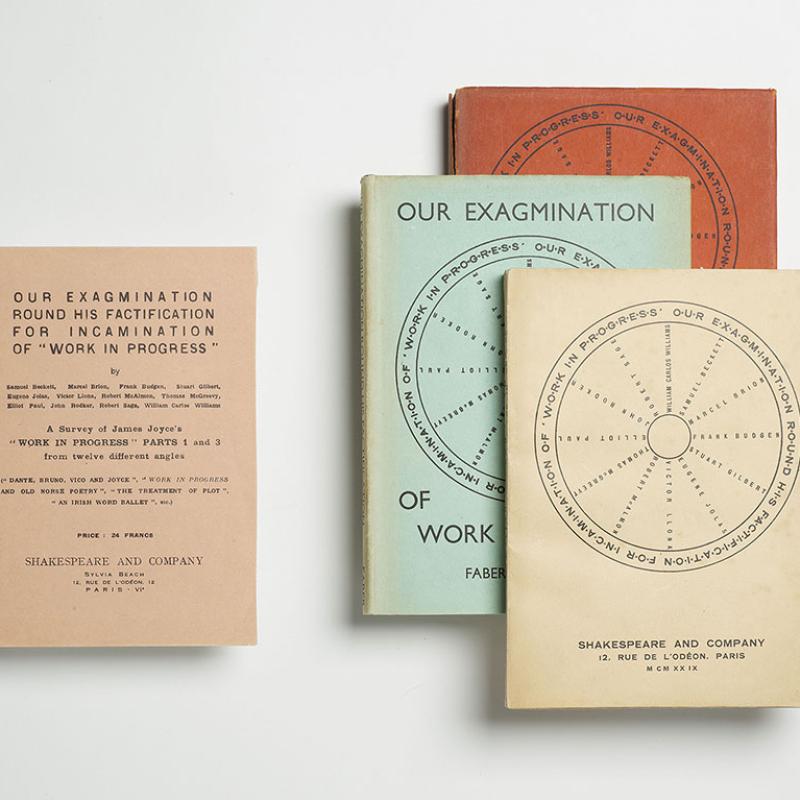

Sylvia Beach (1887–1962) grew up in Baltimore, Paris, and Princeton, settling permanently in France in 1916. She opened Shakespeare and Company, an English-language bookshop in Paris, in 1919. In February 1921 she began helping Joyce find typists for Ulysses and, by April, agreed to bring out the novel herself. Beach published the book eight times between 1924 and 1930, reportedly selling twenty-eight thousand copies. As a US citizen, Beach was briefly interned during the German occupation of France in 1941, the year Joyce died, and her shop never reopened. In her later years, Beach gave George Whitman her blessing to change his bookstore’s name to Shakespeare and Company, which remains in business today.

Paul-Émile Bécat (1885–1960), Portrait of Sylvia Beach, 1923. Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Shakespeare and Company

Sylvia Beach started her imprint Shakespeare and Company in 1921 in order to publish Ulysses (she would issue two other books and one audio recording, all by or about Joyce). In its early days, Shakespeare and Company was primarily a secondhand bookstore and lending library. Beach soon expanded her inventory to feature the latest modernist books and magazines, turning the small shop into a hub for savvy locals, expatriates, and tourists. Joyce met Beach shortly after moving to Paris in June 1920, and he joined the shop’s lending library later that year. The first book he borrowed was apparently The Master Builder by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906).

Advertising card for Shakespeare and Company

[Paris: Shakespeare and Company, after 1920]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197834

Signboard for Shakespeare and Company

Marie Monnier-Bécat (1894–1976)

Signboard for Shakespeare and Company, Paris, after 1920

Enamel on metal

Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

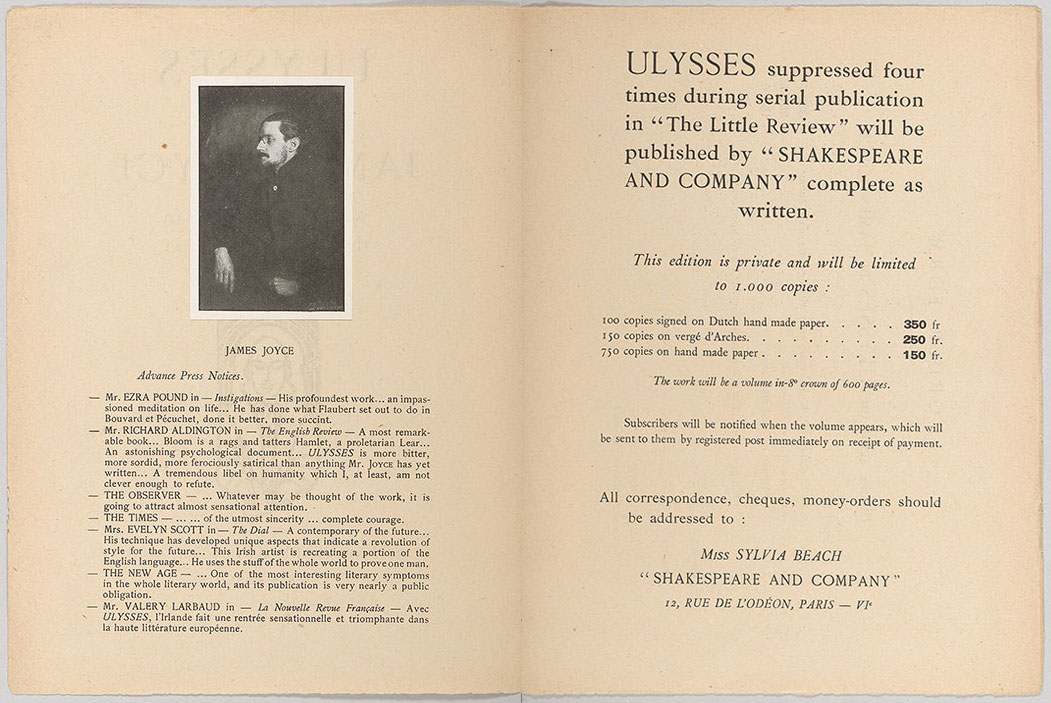

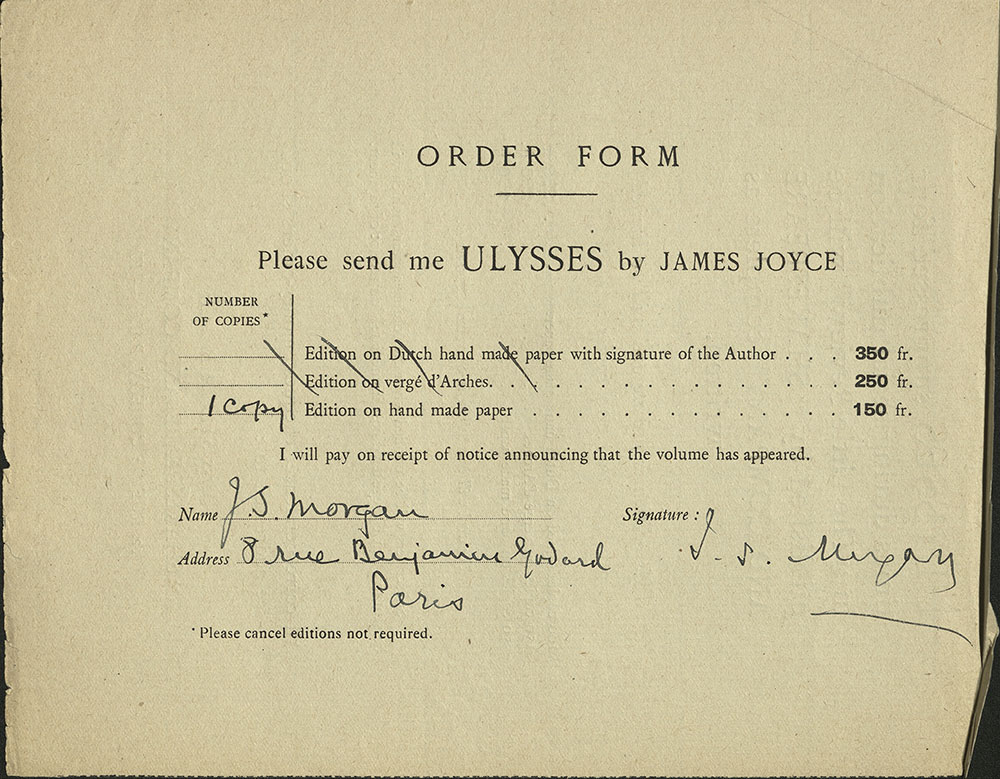

Prospectus for the First Edition of Ulysses

Soliciting subscriptions for Ulysses was imperative for Sylvia Beach to finance the hefty publication. This approach also designated the book a “private edition,” which diminished legal risks. Customers could order one of three versions, priced according to the fineness of their paper; the most expensive version was signed by Joyce. In 1921 and 1922 Beach printed hundreds of circulars such as this one and mailed them to individuals and bookshops around the world. Her forecast of a six-hundred-page book to be published in autumn 1921 proved optimistic. After the novel appeared on 2 February 1922, Beach annotated this circular accordingly: Ulysses was “now ready,” and the page count was 732.

Subscribers' bulletin for Ulysses by James Joyce

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, [1921]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197831-32

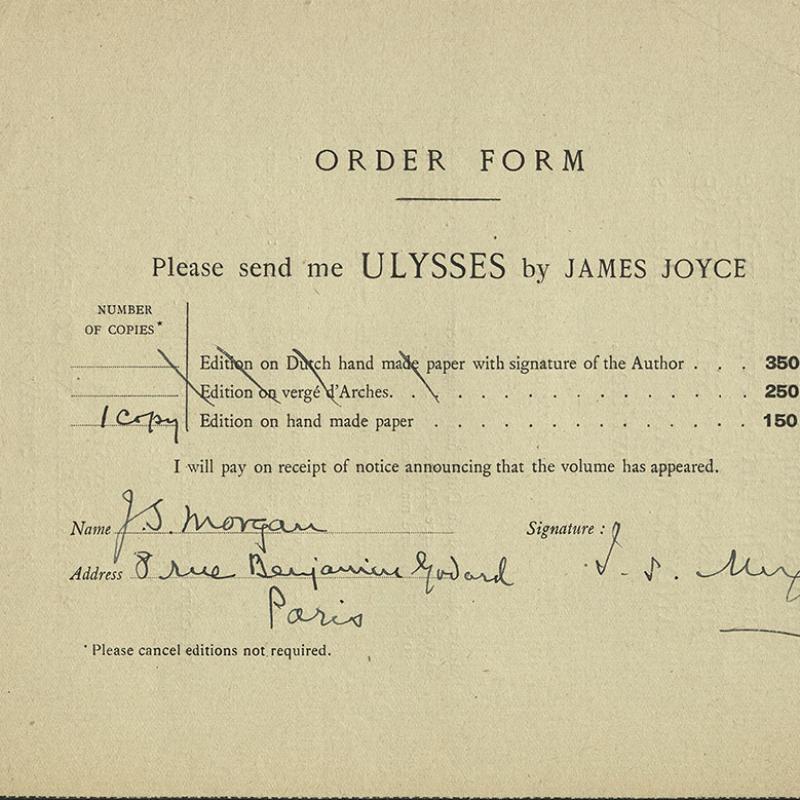

J. Pierpont Morgan's Nephew Subscribes

Orders for Ulysses began to arrive in Sylvia Beach’s shop soon after she circulated her prospectus in spring 1921. Many early sales were to bookshops, including several in Paris, and to firms that exported books to Europe and America. These customers received what was a modest trade discount in 1922, and they could—and often did—inflate the price thereafter. J. Pierpont Morgan’s nephew Junius Spencer Morgan (1867–1932) ordered his personal copy directly from Beach.

Junius Spencer Morgan’s order form for Ulysses, 1921/22

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

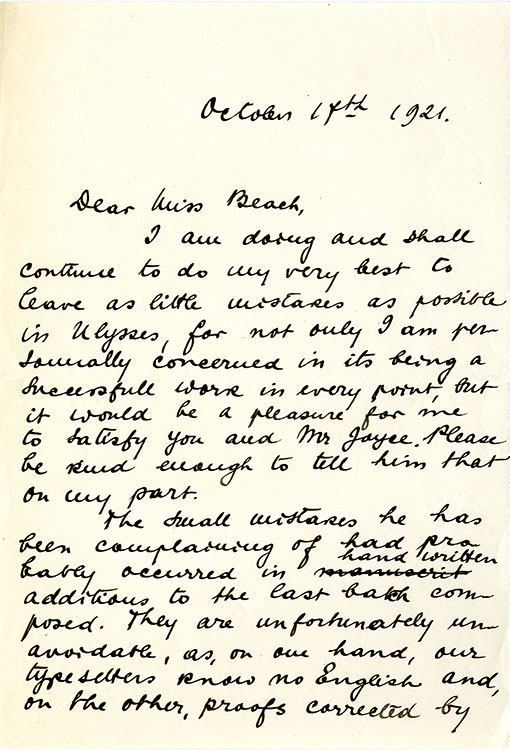

Letter of Protest from a Printer

In this letter to Sylvia Beach, a man named Hirchwald—the only English-speaking employee at Maurice Darantiere’s printshop—protests Joyce’s complaint about errors in the latest Ulysses proofs. Joyce was writing and proofing simultaneously, as he told a friend: “[I] am working like a lunatic, trying to revise and improve and connect and continue and create all at the one time.” Hirchwald blames Joyce’s handwritten additions for the errors, reminding Beach that his colleagues cannot read English. Promising to fix these “small nuisances” in his final proofreading, scholars have proven that Hirchwald in fact introduced new errors when correcting his typesetters’ work.

M. Hirchwald

Letter to Sylvia Beach, 11 October 1921

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

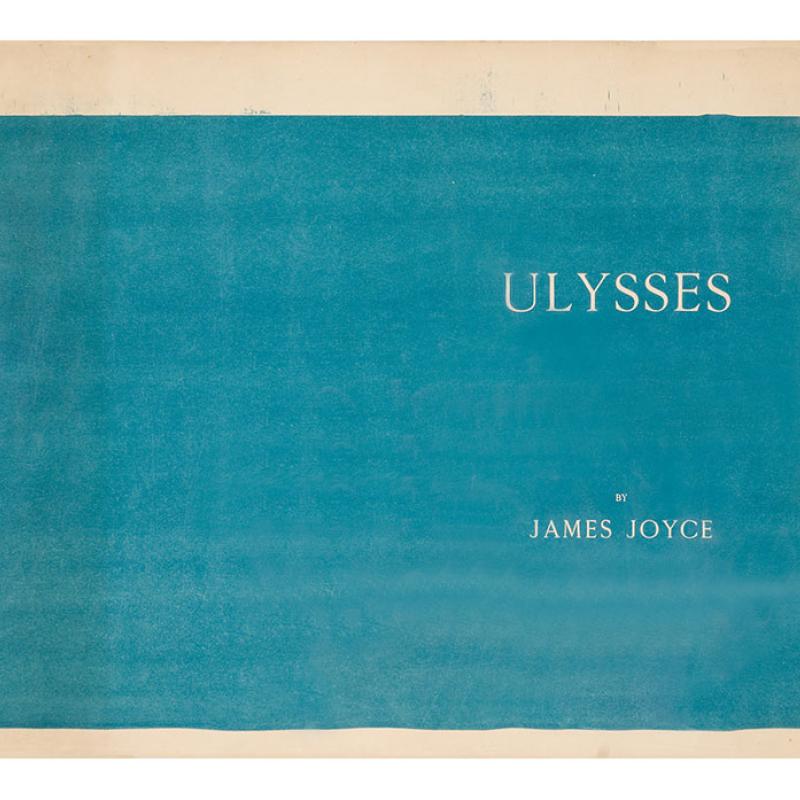

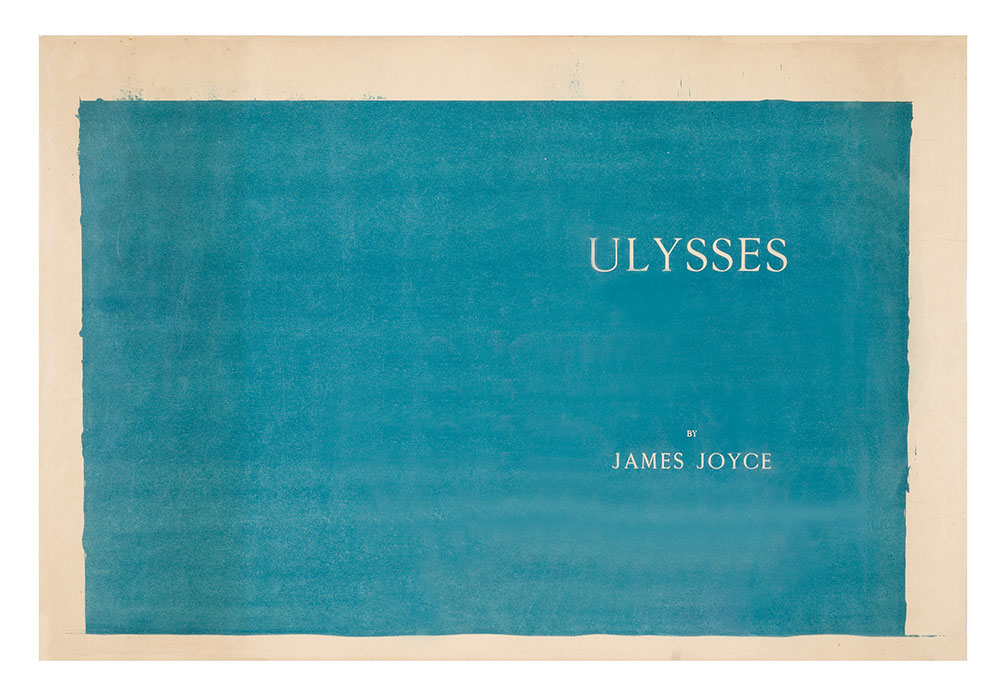

Getting the Right Blue on the Cover

Tasked with the challenges of typesetting Joyce’s ever-changing text, the printer Maurice Darantiere also faced difficulties related to Ulysses’ cover. Joyce’s long-held superstitions that Greece brought him good luck led him to insist that the book be bound in the colors of the Greek flag—blue and white. Darantiere provided Joyce with sample after sample of blue paper, none of which satisfied the finicky author. Less than a month before publication day, Joyce sent the small Greek flag hanging in Shakespeare and Company to the artist Myron C. Nutting, asking him to identify the right pigment. Darantiere then lithographed the “Greek-flag blue” onto white paper.

Final proof of cover for Ulysses

Lithograph

[Dijon: Maurice Darantiere, 1922]

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Publication Day

On 7 August 1921, Joyce wrote to Harriet Shaw Weaver to announce that he had composed the first sentence of Ulysses’ final episode, adding,“but as this contains about 2500 words the deed is more than it seems to be.” (In fact, the first sentence would be even longer, and the “Ithaca” episode was also far from complete.) Months later, he was still revising the text and checking facts, writing to his aunt, for instance, to make sure “an ordinary person” could climb over the railings at the Blooms’ Eccles Street address. Joyce continued to work on proofs through the end of January 1922.

Superstitious about his birthday, Joyce was determined that Ulysses be ready on 2 February. Few copies were bound on 1 February, but the printers granted Joyce’s wish, dispatching three copies by express mail and, at the author’s insistence, two more on the Dijon–Paris train, which were in his hands by early morning. In her memoir, Sylvia Beach recalled the momentous day: “Here at last was Ulysses. . . . Here were the seven hundred and thirty-two pages ‘complete as written,’ and an average of one to half a dozen typographical errors per page.”

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922

The Morgan Library & Museugift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018, PML 197791

Ulysses Account Rendered

Beach’s earliest surviving record of costs accrued for promoting, printing, and shipping Ulysses was compiled almost six months after the novel’s publication. Joyce’s relentless revisions and additions to the proofs reduced Beach’s initial profits; the printing costs were double what Maurice Darantiere had estimated in 1921. The unusual nature of Joyce’s professional relationship with Beach, who acted at times as his agent, secretary, and friend, is also evident in her bookkeeping, which includes fees for the seventeen-volume edition of Arabian Nights Joyce requested and for Dr. Borsch, the eye doctor Beach recommended to the author.

Sylvia Beach (1887–1962)

“Ulysses Account Rendered” for Shakespeare and Company, Paris, 27 July 1922

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Joyce's Recording of Ulysses

This is one of the two recordings of Joyce’s voice—a reading of John F. Taylor’s speech from the “Aeolus” episode of Ulysses, recited by the author in a Cork accent. Sylvia Beach, who commissioned the disc, had planned to invite journalists to the session, but the producer at the record label His Master’s Voice was not interested in publicity. He foresaw no profit (voice recordings by authors were anomalies in 1924) and insisted the label’s name be kept out of it. Of the twenty or thirty pressings Beach authorized, all but a handful soon broke into pieces. To this day, it remains Joyce and Beach’s rarest “publication.”

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses (pp. 136–137)

78 rpm audio disc

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1924

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197880

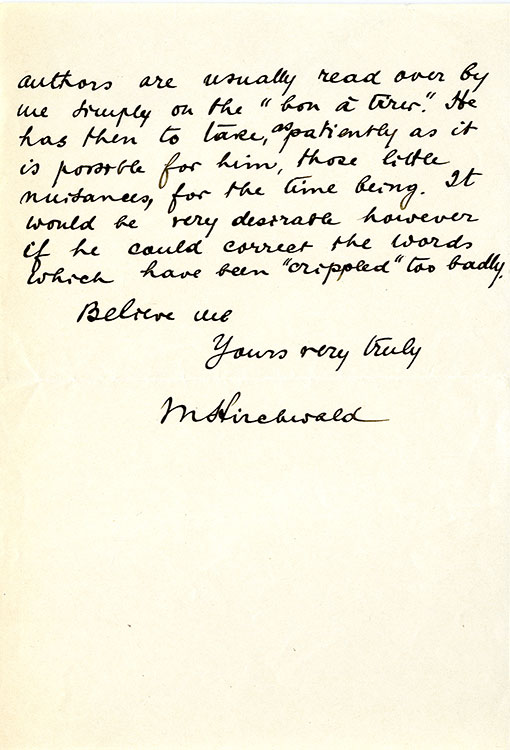

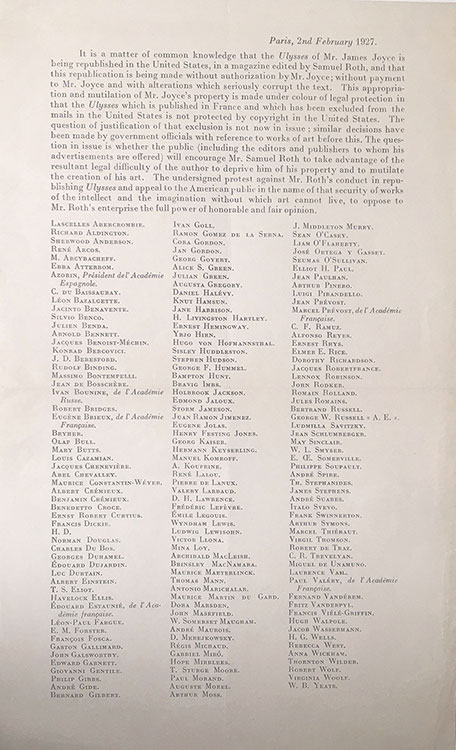

Adrienne Monnier's Déjeuner "Ulysse"

In 1929, fifty kilometers from Paris in the Chevreuse Valley, Adrienne Monnier hosted a luncheon at the Hôtel Léopold to celebrate her publication of the French translation of Ulysses— an enormous undertaking, years in the making. Since Joyce’s arrival in Paris in 1920, Monnier elevated his reputation among prominent French writers. She hosted the first conference on Ulysses in 1921 at her bookstore, La Maison des Amis des Livres, which prompted the first substantial translations of excerpts from the novel. Joyce called her Déjeuner “Ulysse” a “country picnic,” though guests were chartered on a special bus and Monnier had the menu printed as a keepsake. The meal kicked off with paté de Léopold.

Déjeuner “Ulysse”: jeudi 27 juin 1929, Hôtel Léopold, Les Vaux de Cernay

Paris: [Adrienne Monnier] printed by Société génerale d’Imprimerie et d’édition, 1929

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197798

Unknown photographer

James Joyce and guests at the Déjeuner “Ulysse”, Les Vaux de Cernay, 27 June 1929

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Édouard Dujardin

The writer Édouard Dujardin (1861–1949), who attended Monnier's Ulysses banquet and signed this copy of the keepsake menu, was credited in France in the late nineteenth century as the innovator of the stream-of-consciousness technique in narrative. Joyce had become familiar with Dujardin's work during his brief stint in Paris in 1902. More than twenty years later, when A Portrait of the Artist as Young Man was published in France, Dujardin became aware of certain similarities in their work—a connection that had also come to the attention of French critics regarding Joyce's version of stream of consciousness employed in Ulysses. Dujardin's career subsequently underwent a renaissance, which he credited to Joyce's fame in France. Joyce himself conceded his debt to Dujardin. In a copy of Ulysses inscribed to the French author, Joyce signed it "the impenitent thief."

Déjeuner “Ulysse”: jeudi 27 juin 1929, Hôtel Léopold, Les Vaux de Cernay

Paris: [Adrienne Monnier] printed by Société génerale d’Imprimerie et d’édition, 1929

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197798

Ulysses in London

Harriet Shaw Weaver was determined to find a publisher for Ulysses as early as 1918, when her proposal to Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press was refused. In early 1920, Weaver signed a contract to bring out the novel herself. By the time she printed this announcement in 1921, however, Joyce had already signed a publishing agreement with Sylvia Beach, whose Shakespeare and Company edition of Ulysses was priced too high for most readers. Both for financial reasons and as a democratic imperative, Weaver planned to issue a cheaper “ordinary edition.” Beach was skeptical that the novel would ever be legal in Britain and resented Weaver for threatening her own advance sales.

Harriet Shaw Weaver (1876–1961)

Prospectus for Ulysses by James Joyce

London: Egoist Press, 1921

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197833

Wyndham Lewis's Portrait of Harriet Shaw Weaver

Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957)

Portrait of Harriet Shaw Weaver, 1925

Graphite and unknown medium

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust / Bridgeman Images

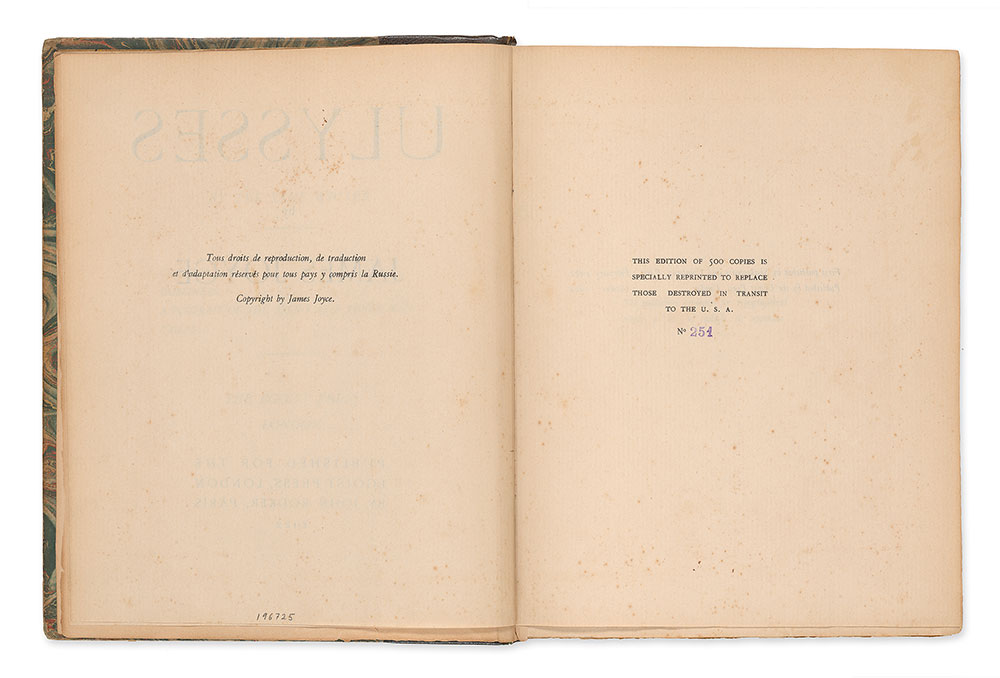

An Egoist Copy Saved from the Fire

Harriet Shaw Weaver was finally able to bring out her Egoist Ulysses in an edition of two thousand copies in October 1922. To evade legal troubles in England, she partnered with John Rodker to print it in France, from Sylvia Beach’s typeset plates. Bound in the same blue wrappers, its resemblance to the first edition initially unsettled Beach.

Harriet Shaw Weaver was finally able to bring out her Egoist Ulysses in an edition of two thousand copies in October 1922. To evade legal troubles in England, she partnered with John Rodker to print it in France, from Sylvia Beach’s typeset plates. Bound in the same blue wrappers, its resemblance to the first edition initially unsettled Beach.

In December 1922 Weaver learned that US Customs had seized up to five hundred copies of her shipment to America, prompting her to commission five hundred replacements from the printer right away. Joyce took the opportunity to correct some of the hundreds of errors made by the French typesetters in the Beach’s first edition. The replacements never made it to America either, however, as British Customs destroyed the books in the harbor. This is one of approximately seven known copies of the five hundred replacements to survive.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

London: published for the Egoist Press by John Rodker, Paris, 1922 [i.e., 1923]

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2017: PML 196725

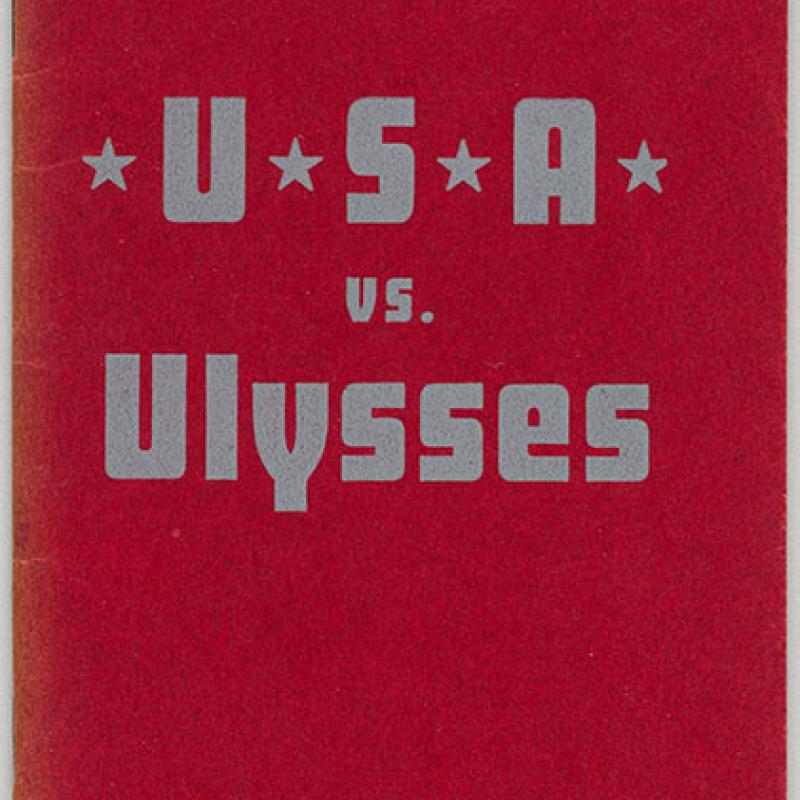

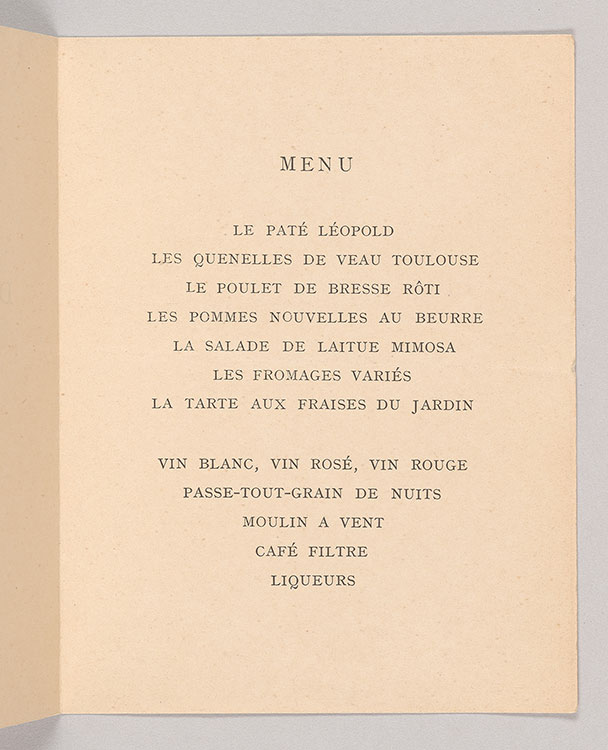

Ulysses in New York

The sensationalism surrounding Ulysses in the media and the absence of international copyright law in the 1920s encouraged “bookleggers” such as Samuel Roth (1893–1974), who serialized the novel in his magazine Two Worlds Monthly without Joyce’s consent. At that time, foreign authors had to publish their work in America in order to secure a US copyright; this was impossible for Joyce, however, since Ulysses was banned. Roth skirted the ban by censoring the text himself, mangling it in the process. With little recourse, Sylvia Beach and Joyce started a petition that called on American readers and media outlets to boycott all of Roth’s ventures. Virginia Woolf, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and André Gide were among the scores of eminent signatories. The statement appeared in newspapers and was issued as a broadside.

In 1928, Joyce and Beach obtained an injunction barring the American from advertising Joyce's name, nothing more. Unrepentant, Roth pirated Joyce's entire novel the following year, issuing the first American edition of Ulysses under the false imprint of “Shakespeare and Company, Paris.” The production was shoddy: a line of type was printed upside-down and the text was corrupt. Hundreds, if not thousands, of copies were distributed through the book trade (Random House inadvertently consulted a copy in 1933 when proofing their text of the first authorized American edition). Roth, who endured several stints in jail for dealing in so-called pornographic books, would later become a significant figure in landmark cases relating to obscenity.

"International Protest" [Statement regarding the piracy of James Joyce’s Ulysses by Samuel Roth]

[Paris: s.n., 1927]

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2017; PML 197710

Detail of page from James Joyce (1882–1941), Ulysses (Paris [i.e., New York]: Shakespeare and Company [i.e., Samuel Roth and Max Roth], 1927 [i.e., 1929])

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197795

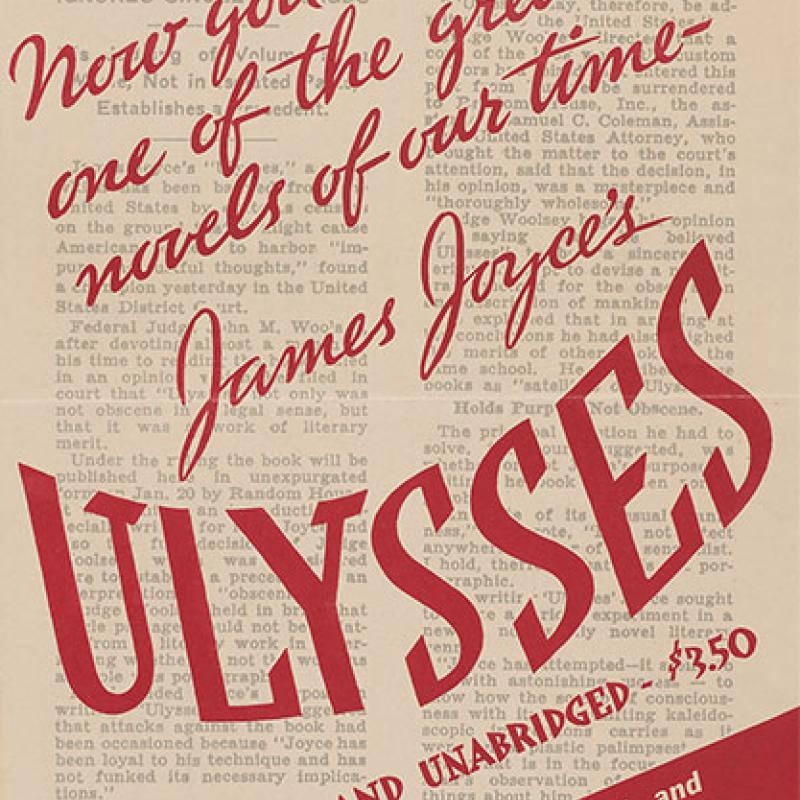

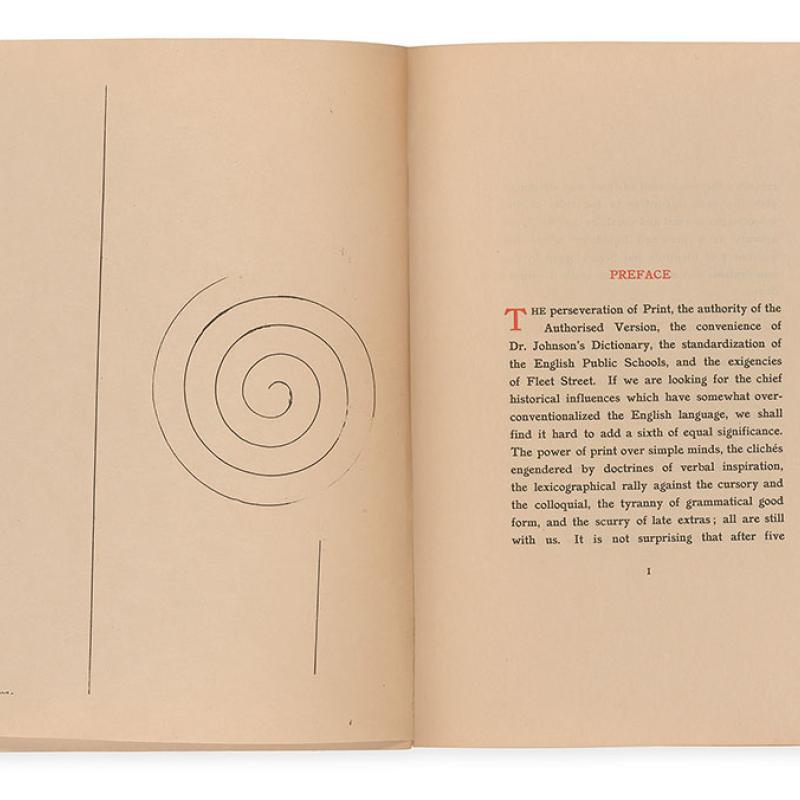

Judge Woolsey's Book Review

When Joyce signed a contract with publisher Bennett Cerf’s Random House in 1932, Ulysses was still illegal in the United Sates. In partnership with ACLU lawyer Morris Ernst, Cerf set out to challenge the ban by importing a copy of Ulysses in plain sight, coaxing the government to put the book on trial. The package entered New York harbor unnoticed and made its way to Cerf’s office, prompting Ernst to return it to US Customs agents and, putting on an act, demand that the “suspicious” package be opened and subsequently seized. Within a few days, Cerf sent a circular letter to “editors, critics, authors, clergymen, members of the bar, sociologists, psychologists, teachers and libraries” to solicit opinions about the novel. Letters received in response became part of a strategic body of documentation, attesting to the book’s artistic value. In court Ernst argued for the novel’s literary merits. Judge John Munro Woolsey’s 1933 decision agreed that Ulysses was “a sincere and serious attempt to devise a new literary method for the observation and description of mankind”—its allegedly obscene passages more likely to nauseate than sexually arouse. Woolsey’s friends printed his opinion in this pamphlet as the “latest . . . book review by Judge Woolsey.”

United States District Court (New York: Southern District)

United States of America, Libelant vs. One Book Called “Ulysses”

Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1935

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197837

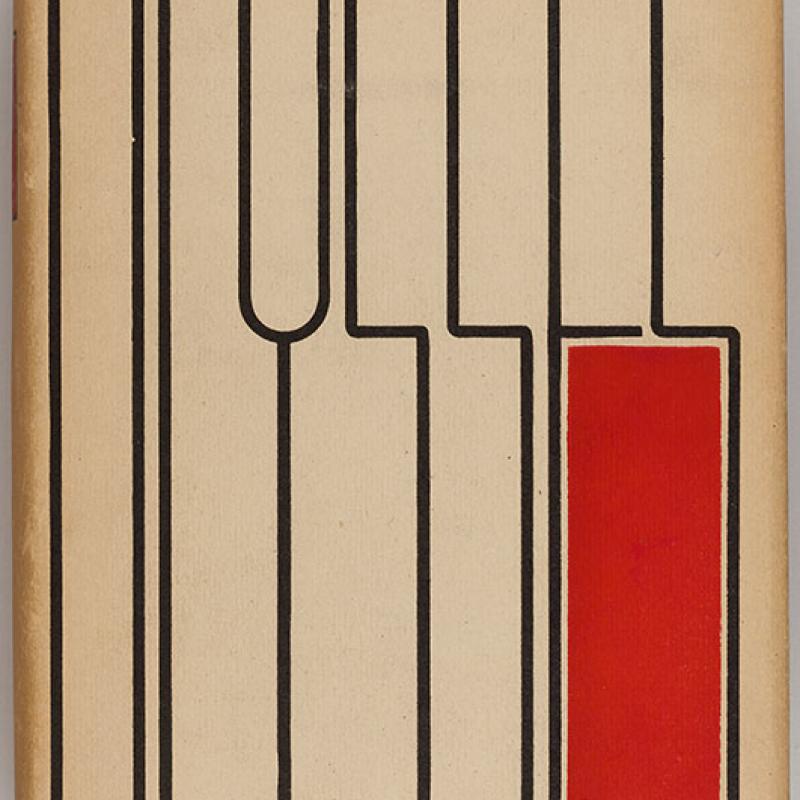

The Random House Edition

Moments after Judge Woolsey’s 6 December 1933 ruling, word was handed down to Random House’s typesetters to begin printing. Ulysses was published in America on 25 January 1934 in an edition of around ten thousand. The novel’s backstory and Bennett Cerf’s marketing strategies had all but guaranteed a smash hit. By 1939 over fifty thousand copies had been sold. Woolsey’s legal decision was printed at the front of the book, and Joyce contributed a letter about its publication history in place of an introduction.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Book design by Ernst Reichl (1900–1980)

New York: Random House, 1934

The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135629

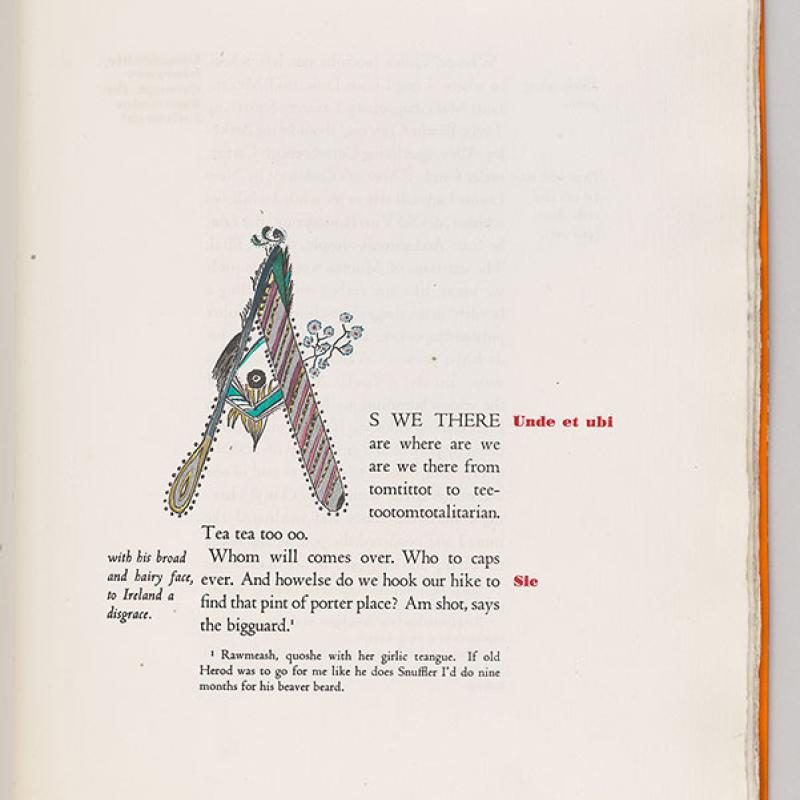

Ernst Reichl

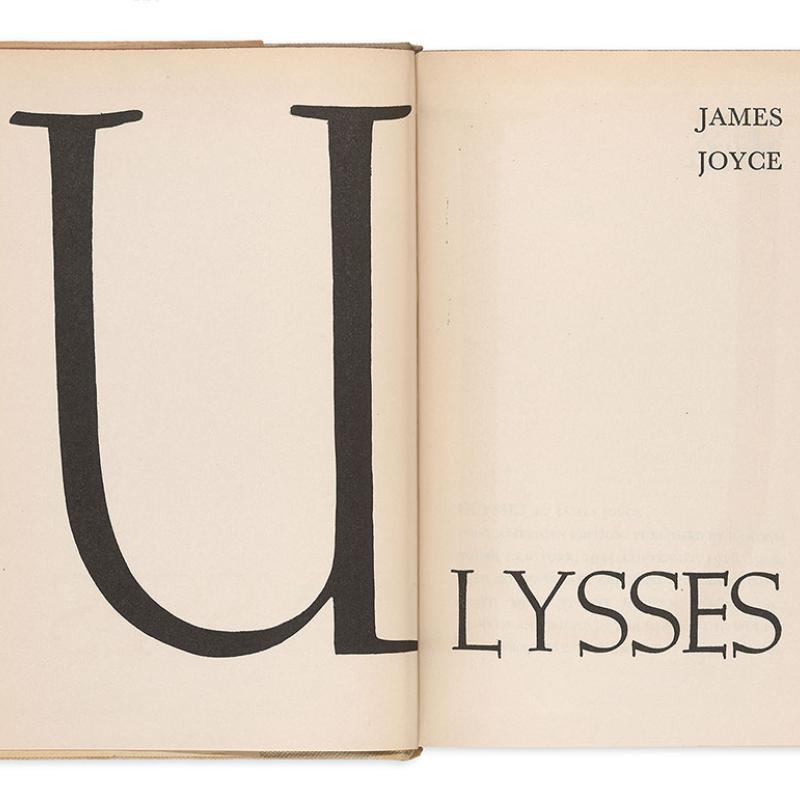

Ernst Reichl, the lead designer at H. Wolff, which manufactured the Random House edition, combined his own elongated lettering on the dust jacket with eighteenth-century Baskerville inside and slightly altered versions of Ernst Rodolf Weiss's brand-new capitals. His innovative work achieved a modern aesthetic that simultaneously evoked the full-page ornate initials associated with medieval page design. Reichl had already won an AIGA award for a book with a double-page title spread, though the lettering had appeared only on the recto. For the double-spread title of Ulysses, however, a large U stands alone on the facing page, serving both as text and image. It became a landmark of modern graphic design.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Book design by Ernst Reichl (1900–1980)

New York: Random House, 1934

The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135629

Now You Can Read Ulysses

Now You Can Read One of the Great Novels of Our Time—James Joyce’s “Ulysses”

New York: Random House, [1934]

Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

Reactions

Unknown photographer

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and Company, ca. 1926

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

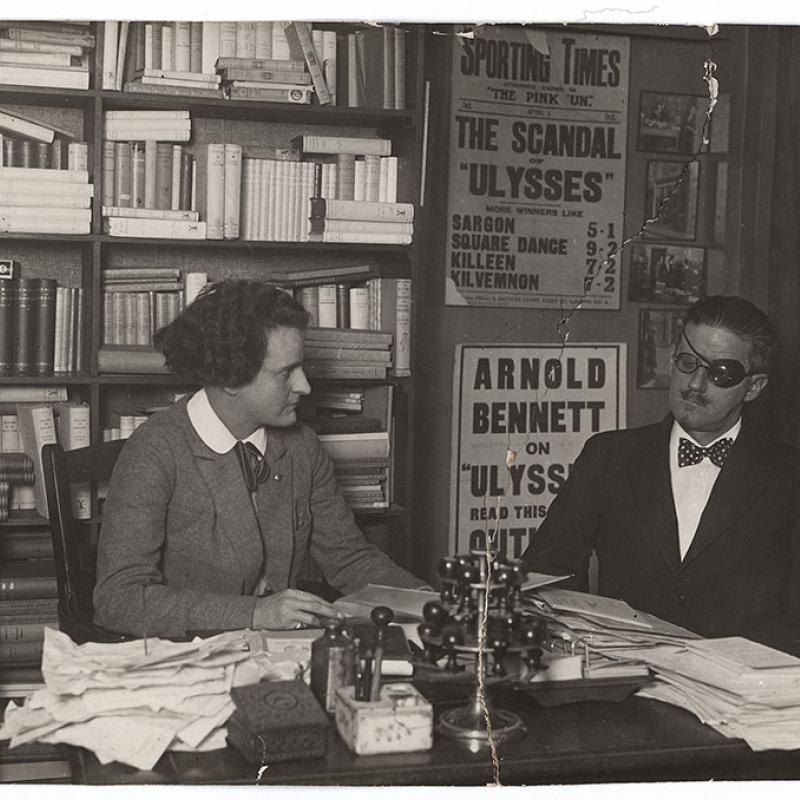

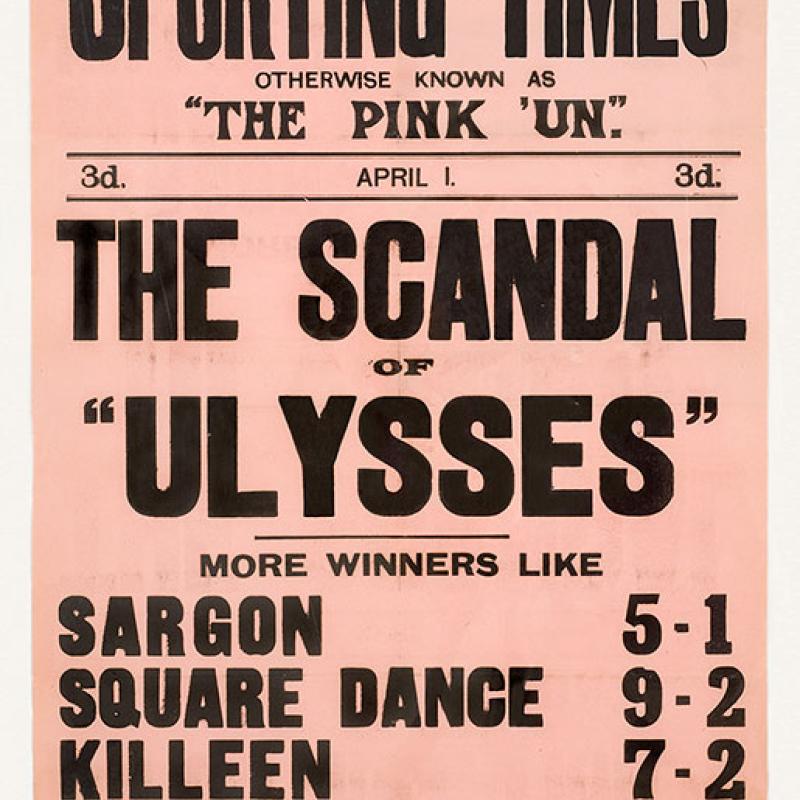

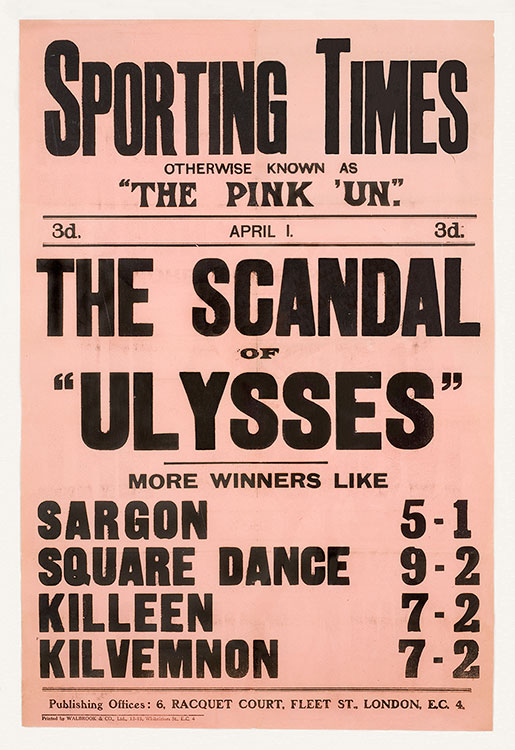

The Scandal of Ulysses

Sylvia Beach and Harriet Shaw Weaver both collected clippings on Joyce’s behalf. After noticing the “Scandal” screamer in the Sporting Times, a London weekly, Weaver obtained copies of placards advertising the issue and sent at least two to Paris for Joyce and Beach. The Sporting Times write-up emphasized the book’s scabrous qualities, calling it a “stupid glorification of mere filth” and “literature of the latrine”; but the word “scandal” referred equally to the reviewer’s verdict of tediousness. Joyce chose one of the writer's sentences calling Ulysses “intensely dull” for Weaver's leaflet of press notices promoting the novel. Beach displayed another copy of this placard in her shop for years.

Placard for the Sporting Times, 1 April 1922

[London: Walbrook & Co., 1922]

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

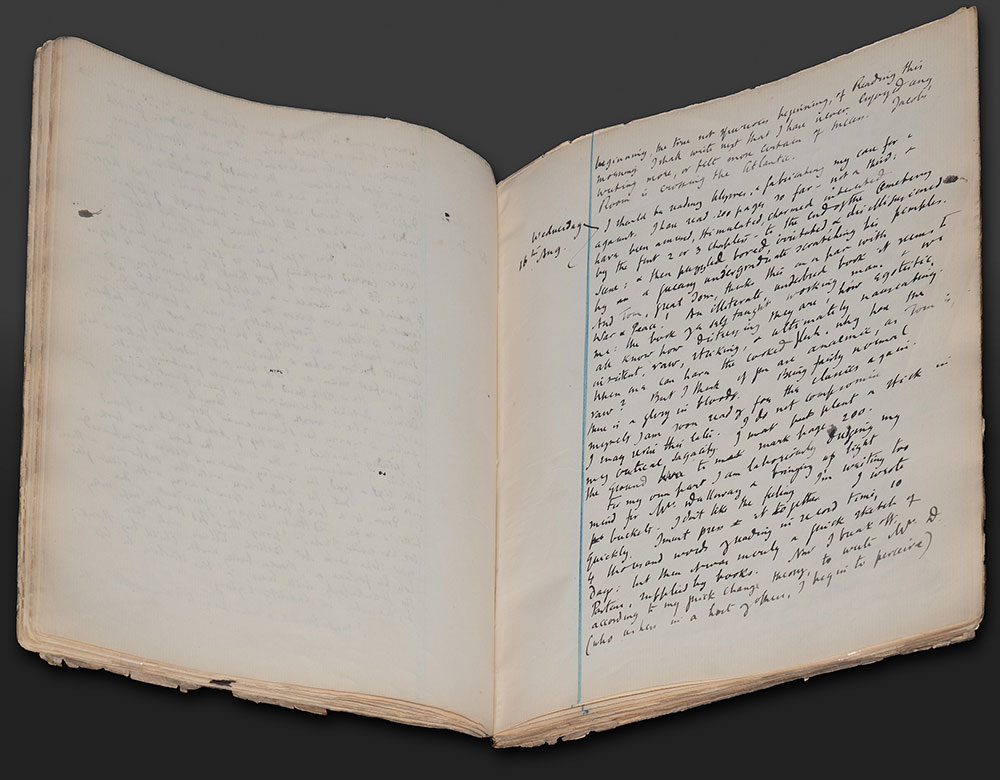

Virginia Woolf Responds

Virginia Woolf’s diary entry, which begins,“I should be reading ‘Ulysses’ and fabricating my case for and against,” conveys a mix of emotions and opinions about the novel’s first two hundred pages. Stimulated and amused by early episodes, Woolf is ultimately repulsed by its graphic passages. Shocked that “great Tom” (T. S. Eliot) rates it on a par with Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Woolf calls Ulysses an “underbred” novel by an egoistic “self-taught working man.” Elsewhere in her diary and writings, Woolf sets aside some of her condescension and recognizes that Joyce was rehearsing aspects of narrative that she herself had begun to articulate and would realize in her own way: “to record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall,” “an ordinary mind on an ordinary day.”

Installation shot of Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), Diary entry, 16 August 1922

The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf

Ulysses, when it appeared, created a great stir. Figures like T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats praised the book highly, but there were others who viewed it much more suspiciously, including Virginia Woolf. Her diary entry on the book begins,“I should be reading Ulysses and fabricating my case for and against.” And she was stimulated and amused by an early episode, but eventually, she was shocked by its graphic passages. She called Ulysses “Underbred novel, by an egotistical, self taught working man,” which James Joyce certainly wasn't. But elsewhere, she did set aside some of her condescension and she did recognize that Joyce was rehearsing aspects of narrative, that indeed she herself was working with, “To record,” as she said, “the atoms as they fall upon the mind, the order in which they fall, an ordinary mind on an ordinary day.”

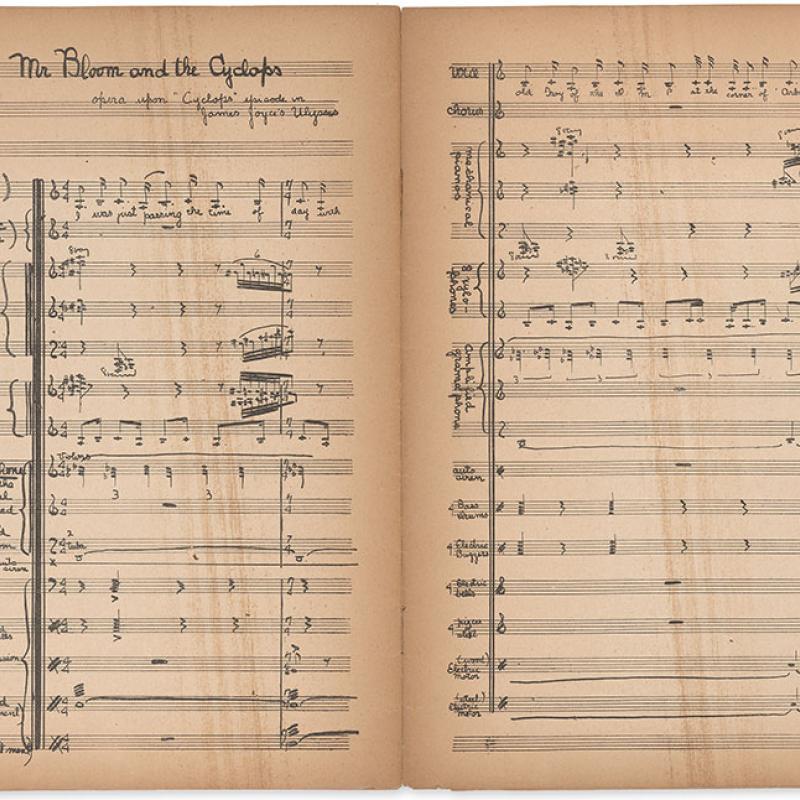

George Antheil

In early 1924 the Chicago Tribune heralded a new “electric opera” based on Ulysses by the modern composer George Antheil (1900–1959). The classically-trained New Jersey native was then living in Paris above Shakespeare and Company. Joyce and Nora became fond of the young avant-garde musician. They attended several of Antheil's riotous Paris concerts and remained friends for years. Despite his conservative taste in music, Joyce encouraged Antheil to complete the experimental work based on the "Cyclops" episode, giving him one of the coveted copies of the Ulysses Schema to aid in his endeavor.

Despite the advance publicity, Antheil never finished "Mr Bloom and the Cyclops." Instead, he became famous for the piece he was composing simultaneously: Ballet mécanique, with its player pianos, amplifiers, sirens, and standing fans simulating airplane propellers. As indicated on the fragment of the “Cyclops” score published in 1925, his Ulysses opera was arranged for electric motors, buzzers, amplified voices, gramophones, and sixteen player pianos. Subsequent collaborations between Joyce and Antheil also came to naught, though Antheil later published a musical setting of Joyce's poem "Nightpiece."

George Antheil (1900–1959)

“Mr Bloom and the Cyclops”

This Quarter 1, no. 2, Musical Supplement (October 1925)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Annette de la Renta in memory of Carter Burden, 2005; PML 129675

Unknown Photographer

Sylvia Beach and George Antheil Climbing Up to His Apartment, ca. 1923

Private collection

© Estate of Peter Antheil

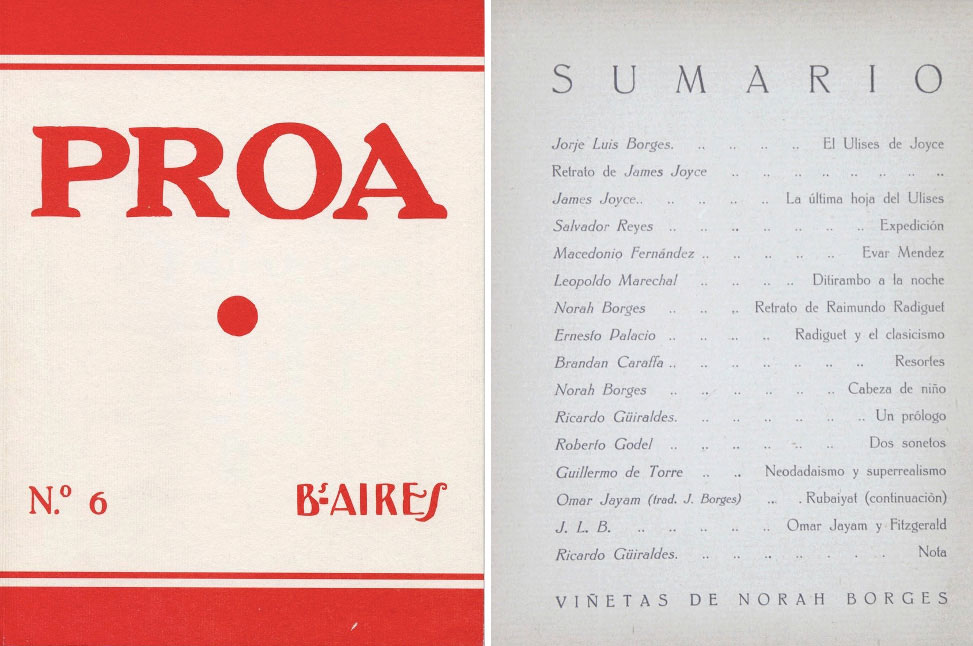

Jorge Luis Borges

Borges refers to himself in a 1925 review of Ulysses on display as the first Hispanic adventurer to have reached the novel’s untamed country. The piece appears in an issue of Proa along with Borges's loose translation of the last passage of "Penelope." A letter from Borges to Guillermo de Torre and their shared copy of Ulysses, both in the Morgan's collection, document ways in which Joyce's work resonated for avant-garde writers in Argentina attempting to distinguish their work and their language from Spanish literature. Throughout his life, Borges would praise Joyce’s relation to time, merging of dream and waking, and creation of a total reality. But Borges also characterized Ulysses almost as a monstrosity, a text so expansive and elaborate that it was impossible to read or understand in its entirety. Borges’s own masterly short fiction often centers on themes suggestive of Joyce’s encyclopedic approach to creating Ulysses. Scholars have also noted that several of Borges’s characters are portrayed as Ulysses’ ideal readers—figures with infinite memories, such as Ireneo Funes, whom Borges mentioned in his 1941 obituary for Joyce.

Cover and table of contents for Proa, no. 6 (January 1925)

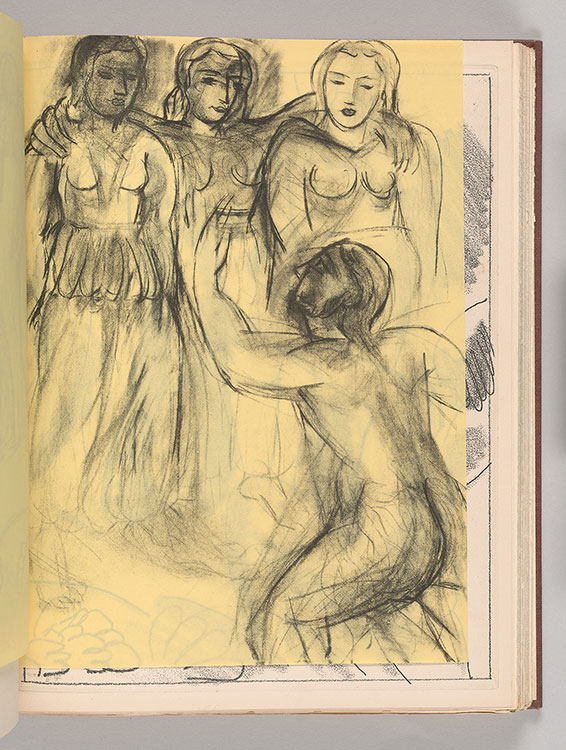

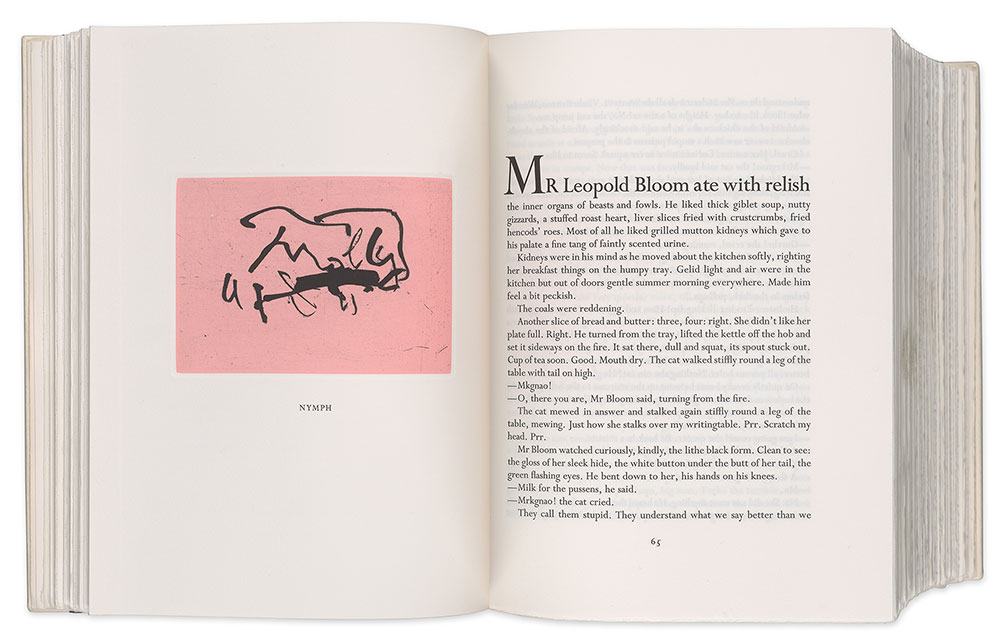

Henri Matisse

The French painter Henri Matisse depicted figures related to the novel’s Homeric allusions for a deluxe edition of Ulysses in 1935. He was not adept at reading English and gave up on tackling the monumental novel in translation. As an alternative, a friend loaned him a book-length study of the novel by Stuart Gilbert. Writing under Joyce’s supervision, Gilbert had emphasized the work’s correspondences to classical literature. The artist was also given a copy of the Random House circular How to Enjoy James Joyce’s “Ulysses”, which made use of Joyce's Schema. When the edition’s publisher, George Macy, was unable to see connections between Matisse’s first two prints and the novel, the painter curtly relayed through his son that Random House had explicitly stated,“Nausicaa = Gerty MacDowel” [sic]. Joyce consented to Matisse’s approach over the telephone, the sole direct contact that transpired between artist and author.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses. Illustrated by Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

New York: Limited Editions Club, 1935

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197805

Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

Preparatory drawing for Ulysses [the “Nausicaa” episode], 1934 Red chalk

The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation

© 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York [permission not yet granted]

Vladimir Nabokov

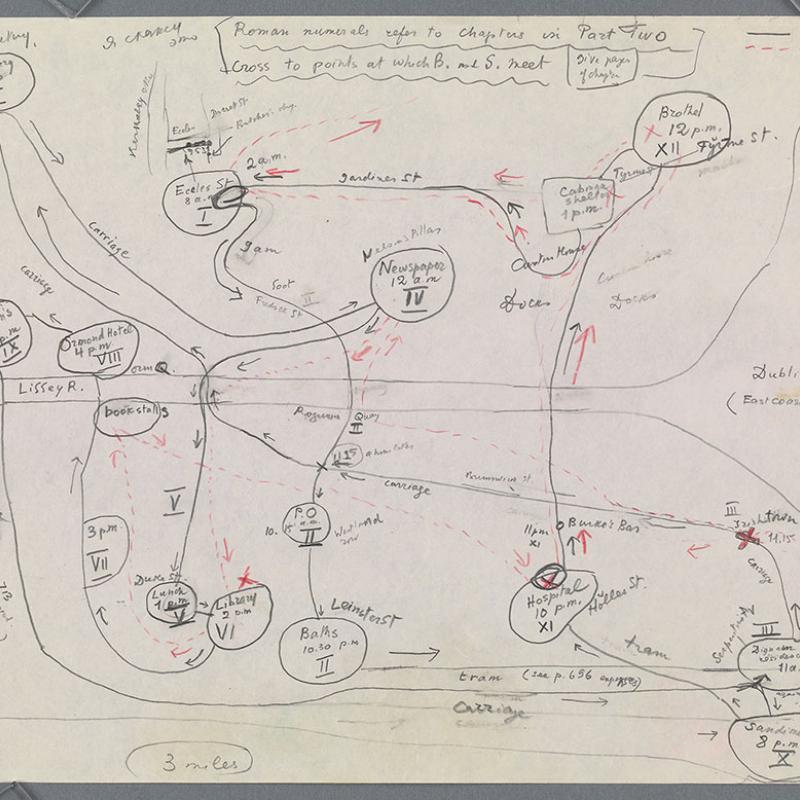

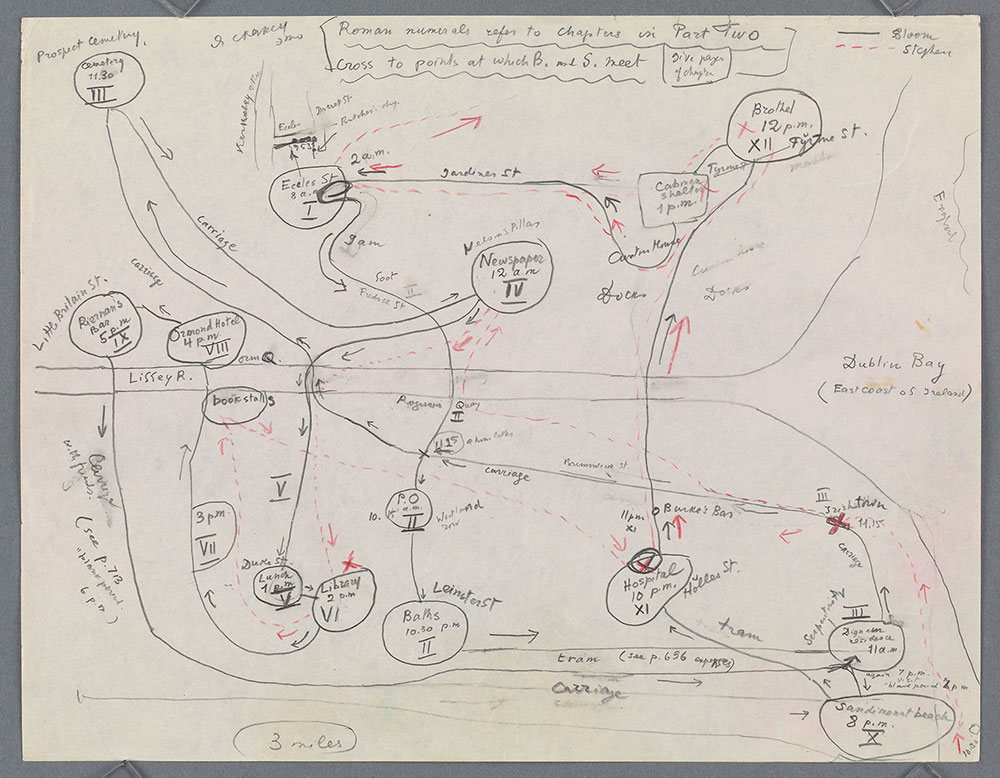

Nabokov drew this diagram, which maps the itineraries of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus in twelve episodes, for a course he taught called Masters of European Fiction. The Russian American novelist described these classes as “a kind of detective investigation of the mystery of literary structures.” He encouraged his pupils to approach artworks as entirely new worlds, study them closely in and of themselves, and “fondle the details.” In his notes for Ulysses, Nabokov draws attention to the novel’s synchronicities as exemplary of Joyce’s supreme artistic control—pointing out the near misses and intersections of Bloom and Stephen (“a kind of slow dance of fate”) and of language, gesture, and thought—“Everything is in correspondence.”

Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977)

Map of Leopold Bloom’s and Stephen Dedalus’s travels through Dublin, ca. 1948–58

Graphite and colored pencil

The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

© Vladimir Nabokov, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC

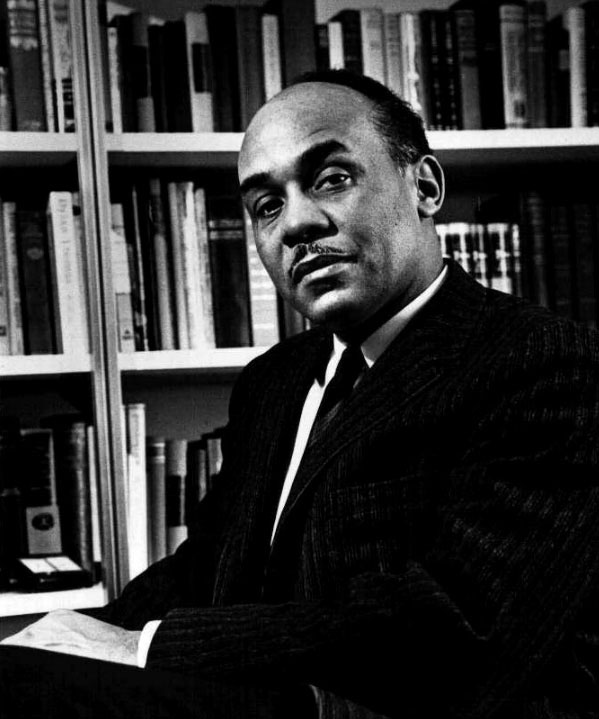

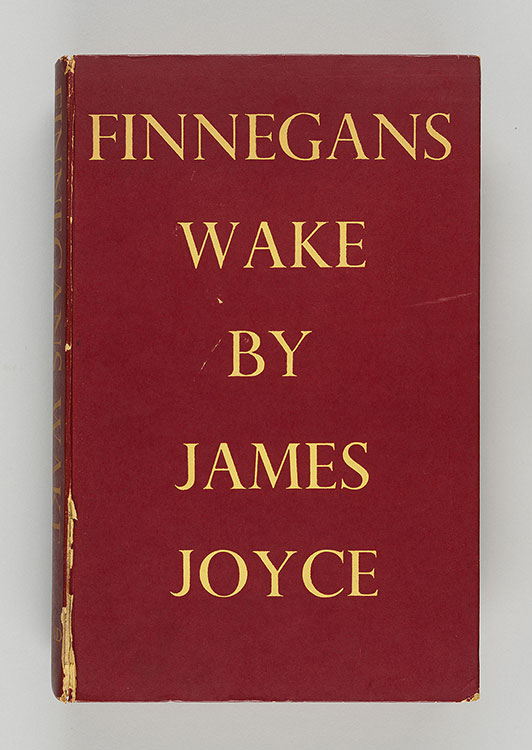

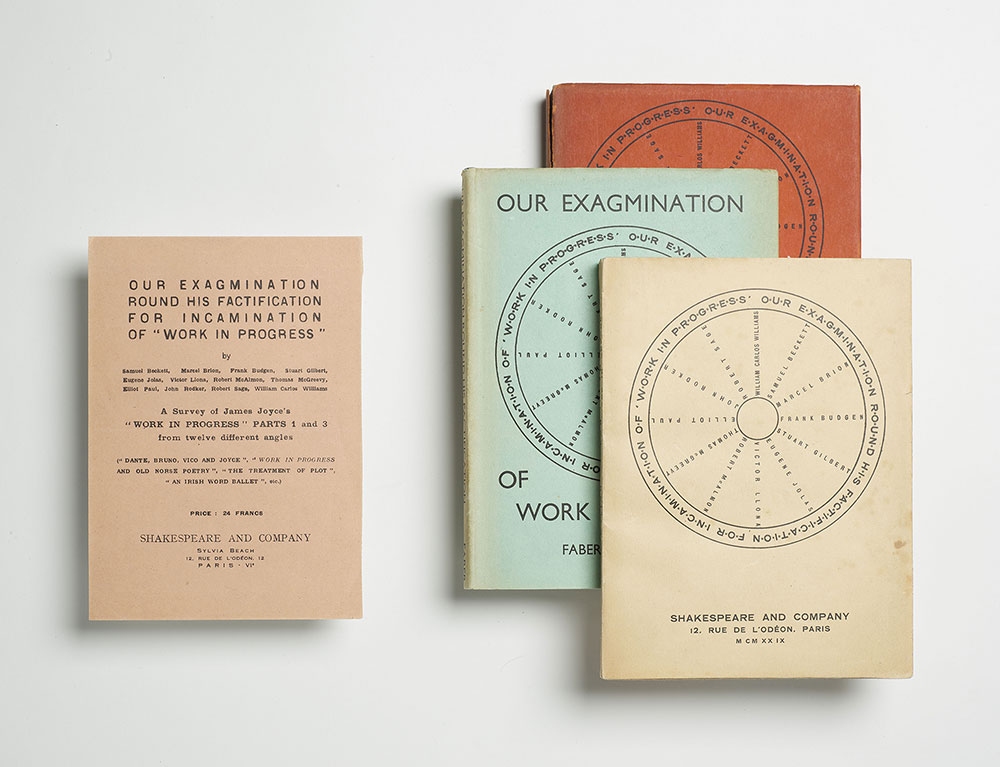

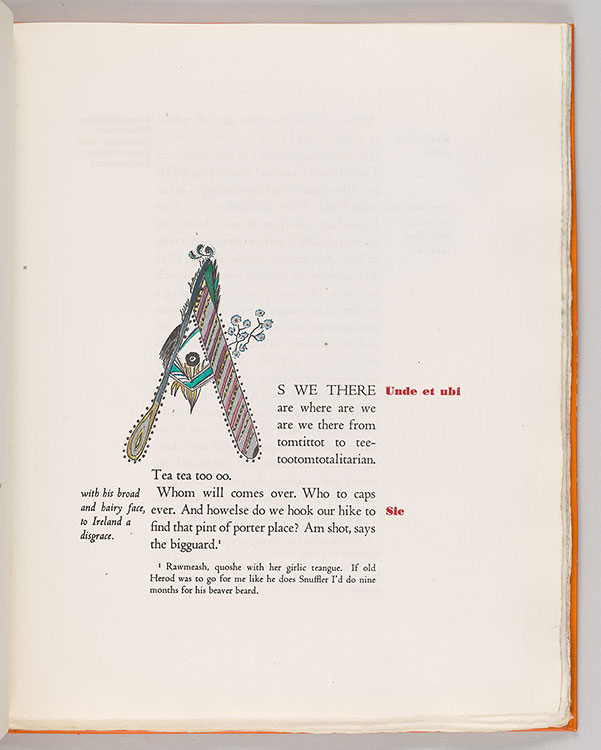

Ralph Ellison